Abortion Laws in Australia Resource Sheet - Broadfield

advertisement

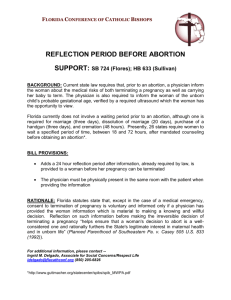

YEAR 11 LEGAL STUDIES NAME: ___________________ TUTOR GROUP: ____________ DATE: _____________ ABORTION LAWS IN AUSTRALIA Abortion is contained in criminal laws in all Australian states and territories except Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory. South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and the Northern Territory have legislation which sets out when abortion is or is not lawful. In Queensland and New South Wales, lawful abortion rests on common law interpretations of criminal laws, which results in unclear legality and confusion for both women and doctors. STATE/TERRITORY ACT VIC NSW AND QLD SA AND TAS WA NT ABORTION LAWS Legal, must be provided by medical doctor. Legal to 24 weeks. Legal post 24 weeks with two doctors’ approval. Abortion a crime for women and doctors. Legal when doctor believes a woman’s physical and/or mental health is in serious danger. In NSW social, economic and medical factors may be taken into account. Legal if two doctors agree that a woman’s physical and/or mental health endangered by pregnancy, or for serious foetal abnormality. Counselling compulsory in Tasmania. Unlawful abortion a crime. Legal up to 20 weeks, some restrictions particularly for under 16s. Very restricted after 20 weeks. Legal to 14 weeks if two doctors agree that woman’s physical and/or mental health endangered by pregnancy, or for serious foetal abnormality. Up to 23 weeks* in an emergency. QUEENSLAND The Legislation: In Queensland, abortion is a crime, although generally regarded as lawful if performed to prevent serious danger to the woman’s physical or mental health. Abortion is defined as unlawful in the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) under Sections 224, 225 & 226. Women can be criminally prosecuted for accessing abortion. Section 224. Any person who, with intent to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is or is not with child, unlawfully administers to her or causes her to take any poison or other noxious thing, or uses any force of any kind, or uses any other means whatever, is guilty of a crime, and is liable to imprisonment for 14 years. Section 225. Any woman who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, whether she is or is not with child, unlawfully administers to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or uses any force of any kind, or uses any other means whatever, or permits any such thing or means to be administered or used to her, is guilty of a crime, and is liable to imprisonment for 7 years. Section 226. Any person who unlawfully supplies to or procures for any person anything whatever, knowing that it is intended to be unlawfully used to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is or is not with child, is guilty of a misdemeanour, and is liable to imprisonment for 3 years. However, Section 282 of the Criminal Code attempts to define a lawful medical procedure, and while not relating specifically to abortion, would be used as a defence for doctors were they to be charged with unlawful abortion. Due to the R v Bayliss and Cullen court case (see below) in 1986 and the resulting judgement, an abortion is lawful in Queensland if carried out if there is serious danger to the woman’s physical and mental health from the continuance of the pregnancy. Case Law: R v Bayliss and Cullen In May 1985, the Queensland police under the Bjelke-Petersen government raided the Greenslopes Fertility Control Clinic which had opened in 1976 and had undergone political pressure since that time. Police interrogated women and took away 20,000 confidential patient files to be copied and studied. In June 1985, the Full Court ruled that the search warrants used by the police in the raid on the clinic were invalid, and ordered the files to be returned. The then Director of Prosecutions, Mr Des Sturgess, made a public plea for any person dissatisfied with the Greenslopes clinic to come forward. A 21-year-old mother of three children made a complaint about a termination of pregnancy performed in January 1985. As a result, Doctors Bayliss and Cullen were charged with procuring an illegal abortion contrary to Section 224 of the Criminal Code, and inflicting grievous bodily harm. The presiding judge at that trial R v Bayliss and Cullen (1986) was Judge McGuire. He based his ruling on the celebrated English case R v Bourne (1939) and a Victorian ruling by Justice Menhennit in R v Davidson (1969). Judge McGuire expressed the firm opinion that the R v Davidson case represents the law in Queensland with respect to Sections 224 and 282. The Criminal Code s 282 provides the accepted defence to a charge of unlawful abortion under s224. It would appear from the stance taken by Judge McGuire that a prosecution under s224 will fail unless the Crown can prove the abortion was not performed upon the unborn child “for the preservation of the mother’s life” and was not “reasonable having regard to the patient’s state at the time and to all the circumstances of the case”. Judge McGuire indicated that the present abortion law in Queensland was uncertain, and that more imperative authority, either the Court of Appeal or Parliament, would be required to effect changes to clarify the law. At the conclusion of the trial, Doctors Bayliss and Cullen were found not guilty on both counts. The basis for lawful abortion in Queensland currently rests on Judge McGuire’s decision. Since 1986, the law on abortion has not been tested as basically the prosecuting authorities have ‘turned a blind eye’. The Queensland Parliament has not acted to address Judge Maguire’s concern around the uncertainty of the law. Child Destruction Under section 313 (2), it is crime to unlawfully to assault a pregnant woman and destroy the life of, do grievous bodily harm to, or transmit a serious disease to, “the child” before its birth. The penalty for this new offence is life imprisonment. It is unclear whether section 313 (2) could be applied in the context of medical abortion. Arguably the word “unlawfully” in section 313 (2) would limit its application in that context to those medical abortions that are already prohibited under the Queensland provisions that make unlawful abortion a crime, and thus to abortions that do not satisfy the test in R v Bayliss and Cullen. Recent Developments in Queensland: The Cairns Case In April 2009, a 19-year-old Cairns woman was charged under section 225 in the Queensland Criminal Code, for procuring her own miscarriage. Her partner was charged under section 226 for assisting her. The case was heard in the Cairns District Court in October 2010, where the jury brought down not guilty verdicts in both charges. The court heard the couple arranged for a relative to send a supply of the drug misoprostol along with a variation of mifepristone, used in medical abortions, to Australia from the Ukraine. It was claimed the woman used the drug successfully to terminate her pregnancy at around 40 days, after the couple decided they were too young to parent, and that the couple made no inquiries about the availability of abortion in Cairns. The couple faced a combined 10 years’ imprisonment if convicted of the offences, which were been brought under the Criminal Code provisions relating to abortion. This was the first known time that a woman has been charged in Queensland for choosing an abortion. The charges caused two Cairns doctors providing medical abortion to cease doing so in June 2009, for fear their patients would be similarly targeted. This led to more doctors across the state following suit, including those doctors providing abortion within public hospitals. It was this withdrawal of public services, only offered to women seeking termination after a diagnosis of severe foetal abnormality, foetal death or maternal illness, which forced the Queensland Government to re-examine abortion law. Legislative Amendments: Changes to s282 of the Criminal Code Arising from the concerns of doctors and others due to the prosecution of a Cairns couple for allegedly procuring an abortion, the Queensland Government introduced changes to section 282 of the Criminal Code in September 2009. Section 282 of Queensland’s Criminal Code does not relate specifically to abortion, but provides a defence for doctors charged with performing a procedure unlawfully. It is the defence on which doctors would rely, were they charged over providing abortion. The old text of s282 is as follows: A person is not criminally responsible for performing in good faith and with reasonable care and skill a surgical operation upon any person for the patient’s benefit, or upon an unborn child for the preservation of the mother’s life, if the performance of the operation is reasonable, having regard to the patient’s state at the time and to all circumstances of the case. The concern of providers was that ‘surgical operation’ was specified, and that medical abortion could not really be defined as a surgical operation. This grey area existed for many years and was repeatedly raised as a concern by doctors. To resolve this issue, the Government committed to reforming this section of the Code to allow for the provision of medication - which they argued was also applicable to treatments such as chemotherapy. The revised section now reads: A person is not criminally responsible for performing or providing, in good faith and with reasonable care and skill a surgical operation on or medical treatment of: a) a person or unborn child for the patient’s benefit; or b) a person or unborn child to preserve the mother’s life; if performing the operation or providing the medical treatment is reasonable, having regard to the patient’s state at the time and to all circumstances of the case. There is also an added clause stating that if a person has been lawfully supplied (or believes they have been lawfully supplied) with a substance then it is legal for them to use it—thereby offering a small amount of protection to women seeking medical abortion. The sections pertaining specifically to abortion, s224-226, remain in the Code, and were not examined or altered in any way. They set out penalties for doctors, women and support people. NEW SOUTH WALES In NSW, abortion is generally regarded as lawful if performed to prevent serious danger to the woman’s mental and physical health, which includes economic and social pressures. In NSW abortion is in the Crimes Act 1900 (ss 82, 83 and 84) with penalties of up to 10 years imprisonment for the woman, the doctor and anyone who assists: Section 82. Whosoever, being a woman with child, unlawfully administers to herself any drug or noxious thing; or unlawfully uses any instrument to procure her miscarriage, shall be liable to penal servitude for ten years. Section 83. Whosoever unlawfully administers to, or causes to be taken by, any woman, whether with child or not, any drug or noxious thing; or unlawfully uses any instrument or other means, with intent in such cases to procure her miscarriage, shall be liable to penal servitude for ten years. Section 84. Whosoever unlawfully supplies or procures any drug or noxious thing, or any instrument or thing whatsoever, knowing that the same is intended to be unlawfully used with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman whether with child or not, shall be liable to penal servitude for life. The Crimes Act specifies that abortion is a crime only if it is performed unlawfully. However, it does not define when an abortion would be considered lawful or unlawful. To clarify the situation, Judge Levine in 1971 established a legal precedent in his ruling on the definition of lawful. He allowed that an abortion should be considered to be lawful if the doctor honestly believes on reasonable grounds that “the operation was necessary to preserve the woman involved from serious danger to her life or physical or mental health which the continuance of the pregnancy would entail” and that in regard to mental health the doctor may take into account “the effects of economic or social stress that may be pertaining to the time”. Levine also specified that two doctors’ opinions are not necessary and that the abortion does not have to be performed in public hospital. The Levine judgement has been affirmed and followed by the courts in New South Wales. Since 1973 there has been no prosecution for an unlawful abortion. Important points summarised: Abortion is not always unlawful in NSW The test for unlawfulness of abortion is whether a doctor honestly believes on reasonable grounds that the abortion is necessary to preserve the woman from serious danger to her life or physical or mental health. Mental health has been interpreted as including the effects of economic or social stress that may pertain at the time. In NSW you do not need a referral to go to a clinic for an abortion. You can call them directly. WESTERN AUSTRALIA In Western Australia, provisions relating to abortion are found in the Criminal Code and the Health Act. The Acts Amendment (Abortion) Act 1998 repealed four sections of the Criminal Code and enacted a new section 199 and placed regulations in the Health Act. Criminal Code S199 Abortion must be performed by a medical practitioner in good faith, and with reasonable care and skill. Abortion must be justified under Section 334 of the Health Act 1911. Where an abortion is unlawfully performed by a medical practitioner he or she is liable to a fine of $50000. Where an abortion is unlawfully performed by someone other than a medical practitioner, the penalty is a maximum of five years imprisonment. The offence of ‘unlawful’ abortion may only be committed by the persons involved in performing the abortion. The patient herself is not subject to any legal sanction in Western Australia. Section 259 is a defence for unlawful abortion: A person is not criminally responsible for administering, in good faith and with reasonable care and skill, surgical or medical treatment – (a) to another person for that other person’s benefit; or (b) to an unborn child for the preservation of the mother’s life, if the administration of the treatment is reasonable, having regards to the patient’s state at the time and to all the circumstances of the case. The Health Act (Abortion) Amendment Act 1998 details when the performance of abortion is justified in Section 334 (3) : (a) the woman concerned has given informed consent; or (b) the woman concerned will suffer serious personal, family or social consequences if the abortion is not performed; or (c) serious danger to the physical or mental health of the woman concerned will result if the abortion is not performed; or (d) the pregnancy of the woman concerned is causing serious danger to her physical or mental health. Informed consent means a medical practitioner other than the one performing the abortion has provided or offered or referred the woman to counselling. Proof of consent is not defined so the Royal College of General Practitioners has prepared an information package and consent forms for doctors. After 20 weeks of pregnancy, two medical practitioners from a panel of six appointed by the Minister have to agree that the mother or unborn child has a severe medical condition. These abortions can only be performed at a facility approved by the Minister. (Section 7) No person, hospital, health institution, or other institution or service is under a duty where by contract or by statutory or other legal requirement to participate in the performance of an abortion. (Section 334 (2)) Dependent minors (girls under 16 years who are supported by at least one parent) need to have one parent informed, and given the opportunity to participate in counselling before an abortion can be performed. However she may apply to the Children’s Court for an order to proceed with an abortion if it is not considered suitable to involve the parents(s). Section 335 of the Health Act is amended to: Require medical practitioners to notify the Health Department within fourteen days of an abortion being performed. The prescribed form must not contain particulars from which it may be possible to ascertain the identity of the patient. Review of provisions relating to abortion must be carried out after three years with the Minister reporting to Parliament within four years of commencement of the Act. SOUTH AUSTRALIA In South Australia, the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (amended in 1969) Sections 81(1), 81 (2) and 82 outline the penalties for unlawful abortion. Section 82 (A) outlines the circumstances in which a lawful abortion may be obtained. For an abortion to be legal, it must be carried out within 28 weeks of conception in a prescribed hospital by a legally qualified medical practitioner, provided he or she is of the opinion, formed in good faith, that either the “maternal health” ground or the “foetal disability” ground is satisfied. The “maternal health” ground permits abortion if more risk to the pregnant woman’s life, or to her physical or mental health (taking into account her actual of reasonably foreseeable environment), would be posed by continuing rather than terminating the pregnancy. Section 82A(1)(a)(i). The “foetal disability” ground permits abortion if there is a substantial risk that the child would be seriously physically or mentally handicapped if the pregnancy were not terminated and the child were born. A second qualified medical practitioner must share the medical practitioner’s opinion that either of these grounds is satisfied. Section 82A(1)(a). The wording of the “maternal health” ground suggests a liberality of access to abortion in early pregnancy. A conscience clause, Section 82A(5), enables medical practitioners to elect not to participate in an abortion. The pregnant woman must have been resident in South Australia for at least two months before the abortion. Section 82A(2). VICTORIA In October 2008, based on the report of the Victorian Law Review Commission, the Victorian parliament passed new legislation - Abortion Law Reform Bill 2008. R v Davidson In the Victorian case R v Davidson (1969), Justice Menhennitt defined the meaning of “unlawful” as it appears in Section 65 of the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic.) by reference to what is lawful. He settled on the principle of “necessity” which provides that an act which would usually be a crime can be excused if: It was done to avoid otherwise inevitable consequences The consequences would have inflicted irreparable evil That no more was done than was reasonably necessary That the evil inflicted by the act was not disproportionate to the evil avoided This principle contains two elements, one of necessity and one of proportion, which require that a pregnancy poses a certain danger to a woman’s health before its termination will be lawful. Menhennitt J. detailed the circumstances in which an abortion could be lawfully performed. The accused must have honestly believed on reasonable grounds that the act done by him was: necessary to preserve the woman from a serious danger to her life or physical or mental health (not being merely the normal dangers of pregnancy and childbirth) which the continuance of pregnancy would entail in the circumstances not out of proportion to the danger to be averted. For abortion to be unlawful the prosecution has to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the medical practitioner lacked this honest belief. The Menhennitt judgement was important because it included, for the first time in Australia, both mental and physical health risks as grounds for an abortion. TASMANIA Laws relating to abortion are contained within the Tasmanian Criminal Code. The sections relating to abortion were amended in December 2001. Abortion is lawful on the basis that two medical practitioners agree that the continuation of the pregnancy would involve greater risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman than if the pregnancy were terminated. 134 (1) Any woman who, being pregnant, unlawfully administers to herself, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, any poison or other noxious thing or with such intent unlawfully uses any instrument or other means whatsoever, is guilty of a crime. (2) [Section 134 Amended by No. 123 of 2001, s. 4, Applied:24 Dec 2001] Any person who, with intent to procure the miscarriage of a woman, unlawfully administers to her, or causes her to take, any poison or other noxious thing, or with such intent unlawfully uses any instrument or other means whatsoever, is guilty of a crime. Charge: Administering poison [or using means] to procure abortion. Aiding in intended abortion. 135. [Section 135 Amended by No. 123 of 2001, s. 4, Applied:24 Dec 2001] Any person who unlawfully supplies to or procures for any other person anything whatever, knowing that it is intended to be unlawfully used with intent to procure the miscarriage of a woman, is guilty of a crime. Medical termination of pregnancy 164. [Section 164 Repealed by No. 13 of 1957, s. 3 ][Section 164 Amended by No. 123 of 2001, s. 4, Applied:24 Dec 2001] (1) Notwithstanding anything contained in section 134, 135 or 165, but subject to this section, a person is not guilty of a crime in relation to the termination of a pregnancy which is legally justified. (2) The termination of a pregnancy is legally justified if: (a) two registered medical practitioners have certified, in writing, that the continuation of the pregnancy would involve greater risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman than if the pregnancy were terminated; and (b) the woman has given informed consent unless it is impracticable for her to do so. (3) In assessing the risk referred to in subsection (2), the registered medical practitioners may take account of any matter which they consider to be relevant. (4) If it is impracticable for the woman to give informed consent, the two registered medical practitioners referred to in subsection (2)(a) are to make a declaration in writing detailing the reasons why it was impracticable for the woman to give informed consent. (5) At least one of the registered medical practitioners referred to in subsection (2)(a) is to specialise in obstetrics or gynaecology. (6) A legally justified termination can only be performed by a registered medical practitioner. (7) Subject to subsection (8), no person is under a duty, whether by contract or by any statutory or other legal requirement, to participate in any treatment, including any counselling authorised by this section, to which the person has a conscientious objection. (8) Nothing in subsection (7) affects any duty to participate in treatment which is necessary to save the life of a pregnant woman or to prevent her immediate serious physical injury. (9) In this section, "woman" means any female person of any age, and "informed consent" means consent given by a woman where: (a) a registered medical practitioner has provided her with counselling about the medical risk of termination of pregnancy and of carrying a pregnancy to term; and (b) a registered medical practitioner has referred her to counselling about other matters relating to termination of pregnancy and carrying a pregnancy to term; AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY There are no laws making specific reference to abortion within the ACT Crimes Act. The Medical Practitioners (Maternal Health) Amendment Act 2002: Only a registered medical practitioner may carry out abortion (Maximum penalty – 5 years imprisonment) Abortion is to carried out in a medical facility, or part of a medical facility (Maximum penalty – 50 penalty points, 6 months imprisonment or both). Ministerial approval is required for the medical facility, or part of, for abortions to be performed. No person is required to assist or perform in the carrying out of abortion. NORTHERN TERRITORY Services for termination of pregnancy are legally available in the Northern Territory up to 14 weeks gestation where either the “maternal health ground” or the “foetal disability ground” is satisfied. The legislation requires an abortion at this stage of pregnancy to be carried out in a hospital, by a gynaecologist or obstetrician. A second doctor must share the opinion that either of the grounds is satisfied. Abortion in the Northern Territory is governed by the Criminal Code Act 1983 Sections 172, 173, 174. Section 172 sets out when termination of pregnancy is against the law: Subject to s. 174, any person who, with the intention of procuring the miscarriage of a woman or girl, whether or not the woman or girl is pregnant, administers to her, or causes to be taken by her, a poison or other noxious thing, or uses an instrument or other means, is guilty of a crime and is liable to imprisonment for seven years. Section 173 outlaws aiding and abetting the procurement of abortion. Section 174(1) outlines specific circumstances in which abortion is legal. It is lawful: (a) for a medical practitioner who is a gynaecologist or obstetrician to give medical treatment with the intention of procuring the miscarriage of a woman or girl who, he has reasonable cause to believe after medically examining her, has been pregnant for not more than 14 weeks if the medical treatment is given in hospital and the medical practitioner and another medical practitioner are of the opinion, formed in good faith after medical examination of the woman or girl by them, that (i) the continuance of the pregnancy would involve greater risk to her life or greater risk of injury to her physical or mental health than if the pregnancy were terminated; or (ii) there is a substantial risk that, if the pregnancy were not terminated and the child were to be born, the child would have or suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped; (b) for a medical practitioner to give medical treatment with the intention of procuring the miscarriage of a woman or girl who, he has reasonable cause to believe after medically examining her, has been pregnant for not more than 23 weeks is the medical practitioner is of the opinion formed in good faith after his medical examination of her, that termination of the pregnancy is immediately necessary to prevent grave injury to her physical or mental health; or (c) for a medical practitioner to give medical treatment with the intention of procuring the miscarriage of a woman or girl if the treatment is given in good faith for the purpose only of preserving her life. Section 174 (2), (3) and (4) provide that a person with a conscientious objection to abortion is not under a duty to assist in the operation or disposal of an aborted foetus, the burden of proving the objection lying on the person claiming it; that a medical practitioner continues to have a duty to obtain the consent of the person undergoing the abortion operation, and it must be done with professional care and in accordance with the law; and that where a girl is under 16 years old, consent must be obtained from “each person having authority in law … to give the consent”. Any medical practitioner may lawfully terminate a pregnancy of up to 23 weeks if the doctor believes in good faith that it is immediately necessary to prevent grave injury to the pregnant woman’s physical or mental health. Any medical practitioner may lawfully terminate a pregnancy at any stage of pregnancy if the doctor believes in good faith that it is for the purpose only of preserving the pregnant woman’s life.