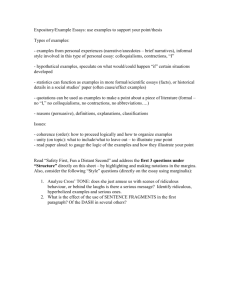

How well does Marginalia incorporate research-based

advertisement

The Second Generation of Online Discussion Forums: Going Beyond Marginalia to Ice-Cream author author Abstract: This paper describes our design efforts to create a pedagogically viable web-based discussion forum software. Popular web-based systems do not thoughtfully make use of pedagogically supportive features. Marginalia adds a set of pedaggical features to Moodle. We have analyzed reactions and usage in several universitylevel courses in a variety of disciplines and institutions. Based on these evaluations and drawing on developmental theory and researchbased principles regarding software design, we are going beyond Marginalia to ‘IceCream.’ It will have different feature sets available flexibly for elementary, high school and adult. Features will support self-regulatory processes, as well as target writing and reading online skills. Literature Review Text based discussion forums have been around for some time now. Over the past two decades, many researchers have written about the pedagogical potential of forums for reflection, critical thinking, and collaborative learning. But a number of recent studies have found that there is a lack of deep engagement, and that students do not view forums as a space for critical discourse (Fahy, 2005; Friesen, 2009; Gao & Wong, 2008; Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000; Lee & Jeong, 2009; Osman & Duffy, 2009; Rourke & Kanuka, 2007; Shea & Bidjerano, 2009). Feenberg (Feenberg1989; Feenberg & Xin; 2003; Xin & Feenberg, 2007) argued that leadership or moderating, one form of student-teacher interaction and student-student interaction, is one of the key factors determining the quality of learning in online forums. They proposed a set of moderating functions that are fulfilled primarily by the teacher but that can be more or less distributed among the members of the class. These functions bear both social and intellectual content. The effective performance of these functions initiates, sustains, and advances dialogue. Unfortunately, popular software packages do not necessarily facilitate moderating functions or other ways to create a healthy online learning environment. Widely-used forums, such as those in popular course management systems like WebCT, Blackboard, and Moodle, are little different from those used in the early days of web-based course management systems. Indeed, apart from cosmetic changes, most current forum interfaces are quite similar to the original newsgroup programs from which they descend. The design has been relatively generic in contrast to the design of decision support tools where design decisions vary widely based on the context: for example, the nature of the tasks to be undertaken, and the intentions or aims of participants (Sloffer, Dueber & Duffy, 1999). Some have argued that web forums support divergent thinking, and hence convergent thinking needs to be supported by something, be that the moderator, the nature of the assignments, or the design of the conference system itself (Harasim, 1993; Hara, Bonk & Angeli, 2000). The given affordances of the system (Gibson, 1977) may not provide enough structure to support certain types of higher-level thinking. In the early days of online discussion forums, it was already recognized that discussion forums needed some types of scaffolds to facilitate pedagogical interactions. Their nature may better support divergent thinking, and hence convergent thinking needs to be supported by something, be that the moderator, the nature of the assignments, or the design of the conference system itself (Harasim, 1993; Hara, Bonk & Angeli, 2000). The given affordances of the system (Gibson, 1977) may not provide enough structure to support certain types of higher-level thinking. Unfortunately, most forays into creating more pedagogically appropriate software with features built-in to support co-construction of knowledge have been limited to softwares such as Knowledge Forum (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1993), and TextWeaver (Xin & Feenberg, 2002), and thus far they have not succeeded in entering the mainstream. Computer conferencing has become part of web-based course-management softwares which are often used by instructors as one-way communication tools to post course information. Theses software packages do not necessarily facilitate moderating functions or other ways to create a healthy online learning environment. Widely-used forums, such as those in popular course management systems like WebCT, Blackboard, and Moodle, are little different from those used in the early days of web-based course management systems. Indeed, apart from cosmetic changes, most current forum interfaces are quite similar to the original newsgroup programs from which they descend. The design has been relatively generic in contrast to the design of decision support tools where design decisions vary widely based on the context: for example, the nature of the tasks to be undertaken, and the intentions or aims of participants (Sloffer, Dueber & Duffy, 1999). One of the authors developed Textweaver in an attempt to address the pedagogical limitations of existing forums, but faced with the problem of adoption turned his efforts toward building Marginalia [References removed for blind coding.] The other authors (2010, 2011) developed and studied a labelling feature for use in Vbulletin, amongst others, and then turned our attentions toward Marginalia as well. We explored the impacts of labelling on student discourse and found that labelling predicted better quality dialogue even when students’ general text comprehension and task-specific motivation were accounted for. Marginalia is an open source extension to Moodle, a web-based course management system. Marginalia adds annotation (a student-content and student-student activity), tagging (a student-student activity), and several other features potentially useful for enhancing online discussion. A number of studies have found annotation helpful for online learning (Bateman, Brooks, Mccalla & Brusilovsky, 2007; Carusi, 2003; Farzan & Brusilovsky, 2008; Huang, Huang & Hsieh, 2008; Kaplan & Chisik, 2005; Lee & Calandra, 2004; Nokelainen, Miettinen, Kurhila, Floréen & Tirri, 2005). The introduction of keywords and tags or labels for messages mirrors the rise of Web 2.0 technologies where users tag videos and other artifacts to facilitate retrieval of relevant items such as in YouTube or Diig. Our focus on scaffolding features or collaborative scripts reflects concern amongst practitioners and researchers that the unstructured forum discussions do not support an effective learning environment. In Bernard et al. (2009) they quantitatively provided evidence that interaction in DE has positive benefits, including student-student, student-content, and student-instructor interaction. Each type of interaction had a significantly positive average effect size ranging from +0.32 for student-instructor interaction to +0.49 for student-student interaction. But could we do better? In Abrami et al (in press) we argued that this meta-analysis was really about the impact of the first generation of interactive distance education, where online learning instructional design and technology treatments allowed or enabled some degree of interaction to occur. In first generation interactive distance education learners were able to interact but may not have done so optimally. These interactions may have been limited by how the courses used in the research were designed and delivered and limited by how technology mediated learning and instruction. Consequently, the next generation of interactive distance education (IDE2), or purposeful, interactive distance education, should be better designed to facilitate interactions that are more targeted, intentional and engaging. Not only will we need knowledge tools and instructional designs that do this effectively, but we will also need research that validates both the underlying processes (e.g., using implementation checks and measures of treatment integrity) as well as the outcomes of second generation interactive distance education (e.g., especially measures of student learning). Marginalia Design Features Marginalia was originally developed drawing on TextWeaver. Key features to support annotation (highlighting and commenting), tagging, and quoting were included. While we were pilot-testing it in a variety of university-level courses we made important changes to the design as are explained below. The key features currently are: Creating highlights and annotations. The software’s core feature is annotation: the capability to highlight passages of text in forum posts and write short notes in the margin next to them, just as the reader of a book might underline passages and scribble notes in the margin. An annotation can be edited after creation. Annotations allow users to select out and comment on what they find to be the most interesting or important ideas in a discussion for future reference. Being able to see the marginal notes alongside the posts creates the visual connection between the reader’s reactions and the context, a link that is typically missing in standard forums. Public vs. private annotations. When a user creates an annotation, s/he may choose to make it private or public. If it is private, only s/he can view it. If it is public, it is available for others to read. The designers decided that by default, all annotations should be public. This design choice was made deliberately in a hope that people would share. Indeed, they did, and to the designers’ surprise, in some contexts the students have used the margin as a second channel of communication [REFERENCES omitted for blind coding]. Summary of annotations. To facilitate retrieval and make use of archived materials, annotations are also collected together on a separate summary page, where they are displayed alongside the highlighted excerpt to which they refer. The summary can be searched and filtered. For example, a user might choose to search the summary for annotations containing a particular phrase, or view only annotations by a particular user. Quoting. A special quoting feature was implemented to make it easier to quote other discussion posts and encourage attribution. To use this feature, a participant highlights a passage of text that he wishes to quote and then simply click on the quote button. The highlighted text is automatically pasted into the reply window with a hyperlink to its original post. This can be done repeatedly to include multiple quotes in a single reply. A quote button beside each margin note allows them to be quoted in the same fashion. This is particularly useful for writing weaving comments.. Tagging/Keywords. Marginalia makes it easy to establish and use a fixed vocabulary for marginal notes. Marginalia detects when the same note is used more than once and offers to autocomplete subsequent uses. The note is then called a “tag.” Standard schemas like this can be pedagogically valuable. For example, a teacher and/or students can create a set of pre-defined tags for students to apply when reading each other's posts; this can be used to drive various types of further engagement, such as main points to be summarized, new areas of discussion, questions to be followed up, and so on. Alternatively, tagging can be used to simplify future retrieval of annotations about a particular topic. [INSERT SCREENSHOTS; ANNOTATION IN USE] Evaluation of Marginalia Originally Marginalia was intended to make it easier to read, recall, and write forum posts. Marginalia was expected to be especially useful for gathering the ideas and references for writing effective weaving comments. Through early development, various unanticipated uses of the tool emerged, and we made choices drawing on our understanding of the principles discussed in this paper. The intended use—reviewing the text to support weaving and other moderator functions— is only one of many ways the designers saw users use the feature. The nature of the task was related to how students used the feature. In a recent study eight key benefits from the students’ perspective were documented: Gaining Insight into others’ thoughts, Instructor feedback (studentteacher), Developing Critical understanding (student-content), Reviewing text (student-content), Highlighting (student-content, student-student and student-teacher), Group Processes (studentstudent), Relevance, Insight into others’ perceptions of one’s writing, Dialogue in Margins [REFERENCES removed for blind coding]. Notice that some of these benefits support studentcontent interaction including developing critical understanding and reviewing text; others support student-student interaction including group processes and dialogue in margins; still others support student-teacher interaction. Conceived as a tool to help students use the potential to review and re-read online dialogue for their own learning purposes, supporting student-content interaction, users have demonstrated a range of other potentials which support student-student and student-teacher interaction. The annotations or marginal notes and the keyword features were expected to be primarily a private tool which students used to highlight and comment on the most relevant parts of the dialogue. When the designers chose to make the default of the annotations public, a range of possible uses of the tool emerged including students using the side-column where the marginal notes appear as another form of communication between themselves and sometimes the instructor. In some contexts, students were discussing the group process on the side, separating out the organizational messages from the actual content messages, and in other cases they were making more casual comments than they would in the forum posts, providing more immediate reactions to the messages. In some cases, students even began to respond to each other’s annotations in the margins. These uses of the feature are interesting and may support group processes; on the other hand, they may cause cognitive overload problems as learners wonder which dialogue is the main dialogue. Hence, we decided to design a button to lead them back to the main discussion space when they respond directly to an annotation, so that they would not actually carry out a second dialogue in the margins, and to limit the length of their annotations to 250 characters. Our thinking at the time was that marginal notes are not intended to substitute for forum posts; rather they are snapshots of a reader’s thoughts. Still, these decisions remained controversial and indeed, students largely ignored the return to dialogue button and circumvented the design in order to respond to others’ annotations in the margins. Many students saw the annotation tool largely as a way to interact with others about the content, not as a review tool for themselves. A concern raised in the testing of Marginalia was student up-take. Although some students were active users of the annotation feature, most were not except when assigned a specific task related to its use. For example the first author had students use the feature to highlight parts of messages in order to select out highlights to place into their electronic portfolios; in this case all students used it, and in the original conceived way – as a review tool. But when left to their own devices, most learners did not tend to use the feature actively. Previous research suggests that learners do not always make the best choices regarding the use of learning strategies and that certain individual characteristics predict voluntary use of learning strategies. Students may benefit from strategies, but will not necessarily use them, and the ones who may benefit most may be less likely to use them. Abrami et al (in press) considered several reasons why learners do not better utilize some knowledge tools. The first is based on the principle of least effort. Even the best strategic learners need to balance efficiency concerns with effectiveness concerns, as well as balance proximal goals with distal ones. Second, strategic learners often have to find the balance between intrinsic interests and extrinsic requirements. Frankly, the postsecondary learning environment imposes course requirements that may not make effortful strategies uniformly appropriate. Third, Weiner (1980) showed how causal attributions for task outcomes varied among learners, and that defensive attributions for failure (e.g., I failed because the exam was too hard or my teacher did not help) help protect a learner’s sense of self-efficacy. Increased personal responsibility for learning is not always beneficial to a learner’s achievement strivings. Fourth, productive learners believe that their efforts at learning lead to successful learning outcomes, but some learners believe that their efforts bear little, if any, relationship to learning outcomes, called learned helplessness (Seligman, 1975). Fifth, in order to encourage active collaboration among learners, it is often necessary at the outset to impose external structures including individual accountability and positive interdependence to insure that each learner knows that s/he is responsible for his/her own learning within a group and that s/he is also responsible for the learning of others (Abrami et al., 1995). Knowledge tools appear to work best when there is a meaningful complex task (i.e. Bransford, Sherwood, Vye & Rieser, 1986), when the task demands multiple expertise not just multiple efforts, when students value the task, when students know what their contribution is, and when there are tools that help support the learner in effectively completing the task. Strategies such as annotation and tagging are ways to facilitate students’ engagement online. When students use Marginalia, opportunities for interaction exist but this does not mean that students availed themselves of them, or if they did interact, that they did so effectively. Consequently, the next generation of Marginalia should be better designed to facilitate more purposeful interaction. Guided, focused and purposeful interaction goes beyond whether opportunities for interaction exist to consider especially why and how interaction occurs. When students consider why they engage in learning activities they are reflecting on their motivation (from the latin word “movere” meaning to move) for learning including the energy of activity and the direction of that energy towards a goal. When students consider how they engage in learning they consider, or are provided with, the strategies and techniques for knowledge acquisition. How well does Marginalia incorporate research-based principles with implications for the design of the enext generation of distance education? In embarking on moving ‘beyond marginalia’, we have conducted an analysis of the results during the pilot-testing and considered how to effectively move to the next phase. Previously we explored research-based principles regarding self-regulated learning, multi-media, motivation, and collaborative and cooperative learning with implications for design of the next generation of interactive distance education [REFERENCE REMOVED FOR BLIND CODING] (Table 1). Here we analyze how well Marginalia incorporates these principles. Table 1. Principles for the design of the next generation of interactive distance education [REFerence removed for blind coding] Self-regulated learning principles: 1. The forethought phase includes task analysis (goal setting and strategic planning) and self-motivation beliefs (self-efficacy, outcome expectations, intrinsic interest/value and goal orientation). 2. The performance phase includes self-control (self-instruction, imagery, attention focusing and task strategies) and self-observation (self-recording and self-experimentation). 3. The self-reflection phase includes self-judgment (self-evaluation and casual attribution) and self-reaction (self-satisfaction/affect and adaptive-defensive responses). Multimedia learning principles: 1. Reduce extraneous processing and the waste of cognitive capacity. 2. Manage essential processing and reducing complexity. 3. Foster generative processing and encourage the use of cognitive capacity. Motivational design principles 1. Adaptive self-efficacy and competence beliefs motivate students. 2. Adaptive attributions and control beliefs motivate students. 3. Higher levels of interest and intrinsic motivation stimulate students’ learning. 4. Higher levels of value motivate students. 5. Goals motivate and direct students. 6. Participating in a context where knowledge is valued and used motivates students. Collaborative and cooperative learning principles 1. Positive interdependence exists when one student’s success positively influences the chances of other students’ successes. 2. Individual accountability involves two components: a) each student is responsible for his or her own learning and b) each student is responsible for helping the other group members learn. 3. Promotive interactions occur as individuals encourage and facilitate each other’s efforts to accomplish the group’s goals. 4. Effective collaboration includes giving and receiving elaborated explanations with a focus on encouraging understanding in others. 5. Knowledge-building discourse is fostered in ‘democratic’ environments where the teacher is no longer the arbiter of truth. Marginalia explicitly aims to support more effective collaborative learning than generic forums software does. It also draws on principles from multi-media, self-regulated learning, and motivation. The annotation/highlighting tool can be seen as a tool for self-regulation: it allows learners to select out important information. Annotation features provide strategies for the reader to retrieve and review messages in a potentially meaningful and efficient way. Multimedia principles have been taken into account in the design process; of special interest is how the annotation tool may help learners reduce the cognitive information overload imposed by multiple messages in multiple threads across time (Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995; Hewitt, Brett & Peters, 2007), decreasing the complexity of following online divergent discussions; on the other hand, the potential to overburden the learner with too many features, creating cognitive overload, has also been considered (Bures, Abrami, & Schmid, in press; Dillenbourg, 2002). Marginalia was also designed in keeping with motivational principles. Much research has promoted the idea of creating and supporting a knowledge-building community through making the thinking and contribution of participants more visible (Hewitt, 2004) which may increase the interest students feel in the online discussion and how much they value it. Making it easy for participants to respond to multiple messages supports students and instructors acknowledging the contributions made by others. The annotation tool also makes it easy for students to see what other students and the teacher think of their own writing, and students have reported appreciating this [REFERENCE REMOVED for blind coding]. When a student sees other students or the teacher highlight or comment upon his/her own work, this shows him/her that his/her contribution was valued and used by others in the process of co-constructing knowledge. Other possibilities include scaffolding motivational aspects of the environment, such as helping students self-evaluate their own participation. Considering how challenging encouraging consistent use of the feature was, attention needs to be paid to motivational aspects of Marginalia. We hypothesize that students at different developmental stages will make use of knowledge tools differently and will benefit from them differently. It is important to take into consideration the developmental level of intended user when designing features to add onto software. For example, the labeling feature may be more appropriate at a younger less expert level, but becomes unnecessary; annotating may become more useful as students are older. Although it does structure and scaffold aspects of interaction, the current version of Marginalia does not rely on all the important principles of collaborative and cooperative learning. Online learning allows teachers to assess students individually based on collaborative processes they engaged in, creating individual accountability, but there is currently no means by which to create structures of positive interdependence. A future version may incorporate these principles. Furthermore, uses of Marginalia may need to be more carefully explained and supported for teachers and students to insure enhanced motivation and engagement. Beyond Marginalia: IceCream Marginalia could be used to more effectively address research-based principles of design; it would be interesting to explore how these could impact on student engagement. Some features could be integrated into the software as is the annotation feature, and others could be external (i.e. in the form of instructional design templates drawing on cooperative or collaborative learning principles). Online discussion forums are changing in nature: once computer conferencing, now they’re embedded in ‘course-management software’. Web-based discussion forums are also integrated more and more with syncchronous tools such as chat or social media tools. This is one important consideration as we consider how to go beyond Marginalia. A second important consideration is how to design the software to be developmentally appropriate. Students at different stages have needs of different levels of scaffolding. Generic open-source web-based course management software such as Moodle is growing in popularity and is in use across universities in North America, and is in increasing use at the high school levels. This type of software is for adult learners. There are no flavors; it is ‘one size fits all’ design. Elsewhere, we have designed electornic portfolio software to support students’ literacy with three levels for early elementary, later elementary, and secondary; recently, we have developed a foruth level for pre-service and in-service teachers. This level has less scaffolding and different features intetegrated to reflect adult learning motivational differences. [Name removed for blind coding] was designed systematically drawing on research-based evidence, and has different levels to suit developmental stages. This gave more focus to our thinking about ‘beyond Marginalia’, leading us to believe that a forums-based software should be configured quite differently depending on the developmental level, and that the level changes not only which scaffolds are included but the place of the scaffolds themselves in the larger picture. Currently we are designing a discussion-based software with different levels; the software will be called IceCream and the different flavours will offer dramatically different scaffolds and supports for students. We draw on the open-source code supporting Moodle, a popular web-based forum software and are developing plug-ins which integrate with Moodle that consist of inter-related integrated features and collaborative scripts/instructional templates appropriate for the different targeted developmental levels (i.e. high school, university). Each developmental level will be associated with a flavour (a plug-in) which contains features and instructional templates. We will further integrate the discussion software with tools supporting synchronous chat (google talk), searching and retrieval of information from the Internet (google reader), and twitter. Features A variety of features will be integrated into the software, but feature use will be designed to be specific and contextualized. This will be promoted by developing collaborative scripts and instructional templates which provide structure and guidance in a different way than features do. Instructors and to some extent students will need to find the balance between structure from instructional design versus structure from the features. The features will be designed to support instructor and learner control. In the first instance, Ice Cream will allow instructors to customize the tools available, so that they can design course features to meet their goals of promoting interaction in the course. In the second instance, Ice Cream will allow students choices as to which tools to draw on, and how to learn, collaborate and interact, ideally promoting their meta-cognitive skills. Some research has explored how the software supporting online discussions could be designed more effectively to support pedagogical means through features such as annotations, tags, and sentence openers. The use of social annotation features which allow students to write comments on the margins of online messages as they can an article or a book has been suggested as one strategy to address the problem of reflection in online discussions. Such tools may help learners review messages and engage more deeply in the online discussion. Similarly, when students tag their own and others’ messages, they are more easily able to retrieve messages in a meaningful way. Both annotation and tagging tools involve students reading messages and adding a layer of meaning or interpretation which should permit easier more meaningful retrieval. The proper uses of tags and annotation mean the learner has made an active attempt to extract key ideas and concepts from text, a facet of developing the personal meaningfulness of new content. Other features may help students write better messages by providing commonly used phrases such as “My hypothesis is….” or “Building on your point”. Students can choose from a variety of ‘sentence-openers’ tailored to the type of activity. So for example, in a science class the scaffolds would be different than in a literature class, helping students learn the ways of thinking and expression appropriate to the domain. Some evidence exists that sentence-openers or ‘in-line labelling’ relates to the critical thinking exhibited in online dialogue. They may help students focus their messages effectively. The use of tags, annotations, and sentence openers involves students thinking about the meaning of their own and others’ messages in a form of meta-cognitive activity. This may influence how well they write and how well they read messages. These features can be combined with search and retrieval functions that allow the students to view the messages from a different perspective (i.e. look at all annotations in context, or look at all sentence openers in context). Some features included (to be modified during the design and development process): Features Designed to Support Reading: 1.Tagging (message tagging). 2. Highlighting parts of messages (drawing on Marginalia). 3. Annotating parts of messages in the margins of messages (drawing on Marginalia). Annotations can serve multiple purposes; instead of being a general annotation feature, it could vary depending on the teacher and the design of the activities i.e. it could appear as a key idea column not a general annotation column. 4. A recommend button (Hewitt) where students say why they are recommending that part of the text or the message overall. Features Designed to Support Writing: 1. General in-line labels or sentence openers such as “Building on your point.” 2. Subject-specific or activity-specific sentence openers such as “; sentence openers (labels which are inserted within message). Features Designed to Support Reading, Writing & Developing Understanding (Synthesis): 1. Search, retrieval and display features drawing on tags, highlights, annotations, sentence openers, labels, and recommendations. 2. Visual ways to view the messages and how they inter-connect. 3. Ways to view one’s participation over time and one’s ‘influence’ (the role of one’s messages in the discussion and how the messages connect to other’s). 4. Concept maps. 5. Summaries or weaving contributions. Features Designed to Support Meta-Cognitive Skills: These features will be designed to encourage planning drawing on Zimmerman’s model of selfregulated learning as involving goal-setting, strategy-selection, and self-assessment (2002) and Pintrich, drawing on the design of ePearl. 1. Goal-setting. 2. Strategy selection. 3. Reflection (including assessment of one’s own learning). Students at the younger levels would need more features to support goal and strategy selection, but assessment and reflection would be at all ages. Collaborative Scripts and Instructional Templates: Collaborative scripts and instructional templates could include: Cooperative structures (ways to foster effective collaboration including strategies for positive interdependence, individual accountability, and promotive interactions); guidelines and templates about online activities drawing on Steiner’s collaborative learning tasks; guidance as to how a specific feature might support certain activities. The long-term vision would be to have a cafeteria of choices, reflecting a variety of teaching/learning approaches and contextual factors. In addition, the software will allow for easy integration with google tools supporting synchronous chat (google talk), google docs, and google reader, as well as twitter and other social media as appropriate. With the evolution of Web 2.0 technologies, tools which allow users to ‘save’ gems from the internet for later retrieval such as through highlighting and tagging are on the rise. But many users do not habitually participate in the collaborative tagging process even in informal settings -- the motivation for using most of these tools such as tagging is the social aspect of sharing and seeing other people’s contributions (Ames, XXXX). We found this to be true with the use of the annotation tool in Marginalia within the university-context [Reference removed]. Conclusions This work is at the beginning of IceCrea (this next phase in development), and the end of our work on Marginalia. References