Brief Introduction PowerPoint

advertisement

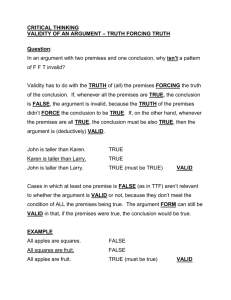

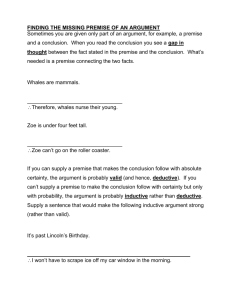

A Brief Introduction to Logic Logic is… • The study of argument • The study of criteria for distinguishing successful from unsuccessful arguments and the study of methods for applying those criteria • An argument is a set of statements, some of which—the premises—are supposed to support, or give reasons for, the remaining statement—the conclusion • In a successful argument the premises genuinely support the conclusion • ‘genuine support’ requires the probable or guaranteed preservation of truth from premises to conclusion • The study of related properties such as consistency, logical truth, etc. • The key to a world of wonder Logic is not… • Logic is not the study of persuasion and manipulative rhetorical devices • ‘successful argument’ does not mean persuasive argument – Human fallibility and manipulative rhetoric lead people to • accept poor reasoning • reject good reasoning • Remember, in a successful argument if the premises are true, then the conclusion is either guaranteed to be true or likely to be true Why Study Logic? • Intrinsic value – Enjoyment of learning – Enjoyment of abstract structures and analytic elegance – Enjoyment of puzzles and figuring things out • Instrumental value – Improve abstract, critical, and analytic reasoning – Increase the number of tools in your critical thinking “toolkit” – Improve writing, reading, speaking skills – Become a better thinker/knower – Become a more independent thinker – Become the life of the party Some Definitions: Statement: A statement is a declarative sentence; a sentence which attempts to state a fact—as opposed to a question, command, exclamation, etc. Argument: an argument is a (finite) set of statements, some of which—the premises— are supposed to support, or give reasons for, the remaining statement—the conclusion Logic: Logic is the study of (i) criteria for distinguishing successful from unsuccessful argument, (ii) methods for applying those criteria, and (iii) related properties of statements such as implication, equivalence, logical truth, consistency, etc. Truth Value: The truth value of a statement is just its truth or falsehood; we assume that every statement has either the truth value true, or the truth value false, but not both An Example Argument • Socrates is mortal, for all humans are mortal, and Socrates is human • Given that Socrates is human, Socrates is mortal; since all humans are mortal • All Humans are mortal, Socrates is human; therefore Socrates is mortal Premise and Conclusion Indicators Premise Indicators: as, since, for, because, given that, for the reason that, inasmuch as Conclusion Indicators: therefore, hence, thus, so, we may infer, consequently, it follows that Standard Form Premise 1 Premise 2 Premise n Conclusion All humans are mortal Socrates is human Socrates is mortal Argument Form and Instance Argument Form and Instance: An argument form (or schema) is the framework of an argument which results when certain portions of the component sentences are replaced by blanks, schematic letters, or other symbols. An argument instance is what results when the blanks in a form are appropriately filled in Form and Instance Form: All F are G x is F x is G Instances: All humans are mortal Socrates is human Socrates is mortal All monsters are furry Grover is a monster Grover is furry Two Types of Criteria for Successful Arguments • Deductive • Inductive – These criteria have some things in common, but will turn out to be importantly different – The distinction is NOT • Deductive = general to specific • Inductive = specific to general – THE ABOVE IS INCORRECT – The distinction will involve the nature of the link between premises and conclusion – This is best illustrated… Argument 1A All whales are mammals All mammals are air-breathers All whales are air-breathers “Good” or “Bad”? T T T All Premises True Conclusion True F1 G1 Argument 1B All whales are fish All fish are air-breathers All whales are air-breathers “Good” or “Bad”? F F T At least One Premise False Conclusion True F1 G1 Argument 1D All whales are reptiles All reptiles are birds All whales are birds “Good” or “Bad”? F F F At least One Premise False Conclusion False F1 G1 Form 1 All F are G All G are H All F are H F2 G1 Conclusion False Conclusion True All premises True At least one premise False 1A 1B All whales are mammals All mammals are air-breathers All whales are air-breathers All whales are fish All fish are air-breathers All whales are air-breathers 1C 1D ?????? All whales are reptiles All reptiles are birds All whales are birds F1 G2 Argument 2A Some animals are frogs Some animals are tree-climbers Some frogs are tree-climbers “Good” or “Bad”? T T T All Premises True Conclusion True F2 G2 Argument 2B Some fish are frogs Some fish are tree-climbers Some frogs are tree-climbers “Good” or “Bad”? F F T At least One Premise False Conclusion True F2 G2 Argument 2D Some fish are frogs Some fish are birds Some frogs are birds “Good” or “Bad”? F F F At least One Premise False Conclusion False F2 G2 Argument 2C Some animals are frogs Some animals are birds Some frogs are birds “Good” or “Bad”? T T F All Premises are True Conclusion False F2 G2 Form 2 Some F are G Some F are H Some G are H F1 G2 Conclusion False Conclusion True All premises True At least one premise False 2A 2B Some animals are frogs Some frogs are tree-climbers Some fish are frogs Some fish are tree-climbers Some frogs are tree-climbers 2C 2D Some animals are frogs Some animals are birds Some frogs are birds Some fish are frogs Some fish are birds Some frogs are birds Some animals are tree-climbers F2 G1 Evaluating Deductive Arguments Deductive Validity, Invalidity: An argument (form) is deductively valid iff* it is NOT possible for ALL the premises to be true AND the conclusion false, it is deductively invalid iff it is not valid Soundness: An argument is sound iff it is deductively valid AND all its premises are true * ‘iff’ is short for ‘if and only if’ Conclusion False Conclusion True All premises True At least one premise False 1A 1B All whales are mammals All mammals are air-breathers All whales are air-breathers All whales are fish All fish are air-breathers All whales are air-breathers Valid & Sound Valid but Unsound 1C 1D No Possible Instance (No possible counterexample) All whales are reptiles All reptiles are birds All whales are birds Valid but Unsound F1 G2 Conclusion False Conclusion True All premises True At least one premise False 2A 2B Some animals are frogs Some animals are tree-climbers Some frogs are tree-climbers Some fish are frogs Some fish are tree-climbers Some frogs are tree-climbers Invalid Invalid 2C 2D Some animals are frogs Some animals are birds Some frogs are birds Some fish are frogs Some fish are birds Some frogs are birds Invalid Invalid (Counterexample to Form 2) F2 G1 Argument Forms 1 & 2 Form 1 Form 2 All F are G All G are H All F are H Some F are G Some F are H Some G are H Valid Form Invalid Form Some Points about Validity • Validity a question of Truth Preservation • It is a matter of Form – Thus an argument form is valid (invalid), and any instance of that form is valid (invalid) • It has nothing to do with actual truth values of the sentences involved* – True premises and true conclusion are neither necessary nor sufficient for validity (see 1B, 1D, and 2A) *Except for counterexamples… Counterexamples and Invalidity Counterexample: A counterexample to an argument (form) is an instance of exactly the same form having all true premises and a false conclusion. Production of a counterexample shows that the argument form and all instances thereof are invalid. – This is the ONLY time actual truth values are relevant • If all premises are true and the conclusion is false, that instance, that form, and any other instance of that form are invalid Counterexamples and Invalidity • We can see that a particular argument, an argument form, and all instances of that form are invalid by either: – Offering a counterexample, or – Consistently imagining that all the premises are true and the conclusion is false • Failure to do one of the above shows nothing, however, because it may be just our lack of creativity which prevents us finding a counterexample or imagining the appropriate situation Soundness • An argument is sound iff it is deductively valid and all the premises are true • Unlike validity, soundness does have to do with the actual truth values of the premises • Soundness is only an issue when the argument is valid • Unsound arguments will not convince a worthy opponent • Determining soundness is outside the bounds of logic, it requires non-logical investigation Evaluating Deductive Arguments Invalid but still “good”? There are 4 Jacks in this standard deck of 52 cards The deck has been shuffled The next card drawn will not be a Jack Most Rottweilers have docked tails Ralphie is a Rottweiler Ralphie has a docked tail Evaluating Inductive Arguments Inductive Strength: An argument is inductively strong to the degree to which the premises provide evidence to make the truth of the conclusion plausible or probable. If an argument is not strong, it is weak. Cogency: An argument is cogent iff it is inductively strong AND all the premises are true Induction by Enumeration A1 is F A2 is F An is F All As (or the next A) are/will be F All 57 trout caught in Jacob’s Creek were infected with the RGH virus All trout (or the next trout caught; or x% of trout) in Jacob’s Creek will be infected with the RGH virus • The As are the sample—the observed instances or examples; • F is the target property Argument by Analogy A is F, G, H B is F, G, H, and I A is I My car is a 1999 Toyota Camry Sue’s car is a 1999 Toyota Camry and gets over 30 mpg My car will get over 30 mpg • F, G, H are the similarities, I is the target property • The comparison base, B, may be an individual or a group Some Rules of Thumb for Enumerations/Analogies • The larger the sample size or comparison base group, the stronger the argument • The narrower or more conservative the conclusion, the stronger the argument • The greater the number of (relevant) similarities, the stronger the argument • The fewer the number of (relevant) dissimilarities, the stronger the argument Inductive Strength Not a Matter of Form The 12,700 days since my birth have all been days on which I did not die So I will not die today. Indeed, I’ll never die! I like peanuts, am bigger than a breadbox, and have two ears Bingo the elephant likes peanuts, is bigger than a breadbox, has two ears, and has a trunk I have a trunk Validity vs. Strength • Unlike deductive validity, inductive strength is a matter of degree, not an all-or-nothing, on/off switch • Unlike deductive validity, inductive strength is not a matter of form • Unlike deductive validity, additional information is relevant to the assessment of strength Background Knowledge & Strength • Determining strength of an inductive argument has a lot to do with many unstated background assumptions, e.g.: – Relevance of similarities and dissimilarities – Nature and selection of the sample group – Stability of relevant but unstated conditions • It also has to do with the availability of further evidence, thus • Unlike with validity, additional premises (new evidence, change in background assumptions) can increase or decrease the strength of the argument Abduction Abduction: Abduction or abductive reasoning, also known as inference to the best explanation is a category of reasoning subject to inductive criteria in which the conclusion is supposed to explain the premises Examples It is 5pm on Monday The mail has not come The mail carrier is almost never late It must be a holiday I see paw prints on the hood and roof of my car There are fur balls in the corner There are mice guts under the car The garage door was left open The cat slept in the garage About Abduction • The more data accounted for the better the explanation • The better the explanation coheres with already confirmed theory, the better it is • The more new data successfully predicted, the better the explanation • So, again, background assumptions are relevant • There is almost always more evidence available, and it might lead to a reassessment of the inference/argument • Exactly what is meant by “best” is not entirely clear Evaluating Inductive Arguments Fallacies Fallacy: A fallacy is any mistake in reasoning, but some are particularly seductive (both to the speaker/writer and the listener/reader) and so common that they have earned names. See the text for details… Carroll and Tenniel Charles Lutwidge Dodgson [1832-1898] Known by his pen name, Lewis Carroll, Dodgson was a man of diverse interests—in mathematics, logic, photography, art, theater, religion, medicine, and science. He was happiest in the company of children for whom he created puzzles, clever games, and charming letters. His book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), became an immediate success and has since been translated into more than eighty languages. The equally popular sequel Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There was published in 1872. The “Alice” books are but one example of his wide ranging authorship. The Hunting of the Snark, a classic nonsense epic (1876) and Euclid and His Modern Rivals, a rare example of humorous work concerning mathematics, still entice and intrigue today's students. Sylvie and Bruno (1889), published toward the end of his life, contains startling ideas including a description of weightlessness. Adapted from: http://www.lewiscarroll.org/cld.html Sir John Tenniel [1820–1914] English illustrator and satirical artist, especially known for his work in Punch and his illustrations for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the LookingGlass (1872). In his drawings for Punch Tenniel lent new dignity to the political cartoon. Tenniel was knighted in 1893 and retired from Punch in 1901. He illustrated many books; his drawings for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass are remarkably subtle and clever and are extremely well-suited to Lewis Carroll's text. These illustrations won him an international reputation and a continuing audience. Excerpted from: http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9071700