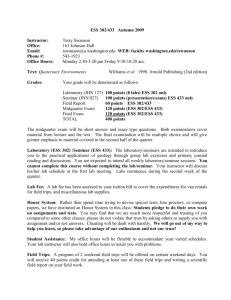

PowerPoint - The Institute of Public Administration of Canada

advertisement

Erin Edmundson Suzanne Gélinas Joanne Sullivan 7th Annual Conference of Public Administration Lord Nelson Hotel January 31, 2007 September 11, 2001, Flooding March 2003, Hurricane Juan, 2003, “White Juan”, 2004, Snowstorm Fall 2004. Introduction Definitions and Context What is Alternative Service Delivery? Why ASD in Nova Scotia Understanding the Contract: Emergency Response Benefits and Challenges Analysis: Application of ASD Literature Contrasting Models Conclusion Increased attention on disasters and emergencies – major concern for policy makers and citizens Nova Scotia: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Swissair, 1998 9/11, 2001 Hurricane Juan, 2003 “White Juan”, 2004 November Storm, November 2004 Disaster ◦ Disaster = Hazard + Vulnerability ◦ Policy Problem of “Global Scope” ◦ Affects ALL regions Poor or industrial Large or small Emergency Emergency Management ◦ “A present or imminent event…[that requires] prompt coordination of action or regulation of persons or property…to protect property or the health, safety or welfare of the people” ◦ Four Elements Mitigation Preparedness Recovery Response Utilized by all government coordinates in Canada Response, in recent years, to changing imperatives Literature attempts to define in practical terms Clear definition? ◦ TBS (1995, 2002) ◦ IPAC ◦ Ford and Zussman Alternative service delivery involves rethinking the roles and functions of government organizations to provide quality services, grounded in a strong policy foundation, to citizens through nontraditional means. <1998 social services delivered on Two Tier System 1998 DCS took over >Swissair – considered other options for ESS DCS considered competitive contracting But only one organization had interest, capacity, and Province-wide reach Canadian Red Cross Contract signed in March 2000 Little evidence of “government failure” DCS not unable to provide service Recognition that Red Cross had the necessary knowledge, resources and skills There are reasons to contract out social services Panet and Tribelcock: ◦ Non-profits: “better positioned to service community needs” “tend to be accountable…to the client population they service” Greater flexibility “to engage in experimentation and to tailor services innovatively” “community participation aspect” Provincial Jurisdiction for Emergencies: ◦ Contract for ESS involving 25+ people or 10+ units Across municipal boundaries Funding Duration Spatial Model of Disaster Alexander, S. (1993). Natural Disasters. New York: Chapman and Hall, p.1-40. As cited in: McAllister, I. (2006). Econ 5252, Module/Unit 7: Natural Disasters. Course Readings, Dalhousie University. Zone of Total Impact ◦ Immediate emergency, urgent threat ◦ Structures severely damaged, destroyed ◦ Mitigate injury Zone of Marginal Impact ◦ Damage less serious ◦ Municipal actors (police, firefighters, etc.). Zone of Filtration ◦ No physical damage ◦ Refugees in large numbers ◦ Red Cross contract! Assist DCS with plans for the provision of ESS Annual Report Policy and Operational Review Positively promote the Red Cross-DCS contract through media outlets Large, international organization Emergency Response Teams Strong volunteer base Significant training Benefits – DCS ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Lower caseload for employees in ESS Access to volunteers Clear roles and responsibilities for provision of ESS Alignment with international symbol Benefits – Red Cross ◦ Stable and predictable source of funding ◦ Increased visibility in NS ◦ Elevated responsibility – high performance standards ◦ Opened doors for acceptance at operation tables Challenges – DCS ◦ Loss of Control ◦ Loss of interest of volunteers due to few/no emergencies ◦ Volunteer turnover Challenges – Red Cross ◦ No significant challenges identified Contracts ◦ “Virtually all governments contract for services” (Savas, 70) ◦ Social-services usually provided by non-profit organization ◦ Savas (70) notes a number of conditions to make contracts feasible: Unambiguous specification of the work to be done The existence of a competitive climate The ability to monitor performance Enforceable and documented terms Roles and Responsibilities ◦ Defining worked “unambiguously” is difficult in ESS ◦ Contract outlines 5 responsibilities and what each means ◦ How, where, when is difficult to predict Evaluation and Results ◦ Great emphasis in literature on importance of evaluation and results Panet and Trebilcock Savas Aucoin ◦ Reporting essential for effective, efficient, equitable use of public resources ◦ Red Cross required: to provide DCS with an Annual Report on March 31 of every year that highlights ESS activities To conduct annual review with Minister with regard to policy and operations Value for Money and Focus on Outcomes ◦ Value for money not most important element of contract but still a factor Red Cross = volunteers v. DCS = overtime ◦ Focus on Outcomes more important Red Cross has a critical mass of knowledge and experience DCS measures outputs based on capacity to respond and actual response Shared Objectives and Common Goals ◦ DCS and Red Cross goals well aligned in ESS – to provide for the needs of citizens ◦ But contexts are necessarily different (Hall, Reed) ◦ Red Cross – organizational mandate to provide ESS ◦ Emergencies target specific clients (depending on situation) ◦ Equitable service public service value Loss of control ◦ Savas – Principle/Agent problem ◦ Concern of DCS – delegation of service provision to Red Cross Competitive Contracting ◦ Savas: “institutionalizes competition…encourages better performance” ◦ Australia: “can improve quality and foster innovation…achieve value for money outcomes and improve accountability and transparency” ◦ While in most cases competition is a best practice for ASD, it is often unavoidable ◦ DCS found that sole source contracting was unavoidable ◦ After consideration of competitive process, only one organization that had interest resources, knowledge, and geographic reach Employee Transition ◦ Often one of the most complicated issues when contracting for services ◦ DCS – no job loss to manage ◦ ESS not a full time job for most ◦ Public servants encouraged to volunteer Cost Comparison ◦ Often an important factor ◦ No cost comparison by DCS ◦ Difficult to determine cost-effectiveness in this case British Columbia ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Local authorities have jurisdiction (in-house) for ESS Provincial government assists Volunteers managed by government Different needs and concerns related to size, threats and vulnerabilities, and geographic location Government of British Columbia. Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. “About ESS”. Available [Online]: http://www.ess.bc.ca/about.htm Government of Canada ◦ May, 2006 PSEPC signed MOU with Red Cross ◦ Recognizes the relationship between organization with the goal to ensure emergency management is similar across Canada ◦ Not a legally binding guideline of roles and responsibilities Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada. 2006. Online: http://www.psepc.gc.ca/media/nr/2006/nr20060508-en.asp Benefits of this contract: ◦ Government betting from knowledge and resources ◦ Red Cross is able to pass on expertise and efficiency to tax payers – high standards of service Contract creates a formal relationship grounded in ASD best practices between two organizations committed to public service Precedent-setting model of ASD for other jurisdictions Brochures available Volunteer forms available to join the Red Cross Emergency Response Teams One meeting a month (2 hours) Lots of free training Lots of opportunity to make a difference in your community Aucoin, Peter. “Lesson 12: Collaborative Structures”, PUAD 5100 Lessons. Dalhousie University, 2005, 12.112.21 Boston, Jonathan. “Organizing for Service Delivery: Criteria and Opportunities”, B. Guy Peters and Donald J. Savoie (eds) Governance in the Twenty-first century. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000, 281331. Canada, Treasury Board Secretariat (1995). Framework for Alternative Program Delivery. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services. Available [Online]: http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/tbs-sct/tb_manualef/Pubs_pol/opepubs/TB_B4/dwnld/frdoce.doc Canada, Treasury Board Secretariat (2002). Policy on Alternative Service Delivery. Ottawa. Available [Online]: http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/asd-dmps/index_e.asp Canadian Red Cross. About the Red Cross. 2006. Available [Online]: http://www.redcross.ca/article.asp?id=000318&tid=019 November 21, 2006 Comfort, L., B. et al. “Reframing disaster policy: The global evolution of vulnerable communities.” Environmental Hazards, June 1999, 1:1, 39-44. Commonwealth of Australia. Department of Finance and Administration. “Competitive Tendering and Contracting Group”, Competitive Tendering and Contracting: Guidance for Managers, March 1998, 7-32. Dollery, Brian E. and Joe L. Wallis, “Chapter 7: Public Policy Toward the Voluntary Sector” The Political Economy of the Voluntary Sector: A Reappraisal of the Comparative Institutional Advantage of Voluntary Organizations Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 129-164. Ford, Robin and David Zussman, eds. 1997. Alternative Service Delivery: Sharing Governance in Canada. The Institute of Public Administration of Canada and KPMG Centre for Government Foundation. Government of Canada. Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada. Modernization of the Emergency Preparedness Act: Consultation Paper July2005. Available [Online]: http://www.psepc.gc.ca/pol/em/fl/Modernization_EPA.pdf Government of British Columbia. Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. “What do ESS volunteers do?” Available [Online]: http://www.ess.bc.ca/people.htm#what Government of the Province of Nova Scotia. Department of Community Services, Emergency Social Services Available [Online]: http://www.gov.ns.ca/coms/emergency_ss.html Government of the Province of Nova Scotia. Subsection 2 (b) Emergency Measures Act. 1990. Available [Online]: http://www.gov.ns.ca/legislature/legc/statutes/emergmsr.htm Hall, Michael H. and Paul B. Reed, “Shifting the burden: how much can government download to the non-profit sector?” Canadian Public Administration, Spring 2000, 41:1, 1-20. Kovacs, Paul and Howard Kunreuther, Managing Catastrophic Risk: Lessons From Canada Prepared for the ICLR/IBC Earthquake Conference March 23, 2001, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver. Available [Online]: http://opim.wharton.upenn.edu/risk/downloads/01-09-HK.pdf Langford, J.W. “Power Sharing in the Alternative Service Delivery World”. Ford, R. and Zussman, D. (Eds) Alternative Service Delivery: Sharing Governance in Canada. Toronto. Institute of Public Administration Canada. 1997, 59-70. Langille, Ancel. Red Cross Field Associate, Central District. Canadian Red Cross Email, November 24, 2006 Langille, Ancel 2006. Red Cross Field Associate, Central District. Canadian Red Cross. Personal Communication. Manuel, Barry. Presentation to Red Cross Emergency Response Team, Dartmouth Nova Scotia, November 14, 2006. Panet, Philip De L. and Michael J. Trebilcock, “Contracting-Out Social Services,” Canadian Public Administration,” Spring 2000, 41:1, 21-50. Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada. 2006. Online: http://www.psepc.gc.ca/media/nr/2006/nr20060508-en.asp Red Cross and Department of Community Services Agreement. 2000. Savas, E. S. “Alternative Arrangements for Providing Goods and Services” Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships New York: Chatham Home Publishers, 2000, 63-106. Savas, E. S. “Contracting for Public Services” Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships New York: Chatham Home Publishers, 2000, 174-210. State of Washington Department of Revenue. Excise Tax Advisory. January 28, 2006. http://dor.wa.gov/docs/rules/eta/2007r05.pdf November 9, 2006. United Nations. “Terminology” International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. Available [Online]: http://www.unisdr.org/eng/library/lib-terminology-eng%20home.htm Webb, John. Director, Nova Scotia Department of Community Services, Emergency Social Services Personal Communications, November 17, 2006. Williams, B. 2005. The Federal Charter of the American Red Cross. American Red Cross. Online http://www.redcross.org/museum/history/charter.asp Retrieved November