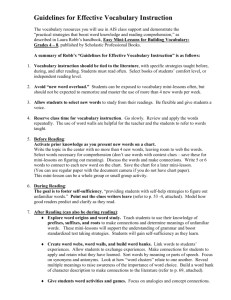

“Final” Requirements for First-Quarter Grades

advertisement

Chapter 2: Daily Success in the Workshop “Creativity can be taught.” – James C. Kaufman, professor at California State University, San Bernardino (Whoever he is…)1 *** I describe teaching through a surfing metaphor: You get up on the wave the first day, find your balance, stay on your feet, and ride it all the way to the shore. The writing workshop is effective because it puts structures in place that help you get up on the wave and stay on top from early September to late June. Many key structures are explained in a handout given during the first week of each quarter: “Goals & Deadlines.” This handout tells the students exactly what they will need to accomplish by exactly what date. On the back is a chart for students to keep track of their submissions. When students enter your workshop on Day Two, coach them to arrange their chairs properly, open their notebooks, and take out their writing tools. When they are settled, prepared, and ready to listen, distribute the “Goals & Deadlines” handout and read every word of it aloud. Review the handout on the next two pages; further explanation follows. 1 As qtd. in the July 19, 2010 issue of Newsweek. Creative Writing Fall, 2011 Goals & Deadlines – 1st Quarter Important First-Quarter Dates Mon. 9/13 Mon. 9/20 Fri. 10/8 Wed. 11/3 Mon. 11/8 Wed. 11/10 Mon. 11/15 Summer Reading Exam & Materials Check-date Creative writing submissions accepted Interim reports are due Last day to submit new creative writing FIRST-QUARTER EXAM Final deadline for all rewrites Last official day of marking period “Final” Requirements for First-Quarter Grades 90+ 7 poems of any style 4 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 3 mind maps or other artistic piece 90 or higher on quarterly exam (suggested) 80+ 6 poems of any style 3 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 2 mind maps or other artistic piece 80 or higher on quarterly exam (suggested) 70+ 5 poems of any style 2 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 1 mind maps or other artistic piece 70 or higher on quarterly exam (suggested) 65 4 poems of any style 2 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 1 mind maps or other artistic piece 65 or higher on quarterly exam (suggested) Class Participation: This is an important factor in determining your quarterly average. o o Positive class participation: working on writing, coming prepared, keeping a folder, keeping a notebook, staying on task. Negative class participation: Doing work for another class, having your cell phone ring, textmessaging in class, stepping outside to make or take a phone call, sleeping, coming unprepared for class, coming tardy, being frequently absent. Keep Track of Your Submissions Directions: Use this form to stay on top of your deadlines. Mark down your pieces as you submit them, and note its genre (poetry, memoir, mind-map, etc.), who edited the material, and what stage the piece is in (t-e, final). Date Title Genre Editor(s) T-E or Final 9/1 “Sample Entry” Free-verse poem Jim Daszenski, Jen Hastings t-e Breaking Down the “Goals & Deadlines” Handout Distribute this sheet on the second day of school, printed on colored paper. Put administrative-type handouts like these on color for stronger emphasis. And, it’s easier to say to students, “Take out that green handout from the first week.” Some background information on “Goals & Deadlines”: The Deadlines. Get all of the important dates in front of the class as early as possible. “Take out your plan-books,” I’ll say to the class. “Put these dates in your plan-books right now!” Be careful when planning these deadlines. Give yourself several days at the end of a marking period when the grading crush is its heaviest. You must be strict with the deadlines! Do not accept submissions after the due dates.2 o The Materials Check-Date. The summer reading exam is a departmental formality that must be incorporated into the curriculum. While the kids are writing their essays, circulate around the room making notes on who does and who does not have the mandatory materials (spiral notebook, set of markers, twosided folder). o The first day to submit creative writing is usually 8-10 class sessions after school starts. Build in time to pump your classes full of the basic mini-lessons, coach them through a few writing workshops, and wait until they can submit writing that has had time to cook. 2 It is a definitive failure if you give students eight weeks to accomplish their goals, and they still have to turn in work after the deadline. It’s okay to tell a student he or she failed at the task – especially if the course isn’t over yet and there’s another marking period remaining. Just be honest and encouraging: “I’m sorry, Rita. I wish you had made your deadlines. The fact that you are trying to submit work after the deadline means you didn’t earn a passing classwork grade. Hold onto that, polish it up, and turn it in next week to start the next quarter off on the right foot.” The design of that statement – I’m sorry I have to do this, but it’s the consequence for your actions – comes from a terrific book called Leader Effectiveness Training L.E.T.: The Proven People Skills for Tomorrow’s Leaders Today by Thomas Gordon. o It’s important to remind students of the date progress reports are due. If you don’t give tests and homework to manufacture a numerical grade, you can only evaluate students on a couple of criteria: behavior, attendance, and writing submitted. Let them know this and encourage them to, “Give me a reason to say something nice on the progress report.” o The “last day to submit new creative writing” is the deadline for turning in a new piece. After this day, all submissions must be red-inked and have a “teacheredit” label at the top. o The first-quarter test is on everything they have learned in the class. It can be “open-book” and allow students to use their notes and handouts. o The “last day to submit all rewrites” is the final day to accept any submission. Make announcements throughout the course like, “There are only three days left to get me revisions and score points for your first-quarter classwork grade.” o Let them know the “last official day of the marking period” just in case you want to be lenient with a student who has extenuating circumstances or is struggling to get a 65, pass the class, or graduate high school. The goals. It is important that students choose their own topics to write about; yet, it is equally important to push them in different directions and force them to experiment with a variety of genres. Essentially, have students compose poetry, write prose, and create mind maps. Let’s analyze the requirements for a 90+: o “7 Poems of any style” means that students need to get 7 poems marked “final” before the deadline. Write “any style” here because it doesn’t matter if they write them in couplets, quatrains, or free verse. It doesn’t matter if they make found poems, list poems, or A-to-Z poems. The mini-lessons teach them about the tools, techniques, and types of poems – it’s up to each student to determine the make-up of each piece. Try to help by pointing out weaknesses, making suggestions, and correcting mistakes. Encourage them to experiment with the class lessons and coach them through the process. “This poem feels like it’s dying for rhyming quatrains,” you might tell a student. Or, “This piece would be great as free verse. Trying to rhyme is side-tracking a powerful idea. Kill the rhymes; create stanzas with purpose, and amp up the bloody pebbles.” o “4 pages of memoir” means that students have choices in their prose submissions: They can write one four-page tale or two two-page stories. They can turn in four one-page anecdotes or eight half-page short-shorts. It doesn’t matter! They just have to accomplish the goal of four “final” pages of prose by the deadline. Giving them such wide-open choices – they can write college essays, memoirs, newspaper articles, or most anything else3 – is twofold in benefit: 1) They are quite appreciative of the flexibility to deliver their art, their way. Encourage seniors to write their college essays in your workshop and submit them as pages of prose. My mini-lesson entitled “College Essays” teaches them the fundamentals of the genre and I distribute Pupils may not write assignments for other classes in the writing workshop. They know this, yet you’ll see it every year. 3 Question: What do you do if you see a boy doing math homework in the writing workshop, you ask him to stop, and he politely refuses or totally ignores you? Answer: Don’t make a big scene. In fact, just observe the behavior and avoid confrontation. The next day, speak to him before class or in private: “I understand you really had to get your math done yesterday. But, let’s see a better effort at writing today.” Make note of the infraction in case it is part of pattern or merits a deduction of classparticipation points. *This approach comes from Professor Aaron Lipton at SUNY-Stony Brook. His mantra is a great one: “Always be sympathetic to the student.” several samples. When I evaluate the prose, I usually write something like “2 ¾ pages of memoir/FINAL” across the top of the submission. 2) You have more interesting writing to work with. The prose that comes out of writer’s workshop is unique, experimental, and a pleasure to read and edit. The last thing any English teacher wants to read is a pile of 28 essays designed to sound, look, and think the same. That’s why it’s a dreadful task to grade standardized writing tests. o “3 mind maps or other artistic pieces” means students have to be thinking about aesthetics. Most students understand when I say, “I don’t like linear, Cornell Notes. 1-2-3, a-b-c, it doesn’t do it for me.” I prefer to take notes and brainstorm by webbing, by using colorful markers, and by having fun with it.4 The “Mind Mapping” mini-lesson includes showing the class at least 50 full-color awesome mind maps on original ideas like Elementary School Video Games, Korean Memories, or Camp Crestwood. These were all done by former students5. “Other artistic pieces” is included here because teaching students about mind maps will inspire them to other creative pursuits. It could be high-tech art with computers and video-cameras or low-tech art with scissors and magazines; incorporate it into the workshop, the rubric, and the curriculum. Encourage your learners to execute their visions. “As long as language is a part of it,” you say. 4 5 Could I be more Fish! Philosophy? I encourage you to make a strong habit out of collecting student samples in every genre you teach and of every essay you demand. They are invaluable teaching tools. My mini-lessons will show you how important student samples are in my writing workshop. I also keep folders of examples – college essays, mind maps, photo collages, etc. – and make them accessible to my students at all times. Collecting student samples is a priority in my teaching practice and is discussed more in depth in chapter four. o “90 or higher on the quarterly exam (suggested) – This is the suggested score because the quarterly grade = the average of the classwork grade and the test grade to determine the quarter grade. Remind them frequently of the importance of this test. Class-participation reminder. Put this on the bottom because repetition is a very powerful teaching tool. “Bill Nye the Science Guy” illustrated this perfectly; he would repeat an idea, term, or complex concept many times during an episode. Effective teachers will utilize the same technique – throughout a class period and throughout an entire course. The Back of the Handout I have to hand it to the resource-room teachers for demonstrating that organization is a powerful learning device. Charts like these help maintain organization.6 You could collect it at the end of the marking period, too. “Keep track of your own submissions in case I make a mistake in my notebook. Save all your submissions after I return them, too!” you can remind them. Every year a few students will save this sheet – torn, tattered, and filled out – and put it in their portfolios. 6 Educational strategies that are effective with resource-room students are going to be effective with any student. Frequently Asked Questions about “Goals & Deadlines” Q: What if students meet some of the requirements for a 90+, but not all of them? A: All goals must be met in order to achieve the grade. Here’s a look at a typical conversation on this topic. “What if I have three mind maps, four pages of memoir, and only six poems?” “Susan, how many poems do you need for an ‘A’?” “Seven.” “Is six seven?” “(silent confusion)” “Six is not seven, right? Therefore you can’t get a 90 if you only complete seven poems. Those accomplishments will probably get you an 88. You need to hit your goals to get the grade you want. Less than the goal is less than the grade.” “What if I do five pages of memoir but only six poems? “That could work. We could substitute one page of memoir for one poem.” *** Q: What if students want to write in genres other than memoir, poetry, and mind-maps? A: Encourage students to be enterprising and to tell you if they have writing ideas that fall outside of the rubric. What if they want to write and perform a song? Or create a video? What if they don’t even want to write poetry and want to write just memoirs? Do what you can to help them achieve their goals and discuss how their ideas will work with your grade-goals rubric before any writing is done. Avoid surprising the student with a bad grade at the end. An easy solution is to say, “one poem = one page.” However, the opposite isn’t true – nobody can write only poetry. It is important that students write real, authentic prose in the workshop. The bottom line here is flexibility and openness. You might say a video = a mind map. Or, an in-class performance means you get two “finals” for the song. An example conversation: “Mr. W, I want to write my autobiography about dealing with my epilepsy.” “That sounds awesome! Tell me what you have in mind, Jen.” “I already scribbled these notes for chapter one.” “OK, this is a big undertaking. Forget about writing poems for a while – let’s just focus on getting chapter one done. These notes look fascinating! Turn them into the first draft of the first chapter and we can go from there. Figure you’re going to need a minimum of 11 pages of memoir to get a 90+ because the seven poems can instead be seven pages of prose.” “Great! I’ve wanted to write this book all my life.” “Awesome! And, turn those notes into great-looking mind maps – they will help you brainstorm ideas and stay organized, plus I can count them towards your grade.” “Man, I love this class! Every class should be like this.” *** Q: Can students write fiction? A: Yes, but I hope they don’t. At this point in my career I’ve taught about 2,500 students. I swear on my life that the following fact is true: only three of them could write some decent fiction. Students this age, in this setting, can draw on their own lives to write beautiful, moving pieces of nonfiction. But when they turn their attention to storytelling, it comes out as uninspired, cliché-driven poppycock.7 7 I can’t imagine how painful it must be to read elementary-school fiction. Zero mini-lessons teach fiction because there is something horrendous about 99.9% of all student-written fiction, and if you’ve ever read any then you know exactly what I’m talking about. However, I will accept fiction and I will certainly work with youngsters who want to pursue fiction-writing. After all, I never say “No!” to a student with ideas. Here’s a realistic look at what this conversation sounds like: “Mr. Weinstein, can I write a murder mystery?” “You mean fiction!?” “Yeah, fiction.” “If you really want to, go ahead and pursue it. I will do my best to read and edit it and help you along the way. But, I don’t really teach fiction writing because studentfiction is usually painful to read. So, here’s a warning – I will give it a shot and try to edit it, but if it is painful for me to read then I’m going to stop reading it in the middle and move on to the rest of my work.” “Really!?” “Yeah, really – and I won’t read it again. So, if it’s got to be fiction, it’s got to be very good.” “Ya’ know what, Weinstein? I’m gonna knock your socks off with it.” “I’ll believe it when I read it, kiddo.” *** Q: What about literature? Do you do reading workshop, as well? A: The samples distributed in class are the only mandatory reading in the writing workshop. There are no books to read. Forcing students to read literature is a sure-fire way to sap their enthusiasm for writing and I don’t want anything to get in the way of their zealous energy to create. Many times throughout the course I will talk about literature with individuals, suggest authors, and even hand out books. However, reading is not a formal element of the course. The second half of In the Middle outlines the basics for a reading workshop. Nowadays, plenty of literature has expanded on the ideas. I’ve tried it, but I never liked it. Of course, in my regular English classes – AP Language or English 9 – there are mandatory novels from the canon to study. *** Q: What if students can’t get writing marked “final” by the deadline? A: If you don’t accomplish enough to get a 65, you do not get a 65. The system is very fair about spelling out what must be achieved by what deadline. It can be an effective learning experience for a student to get an “F” – especially after the first quarter. This grade comes with plenty of counseling along an extended period of time – nobody fails by surprise.8 *** Q: How many teacher-edits can a piece get? A: Infinite. Most pieces need one or two teacher-edits. Some pieces require three or four teacher-edits. A few pieces don’t even get teacher-edit, however. They just get a comment like, “This is too unpolished. Seek out editors and re-submit.” As the course moves along, more first-submissions9 will deserve finals as the class gets the hang of it. Plus, you can tell them: “Try to get finals the first time out of the box. Make it so polished that I only have to read it once.” 8 9 “Crumbling is not an instant’s act,” writes Emily Dickinson. She sure knew what she was talking about. Notice, that didn’t say first drafts. *** Q: There are 50 mini-lessons, but even a half-year course meets for 90 days. What happens on the other days? A: Mostly, they are utilized as full-period, open-workshop periods. After about a month the writing workshop will be operating at full force. Then, start adding open-workshop periods to your week. Also, I suggest taking the class into a computer room several times a year for multi-day stints of open-workshop with technology. Lastly, you can do mini-lessons that come from other sources, add in stricter grammar lessons, and lead them through touchyfeely writing exercises10 that can become inceptions for final pieces. 10 A la Writing Without The Muse, by Beth Baruch Joselow. Now What? Let’s see where you should be now: It’s the middle of Day Two. You’ve gone over the two most important handouts of the course, and everybody is feeling a bit confused about this concept of a workshop. No quizzes? No nightly homework? No books to read? Most kids don’t know if they should jump for joy or drop the class. Don’t panic! Right now you are climbing on top of that wave and it’s about time to start surfing: Hit ‘em with the first mini-lesson (“Stages of Writing/Freewriting”) followed by workshop time. When they come back tomorrow, direct them to set up their chairs, take out their pens and open their notebooks. Then a mini-lesson (“Introduction To Poetry”) followed by workshop time. When they come back tomorrow: Finish the “Introduction to Poetry” mini-lesson (it’s a long one) followed by workshop time. The day after that: mini-lesson (“Bleed on Paper”) followed by workshop time. The day after that: mini-lesson (“The Pebbles Lesson”) followed by workshop time. By the end of the first week, the rhythm of the class will begin to settle in, the students will better understand what’s expected, and the writing will begin to flow. All you have to do is trust the process11: rely on the structures and encourage the students to make their own choices within those structures. During this first week or two, you should find that your time is spent mostly on minilessons and not on the workshop. The course is designed this way because the students need to take in information – a lot of information – before they can fully comprehend what’s “Trust the process” was a motif of a two-week school-administrator workshop I took in July, 2001 called The Leadership Academy at The Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. “Trust the process” is also a great example of sloganeering – a powerful teaching device utilized often in the writing workshop. 11 expected of them. Write ten poems? I don’t even have an idea for one! These kids are dry sponges that need some water – the mini-lessons and the samples they provide are the H2O that will nourish the dehydrated leaves of their creativity. The Roles of the Teacher An important question must be addressed about a student-centered, project-based class like the writing workshop: What does the teacher do? Listed in chronological order, here are some of the hats you will wear on a typical day: 1) Room organizer. Every day, you will likely begin moving the chairs to where you want them and you will tell the kids where to move seats and desks. It’s good to train the students to help, but every day requires some fine tuning. 2) Tone setter. This begins with waiting for complete silence before delivering the mini-lesson. It carries through the mini-lesson when the students see how much you value and enjoy the student-written work that exemplifies the lesson. And it holds steady during the workshop time when you try to keep everybody on task. You must set the tone for an English class where lessons are taught and learned, an art-room where creative muscles are exercised, and a workshop where process-writing is manufactured. 3) Performer of the mini-lesson. Read aloud every word of each mini-lesson to your students and do it in an enthusiastic, passionate way. You might ask students to read the bullet points at the top of a mini-lesson, but don’t have them read aloud the student or professional samples. The fact of the matter is that they butcher them and the poor poetry is murdered instead of celebrated. You must consistently demonstrate effective dramatic readings for your students. There’s plenty of room in the writing workshop for students to learn about oral delivery and practice public performances – especially after the “Dramatic Recitation” mini-lesson. 4) Teacher of note-taking skills. As you read through the mini-lesson and the samples, constantly give explicit directions to teach your students to annotate – in full color. “Highlight the word cinquain on the Robert Frost handout,” you might say as you read it to the class. “And make note that he uses cinquains in the poem ‘The Road not Taken.’” You might also say something like, “Go back over all those student samples we just read and circle in purple the one that impacted you the strongest. Underline a few of the words or phrases that created that impact. When you go into workshop mode, I’m going to come around and ask you which poem you circled and why.” 5) Leader of the transition from mini-lesson to workshop. The most important element: don’t lose any time. Every minute is so precious when you only have 40 a day. A decent transition sounds like this, “And, that’s all I can teach you guys about figurative language. Now open your notebooks, put on your headphones, and make good use out of your workshop time. Utilize those metaphors, but avoid clichés!” Then start sweeping the corners, making sure every student is doing something positive. 6) Option Presenter. Students sometimes need their options spelled out for them. You might draw a mind map on the whiteboard like this one. 7) Workshop facilitator. When students are in their workshop time, walk the room looking for kids off task, kids who need help, and kids who just don’t know what to do. Coach them through the process and always think about this slogan: “Refocus, re-state, and re-teach.” For example, if a student has his head on the desk: “Sorry, Rick, I can’t let you sleep in class. You can go to the nurse if you don’t feel well, though.” “I’m okay, I just don’t have anything to write about.” “The first option then is to freewrite. Just put your pen on the paper, time yourself for ten minutes, and don’t stop writing until time is up.” “Really?” “Yeah, remember I taught that lesson yesterday?” “You did?” “Yeah, let me see your handout from yesterday.” “Um… er…” He fumbles hopelessly with his backpack. “Oy vey! Here, take another one. Freewriting is the best way to see what you’re thinking about. You should try to accumulate four or five freewrites this week, then go over them later and see if there is something you can polish up into a piece meant for a reader.” “Ok, I’ll do it.” “(I say nothing and stand there.)” “Why are you still standing here, Mr. Weinstein?” “Why are you still not freewriting, Rick?” “Ok! Ok! I’m starting!” 8) Collector of submissions. It helps to run an efficient workshop if you can take a look at each piece as it is submitted. Ask three questions – either to the student or to yourself – when you look at a fresh submission: Are early drafts stapled underneath? Did anybody edit it or sign off on it? Is there an addendum? If the piece fails in one or more of these areas, coach the student to get the submission up to par. “Go find someone to read this, edit it, and sign off on it,” you might say. Or, “There’s no addendum. Just hand-write one on the bottom and tell me what the piece is about, what lessons it demonstrates, and what samples you read that inspired it.” 9) Copy editor and sounding board. Show an interest in what the students are working on, listen to them read their work aloud, and make editing and revision comments on the fly. Start the conversation with, “Let me hear you read what you’re working on.” 10) Managing editor and notebook updater. You can use workshop time to update your records on student submissions. The bonus is that you get a quick conference with each student as you record entries on their pages in your notebook (examples in appendix). The image looks like this: The class is engaged in workshop activities, but nobody seems to need your help. Sit at a desk and start recording the “teacher-edits” and “finals” from the folder of submissions from the past one or two days. As you write each one in “the book,” call the writer up and have a conversation about the work. You shouldn’t give back any writing without some face-to-face commentary that supports your written critique. For example, “Great piece! You know I’m always a sucker for a tribute to a parent.” Or, “This piece is developing nicely but a lot of the rhymes are easy clichés. Keep working to make it more advanced; deliver surprises in your rhymes.” Oftentimes, you’ll read a piece and direct the writer to his or her peers: “David, why don’t you show this piece to Ellen. She wrote something just like it last month. Ask her for some editing and get her to sign off on it.” 11) Timekeeper and session-ender. When there is about one minute left in the class announce, “The bell is going to ring in one minute! Put everything away and start helping me put the chairs back in rows.” Since students have three minutes or less to get to their next class, it isn’t fair to let them be surprised when the bell rings. Effective Teaching Techniques in the Workshop Every great craftsman needs to understand the basic tools of the trade. Here are some fundamental teaching techniques to make your writing workshop more effective. 1) Never talk when they talk. This must start on Day One. You don’t have to be mean or angry – you just have to wait. You have to train your students and teach them to listen. “Eyes on me, mouth closed,” is a really effective slogan. “Put down all technology, too! Let me see your eyes up here. Thank you.” Then give a stewardess smile and proceed. 2) Give explicit directions. Students don’t know what to do unless you tell them what to do. This is true for everything from taking out a pen to writing down notes. Remember to give them time to comply with your instructions, coach them through the process, and acknowledge students who don’t follow along. Be careful to avoid public embarrassment – a short personal conversation in a quiet tone is a more effective teaching technique than raising your voice, making a student feel small, or public humiliation. 3) Always teach annotation. Kids have to be taught how to be good students before they can be taught the subject matter. Look for ways to teach them scholarly skills like studying and note-taking. 4) Practice the Whip.12 The whip-around-the-room means that every student gets to say something. It can be applied to just about any lesson and is effectively paired with prewriting. Here’s an example of how it works: 12 Credit for the whip goes to Dr. Jack Conklin from The Leadership Academy at MCLA. “Today’s lesson begins with making a list of places you remember from childhood. Take the next four minutes and make a list of places that were special to you – could be as big as Tokyo and as small as the sandbox at Lakeville Elementary. Then, in four minutes, we’ll do a whip around the room and see what we came up with.” (Four minutes later…) “Ok, Carmen you start us off. Tell us one place off your list,” you say. “The spare bedroom in my grandmother’s house in Flushing,” Carmen says. Point to the writer next to her. “Jen?” “San Francisco,” Jen says. Point to the next kid. “Pat?” “My old house – the basement there,” Pat says. And so on until every kid has had a say. The whip is a powerful tool of sharing ideas and building a community in your classroom. I try to do at least one whip-around-the-room every two weeks. It’s a timeconsuming activity but it is vital to an effective workshop for a few reasons: a) Students work on public speaking. In fact, during the whip you can coach them to be better public speakers. I designed the mini-lesson entitled “The Fundamentals of Dramatic Recitation” because of the weaknesses exposed during the whips. b) Students work on listening. You have to teach them how to listen: eyes on the speaker, mouth closed, technology down, and nods of understanding. c) Student voices are recognized and valued. Every pupil speaks during the whip and each one is recognized for contributing to class. d) It breaks up the monotony. How often during a school-day does a student take part in a whip-like activity? It’s fun and invigorates the workshop. e) Ideas are shared. The whip acts like a Facebook wall and everybody creates a post. Then, students can borrow ideas or take inspiration from classmates. “Oh yeah, I loved San Francisco when I spent a week there when I was seven!” is the type of comment you might here during a whip. Tell your students to, “Write down any new ideas you get during the whip.” f) Class-building. When everyone has to speak, everyone sees who shares some common ground. It breaks down barriers, warms up the climate, and sparks friendships and collaborations. “Hey, Jen, why don’t you and Sally get together and see if you can do something together on San Francisco,” you might say later in the workshop. T he whip can also substitute for the minilesson and help you take the temperature of the class, find out what lessons and samples have been effective, and give learners a chance to work on their public speaking skills. Don’t forget to give them time to make a choice and rehearse. Create a mind map of options for a great whip. 5) Utilize think-pair-share.13 When you ask kids to think about something or to brainstorm an idea, there needs to be a follow-up activity to process the information. Think-pairshare can work well to achieve this goal. It’s very simple to execute and can be applied to nearly any lesson. It looks like this: “Yesterday we learned two different ways to use a semicolon.14 Review your notes if you have to, but I want everyone to write two example sentences – demonstrate the two different ways to use a semicolon. All sentences have to relate to writing. You have two minutes to accomplish this. When you are done, put your pen down and that will be the signal that you’ve finished the two sentences.” During the two minutes, circulate around the room and coach the students. “OK, now that everyone’s pen is down and we’re all done. I want you to pair up with the person sitting next to you. Shake hands with each other. Say hello. Give each other a compliment…Now, show each other your two sentences. Let each other know if they were done correctly and if they demonstrate the two lessons we learned yesterday. Help each other learn the lessons. Call me over if you need my assistance.” You know what happens next? Interactive learning! They talk about the sentences, the lessons, and the semicolons. They teach and learn together – and you coach the process. Look for students who didn’t pair up and find a way to get them involved in the process. Think-pair-share is designed by Spencer Kagan, and is one of hundreds of “cooperative learning” techniques outlined in his books and taught in his workshops. During my first year in the classroom, I took a course on Kagan cooperative learning class en route to my M.A.T. from SUNY-Stony Brook. For a few years afterward, I tried to latch onto cooperative learning as my central philosophy of education. I eventually ditched it in favor of writing workshop – you can only have one dominant paradigm, right? However, techniques like think-pair-share are awesome educational strategies and they should be in your toolbox. 13 Notice the transition technique modeled here: Use a good writing exercise to bridge the gap between yesterday’s class and today’s. 14 6) Set time limits.15 Whenever you give students explicit directions, it should be followed by a time constraint. After all, what’s a goal without a deadline? Giving them time constraints gets them on task and gives them a sense of urgency. “Fifteen seconds left to list places you remember well as a child!” you should call out. The students will scramble to get their last thoughts down on paper. You could use a real timer or throw one up on-screen, but I prefer something a bit less formal. It works just as well in larger chunks of time. “You have 20 minutes remaining for workshop time – use those minutes effectively!” you might call out to the class. It’s even effective for long-term reminders: “There are six days left to submit new writing for this quarter. Stop waiting and start turning in writing!” 7) Say, “Write it!” It’s not the most complex technique, but it is darn effective. Students are going to love your workshop for its freedom, its fun, and its social interaction. It’s only natural that they will talk about anything and everything with each other. Combat this by constantly directing them to, “Write it!” Two boys are talking about last night’s Yankee game: “Hey, why don’t you two guys work on a piece about the Yankees?” Two girls are talking about going to the mall after school: “How about a piece about shopping?” When you overhear conversation that seems to be distracting your students, walk over and re-direct their dialogue into their writing. Credit, again, goes to Spencer Kagan. I’m sure the guy didn’t invent the time limit, but he emphasizes it enough that he deserves this footnote. 15 Take Advantage of Technology You have already read how to encourage your students to utilize technology in the writing workshop, but what about the teacher? I’m not great with technology and I’m way behind some of my colleagues – I don’t keep a website or do my grades on the school’s “Gradebook” program. I still use an actual notebook to track my students’ submissions! Sometimes technology is a frustrating time-killer that hinders the educational process. For example, when I try to use the Smartboard, suddenly my attention is on the technology and not on my students. And, suddenly their attention is on me instead of on their writing. It makes me uncomfortable. I know this isn’t true for everybody; I know plenty of great teachers making effective use of the Smartboard and other technology, but it’s just not a good fit for me. However, there are many ways that I integrate technology into the writing workshop. Here’s how you can too: a) Show music videos and dissect lyrics. The computer has gone big screen thanks to the Proxima Projector. It is a powerful teaching device in any classroom for a thousand different reasons. Try it for music videos at Youtube. The dual assault on the ears and the eyes is irresistible. Playing the video of a popular song is a nofail hook to motivate the lesson.16 Give it a minute to soak in. Let them move to the song.17 Then open another tab on your browser and do a Google search for the Stick with contemporary hits, trust me. Don’t try to “expand their horizons” by forcing them to listen to your crappy music. It will only distract from the lesson. 16 17 You’re my hero if they get up and dance – kinesthetic learning takes high-level teaching. lyrics18. From here, lead a class discussion of the writing techniques on display. For example: 1. The “Listing Techniques” mini-lesson includes Billy Joel’s video for “We Didn’t Start the Fire” and an analysis of his lists: the details he chose, the allusions he made, the organization of the material, and the development of the rhymes. 2. The “Epistolary Poetry” mini-lesson ends by showing Eminem’s “Stan” and discussing the letter-writing technique, interior rhymes, imagery, and concrete details. Studying these professionals is an eye-opening experience for students who never thought of their favorite singers – today’s highest-paid poets19 – as writers. The “Poetic Analysis” mini-lesson inspires many students to break down the writing techniques behind their favorite songs. 3. Search for information on-line. We all know how Google works these days and there’s no reason to ignore it in the classroom. In fact, you should try to incorporate it – and other websites – into your lessons. It is vital that students be taught how to properly search for information on-line, and who better to demonstrate the safest methods and best practices than their teacher? Anytime you need to “show don’t tell,” go to the Internet and take the students with you. 18 See, this right there can be a great lesson: How to find information on the Internet. Wikipedia lists Jay-Z’s net worth at $150 million. Diddy is worth twice as much. Are these guys the highest-paid poets in history, or what? 19 The Internet In My Room I have shown the Wikipedia entries on everything from the McCarthy Hearings blackball list (shockingly long) to the Battle of The Somme (shockingly brutal). We checked out the entries on Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Cummings, and more. We also looked at Kanye West’s website when he posted an essay called “Creativity” and skimmed a Times article about Emily Dickinson’s gardening skills. (She was better known for horticulture than poetry during her lifetime – who knew!?) Whether it’s a part of the lesson plan or a spontaneous impulse, utilize the Internet to modernize your teaching practice. 4. Use Microsoft Word on the projector. Demonstrate your writing for the class. Now that the computer is on the big screen, this is much easier and much more fun. You might create your own example sentences with semicolons or create a list of places you knew well as a child. Caution: You have exactly two minutes to write at the computer – then your students will begin to lose focus. At the three-minute mark you will hear talking and minor wrestling. At four minutes students sneak out of the room or play poker. After five minutes a bottle- breaking, rock-throwing coup d’état is fully underway. 5. Take the class to a computer lab. Once a semester, get your classes into a new location: the writing lab. It will benefit students mightily to have a three- or four-day stint of high-tech workshop time. During these sessions you will feel like the managing editor of a magazine: work is coming in and going out, you’re editing onscreen all over the place, students are collaborating, and writing is being created at break-neck speed. You don’t want to hold the course in a writing lab all the time because the primitive pen-marker-notebook trio is essential to the writing workshop. My dream classroom includes five to ten new computers, high-speed internet, scanners, and color laser printers. It would double the student options for workshop time and more fully integrate technology and self-publication into the writing workshop. (As long as it’s a dream, throw in a technology specialist interested in team-teaching and carpooling from Manhattan.) Critiquing Student Submissions I admit it unabashedly: I love the red pen. I am particularly fond of Uni-ball fine point red pens. Spare me your argument against the crimson critique. I have studied the essays decrying the practice and a quick Google search reveals plenty of agita on the topic. Even my mom – a teacher-turned-principal – is "The Pen." against the red pen! Well, I don’t care. I’ve tried purple and green, blue and black and ya’ know what? I don’t like ‘em. I love the way my Uni-ball fine point feels in my hands. I know; it’s so ironic, right? My students are known throughout the school for taking colorful notes with magic markers, and I use the traditional red pen. Sorry! I love its fireand-brimstone authority. I love how it stands out on the page. I love it so much I’m going to take it out for a nice dinner and then try to get it pregnant.20 Whether you use red ink or not, keep the following tips in mind when you sit down to evaluate student submissions: a) Say something positive. You know this one: You can catch more flies with honey than vinegar.21 The power of positive reinforcement cannot be underestimated in your writing workshop. Writing is so personal and so sensitive that the commentary – especially in bright red ink – can be damaging to the student’s ego and sap the motivation to learn. It is critical that the writer knows something about the piece is moving in the right direction. 20 Joke stolen from Tracy Morgan’s character on 30 Rock. 21 Oh man, what a cliché! Where’s my red pen? b) Be brutally honest. While it is important to be positive, it is equally important to give the student real feedback about weaknesses in the piece. However, you still need to tread lightly and remember that certain delicate situations require a conversation rather than a written critique.22 c) Comment about the writing, not the writer. Make sure you critique the piece and not the pupil. This helps avoid misinterpreted comments, hurt feelings, and other problems. You might think effusive praise like “You are one heck of a writer!” can only be positive. But the truth is that it can only lead to problems. Suppose the next piece the student submits isn’t up to par? You built up expectations with that last comment and the new criticism could become difficult for the youngster (or the parents) to absorb.23 Look at these critiques and determine which are appropriate: 1. “This piece is too vague in key areas.” 2. “You are too vague.” 3. “This piece is terrific!” 4. “You are terrific!” 5. “This needs more imagery of your sisters.” 6. “You don’t use enough imagery.” CYA, dude. Remember that parents and administrators can read your comments. Be truthful, but don’t go overboard and don’t put something in writing that you might regret. Sometimes the only thing I write on a submission is this: “Let’s talk about this one.” 22 Between Parent and Child by Dr. Haim G. Ginott emphasizes the importance of controlling a child’s expectations through this technique and similar models. 23 d) Use the slogans. A benefit of sloganeering is that you can design a shorthand method of communicating with your students. Almost every mini-lesson has a one- or twoword catchphrase that’s memorable and reminds the writers what was taught in class. You only need to write “Add pebbles!” for the student to know the piece is lacking in the gutsy details that will elevate the writing. e) Look for lessons to teach. When you examine the mini-lessons, you won’t find many about basic grammar and punctuation. However, English teachers have to teach some proper lessons, right? The trick is to discover what lesson needs to be taught to which student through his or her writing. Every student gets an IEP! You only have to read one paragraph to see that a student needs to learn about commas, apostrophes, or agreements. When you start to see trends emerging from across the class – Does anybody in this room understand the difference between “good” and “well”? – You should design a mini-lesson that fills in the gaps of their knowledge. (Then put it on the test!) f) Ask yourself: Can it be any better? This is the central question pertaining to your roles as teacher, editor, coach, and motivator. How can you push this student, this piece, this idea to be even stronger and more effective? How can it be improved? If you put a “T-E” on a submission, you have to justify it. Only mark a piece as “Final” when the answer to the question is this: It can’t be any better.24 OK, that’s a bit of an exaggeration. I hand back “finals” every day that still need some minor corrections – maybe an apostrophe should be added or a spelling error fixed. “Just make those last corrections for your portfolio,” I will say to the student. “But, I don’t need to see it again. I think it’s a great piece!” 24 Common Critiques on Student Submissions No addendum? No drafts? Revise and resubmit. Impressive evidence of the drafting process. This poem is dying for a rhyme scheme. Killer rhymes. Take more risks! Bleed more! I feel your pain. Needs pebbles. Great original details! Weak writing. Powerful poetry, kiddo. A bit confusing. Nicely expressed. Let’s talk about apostrophes. Superb semicolon. Try long dashes here. Good example of our lesson! Show don’t tell. Excellent imagery. Keep writing! It ended too quickly. Powerful last words. Awkward word choice. Smooth transition. A memoir needs a climax and conflict – try again. This piece was worth reading. Let’s discuss this one together. Right on! Superb Stuff, Brandon.25 Review the sonnet lesson. Resubmit. Superb sonnet. Add color to this one for your portfolio. This is an eye-catcher. Too cliché. Original idea. Tone down the language a bit. Wonderful word choice. Sharpen the contrast developing here. Effective contrast. Study handout on dialogue style. Can I get a copy to use as a sample? Of course, one comment stands above all others: “Final.” I don’t only write one of these comments on a paper, but you get the gist of it. I always try to say something positive, be economical in my comments, and teach what I can where I can. 25 Obviously, only use this comment for Brandon. But feel free to change the name as necessary. Try writing a student’s name on the paper for emphasis: “Schwartz, this one really packs a punch. Nice pebbles.” In addition to my comments, I’ve developed a system of check-marks to let the writers know when they have written particularly effective words, phrase, or sentences. I just drop the check-mark(s) into their writing as it inspires me. A simple check-mark next to a well-crafted sentence can have a deep impact on a young writer. The system basically works like this: = This is mildly clever. = This is a nice sentence, dude! = Epic. Just epic.26 Once your students start taking risks and writing from their hearts, you will be shocked at how they value your feedback. Most pupils will make all your corrections and strive to satisfy each of your demands as the piece goes through the writing process. You want more pebbles? Fine! More pebbles! A strong bond begins to develop as the teacher and student form a writereditor relationship. 26 Credit to Rachel Dicker, former student and NCTE winner. Incorporating Writing Workshop into a Traditional English Class The philosophies and concepts covered in this book can easily be integrated into any English class. What’s more, when you see the writing your students do in the workshop, you’ll realize that it is vital to include a “Creative Component” into every course you teach. I fit almost my entire Creative Writing course into the full-year, traditional classes I teach – whether it’s Language Arts for Freshmen or English 11AP. I do this by compartmentalizing: For four weeks we study a novel. For two weeks we do writing workshop. For a few days we work on reading comprehension passages. For two weeks we do writing workshop. Or, you could break it down into smaller bites: Mondays and Tuesdays are literature days. Wednesdays and Thursdays are writing workshop. Fridays are for grammar lessons. You have to experiment to see how you feel most comfortable. The difficulty is that once the students go through some writing workshop periods, they won’t want to do anything else. Combat this by utilizing all the ideas and philosophies discussed in this book – the seating arrangement, the teaching techniques, the technology, etc. – no matter what subject matter you’re covering. If you always try to be student-centered and project-based, the writing workshop will be smoothly integrated into the class. Once your students understand the basics of workshopping, you can utilize its structures to cover other areas of the curriculum. For example: Add a statement like this to your creative requirements: “Read a nonfiction book and submit a one-page style analysis on it.” Now, you’ve established an outside reading goal and an accompanying writing task as part of the creative component. Develop lesson-plans that begin with these types of statements: “Let’s use the writing workshop over the next three days to work on the research papers due next month. You can research, edit, collaborate, or do anything else necessary to advance your paper.” Liven up a dull lesson by stating a goal and giving them workshop time to accomplish it: “You each have a copy of the grammar book in front of you. Teach yourself the difference between a linking verb and a helping verb during the next 20 minutes of workshop time. Tomorrow begins with a quiz on these very different verbs.” On the next page is an example of the first-quarter “Goals & Deadlines” for my AP Language & Rhetoric course. This is a full-year class, compared to the half-year Creative Writing.27 The big difference is the amount of class-time spent in writing workshop – it’s less in the traditional class even if there are twice as many days. Incorporating a “Creative Component” into your curriculum demands the students do a lot of work outside the class – it is the de facto homework.28 27 Of course, you also must prepare them for standardized tests, study Shakespeare, get through a research paper, etc. etc. You can accomplish all that and STILL incorporate writing workshop. What’s the sacrifice? Students read fewer books from the cannon. It’s worth it – besides, all the other English teachers will pick up your slack by mitigating creative writing and force-feeding literature. One year with a creative dynamo like you helps balance out the four-year education. 28 It gets challenging when you add reading assignments to complete and exams to study for. The creative demands of the class are always in the students’ minds. (See why you have to limit pissant daily homework assignments? They distract more than they educate; sap energy rather than inspire enthusiasm.) This class has to spend the first two weeks analyzing the summer reading assignment, Richard Wright’s Black Boy. During this time, they also have to learn how to write a styleanalysis essay.29 They won’t get the “Goals & Deadlines” handout until we get into that block of writing workshop days. The next two weeks after that will be devoted to getting the writing workshop off the ground. Then, we’ll loop back around to two weeks of literature, essay skills, and the like. How the Creative Component Impacts the Grade Explain that the writing goals are mandatory requirements for the grade on the left of the chart. There is no separate grade for the creative writing done by students in traditional, full-year English classes. It’s really quite simple: If students want to get an “A” on their report cards, they need an “A” average on tests on quizzes AND they need to meet the “final” requirements for a 90+. Less than the goal = less than the grade. This concept is reinforced on the bottom of the “Goals & Deadlines” handout, but it requires patient explanation. The style-analysis essay is part of the AP exam. If you want to see exactly how I teach the AP course … buy my next book! 29 AP Language & Composition Fall, 2011 Goals & Deadlines – 1st Quarter Important First-Quarter Dates Wed. 9/29 Fri. 10/8 Wed. 11/3 Wed. 11/10 Mon. 11/15 Creative writing submissions accepted Interim reports are due Last day to submit new creative writing Final deadline for all rewrites Last official day of marking period “Final” Requirements for First-Quarter Grades 90+ 3 poems of any style 2 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 3 mind maps or other artistic piece One outside reading of a nonfiction book w/one-page style analysis. 80+ 2 poems of any style 2 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 2 mind maps or other artistic piece One outside reading of a nonfiction book w/one-page style analysis. 70+ 1 poem of any style 1 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 1 mind maps or other artistic piece One outside reading of a nonfiction book w/one-page style analysis. 65 1 poem of any style 1 pages of memoir or other prose (typed, double-spaced, 12-point) 1 mind maps or other artistic piece One outside reading of a nonfiction book w/one-page style analysis. Your Quarterly Grade: If you want an “A” in the class, it is NOT enough to have an “A” average on tests and quizzes. You must also satisfy the creative requirements for that score. For example, if you have an average of 95 on all tests and quizzes but, you fail to satisfy the creative requirements for a 90+, the highest grade you can get for the quarter is an 89. If you have a 99 average but don’t satisfy the creative requirements for a 65, you will NOT even get a 65 for the marking period. Chapter Two Summary 1) The “Goals & Deadlines” handout is a crucial part of establishing the workshop. The students know exactly what must be accomplished by exactly what date. It also puts you in position to get behind your students and help them achieve the goals by the deadlines. 2) “Less than the goal is less than the grade.” 3) Students may go off the rubric and produce almost any type of writing or art they desire. Your job is to discover who has this interest and then encourage them to follow their instincts. Establish new goals with students who have unique ideas. 4) After you get through the two opening handouts (Daily Habits and Goals & Deadlines) it’s time to start surfing. Almost every day for the rest of the year will follow a predictable rhythm: mini-lesson then workshop time. 5) The workshop teacher has to fill many roles. You have to flexible, agile, and possess the withitness to know which situations require what roles.30 6) Create mind maps of the options for workshop sessions. This gives the students concrete ideas for how to spend the time productively. 7) Utilize the student-centered teaching strategies. Explicit directions, whips, annotating, think-pair-share and the other techniques make the workshop work. 8) Incorporate technology into your classroom every way you can. Whether it’s showing music videos, looking up information on-line, or demonstrating writing, teachers can simply and effectively take advantage of these powerful tools. 9) Your critique of their writing is pivotal to a successful workshop. You alone determine if a piece is teacher-edit or final. You have to be positive but honest. Teach lessons where you see they’re needed, bolster their confidence, and nurture the editor-writer relationship. 10) It’s easy to integrate the writing workshop into any traditional, full-year English course. Modifications need to be made, but the results are the same: students leave your course with a great experience and an impressive portfolio. “Withitness” is described as the preeminent character trait of great teachers in Malcolm Gadwell’s New Yorker article: “Most Likely to Succeed: How Do We Hire When We Can’t Tell Who’s Right For The Job?” Dec. 15, 2008. 30