DoGAF Prog Segments

FMC Program Segments 1900-1930

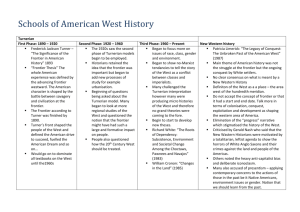

Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis

"...the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of

American history."

- Frederick Jackson Turner, 1893

BEN WATTENBERG: Let's start -- 1893, Chicago, our story of the first measured century begins at a world's fair, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus's arrival to what

Europeans called "The New World." For the 27 million visitors to the fair, it was a window to the near unimaginable changes to come in the next century. Like a giant department store where everything is bigger and better, the fair showcased the products of progress. There was the 22,000-pound block of cheese from Canada, and the world's largest cannon, measuring more than 43 feet in length, and weighing 132 tons from Germany. Measurement was in style. Numbers even defined standards of beauty. Scientists compiled the measurements of 40,000 college students. Artists used these statistics to create these statues of the "ideal man and woman." It was already clear that America would see the new century through data-colored glasses.

Just outside the fairground, one of the great promoters of the day,

William Cody, was staging a production of his own. Three times a day, Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show celebrated the derring-do of gunslinging cowboys and Indian warriors. For a new generation of

Americans, this is as close as they would ever come to the legendary experience of the American frontier.

While Buffalo Bill put tales of the heroic West on parade, a young professor came down to the world's fair with a new way to tell the same sort of story, but with data. Frederick Jackson Turner, from the fledgling University of Wisconsin, presented his thoughts to the

American Historical Association. His thesis would come to be called the single most influential piece of writing in the history of American history.

WILLIAM CRONON (Frederick Jackson Turner Professor of

History, University of Wisconsin): Turner starts this famous essay by quoting the Census Bureau, which interestingly in 1890 declares for the first time that there is no longer a visible frontier line on the demographic maps that the Census is producing. Up until that time, if you drew a map of where people were and were not living in the United States, and drew a line in areas that have more than two people per square mile or less than two people per square mile, there was a very clear demarcation between those two.

BEN WATTENBERG: From 1790 on, that line had been moving steadily Westward.

Thomas Jefferson had speculated that to fill the vast open spaces of America it would take a hundred generations. It took about 80 years. By 1890, people had settled throughout the Western territories and a clear frontier line could no longer be drawn.

WILLIAM CRONON: Turner sees those maps and says, Wait a second, something important is happening here -- something radical is changing in the nature of the

American experience. The frontier line is ending, and therefore the first chapter of

American history has come to a close.

BEN WATTENBERG: Turner believed that creating a nation out of the wilderness yielded character traits that were unique to Americans.

FREDERICK JACKSON TURNER (1893): "Coarseness and strength, acuteness and inquisitiveness, that restless, nervous energy, that dominant individualism that comes with freedom -- these are the traits of the frontier. This expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnishes the forces dominating American character." Frederick Jackson Turner, 1893.

WILLIAM CRONON: Turner grows up in this little town in central Wisconsin called

Portage, and he tells the story of that town as a kind of microcosm of this American melting pot that he thinks of as the frontier. You can't actually read the Turner frontier essay in 1893 without seeing that what he is really doing is taking the story of Portage,

Wisconsin, and mapping it onto the American map, so it becomes the story of all of

America.

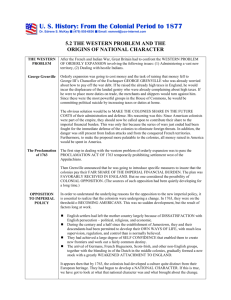

JOHN MILTON COOPER (Author, Pivotal Decades): Turner is picking up on an idea that is very much around -- a lot of people are commenting on it -- the frontier is closed. The country is industrializing. The place of the greatest growth, quite obviously, is in the cities. We are now becoming a country of cities and of bigger cities.

Immigrants are pouring in from Europe, and there is all this concern. What's happening to us? What are we becoming?

BEN WATTENBERG: Where now could the seed of liberty be planted? For Turner the frontier meant social and economic freedom, and he worried that with its closing

America would become more like Europe. Turner believed in what is now called

"American exceptionalism."

SEYMOUR MARTIN LIPSET (Author, American Exceptionalism): But his emphasis on the frontier was an emphasis on something which he thought was unique to the

United States, and therefore helping to explain why the United States was a more egalitarian society, why it was a more open society, and why there was more social mobility in it. And this in turn affected the class structure. And that makes Turner a social scientist, if you will, or closer to the ways in which social scientists operate.

BEN WATTENBERG: Turner is important for not just what he said about America, but for the way he told the story.

WILLIAM CRONON: Turner really is one of very first American historians who conceives of his intellectual activity as a social science. He really does think of history as a problem-solving activity, not a story-telling activity. And so he draws from all sorts of sciences, natural and social, that are going on around him. And maybe one of the biggest influences on Turner is geography. He is in love with maps, and the application of maps as a statistical tool, as a way not just of depicting information but of analyzing information, is the heart of what Turner is about.

BEN WATTENBERG: There was more information to analyze than ever before. The

1890 Census that so influenced Turner asked more questions than any other before that time -- or since. Measurement magnified the impact that the infant social sciences would have on American life. Data would be at the core of the first measured century.

WILLIAM CRONON: Turner is one of the new group of historians that emerges at the end of the 19th century, early 20th century, who are vocal advocates for something that they called "the new history." And that new history has a couple of characteristics.

One is it is far more committed than any prior body of historical scholarship to social science analysis. It tries to use statistics -- it uses the kind of data that historians had not used much up until that time in order to gain new insights and make new arguments. And then the other strand of the new history are those new insights, those new arguments, are pointed towards political interventions -- very explicit political interventions, to say history can make a difference to policy. It can change the way we govern this country by using data in new ways.

Photo Credits:

Col. W. F. Cody. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.