Michigan-Henderson-Liu-1NC-UNLV

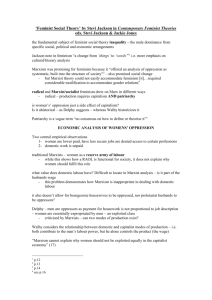

advertisement