Required reading - Harvard Kennedy School

advertisement

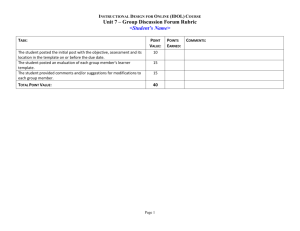

IGA 385: Strategizing for Human Rights: Moving from Ideals to Practice Fall 2015 DRAFT Instructor: Douglas A. Johnson Office: Rubenstein 214 Telephone: 617-495-8299 Email: douglas_johnson@hks.harvard.edu Office hours: Thursday 3:00 – 5:30 pm Faculty Assistant: Derya Honça Office: Rubenstein 215 Telephone: 617-495-1923 Email: derya_honca@hks.harvard.edu Time and Location: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 1:15 pm-2:30 pm, BL-1 Course Description: Violence and social injustices abound in the world. How do we make a difference? This class will apply the concepts of strategizing to today’s human rights struggles, examining cases of successful efforts to learn key principles and applying them to live and unsettled cases Over the last decades, the human rights movement has emphasized the development of international treaties to define ideals as legal norms, created international institutions and instruments to encourage those norms to be implemented, and built local, national, and transnational civil society organizations to bring attention to the gap between norms and reality. Yet many believe that the global situation is getting worse, not better, and that we have 1 reached “the end times of human rights.” Committing our professional futures to human rights struggle requires not only moral commitment but also the sense that we are being effective and strategic in our approaches to change making. We will study how to think strategically and apply that thinking to cases that are still active arenas of conflict over ideals of justice and the realities of power imbalance, where the risks of failure are both present and of serious consequence. We will explore social science research that is useful to the leadership task of strategizing, broaden our understanding of available tactics, use tactical mapping and other strategizing tools to construct alternative scenarios to resolve an active human rights struggle, and apply analytic frameworks that help us think through the acceptable balance between risk and success in making social change. Speaking at the Harvard Kennedy School in 2014, Michael Posner (former President of Human Rights First and Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Rights, and Labor) declared that the “human rights’ movements inability to strategize effectively has reached crisis proportions.” This class is intended to draw on the experience of HKS students, faculty, and guest speakers to improve our capacities to think and act strategically. Social science research can shed light on the strategic choices leaders must make. Some of this research tackles big questions: Why do human rights violations occur and what can be done to prevent them? What difference do human rights treaties make for changing state practices? Some research relates to more tactical qustions: How can governments, international organizations, and human rights NGOs contribute to bringing about positive human rights change? This class will integrate reading, discussion, and class projects relevant to the effective practice of human rights to try to answer these questions and others. We will examine political, economic, psychological and ideological explanations for human rights violations, and theories of state commitment and compliance with human rights norms and treaties. We will also explore the role of governments, international organizations and civil society organizations in the promotion and protection of human rights. Each theoretical discussion will also ask students to address how research findings could influence choices of practitioners about tools to promote human rights. The course will also focus on building strategic capacity through group projects addressing a human rights issue of interest to the students, using the tactical mapping technique and searching tactical databases to understand what governments and NGOs around the world are doing or could be doing to enhance compliance with human rights norms. Learning Outcomes: To expand understanding of strategy and how to develop effective strategy and tactics to address human rights issues. To acquaint practitioners with social science research that may affect strategic choices for intervention. To explore the major methods governments, international organizations and civil society organizations use to promote human rights and prevent violations. Expectations and Evaluation: 2 This is a graduate-level course and will have the associated standards and assignments: complete attendance at scheduled classes, assignments completed on time, and evaluation according to students’ class participation and quality of written assignments. Final grades will be based on the following percentages: 10% Course participation. 10% Team case presentations in class. 30% Short case memos (500 words). 10% Written feedback to peers 40% for the Final Policy Memo (divided up as follows) 30% for the final memo 5% for one page draft of the topic of the paper 5% for one page description of strategy and tactics Class Participation: You are expected to come to each session prepared to discuss the day’s assignment, readings and cases, and to make thoughtful contributions to the learning of your classmates. Class participation points will include attendance and engagement in the class sessions. The expectation is that students will attend all class sessions. Each student is expected to participate in a team to open discussion and analysis of two (2) strategic case studies. Each session will comprise up to 5% of the course. Methods of teaming up and preparation expectations will be handed out in class prior to the first case presentation. (See also the short assignments on writing case presentations below.) Leadership of a case presentation should be done on a case NOT selected for the writing assignment. Study Groups: You will be assigned to a working group of four to five students. Each study group will do inclass group work together and work together to discuss and develop their ideas for assignments. Groups will be randomly assigned and will sit together each class day to facilitate small group work. Writing Assignments: Leaders of human rights organizations indicate that one of the most valuable skills they look for in staff is the ability to write clearly and well in a number of formats. Consequently, writing assignments constitute the majority of points that determine grades for this class. In addition to feedback from the professor, students will also receive and give structured feedback to one another on the power of the argument and the writing style with the aim of improving both skills. A paper copy of each assignment should be brought to class to share with another student. 1. Three Short Case Papers (500 words): During the semester, you will prepare and submit three 500-word case papers. You will find the case paper opportunities listed on the Course Assignment Calendar on the course page and 3 should upload your case papers there. The dates for which you may submit a case paper are as follows: The Landmine Convention: September 15 Female Genital Cutting: September 23 Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos, Peru: September 30 Bonded Labor in India, October 16 Otpor! The Serbian student campaign: October 28 The Treatment Action Campaign, November 6 Blood diamonds: November 20 Each case paper will account for 10% of your grade (for a total of 30%). Paper copies are due at the beginning of class on the day the case is being discussed; an electronic version should also be posted on the website. Since one of the purposes of the case paper is to promote informed discussion of the case, we will not accept any late case papers. Because you will have multiple case opportunities in which to submit a paper, if some emergency arises, you can submit a case paper on another topic at a later date. You are encouraged to discuss your paper with members of your study group, but the writing of the paper must be entirely your own work. 2. Final Take-Home Policy Memo: (2500 words maximum, 12 pt font, double-spaced) Imagine you are an intern this summer at a non-governmental human rights organization, an international organization devoted to human rights or a government human rights bureau of your choice. Your supervisors know you have just completed a course on strategizing for human rights at the Harvard Kennedy School. They ask you to prepare a policy memo for them proposing a new human rights project on an issue you recommend that the NGO, IO, or government bureau should undertake. Your supervisor asks you to draw not only on your knowledge of the issue area, but also to incorporate material from your class readings and sessions into the memo so your recommendations for practice are informed by what you have learned in your class. This assignment consists of three components for a total of 40% (5+5+30%) of your course grade, as explained below: At two points during the semester, you will be asked to present two 500 word papers, each worth 5% of your course grade, of: a) the topic for your project, including a clear summary of the human rights problem, values and mission of the organization you have chosen to work with, and the relevant human rights law and norms (due at the beginning of class on October 1); and b) your proposed strategies and tactics to address the problem (due at the beginning of class on October 29). 4 You will receive written comments on these 2 page papers, which can later be fully or partially incorporated into the final memo. A paper copy of your paper should also be brought to class to share with a fellow student to receive written feedback from a peer on both the quality of the ideas and the style of writing; you should receive a copy of another student’s paper for your own editing comments. The Final Strategic Policy Memo should include: A clear statement of the human rights problem you wish to affect and how it relates to relevant human rights law and norms, and to the goals and mission of the organization you have chosen. The strategy you intend to implement and the tactics needed to do so, including the alliances and networks you will need to link to your project. Draw on readings from class on the causes of human rights violations and the conditions under which action can be effective to explain why you have chosen this strategy and these tactics, and/or to explain why the strategy is important but could be difficult to implement. Include a discussion of the powers and interests that may resist your project and how you will deal with them. Justification from the readings from class regarding why you think your plan is likely to be effective in securing greater commitment and/or compliance with human rights norms or law. A copy of the tactical map you developed to help you identify targets, tactics, and timing for your intervention(s). Reference to authors by name in text, including full citation in the bibliography. If you are in doubt about whether or not to cite, see discussion of academic integrity below. The final memo will be due December 11 at 12:00 noon. Late memos will be heavily penalized. The final memo counts for 30% of your course grade. 3. Written feedback to peers: Each student should bring an extra copy of their short, strategy preparation writing to class (October 1 and October 29) to exchange with another student. Each student receiving a paper should provide written feedback to the writer (considering grammar, clarity of ideas, logic of the proposals, and suggestions for improved writing). The next class session will have time to discuss this feedback. Photocopies of the feedback should be provided to the instructor on that date. Each feedback session will be worth up to 5% of the course grade. Writing Coaches at HKS: Students who are unfamiliar with academic writing, or who have little practice writing in English, may experience challenges in completing written assignments for this course. The Communications Program at HKS is an excellent resource for any student who needs help in strengthening or refining a written essay. Please see the following web page for information on working with a writing consultant: http://shorensteincenter.org/students/communications-program/writing-consultants/. 5 Enrollment: Auditing is limited and by permission of instructor and only with a written agreement about the work the auditor will accomplish as part of the course. Those taking the course for credit have precedence at office hours. Grading: The HKS Academic Council has issued recommendations on grading policy, which include the following curve: A (10-15%), A- (20-25%), B+ (30-40%), B (20-25%), B- (5-10%). Academic Integrity: “We expect you to express your ideas and to sustain arguments in your own words. Failure to do so is plagiarism. It is unethical and often illegal. Plagiarism ranges from the blatant—purchasing a term paper or copying on an exam—to the subtle—failing to credit another author with the flow of ideas in an argument. Properly acknowledging the use of the words of others and avoiding excessive quotation of the work of others will eliminate most plagiarism problems. If you want to quote from a published work, including a Web page, you must put the passage in quotation marks and provide a citation. Simply changing a few words from the writings of other authors does not alter the fact that you are essentially quoting from them. Paraphrasing of this sort, where you use the words of another almost verbatim without acknowledging your source is the most common form of plagiarism among undergraduates. When you state another author's viewpoint, theory, or hypothesis—especially when it is original or not generally accepted—you must also include a reference to the published work. In general, citations are unnecessary when the information is considered common knowledge or a matter of widespread agreement. Common knowledge can often be identified by its appearance in several of the assigned readings for class…. Failure to maintain academic integrity in any portion of the academic work for the course shall be grounds for awarding a grade of F for that assignment.” (This paragraph was drawn in its entirety from Clark Miller’s syllabus at: http://www.hks.harvard.edu/sdn/syllabi/files/Miller-Science_and_Democracy.pdf) Course Page and Reading Materials: The course page is available over the HKS Intranet. Go to the HKS home page. Select the login button on the screen. Enter your username and password. Select IGA385 in Course Listings and you’re in. If you are not an HKS student and need access to the course page, there is a procedure connected to the cross-registration process. Auditors can also be accommodated through this same process. Most course readings are posted on the class page, but two books should be purchased at the Harvard Coop in the Textbook Department. Both books are on hold at the Library. The two book titles are: 6 Beth Simmons, Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2009), and Andrew Clapham. Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2007). 7 Daily Topics and Required Readings: Session 1, September 3, 2015. Overview of Course and Introduction to Strategic Concepts of the Class. Required reading: “Coal Mining in Mozambique” Draft Multimedia Case, HKS Slate Program (posted on course page; see instructions in Announcements section) Andrew Clapham. Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2007) Chapter 1, “Looking at Rights,” and Chapter 2, “The Historical Development of International Human Rights,” pp. 1-56. (book) Session 2, September 8, 2015. What constitutes human rights practice? Guest speaker: John Shattuck, President and Rector, Central European University. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Shattuck) Required reading: John Shattuck, “Introduction,” Freedom on Fire: Human Rights Wars and America’s Response, Harvard University Press, 2003 (pp. 1-20). Claude Welch, Jr., “Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, A Comparison,” NGOs and Human Rights: Promise and Performance, (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press: 2000), pp 85-112. (posted on course page) Hurst Hannum, Guide to International Human Rights Practice, 3d ed, Ardsley: Transnational Publishers, Inc. (1999), pp. 19 – 38. (posted on course page) Session 3, September 10, 2015. What is strategy? Required reading: Marshall Ganz, “Introduction: How David Beat Goliath,” Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement (Oxford University Press, 2009), Chapter 1, pp 3-21. (posted on course page) Lawrence Freedman, Chapter 38 , “Stories and Scripts,” Strategy: A history,” Oxford University Press, 2013. Pp 607-632. Sun Tzu, Chapter 1, “Estimates,” The Art of War, Translation by Samuel B. Griffith, Oxford University Press, 1963. Pp. 63-71 (posted on course page and on reserve in the library) 8 Douglas A. Johnson, “The Need for New Tactics,” New Tactics in Human Rights: A resource for Practitioners, Center for Victims of Torture, Minneapolis, 2004, (pp. 12-19). https://www.newtactics.org/sites/default/files/resources/02needfornewtactics.pdf (posted on course page) Session 4, September 15, 2015. Applying strategic frameworks to practice. Required reading: Don Hubert, “The Landmine Ban: A Case Study in Humanitarian Advocacy,” Occasional Paper #42, Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies, 2000. http://www.watsoninstitute.org/pub/op42.pdf (posted on course page) Session 5, September 17, 2015. Defining the Terrain Douglas A. Johnson and Nancy L. Pearson, “Tactical Mapping: How Nonprofits Can Identify the Levers of Change,” in The Non-Profit Quarterly (Summer 2009), pp. 92-99. (posted on course page) UN OHCHR Manual Chapter on Relationship Mapping (posted on course page) Review again the Hubert article. Session 6, September 22, 2015. Human Rights Treaty Drafting and Ratification: Who writes human rights law and why do states commit to it? Required reading: Beth Simmons, Chapter 2, “Why International Law? The Development of the International Human Rights Regime in the 20th Century,” and Chapter 3, “Theories of Commitment,” in Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 23-111. (book) Session 7, September 24, 2015. Naming and Shaming and the Need for Broader Array of Tactics Required Reading: HKS Case on Female Genital Cutting: (Multi-media case), https://knet.hks.harvard.edu/Administration/Case_Program/MultimediaCases/FGC/Pages/Introdu ction.aspx (posted on course page) 9 Gerry Mackie, “Ending Footbinding and Infibulation: A Convention Account,” American Sociological Review 61:6 (December 1996): pp. 99-1017. (posted on course page) Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Chapter 2, “Historical Precursors to Modern Advocacy Networks,” Activists beyond Borders; Advocacy Networks in International Politics, Cornell University Press (Ithaca: 1998), pp. 39-78. (posted on course page) Session 8, September 29, 2015. Transnational Civil Society and Advocacy Networks Required Reading: Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Chapter 1, “Transnational Advocacy Networks and International Politics: Introduction,” Activists beyond Borders; Advocacy Networks in International Politics, pp. 1-38. (posted on course page) Amanda M. Murdie and David R. Davis. "Shaming and Blaming: Using Events Data to Assess the Impact of Human Rights INGOs." International Studies Quarterly (2012, 56:1), pp. 1-16. (posted on course page) Tarrow, Sidney. 2011. Power in Movement, 3rd ed (Cornell University Press), Introduction and Chapter 1. Session 9, October 1, 2015. Political and economic explanations for human rights violations. 500 word description of topic for policy memo, due at the beginning of class. Required reading: Amartya Sen, “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing,” New York Review of Books, Vo. 37, No. 20 December 20, 1990, pp. 1-13. (posted on course page) Amartya Sen, "Freedoms and Needs: An Argument for the Primacy of Political Rights," The New Republic Volume 210 Issue 2/3 January 10 and 17, 1994, pp. 31-38 (posted on course page) Todd Landman and Marco Larizza, “Inequality and Human Rights: Who Controls What, When, and How,” International Studies Quarterly 53:3 (2009): pp. 715-736. (posted on course page) Steven C. Poe, C. Neal Tate, and Linda Camp Keith, "Repression of the Human Right to Personal Integrity Revisited: A Global Cross-National Study Covering the Years 1976-1993," International Studies Quarterly, Volume 43, Issue 2 (June1999) pp. 291-313. (posted on course page) 10 Session 10, October 6, 2015. Ideological and Psychological Explanations for the Causes of Human Rights Violations. Required reading: Phillip Zimbardo, “When Good People Do Evil,” Yale Alumni Magazine Jan/Feb 2007, pp. 4047 (read at: http://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/current/milgram.html) (posted on course page) Janice T. Gibson and Mika Haritos-Fatouros, "The Education of a Torturer," Psychology Today (November 1986), pp. 50-58. (posted on course page) Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, chapter 4, “The Humanitarian Revolution,” pp. 129-188. Recommended: Think about the explanations of the, HKS Case on Female Genital Cutting in the context of today’s readings and theme. Session 11, October 8, 2015. U.S. and the Case of Torture: Guest lecturer, Alberto Mora, Esq., Harvard Advanced Leadership Fellow Kathryn Sikkink, “Is the US Immune to the Justice Cascade?” in The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions are Changing World Politics, WW Norton (New York, 2011), pp. 189-222. (posted on course page) Jane Mayer, “The Memo,” in The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals, New York: Doubleday, 2008, pp. 213-237. (posted on course page) Douglas Johnson, “Testimony to US Congress,” January 6, 2005. (posted on course page) Recommended: Beth Simmons, Chapter 7, “Humane Treatment: The Prevalence and Prevention of Torture,” Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2009). Pp. 256-306. (book) Andrew Clapham, Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2007), Chapter 4, “The International Crime of Torture,” pp. 81-95. (book) Session 12, October 13, 2015. Linking relationships, targets, and tactical interventions 11 Required Reading: Peter Finn and Anne Kornblut, “Guantanamo Bay: Why Obama hasn’t Fulfilled his Promise to Close the Facility,” Washington Post, April 23, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/guantanamo-bay-how-the-white-house-lost-the-fight-toclose-it/2011/04/14/AFtxR5XE_story.html (posted on course page) Alex Abdo, “Reporting from Guantanamo: The Five Uns,” ACLU Blog of Rights, July 23, 2012, https://www.aclu.org/blog/national-security-human-rights/reporting-guantanamo-five-uns (posted on course page) Session 13, October 15, 2015. Fighting Bonded Labor in Rural India Required reading: HKS Case, “Fighting Bonded Labor in Rural India: Village Activist Gyarsi Bai Tackles an Entrenched System of Coercion” (posted on course page) Austin Choi-Fitzpatrick, A Human Rights Approach To Contemporary Slavery, Unpublished Manuscript, pp. 1-18. (posted on course page) Session 14, October 20, 2015. Compliance with human rights norms. Required Reading: Beth Simmons, Chapter 4: “Theories of Compliance,” and Chapter 9: “Conclusions.” In addition, class working groups will be assigned to read one of the following four chapters to prepare for class discussion: Chapter 5, “Civil Rights,” Chapter 6, “Equality for Women: Education, Work, and Reproductive Rights,” and Chapter 8, “the Protection of Innocents: Rights of the Child,” in Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009 pp. 112-380. (Come prepared with your group to present the main findings of the empirical chapter you read and how it relates to Simmons’s analytical framework.) (book) Session 15, October 22, 2015. Forming Strategic Alliances Required Reading: Erika Bocanegra, Together We Are Stronger: Peru's National Coordinating Coalition on Human Rights, A Tactical Case Study published by the New Tactics Project of the Center for Victims of Torture, 2005. (24 pages) http://www.newtactics.org/sites/default/files/resources/TogetherStronger-EN.pdf (posted on course page) 12 Alexander Cooley and James Ron, “NGO Scramble: Organizational Insecurity and the Political Economy of Transnational Activism,” International Security, 2002, 27(1): 5-39. (posted on course page) Review the case “Protecting the Inter-American System of Human Rights,” http://hrcases.org/#/caso/4/1 Session 16: October 27, 2015 Importance of domestic mobilization. Required reading: Nikolayenko, Olena, “Origins of the movement’s strategy: The case of the Serbian youth movement Otpor,” International Political Science Review, 34/2: March 2013. (posted on course page) Chenoweth, Erica, and Maria J. Stephan, “The Primacy of Participation in Nonviolent Resistance,” Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Columbia UP, 2011, pp.30-61. (posted on course page) Tavana.Org, “The Year Life Won in Serbia: The Otpor Movement Against Milosovic,” https://tavaana.org/en/content/year-life-won-serbia-otpor-movement-against-milosevic-0 Session 17, October 29, 2015. Understanding the UN mechanisms to protect human rights. The second 500-word memo is due at the beginning of class. Required reading: Andrew Clapham, Chapter 3, “Human Rights Foreign Policy and the Role of the United Nations,” from Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 57-80. (book) Jo Becker, “Working with UN Special Rapporteurs to Promote Human Rights,” Campaigning for Justice, Human Rights Advocacy in Practice, Stanford University Press (Stanford, CA: 2013), pp. 77-94. (posted on course page) Miloon Kothari, “From Commission to the Council: Evolution of UN Charter Bodies,” in (Dinah Shelton, ed.) The Oxford Handbook of International Human Rights Law, (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 587-620. (posted on course page) Session 18, November 3, 2015. International Organizations and the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights Required reading: 13 Ted Piconne, Introduction, Chapter 1, “Who are the UN Independent Experts,” and Chapter 2, “Findings on Effectiveness,” Catalysts for Change: How the UN Independent Experts Promote Human Rights, Brookings Institution Press (Washington, 2012) pp. 1-44. (posted on course page) Ann Marie Clark, “The Normative Context of Human Rights Criticism: Treaty Ratification and UN Mechanisms,” The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance, edited by Risse, et. al. (Cambridge: 2012), pp. 125-144. (posted on course page) Heyns, Padilla & Zwaak: “A schematic comparison of regional human rights systems,” Sur, International Journal of Human Rights, Nr. 4 (posted on course page) Session 19, November 5, 2015. Case: Treatment Action Campaign, South Africa. Required reading: Mark Heywood, “South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign: Combining Law and Society Mobilization to Realize the Right to Health,” Journal of Human Rights Practice Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2009), pp. 14-36. Constitutional Court of South Africa, Soobramoney v Minister of Health, KwaZulu-Natal, 1997. Session 20, November 10, 2015. Social, Economic and Cultural Rights Required reading: Andrew Clapham, Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2007), Chapter 7, “Food, Education, Health, Housing and Work,” pp. 119-142. (book) Balakrishnan Rajagopal, “Limits to Law in Counter-Hegemonic Globalization: The Indian Supreme Court and the Narmada Valley Struggle,” in Law and Globalization from Below: Towards a Cosmopolitan Legality, edited by Boaventura de Sousa Santos and César Rodríguez Garavito (Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 183-217. (posted on course page) Session 21, November 12, 2015. Transnational Corporations and Human Rights Required reading: John Ruggie, Chapter 1, “The Challenge,” in Just Business: Multinational Corporations and Human Rights (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), pp. 1-33. (posted on course page) Douglas A. Johnson, “Confronting Corporate Power: Strategies and Phases of the Nestle Boycott,” from Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy,” edited by James E. Post, JAI Press, Inc., Greenwich, CT, 1986 (pp. 323-344). (posted on course page) Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Guiding Principles on Business and Human 14 Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect, Remedy” Framework (United Nations, 2011), skim document. (posted on course page) http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/GuidingPrinciplesBusinessHR_EN.pdf Session 22, November 17, 2015. Multi-stakeholder alliances and non-state actors David Beffert and Thorsten Benner, “Stemming the Tide of Conflict Diamonds: The Kimberley Process,” Hertie School of Governance Case Program, Berlin, 2005. (posted on course page) Session 23: November 19, 2015. Can Accountability for Past Human Rights Violations prevent future crimes? Required reading: Kathryn Sikkink, Chapter 1, “The Introduction,” and Chapter 6, “Global Deterrence and Human Rights Prosecutions,” The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions are Changing World Politics, pp.1-30 & 162-188. (posted on course page) James D. Meernik, Angela Nichols, and Kimi L. King, “The Impact of International Tribunals and Domestic Trials on Peace and Human Rights after Civil War,” International Studies Perspectives, (2010) 11, 309-334. (posted on course page) Session 24: November 24, 2015. Review of Cases and Strategic Concepts Required reading: Review case notes from semester. November 26, 2015. NO CLASS FOR THANKSGIVING Session 25: December 1, 2015. Student presentations Session 26: December 3, 2015. Coal Mining in Mozambique . Human Rights Watch, “What is a House Without Food?” (posted on course page) “Coal Mining in Mozambique” Draft Multimedia Case, HKS Slate Program (posted on course page; see instructions in Announcements section) Final papers are due December 11 at 12 noon and must be submitted electronically. 15