File - (LMG) Project

advertisement

Leadership, Management and Governance (LMG) Project

Inspired Leadership. Sound Management. Transparent Governance.

Cooperative Agreement Number AID-OAA-A-11-00015

SYNTHESIS PAPER ON EFFECTIVE GOVERNANCE FOR HEALTH

DATE: 30 June 2012

Submitted to:

Brenda A. Doe

Deputy Division Chief, Services Delivery Improvement Division

Room 3.6-123, Office of Population & Reproductive Health

Bureau of Global Health, USAID

1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20523

Submitted by:

Management Sciences for Health (MSH)

James A. Rice, Ph.D.

Project Director, Leadership, Management and Governance Project

In Collaboration with:

Implementing project partners include the African Medical and Research Foundation, International

Planned Parenthood Federation, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Medic

Mobile, and Yale University Global Health Leadership Institute.

Acronyms

GEN-RH Global Exchange Network for Reproductive Health

LMG Leadership, Management and Governance Project

MSH Management Sciences for Health

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

USA United States of America

USAID Untied States Agency for International Development

WHO World Health Organization

Funding was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement

AID-OAA-A-11-00015. The contents are the responsibility of the Leadership, Management, and Governance Project and do

not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

2 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Table of Contents

Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... 5

Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 7

Methods ......................................................................................................................................... 9

Quantitative survey ................................................................................................................... 9

In-depth interviews.................................................................................................................... 9

Results ......................................................................................................................................... 10

Quantitative survey ................................................................................................................. 10

Respondent profile ................................................................................................................ 10

Elements or practices of governing....................................................................................... 11

Enablers and impediments for effective governance ............................................................ 12

Linkages between effective governance, improved health services, and improved health of

individuals and the population .............................................................................................. 13

Relationships and interaction between leadership, management, and governance .............. 14

Subgroup analysis ................................................................................................................. 14

In-depth interviews.................................................................................................................. 14

Respondent demographics .................................................................................................... 14

Participant experiences of leading, governing and managing ................................................. 16

What is governance? ............................................................................................................. 16

Elements or practices of governance .................................................................................... 16

Effective governance in the context of health....................................................................... 17

Linkage between governance and health outcomes .............................................................. 18

Measuring governance .......................................................................................................... 18

Gender in governance ........................................................................................................... 19

Inter-relationship and interaction of leadership, management and governance ................... 20

Discussion.................................................................................................................................... 20

Limitations .................................................................................................................................. 21

Quantitative survey ............................................................................................................... 21

In-depth interviews ............................................................................................................... 22

Policy Implications ..................................................................................................................... 22

References ................................................................................................................................... 25

Appendix ..................................................................................................................................... 27

Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 27

Tables ...................................................................................................................................... 39

Subgroup Analysis .................................................................................................................. 60

Gender ................................................................................................................................... 60

Sectors ................................................................................................................................... 61

3 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Levels .................................................................................................................................... 61

Country where respondent works ......................................................................................... 62

Geographical regions: Asia, Africa, Latin America and Caribbean ..................................... 63

Respondents who govern vs. respondents who manage but not govern ............................... 64

Respondents who govern vs. respondents who lead but not govern..................................... 65

Survey instruments .................................................................................................................. 66

Quantitative survey ............................................................................................................... 66

In-depth interview protocol................................................................................................... 73

4 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Abstract

Background

Poor governance, overall and especially in the health sector, has contributed to poor health

outcomes in many low and middle income countries. There is evidence in the literature that

shows effective governance improves health outcomes. Published empirical literature on how

people who lead, govern and manage perceive governance in the context of health is very

limited.

Methods

We sought to understand governance, and what makes it effective in the context of health from

the perspective of people who lead, govern or manage the health sector or the health institutions

in low and middle income countries through a quantitative on-line survey of 477 respondents in

80 countries in addition to a qualitative survey of 25 key informants in 16 countries.

Results

Our salient survey findings are (1) Those who lead, govern and manage the health sectors and

health institutions are likely to define effective governance in terms of improvements in both the

health services and the health of individuals and populations. Many (more females than males)

see a clear link between governance in sectors other than health as having an effect on the health

of individuals and populations. (2) Leadership, management, and governance are highly interlinked and mutually reinforcing constructs in the context of health. Leaders are critical to the

governing process, and effective leadership is a prerequisite for effective governance and

effective management. (3) Including the governed in the governing process, steering and

regulation, collaboration across ministries, sectors and levels, and oversight were judged to be

highly significant elements of the governing process. (4) Competent leaders with ethical and

moral integrity, measurement and use of data, sound management, adequate financial resources

available for governing, openness and transparency, participatory decision making,

accountability to the citizens and clients, use of scientific evidence and effective governance in

sectors other than health, and governing using technology were judged as the top enablers of

effective governing in the context of health. (5) Governance needs to be gender aware, gender

responsive, and gender transformative in order to be effective.

Conclusion

Leaders who govern in low and middle income countries and who wish to achieve better health

outcomes for their constituents should, according to their peers, consider cultivating integrity,

transparency, accountability, leadership, community participation, intersectoral collaboration,

performance measurement, and gender responsiveness; and use technology as they foster these

attributes in their governing.

Keywords

Governance, governing, effective governance, governance for health, governing for health,

deterrents, enablers, practices, measuring governance, gender in governance, leadership,

management

5 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

KEY MESSAGES

Effective governance in the context of health is governance that leads to improvements in

both the health services and the health of individuals and populations.

Leaders are critical to the governing process, and effective leadership is a prerequisite for

effective governance and effective management.

Including the governed in the governing process, steering and regulation, collaboration across

ministries, sectors and levels, and oversight were judged to be highly significant elements of

the governing process.

Top enablers of effective governing in the context of health include: competent leaders with

ethical and moral integrity, measurement and use of data, sound management, adequate

financial resources available for governing, openness and transparency, participatory decision

making, accountability to the citizens and clients, use of scientific evidence, and effective

governance in other sectors.

6 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Introduction

Poor governance, overall and especially in the health sector, has contributed to poor health

outcomes in many low and middle income countries. Our review of literature shows this link

between governance and health outcomes. Gupta et al. (2000) showed that levels of corruption

are clearly related to child mortality and other health outcomes, and a two-point improvement in

the integrity of government would reduce child mortality by 20%. Corruption was found to be

negatively associated with the quality of health services as proxied by the health staff’s

knowledge on required immunizations (Azfar, et al. 2001). A study of 64 countries found that

corruption lowered public spending on education, health and social protection (Delavallade

2006). Lindelow and Serneels (2006) in their focus group discussions with health workers and

users of health services found the failure of government policies and weak accountability

mechanisms as two of the four structural reasons for performance problems in the health sector.

Controlling for several variables including female education, income, urbanization, and distance

from the equator, Rajkumar and Swaroop (2008) showed that public health spending has a

greater effect on child and infant mortality the higher is the quality of government– measured

both as the absence of corruption and the quality of the bureaucracy.

There is further evidence that shows that effective governance improves health outcomes. Public

health spending lowers child mortality rates more in countries with good governance, and the

differences in the efficacy of public spending can be largely explained by the quality of

governance (Rajkumar and Swaroop 2008). Governance was strongly associated with under-five

mortality rate, and after controlling for possible confounding by healthcare, finance, education,

and water and sanitation, governance remained significantly associated with it (Olafsdottir et al.

2011). Probably the best evidence comes from the randomized field experiment conducted by

Björkman and Svensson (2009) in fifty rural communities of Uganda to see if community

monitoring of providers improves health outcomes. In the treatment group, a community, with

the help of a local community-based organization, monitored primary health care providers of

the public dispensary for a year using a citizen report card. At the end of one year, they found

that community monitoring had increased the quality and quantity of primary health care;

utilization of out-patient services was 20 percent higher in treatment communities; treatment

practices, examination procedures, and immunization coverage all improved; and perhaps most

importantly, there was a significant increase in weight of infants and as much as 33 percent

reduction in under-5 mortality in the treatment communities as opposed to the control

communities. In an experimental analysis, Barr et al. (2009) found that monitors are more

vigilant when they are elected by service recipients, and service providers perform better when

they are monitored by monitors so elected.

Since governance appeared to directly impact health system performance and health outcomes,

leadership and governance became salient during the past decade. Saltman and Ferroussier-Davis

(2000) had reviewed the concept of stewardship as a model of governance in the context of

World Health Report 2000 (Reinhardt and Cheng 2000) and defined it as a pursuit of policymaking that is both ethical and efficient. Different conceptual frameworks have been proposed

since then to define and measure governance in the context of health. Siddiqi et al. (2009) have

considered four existing frameworks: the World Health Organization’s domains of stewardship;

the Pan American Health Organization’s essential public health functions; the World Bank’s six

basic aspects of governance; and the United Nations Development Programme principles of good

7 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

governance. Based on their review of existing frameworks, Siddiqi et al. proposed their Health

System Governance assessment framework that has 10 principles that underpin 63 broad

questions ranging from contextual and descriptive to process and outcome-related.

Recently, Veillard et al. (2011) revisited the concept of stewardship through a multidisciplinary

review of the literature and derived an operational framework comprising six functions of

stewardship for assessing the overall stewardship function of national health ministries.

Kickbusch and Gleicher (2011) advise combining whole-of-government and whole-of-society

approaches in their study conducted for the WHO Regional Office for Europe. They define smart

governance for health in terms of how governments approach governance challenges

strategically in five dimensions; by 1) governing through collaboration (how the state and society

co-govern), 2) governing through citizen engagement, 3) governing by a mix of regulation and

persuasion, 4) governing through independent agencies and expert bodies, and 5) governing by

adaptive policies, resilient structures and foresight. Mikkelsen-Lopez et al. (2011) proposed a

framework based upon a systems thinking approach, which is problem-driven and considers the

major health system building blocks at various levels in order to ensure a complete assessment of

a governance issue with a view to strengthen system performance and improve health.

Health Systems 20/20, a USAID-funded project, measured five dimensions of governance in the

health sector: information/assessment capacity, policy formulation and planning, social

participation and system responsiveness, accountability, and regulation. Brinkerhoff and Bossert

(2008) define good health governance in terms of roles and responsibilities and relationships that

are governed by; 1) responsiveness to public health needs and beneficiaries’ or citizens’

preferences while managing divergences between them; 2) responsible leadership to address

public health priorities; 3) the legitimate exercise of beneficiaries’/citizens’ voice; 4) institutional

checks and balances; 5) clear and enforceable accountability; 5) transparency in policymaking,

resource allocation, and performance; 6) evidence-based policymaking; and 7) efficient and

effective service provision arrangements, regulatory frameworks, and management systems.

Smith et al. (2012) present a cybernetic model of leadership and governance comprising three

fundamental functions: 1) priority setting, 2) performance monitoring and 3) accountability

mechanisms. In addition, there are frameworks that look at governance of a part of a health

system e.g. Good Governance in Medicines Framework of WHO (Anello 2008) and

Pharmaceutical Governance Model of USAID-funded Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems

Project (SPS 2011).

Despite these advancements in the theoretical understanding of governance in the context of

health, there is very limited empirical literature on how people who lead, govern and manage in

low and middle income countries perceive effective governance in the context of health.

Systematically looking at governance in the context of health through the eyes of the people who

lead, govern and manage becomes important if the approaches, processes, models, interventions

and tools aimed at enhancing governance are to be firmly grounded in the perspectives of this

target population.

To add to the limited body of knowledge surrounding governance in health, we conducted a

quantitative survey of 477 health leaders, governors and managers from 80 countries and

qualitative in-depth interviews of 25 key health leaders, governors and managers from 16

8 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

countries to assess their perceptions on effective governance in the contest of health. We report

the findings of these two surveys in this article.

Methods

The same set of research questions guided the quantitative and qualitative enquiries; these were:

what constitutes governance,

what constitutes effective governance,

what constitutes effective governance in the context of health,

what are the enablers and deterrents of governance,

how does governance relate to health system outcomes and health outcomes,

how is governance measured,

what are the gender issues involved in governance, and

how does governance, leadership and management interact in the context of health.

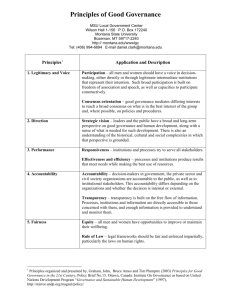

The two surveys sought perceptions and perspectives of the respondents on these questions. The

survey and interview instruments were created based upon a conceptual model of governance for

health depicted in Figure 1 in the Appendix. This governance model was derived from the

targeted literature review examined earlier in this paper as well as discussions with experts and

practitioners in the field, and also the findings of 2011 survey on governance for health. These

two instruments were extensively pilot-tested before administration. The New England

Institutional Review Board, via expedited review, approved the research protocol. The free and

informed consent of each key informant interviewees was obtained prior to the interview.

QUANTITATIVE SURVEY

The online survey was conducted between February 20 and March 24, 2012. The survey was

administered to the members of LeaderNet and the Global Exchange Network for Reproductive

Health (GEN-RH), two online communities of practice of health leaders, managers and those

who govern in the health sector. LeaderNet (http://leadernet.msh.org) is a global learning

community of managers who lead and leaders who govern in the health sector and in health

institutions. GEN-RH is a web-based network of individuals and organizations working in the

area of reproductive health. Management Science for Health (MSH) currently supports the two

communities of practice. A link to the survey instrument was sent via e-mail to approximately

6,000 health leaders, managers, and those who govern in public, private, and civil society sectors

in primarily low and middle income countries. The survey had 15 questions, and was

administered in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese. A total of 477 responses were received

from respondents who completed the survey in the following languages: English (274), Spanish

(122), French (66), and Portuguese (15). Survey response rate and other limitations are discussed

later in the paper. The survey data was analyzed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

Using a purposeful sampling strategy, we recruited as our key informants people who lead,

govern, and manage the health sector (and other relevant sectors in a few instances) or the health

institutions in low and middle income countries who could provide insights into leading,

governing and managing as they relate to potential health outcomes. The informants were wellrespected health professionals in their countries and had no prior association with the

9 LMG Project Year 1

September 2011 – June 2012

organization (MSH) or the project (LMG Project) to which the researchers belonged. The

consenting informants were interviewed in person or on telephone by the principal investigator

or the associates using an open-ended interview guide (See Appendix). Seventeen (68%) of our

informants said they lead and govern, 5 (20%) informants said they lead and manage, and 3

(12%) said they lead. The goal was to interview those closely associated with the process of

governing. Those who lead and govern deliver governance decisions, and those who

predominantly lead and manage receive governance decisions. We tried to ensure that these

diverse perspectives are reflected in the study. The interview was semi-structured and an

informant was allowed to guide the conversation.

Interviews were conducted in Spanish 7 (28%) and in English 18 (72%). Spanish language

interviews were conducted by bilingual health services researchers. For analyses, all interviews

were transcribed and those interviews conducted in Spanish were translated into English. We

used bilingual interviewers in case of Spanish speaking interviewees and this may have increased

the likelihood of conceptual equivalence of issues thus reducing the potential for

misunderstanding and misinterpretation.

We generated an index of taxonomies, themes and subthemes based on our literature review,

findings of 2011 governance survey, discussion with experts, and patterns that emerged during

the key informant interviews. The text data resulting from interviews was coded by the two

researchers who compared their notes during and after the coding process. NVivo version 9 was

used for the data management and analysis. Analysis was an iterative process in which the

researchers collaborated to reach consensus on themes and sub themes at key points throughout

the research. Additional themes were added as they emerged. We searched the whole of the text

data for recurrent unifying concepts or statements while distilling themes and sub themes that

explain, predict, or interpret effective governance in the context of health and its link to health

system performance and health outcomes.

Results

QUANTITATIVE SURVEY

Respondent profile

A total of 477 leaders, managers and people who govern from 80 countries (See Table 1 in

Appendix) responded to the survey. Of the respondents, 60% were male and 40% were female.

The vast majority of respondents (88%) lived and worked in low and middle income countries.

By region, 48% of the respondents were from Africa, 35% from Latin America and the

Caribbean, 11% from Asia, and 6% from the USA, Canada, and Europe. When asked what sector

they work in, 50% of the respondents said that they work in the public sector, 27% in civil

society organizations, 15% in the private sector, and 8% in other sectors. By level of the health

system, 53% of the respondents work at the national level, 34% at the state level, and 41% at the

local level. The respondents could check multiple levels if they worked at multiple levels.

Seventeen percent (17%) work regionally with groups of nations. Less than 10% of the

respondents indicated they work at the global level.

10 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Viewed from the standpoint of the six WHO building blocks of health systems, most respondents

work within multiple health system building blocks with a focus on multiple service delivery

areas (See Figure 2 in Appendix). Each respondent was asked whether they lead, manage,

govern, and/or observe others govern: 85% reported that they lead, and 85% say they manage,

while only 32% reported that they govern. In addition, 85% stated that they observe others

govern (See Figure 3 in Appendix). About 30% of the respondents also stated that they lead,

manage, and govern. This indicates that there is a clear overlap among the roles of leading,

managing, and governing. No respondent stated he or she governs but does not manage or lead,

indicating that when governance is exercised it is done while leading and managing.

Respondents who govern also lead and manage. Respondents who manage also lead.

Elements or practices of governing

The survey sought to explore what governance means in practical terms for the respondents. In

other words, what do people who govern do to govern? The respondents were asked the degree

to which they consider each of the six practices indicated by an action verb in Table 2 and their

corresponding activities as part of the governing process. The action verbs were derived from the

targeted literature review and discussions with experts and practitioners in the field.

Table 2: Elements/Practices of governing

Practice

Steer

Regulate

Allocate

Include

Collaborate

Oversee

Activities

To identify a policy problem, to advocate policy, to set policy agenda, to have

a policy dialogue, to decide a strategic direction, to analyze policy options, to

make sound policies, and use continual learning in refining and adapting

policies for the future

To formalize policies through laws, regulations, rules of procedure, protocols,

standard operating procedures, or resolutions, etc.

To allocate responsibility of policy implementation and also authority and

resources to carry out that responsibility through any of the legally enforceable

instruments stated above

To communicate and engage with the governed, to provide information, to

promote dialogue, to engender trust, to allow representation, to establish

systematic feedback mechanisms, to respond to the feedback received, to

explain to the governed the changes made in response to their feedback, to

enable openness, transparency, and accountability, and to resolve conflicts

whenever they arise

To collaborate across levels (local, state or a province, national, regional and

global) and across sectors (public, private, and civil society), to design and

establish a process for such collaborations, to establish alliances, networks and

coalitions, to adopt whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches,

and to persuade actors across sectors and across levels for joint action

To communicate expectations to the policy implementers, watch and appraise

the evaluation of implementation of policies, and use sanctions when necessary

11 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

There is strong agreement among these respondents that “Include” and “Steer” are two

prominent governance practices (See Figure 4 below): fully 75% of the respondents stated that

both “Include” and “Steer” are a highly significant parts of the governing process. “Regulate,”

“Collaborate,” “Oversee,” and “Allocate” are also perceived as highly significant elements of the

governing process by 67%, 63%, 60% and 58% of the respondents, respectively. Ninety-two

percent of the respondents indicated that both “include” and “steer” are highly or moderately

significant elements of the governing process, while 89%, 88% 87% and 85% indicated the same

for “collaborate”, “regulate”, “allocate” and “oversee”, respectively.

Figure 4: Defining governing in practical terms (N=404)

100%

6%

5%

90%

80%

17%

8%

8%

21%

26%

8%

9%

is not a part of

governing at all

17%

70%

25%

29%

is a slightly significant

part of governing

60%

50%

40%

75%

is a moderately

significant part of

governing

75%

67%

30%

63%

60%

58%

20%

is a highly significant

part of governing

10%

0%

To include

To steer

To regulate

To collaborate

To oversee

To allocate

Enablers and impediments for effective governance

When queried about 15 potential enablers and impediments to effective governance for health

listed in the survey, the respondents indicated factors they thought enabled or deterred effective

governance, the top ten of which are stated in Table 3. According to the respondents, “governing

with ethical and moral integrity” and “competent leaders governing in the health sector” are the

two most important facilitators. The majority of the respondents saw governing with the enablers

in place leading to both improvements in health services and in health. Figures 5 and 6 in the

Appendix graphically display the survey responses on enablers and impediments for effective

governance.

12 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Table 3: Top ten enablers and deterrents of effective governance

#

1

2

Deterrent

Ineffective leadership

Corruption

3

Ineffective management

4

5

Inadequate transparency

6

Inadequate systems to collect, manage,

analyze and use data

7

8

9

Inadequate accountability

Inadequate participation of community/

citizens/ clients/ consumers/ patients

Political context

Inadequate checks and balances

10 Inadequate financial resources for

governance

#

1

Enabler

Governing in health sector with ethical

and moral integrity

2 Competent leaders governing in health

sector

3 Governing in health sector with a definite

policy on measurement, data gathering,

analysis, and use of information for policy

making

4 Sound management of health sector

5 Adequate financial resources available for

governing in health sector

6 Governing in health sector in open and

transparent manner

7 Governing in health sector with

client/community participation in decision

making process

8 Governing in health sector with

accountability to citizens/clients

9 Governing in health sector based on

scientific evidence

10 Good Governance in sectors other than

health

Linkages between effective governance, improved health services, and improved health of

individuals and the population

The survey sought to understand how the respondents defined effective governance in the

context of health (See Figure 7 in Appendix). Fully 75% of the respondents answered that

effective governance in the context of health is governance that leads to both an improvement in

health services and the health of individuals and populations.

The linkage between effective governance and improved health services

The respondents were further asked to indicate the extent to which effective governance in the

health sector leads to specific health service outcomes (See Figure 8 in Appendix). In order of

importance, the respondents indicated that effective governance leads “to a large extent” to the

following health service outcomes: services become effective (78%); access to and coverage of

the service increase (77%); clients are satisfied (77%); services become efficient (75%); and

services become sustainable (75%). Respondents perceive a very strong link between effective

governance and improvements in quality of health service.

The linkage between effective governance and improved health of individuals and the population

When asked to indicate the extent to which effective governance in the health sector leads to

health gains by individuals and populations, 95% perceived that effective governance has either a

large or moderate effect on health status (See Figure 9 in Appendix).

13 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

The linkage between effective governance in sectors other than health and improved health of

individuals and the population

Respondents also linked the health of individuals and populations to effective governance in

other sectors. Approximately 93% of the respondents stated that effective governance in sectors

other than health leads to a large or moderate extent to better health of individuals and

populations (See Figure 10 in Appendix).

Relationships and interaction between leadership, management, and governance

The perception of the influence of leadership on governance and management is clear.

Leadership is perceived as pre-eminent among the three concepts and influencing the other two.

More than 90% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that; 1) leadership influences

governance, 2) leadership influences management, and 3) effective leadership is a pre-requisite

for effective governance (See Figure 11 in Appendix).

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis across gender, sectors (public, private, civil society), levels (local, state,

national and global), country where respondent works (non-OECD vs. OECD), geographical

region (Asia vs. Africa vs. Latin America and Caribbean), those who govern vs. those who

manage but don’t govern, and those who govern vs. those who lead but don’t govern was

performed to see if there are similarities and differences across these subgroups. A detailed

discussion of these can be found in the Appendix. The survey responses clearly had more

similarities than differences on most of the aspects of governing. Minor differences are

nevertheless interesting to note. For example, female respondents were more likely to perceive

‘inclusiveness’ and ‘oversight’ as significant elements of governing. This difference in

perception was statistically significant at 95% confidence level. There were no statistically

significant differences in the way male and female respondents defined hindrances in effective

governance for health, the exception being that women were more likely to identify poor

governance outside the sector of health and the political, historical, and cultural context as

significant impediments to effectively governing for health.

IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

Respondent demographics

Self-reported characteristics of the key informants (See Table 4) reveal a predominant

representation from the civil society and public sector. The informants represent 16 countries

form the three regions, i.e., Africa, Asia and Latin America. Africa has the strongest

representation among the informants. This was purposeful and by design. Two in every three of

the informants work at national level, 4% at local level and 12% in an institutional setting. Sixtyeight percent of the informants lead and govern, 20% lead and manage, and 12% lead but neither

govern nor manage. We found that our informants are a highly educated set of people. The

informants are likely to have multiple degrees and from multiple academic disciplines. Seventytwo percent (72%) of the informants have degrees in medicine or medical/surgical specialties,

56% have degrees in public health, 20% in other social sciences, 16% in management, and 16%

in other academic disciplines (one informant each with a degree in science, agriculture, law and

teaching). Medicine and public health combination predominates (44%) and is followed by

14 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

medicine and management (16%). Three respondents had medical degrees alone, and one had a

public health degree alone.

Differences in informant characteristics were noted by region. Overall, women informants

constituted 32% of all the informants. There were more men (7) than women (6) in the

informants from Africa. Women were under-represented in the informants from Latin America

and there were no women respondents from Asia.

Table 4: Participant demographics (n=25)

Characteristic

Gender

Female

Male

Sector

Civil Society

Private Sector

Government

Public Sector/Multi-Sector Governing Bodies

(Country Coordinating Mechanisms or CCMs)

Region

Latin America

Africa

Asia

Countries

Number (%) in each category

8 (32%)

17 (68%)

13 (52%)

1 (4%)

8 (32%)

3 (12%)

7 (28%) (5 Male and 2 Female)

13 (52%) (7 Male and 6 Female)

5 (20%) (5 Male)

Latin America [Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador,

Guatemala, Mexico, and Nicaragua (2)],

Africa [Kenya (8), Lesotho, Nigeria, Tanzania,

Uganda, and Zanzibar],

Asia [India (2), Lebanon, Oman, and Pakistan]

Language of the interview

English

18 (72%)

Spanish

7 (28%)

Levels where the respondents work

International

4 (16%)

National

17 (68%)

Local

1 (4%)

Institutional

3 (12%)

LMG composition

Those who lead and govern

17 (68%)

Those who lead and manage

5 (20%)

Those who lead

3 (12%)

Note: All categories are mutually exclusive and percentages add up to 100.

15 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

PARTICIPANT EXPERIENCES OF LEADING, GOVERNING AND

MANAGING

What is governance?

Many informants, in many different ways, indicated that governance is a process of making

decisions, and a process of assuring that decisions are implemented. One typical response was,

— “The two key ingredients of governance are, firstly, making a decision for a group of people

and then secondly, finding out whether it worked.” Through making these decisions,

expectations are defined and processes are determined by which an institution is run. Another

ingredient of the definition of governance according to many of the informants was its purpose

which they described as ‘to achieve results’ or ‘to achieve certain goals’ or ‘to accomplish a

vision’. Governance is the exercise of authority and has a political dimension to it. In the

political context, governance is also framed as a democracy issue. A number of informants stated

that governance goes hand-in-hand with leadership. Informants are aware that governance is a

generic term and it takes place in almost all sectors and at all levels — “when we talk about

governance in health, we must remember that we also have governance in agriculture, we have

governance in an environment, and so on.” Governance is done differently in private for-profit,

nonprofit, and public sectors. For example, there may be a collective responsibility to make a

governance decision as in a non-profit hospital board, while in the public sector it may be a

single person who governs; for example, a Minister of Health governs the Ministry of Health, or

it could be a collective body like the Cabinet of Ministers that governs.

Elements or practices of governance

Including the governed in the governing process emerged as a key practice of governing.

Listening to people, involving them in decision making, persuading them, being responsive to

their needs and issues, giving feedback to them, reconciling the different views and the different

positions, bringing together stakeholders/beneficiaries/customers/utilizers of service in the

governing process to achieve results was how the informants typically described this practice of

governing. Making sure that there are systems in place to ensure accountability, transparency and

community participation while governing was the most frequently voiced theme throughout the

interviews.

Collaboration across sectors (public, private for-profit and nonprofit) and ministries (ministry of

health and ministries other than health) and across levels (institutional, local, state, national and

international) was described as a key practice of governing. Several informants cited examples of

inter-sectoral and intra-sectoral collaboration involving several departments and ministries.

These collaborations resulted in successful health interventions and helped achieve the desired

health outcomes. Many respondents voiced the utility of having a forum where such

collaboration could take place on a regular basis. This would enhance the outreach to the

different sectors and levels, and to keep the collaborators interested in a task. This practice was

frequently mentioned in the context of the government or public sector governance.

Steering or policy-making was one of the most frequently voiced practices of governing. Policy

formulation was mentioned as an important element of the governance process. Many

informants stated this practice in terms of setting the big picture, setting up a direction for the

16 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

institution, and making policies in people’s interest based on evidence. Some informants stated

that they are using incentives to steer the health system in the desired direction.

Allocation emerged as one of the significant practices of governance. Smart resource allocation,

referred to by one informant as “distribution with logic” or placing money properly irrespective

of political gain, is perceived to be a part of the governance process. To allocate responsibility of

policy implementation and also authority and resources to carry out that responsibility effectively

was seen by many informants as a significant part of governing process. As with other practices,

the informants focused on the linkage of this practice with the end result. For example, one

informant said, — “prudent application of resources such that at the end we get the desired

results.” Resource mobilization for the organization was also mentioned as one key practice of

governance.

Oversight is another key element of the governance process that is carried out to assure

implementation. The informants clearly perceived the oversight role of the governing body or the

persons is ensuring that the management is doing what it needs to do to deliver the long term

strategy of the institution. Oversight by the leadership and the key actors within the government

health services was perceived as very critical in ensuring good governance principles within the

public health system. Informants felt that rewarding those who perform well and sanctioning

those who do not was part of governing. The need for financial oversight was highlighted by

many of the informants.

Regulation, a majority of the informants felt, was a significant element of governing process. To

formalize policies through laws, rules, regulations, protocols, standard operating procedures, or

resolutions appeared a recurring theme while discussing practices of governance. They saw this

practice as — “setting into motion transparent and credible processes which are difficult to

undermine.” A strong regulatory system based on merit and a strong capability to develop

standards - were both thought to lead to a situation where “politicians would have a lesser

influence.”

See Table 5 in the Appendix for themes and representative quotes on elements/practices of

governing.

Effective governance in the context of health

While defining effective governance in the context of health, the informants were fully aware of

its linkage with the quality of health services and health outcomes. The informants felt that

effective governance in the context of health is the governance that leads to both an improvement

in health service and the health of individuals and populations, and this impact is its defining

feature. “To achieve results” was probably the most common theme heard across all the domains

of this enquiry. Results achieved testify that the governance was effective. Transparency,

accountability and participation and inclusion were the predominant and recurring themes when

the informants discussed effective governance. Ethical and moral integrity, focus and vision, and

efficiency and equity were other important themes that emerged again and again in this context.

Table 6 below and Table 7 in the Appendix state the themes and representative quotes on

effective governance in the context of health. The informants gave many examples of effective

governance and many examples of poor governance from their experience which are described in

Table 8 in the Appendix. Deterrents and enablers of effective governance were broadly similar to

17 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

what we found through our quantitative survey. See Tables 9 and 10 in the Appendix for themes

and representative quotes on deterrents and enablers of effective governance.

Table 6: Effective governance: Predominant themes

Impact on health service and health of people

Transparency

Accountability

Participation

Inclusion

Ethical and Moral Integrity

Focus and Vision

Efficiency and Equity

Linkage between governance and health outcomes

Some informants felt that effective governance is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to

achieve good health for people. However, the majority of the informants expressed that

governance is critical for achieving good health outcomes for individuals and especially for

populations. They hinted at mechanisms through which governance translates into these good

health outcomes. As one informant said, —“we work better because the employees are more

motivated. They love their work and then of course a motivated and a happy worker works

better. The health workers come to work on time, they offer quality care and the patient outcome

is wonderful because these workers are available and that they give their best and the patients get

well.” Another noted, — “when you have poor governance in healthcare, it translates into less of

health promoting, health maintaining and disease prevention interventions within communities

and; when that happens, obviously the diseases that could potentially have been prevented

allowing communities to remain healthier for long, are not being prevented.”

The informants are cognizant of the influence of governance in the sectors other than health

sector on health outcomes. The impact of effective governance on health service and health is

perceived as its defining feature by the majority of the informants. The informants have indicated

that the effect of governance on health is mediated through its impact on health service or health

care in case of governance in health sector and through the social determinants of health in case

of governance in sectors other than health. The informants have described the impact of

governance on health service in terms of enhanced equity and access, effectiveness, efficiency,

affordability, sustainability, and timeliness. On the whole, the informants saw effective

governance as crucial to effective healthcare service delivery. See Table 11 in the Appendix for

themes and representative quotes on the linkage between governance and health outcomes.

Measuring governance

The informants suggested three ways to measure governance — measuring processes of effective

governance, measuring outcomes, and measuring long term impact (See Table 12 below). The

majority was in favor of measuring outcomes. Within the theme of measuring outcomes, there

were two sub themes — measuring attributes of health service, and measuring health outcomes

resulting from effective governance interventions. Many expressed that both the process and

outcomes should be measured. A minority of the informants felt that long term impact is a true

measure of effective governance. The informants substantiated what they said with concrete

examples of the measures (See Table 13 in Appendix).

18 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Table 12: Measuring governance: Themes and sub themes

Themes

Process

Outcomes

Both process and outcomes

Impact

Sub themes

Process

Health service attributes

Health outcomes

Process

Health service attributes

Health outcomes

Health impact

Impact beyond health

An overwhelming majority of the informants asserted that effective governance must be

measured by the result it has been able to produce in terms of improvement in health service and

the health of individuals and populations. A typical comment was, — “I think it is fundamental

to be able to show results.” There was a sole dissenting voice, — “does it [effective governance]

translate into good health? I’m not sure. Somebody has to show me conclusive evidence.”

Another informant underlined the importance of external evaluation of governance. Further, the

informants said that perspective of the measurer is a key in determining measures of governance.

See Table 13 in Appendix for themes and representative quotes on measuring governance.

Gender in governance

We examined the responses of the informants on gender in governance in four domains,

beginning with the gender issues related to women in boardrooms or governing positions, and

then increasingly broadening the scope of domains with gender issues related to women in health

workforce, and finally the issues related women as users of health care. The final domain of our

enquiry was what could be done on the issues surfaced by the informants. We adapted and used

the Rao Gupta (2000), Gupta et al. (2003) and IGWG (Caro 2009) defined gender approaches for

our analysis of the positions taken by the informants or the situations described by them.

1. Blind or gender neutral (gender does not influence how decisions are made)

2. Exploitative (maintains gender inequalities and stereotypes)

3. Accommodating (gender aware and accommodating but they do not seek to challenge the

status quo)

4. Responsive (clearly responsive to different needs based on gender)

5. Transformative (seek to transform gender relations and promote equity as a means of

achieving more sustainable health outcomes)

We received a range of informant responses from essentially gender blind to those seeking

gender transformation in different domains. Overall and on average, across all the domains we

found the perspective of 14 (56%) of our informants gender responsive, the perspective of 4

(16%) of our informants gender transformative, the perspective of 3 (12%) gender

accommodating, the perspective of 2 (8%) gender blind, and the perspective of 2 (8%) gender

exploitative. Those who expressed a gender exploitative perspective said things like — “gender

is culturally oriented. Culture is more important in the context of gender.” or “gender is context

dependent.” They appeared to be tolerant of maintaining gender inequalities or stereotypes if

culture defined them. The informants with gender blind perspective typically said, — “we would

also like competencies to be there as well” or “to me it doesn’t matter which gender one belongs

September 2011 – June 2012

19 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

to as long as they have the skills, the knowledge and the qualifications to be involved in any

aspect of health delivery.”

The gender responsive perspective was by far the predominant perspective narrated effectively in

the responses. The informants with gender transformative perspective advocated measures like

affirmative action, or special dispensation. The need for gender awareness, gender

responsiveness, and gender transformation in governance was heard from the overwhelming

majority of the informants. See Table 14 in the Appendix for representative quotes.

Inter-relationship and interaction of leadership, management and governance

Three themes clearly emerged from the responses of the 25 informants. First, leadership,

management and governance are interdependent, intricately linked, and reinforce each other. All

three roles interact in a balanced way to serve a purpose or to achieve a desired result. Second,

there is a clear overlap between the roles of leading, managing, and governing. Nevertheless,

each of the roles is relevant. Third, leaders are critical to the governing process. Effective

leadership is a prerequisite for effective governance and effective management. See Table 15 in

the Appendix for representative quotes.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the few surveys on perceptions and perspectives of the people

who lead, govern and manage in the heath sector and in health institutions in low and middle

income countries on governing and governance. We were able to collect and analyze

perspectives of 500 health leaders, managers and governors primarily from low and middle

income countries. There was a remarkable congruence between the findings of the qualitative

and quantitative components of our survey. We found from the respondents’ perspective,

leadership, management and governance are interdependent, intricately linked, and reinforce

each other. All three roles interact in a balanced way to serve a purpose or to achieve a result.

There is a clear overlap between the roles of leading, managing, and governing. Nevertheless,

each of the roles is relevant. Leaders are critical to the governing process, and effective

leadership is a prerequisite for effective governance and effective management.

Governance to our respondents is a process of making decisions, and a process of assuring that

decisions are implemented. For our respondents, governing has a purpose. Governance has

distinct political and technical dimensions. The respondents identified a clear set of governing

practices. Governing is steering and regulating for a purpose. Governing for our respondents is

raising and allocating resources and allocating responsibility for a purpose. Governing is

oversight. Governing is collaboration across settings and across sectors to achieve a purpose.

Governing, to them, is being inclusive.

Our informants defined effective governance in the context of health as the governance that leads

to both an improvement in health service and the health of individuals and populations. Other

defining features of effective governance our informants perceive are transparency,

accountability, participation, inclusion, ethical and moral integrity, focus and vision, and

efficiency and equity. Our informants have identified what impedes and what enables effective

20 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

governance in the context of health. We heard from them effective governance is a necessary but

not a sufficient condition to achieve good health for people. Nevertheless, it is critical for

achieving good health outcomes for individuals and especially for populations. The informants

are cognizant of the critical influence of governance in the sectors other than health sector, and

the social determinants of health on health outcomes. Our informants have experienced the

impact of governance in health sector on health service through enhanced equity and access,

effectiveness, efficiency, affordability, sustainability, and timeliness of the health service.

The informants suggested three ways to measure governance — measuring processes of effective

governance, measuring outcomes, and measuring long term impact. Measuring outcomes, i.e.

measuring attributes of health service, and measuring health impact resulting from effective

governance interventions was the recurring theme, and was preferred over measuring process

alone.

Our informants largely perceived governance in their settings basically as male dominated and

relegating women’s issues, i.e. issues faced by women in health work force and women as users

of service, to the background. The need for gender awareness, gender responsiveness, and gender

transformation in governance was heard from the overwhelming majority of the informants.

They suggested multiple ways in which gender could be integrated in governance such as

collecting disaggregated data; instituting a gender policy integrating gender perspectives in

health; increasing proportion of women in leadership and governance roles; establishing a

gender-sensitive implementation process that considers different needs of men and women;

establishing quotas and affirmative action coupled with empowerment measures; reinforcing a

safe, harassment free environment by upholding strict codes of conduct and zero tolerance for

discrimination; creating a comprehensive agenda to overcome discrimination and segregation;

and giving voice to all those affected by a policy.

Limitations

Quantitative survey

The low response rate of 8% is a limitation of the survey given that response rates to an internet

survey are typically in the range of 20-30%. The low response rate is partly explained by the fact

that the regularly contributing active membership of our universe of about 6,000 health sector

leaders is quite small. The active membership of the LeaderNet is approximately 10%, and the

Global Exchange Network for Reproductive Health was dormant for about a year prior to this

survey. The low response rate is also mitigated by the finding that 80% of those who responded

completed all of the questions in the survey. There are other limitations to the survey. First,

although the survey resulted in 477 responses from 80 countries and 5 continents, there is

inadequate representation of Asia in the survey responses. Second, the two on-line communities

of practice are supported by MSH and hence their members are familiar with the MSH’s

approach to leadership and management. Because MSH’s work in governance is newer and its

approach is still evolving, the survey responses on governing are unlikely to have been biased by

earlier familiarity with the MSH’s approach on the two constructs of leadership and

management. Finally, the responses are based on perceptions and opinions of practicing health

sector leaders and are not the findings of an experiment.

21 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

In-depth interviews

Our qualitative study has several limitations. Our participants may not be representative of all

those who lead, govern and manage the health sector or the health institutions of low and middle

income countries. With regard to gender, women are grossly under-represented in governing

positions in the international health context, whereas our study with 32% women respondents

may not be representative. Women may have been over-represented in our study. The study had

under-representation from the corporate and public sector, and over-representation form the civil

society sector. In addition, only 16 of about 150 low and middle income countries are

represented in the study. Those who lead, manage, and govern at state and local and institutional

levels are also under-represented.

Overall

The study results are perceptions and opinions and are not findings of a social experiment. The

researchers also had a bias in favor of the power of effective governance to achieve better health

outcomes, which may have influenced survey instruments and interpretation of results. In

addition, we did not explore the political dimension of governing in any substantive way. Our

exploration is largely technical. The study does not at all address the perspective of those who

are governed. These limitations should be considered when weighing the credibility of the

findings, the transferability of the lessons learned, and the scope and focus of future studies.

Policy Implications

This is one of the first studies of its kind in the international health setting and has important

implications for practice and policy in the context of resource-scarce and difficult-to-govern

environments of the low and middle income countries. The study findings have a potential to

inform the governance enhancement interventions in their health systems. Overall, the

governance improvement interventions suggested by the key informants fall within the following

areas: strengthening leadership and management; promoting integrity, measurement,

accountability, openness, transparency, participation, and gender responsiveness; and building

governance capacity.

The study contributes to defining in practical terms governing in the context of health. About

90% of the respondents defined governing in terms of inclusion and collaboration. This finding

tells us that the respondents are aware of the deterrents of effective governance and would

welcome support in these areas. Based on this study, the USAID-funded Leadership,

Management and Governance Project consortium partners have jointly identified practices of

effective governance (described in Table 16) that the project is using in its leadership,

management and governance enhancement work in the health sectors and the health institutions

of the low and middle income countries.

This study finds that the leadership, management and governance are intricately inter-linked and

reinforce each other. Effective leadership is a driver of change. A leadership, management or

governance intervention that considers this interaction and inter-relationship is more likely to be

effective. Leaders are the agents of change, and visionary and ethical leadership is the key in

22 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

enhancing governance. Leaders who govern in low and middle income countries and who wish

to achieve better health outcomes for their constituents should, according to their peers, consider

cultivating integrity, measurement, transparency, participation, accountability, gender

responsiveness, and using technology as they cultivate these attributes in their governing. The

international community in turn should support such leaders who are struggling to make a

difference in governance and through governance in health.

Table 16: Practices of effective governance identified in the USAID-funded Leadership,

Management and Governance Project

Governance practices Principles

Accountability

CULTIVATE

ACCOUNTABILITY Transparency

Legal, ethical

Foster a facilitative

and moral

decision-making

behavior

environment based on Accessibility

systems and structures Social justice

that support

Moral capital

transparency and

Oversight

accountability

Legitimacy

ENGAGE

STAKEHOLDERS

Identify, engage and

collaborate with

diverse stakeholders

representing the full

spectrum of interested

parties

Participation

Representation

Inclusion

Diversity

Gender equity

Conflict

resolution

23 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

Governing actions

1. Establish, champion, practice and enforce codes of

conduct that uphold the key governance principles

and demonstrate the legitimate authority of the

governance decision-making processes.

2. Embed accountability into the governing institutions

by creating mechanisms for the sharing of

information and by rewarding behaviors that

reinforce the key governance principles.

3. Make all reports on finances, activities, and plans

available to the public, and share them formally with

stakeholders, staff, public monitoring bodies, and the

media.

4. Set an expectation that other stakeholders share

similarly.

5. Establish oversight and review processes (internal

and external monitoring and evaluation by

committees; judicial board) to continuously assess

the impact and appropriateness of decisions made.

6. Establish a formal consultation mechanism (open

forums, special status at meetings, etc.) through

which constituencies may voice concerns or provide

other feedback.

7. Sustain a culture of integrity and openness that

serves the public interest.

1. Empower marginalized voices, including women, by

giving them a place in formal decision-making

structures.

2. Ensure appropriate participation of key stakeholders

through fair voting and decision-making procedures.

3. Create and maintain a safe space for the sharing of

ideas, so that genuine participation across diverse

stakeholder groups is feasible.

4. Provide an independent conflict resolution

mechanism accessible by all stakeholders and

interested parties.

5. Elicit, and respond to, all forms of feedback in a

timely manner.

6. Build coalitions and networks, where feasible and

September 2011 – June 2012

7.

SET SHARED

DIRECTION

Develop a collective

vision of the ‘ideal

state’ and a process

for designing an

action plan, with

measurable goals, for

reaching it

Stakeholder

alignment

Leadership

Management

Advocacy

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

STEWARD

RESOURCES

Steward resources

responsibly, building

capacity

Financial

Accountability

Development

Social

responsibility

Capacity

building

Country

ownership

Ethics

Resourcefulness

Efficiency

Effectiveness

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

24 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

necessary, and strive for consensus on achieving the

shared direction across all levels of governance.

Establish alliances for joint action at whole-ofgovernment and whole-of-society levels.

Oversee the process for developing and

implementing a shared action plan to achieve the

mission and vision of the governed (organization,

community, or country).

Advocate on behalf of stakeholders’ needs and

concerns, as identified through the formal

mechanisms above; making sure to include these in

defining the shared direction.

Document and disseminate the shared vision of the

‘ideal state.’

Oversee the process of setting goals to reach the

‘ideal state.’

Set up accountability mechanisms for achieving

goals that have been set, using defined indicators to

gauge progress toward goal achievement.

Advocate for the ‘ideal state’ in higher levels of

governance, other sectors outside of health, and other

convening venues with a role to play in its

realization.

Oversee the process of realization of the shared goals

and the desired outcomes.

Champion the acquisition and deployment of

resources to accomplish the organization’s mission

and plans.

Protect and invest wisely those resources entrusted in

the governing body to serve stakeholders and

beneficiaries.

Collect, analyze and use information and evidence

for making decisions on the use of resources,

including human, financial and technical resources,

and align resources in the health system and its

design with health system goals.

Determine, and execute, a strategy for building the

health sector’s capacity to absorb resources and

deliver services that are of high quality, appropriate

to the needs of the population, accessible, affordable,

and cost-effective in their consumption of scarce

resources.

Advocate for using resources in a way that

maximizes the health and well-being of the public

and the organization, and invest in communication

that puts health on the policy making agenda.

Inform and allow the public opportunities to monitor

raising, allocation, and use of resources, and

realization of the outcomes.

September 2011 – June 2012

References

Anello E. 2008. Elements of a framework for good governance in the public pharmaceutical

sector. In: A framework for good governance in the pharmaceutical sector. GGM model

framework. Working draft for field testing and revision. Geneva: World Health Organization

Department of Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical Policies, pp. 19-30. Online at:

http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/goodgovernance/GGMframework09.pdf, accessed 13

June 2012.

Azfar O, Kähkönen S, Meagher P. (2001). The Philippines: Consequences of Corruption. In:

Conditions for Effective Decentralized Governance: A Synthesis of Research Findings. IRIS

Center, University of Maryland, pp. 67-73.

Barr A, Lindelow M, Serneels P. 2009. Corruption in public service delivery: An experimental

analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), pp. 225-239.

Björkman M, Svensson J. 2009. Power to the People: Evidence from a Randomized Field

Experiment on Community-Based Monitoring in Uganda. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

124(2), pp. 735-769.

Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ. 2008. Health Governance: Concepts, Experience and Programming

Options. Submitted to the U.S. Agency for International Development. Washington, DC: Health

Systems 20/20.

Caro, D. 2009. The Gender Integration Continuum. In: A Manual for Integrating Gender Into

Reproductive Health and HIV Programs: From Commitment to Action. 2nd edn. Washington,

DC: The Interagency Gender Work Group (IGWG), pp. 9-18. Online at:

http://www.igwg.org/igwg_media/manualintegrgendr09_eng.pdf, accessed 13 June 2012.

Delavallade C. 2006. Corruption and distribution of public spending in developing countries.

Journal of Economics and Finance, 30(2), pp. 222-239.

Gupta GR, Whelan D, Allendorf, K. 2003. Integrating gender into HIV/AIDS programming and

policies. In: Integrating Gender into HIV/AIDS Programmes: A Review Paper. Geneva,

Switzerland: World Health Organization Department of Gender and Women’s Health, pp. 26-41.

Gupta S, Davoodi H, Tiongson E. 2001. Corruption and the provision of healthcare and

education services. In: Jain A (ed). The Political Economy of Corruption. 1st edn. London and

New York: Routeledge, pp. 111-141.

Kickbusch I, Gleicher, D. 2011. Smart governance for health and well-being. In: Governance for

health in the 21st century: a study conducted for the WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Copenhagen: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe, pp 43-68.

Lindelow M, Serneels P. 2006. The performance of health workers in Ethiopia: Results from

qualitative research. Social Science & Medicine, 62(9), pp. 2225-2235.

25 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Mikkelsen-Lopez I, Wyss K, De Savigny D. 2011. An approach to addressing governance from a

health system framework perspective. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 11(1), pp.

13.

Olafsdottir A, Reidpath D, Pokhrel S, Allotey P. 2011. Health systems performance in subSaharan Africa: governance, outcome and equity. BMC Public Health, 11(1), pp. 237.

Rajkumar AS, Swaroop V. 2008. Public spending and outcomes: Does governance matter?

Journal of Development Economics, 86(1), pp. 96-111.

Rao Gupta, G. 2000. Approaches for Empowering Women in the HIV/AIDS Pandemic: A

Gender Perspective. Paper presented at the Expert Group Meeting on The HIV/AIDS Pandemic

and Its Gender Implications, November 13–17, 2000. Windhoek, Namibia. New York: United

Nations Division for the Advancement of Women, World Health Organization (WHO), Joint

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Online at:

http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/csw/hivaids/Gupta.html, accessed 13 June 2012.

Reinhardt UE, Cheng T. 2000. The world health report 2000 - Health systems: improving

performance. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78(8), pp. 1064-1064.

Saltman RB, Ferroussier-Davis O. 2000. The concept of stewardship in health policy. Bulletin of

the World Health Organization, 78(6), pp. 732-739.

Siddiqi S, Masud TI, Nishtar S et al. 2009. Framework for assessing governance of the health

system in developing countries: Gateway to good governance. Health Policy, 90(1), pp. 13-25.

Smith PC, Anell A, Busse R et al. 2012. Leadership and governance in seven developed health

systems. Health Policy, 106(1), pp. 37-49.

Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems (SPS). 2011. Pharmaceuticals and the Public Interest:

The Importance of Good Governance. Submitted to the U.S. Agency for International

Development by the SPS Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health, pp. 7-16.

Veillard JHM, Brown AD, Bariş E, Permanand G, Klazinga NS. 2011. Health system

stewardship of National Health Ministries in the WHO European region: Concepts, functions and

assessment framework. Health Policy, 103(2–3), pp. 191-199.

26 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Appendix

FIGURES

27 L M G P r o j e c t Y e a r 1

September 2011 – June 2012

Conceptual Model of Governance for Health

Transparency

Accountability

Effective

utilization of

Measurement of

performance

Health Finances

Society

Better

health

outcomes

for the

society

Gender

Responsiveness

Use of

performance data

Human

Resources

Information

Use of evidence

Health Service

Medicines

Cultivate

accountability

Effective

Use of

technology

Effective

Management

Engage

stakeholders

Health

Leaders

Set shared

direction

Equitable

Efficient

Inclusion and

Participation

G

Trust and

Legitimacy