WHITEPAPER-Crisis of..

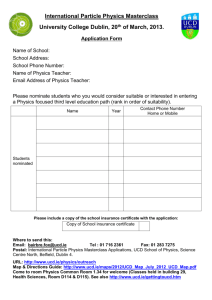

advertisement