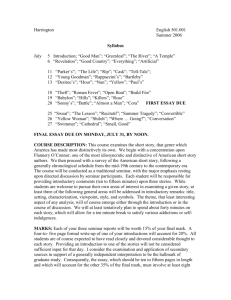

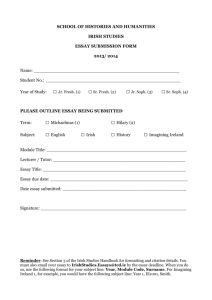

Introductory Reading - National University of Ireland, Galway

advertisement