2NC - openCaselist 2013-2014

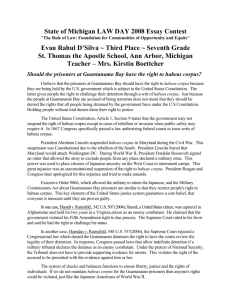

advertisement