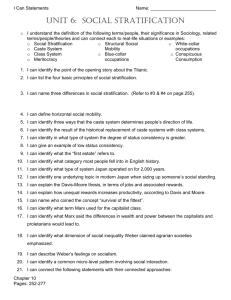

Stratifying Chapter 5 Powerpoint

advertisement

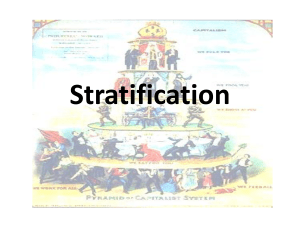

Being Sociological Chapter 5 Stratifying Social Stratification • Inequality is something we see on a daily basis and that exists in every society. • These layers of inequality reflect one of the most important and widely used concepts in sociology – social stratification. • Social stratification refers to the systemic ways that groups of people are organized unequally within a broad social hierarchy. However, as noted by Kerckhoff (2001), social stratification ‘describe[s] both a condition and a process’ (p. 3). This hierarchal characterization of society is a process in that it does not simply exist. Rather it is something that has been created, is maintained, and perpetuated by society’s elite membership. Theoretical Underpinnings: Karl Marx • Marx believed that divisions in society emanated from a society’s material conditions – from the basic materials of subsistence that with society’s evolution would be transformed into widely produced consumer items. • Marx argued that these sub-structural conditions of production determined imbalanced super-structural, ideological relationships within a society’s institutions, such as the family, religion, government, and of course work. The entire process is something Marx called historical materialism. The bourgeoisie and the proletariat • For Marx, these imbalanced relationships within and across varying institutions were accentuated by social class differences. • The bourgeoisie are the elite members of society who own and control productive resources, along with the technology used to churn resources into commodities. The bourgeoisie’s position as owners of the means of production yields them additional social privileges, including power over distribution of profits that perpetuates their higher standard of living over the working class, or proletariat, who in contrast can only offer their physical labour as currency to the bourgeoisie (Muntaner, et al., 2003). • Marx contended that with the ongoing development of industrial capitalism, class divisions became increasingly oppressive; • Upper-class members (bourgeoisie) will always utilize their control over the means of production to assert their dominant position over lower-class members (proletariat) by dictating: • the proletariat’s tangible workplace conditions (e.g., determining breaks, working hours, safety measures, whether or not work is done in isolation); • how dominant and submissive workplace relationships are established (e.g., through surveillance of workers, possible punishments for worker insubordination, transparency of management); • how industrial products and profits are dispersed across society (e.g., once a product’s value is determined, can members of the working class even afford to purchase it?) (Giddens, 1973). • Marx would purport that the inequalities we view are manifestations of historical materialism, of the fact that those situated atop society’s socially stratified ladder are fortunate to own and control the means of production. • It is vital to mention that despite Marx’s cynical outlook on capitalism, he was an optimist, believing that the working-class proletariat would realize their collective exploitation at the hands of the bourgeoisie. In doing so, they would develop a collective sense of class consciousness, revolt against their oppressors and create a more egalitarian society without extensive social stratification. Theoretical Underpinnings: Max Weber • Weber would agree with Marx that class is an important component in understanding social stratification; • However, Weber would argue in more extensive terms that social stratification emerges from three social constructs – class, status, and party. • Class status for Weber is decided by more than one’s ownership over the means of production. Instead, class status carries three subcomponents: • class groups have similar economic interests, material wealth, and opportunities for income; • these similar interests, levels of wealth and income opportunities provide members within class groups with comparable life chances; • a class group is characterized by labour market conditions (Gerth & Mills, 1946). • Ownership over the means of production is not essential for Weber, though he felt that one’s skill level within an occupational field was an influential class aspect. • Class status for Weber is constructed with more complexities. Moreover, class is accompanied by two additional components – status and party. • Status for Weber refers to the honour or prestige one carries within society. Status provides access for individuals to enter certain social circles, and according to Weber, individuals can plan strategically to move up (or down) a stratified society by altering their status. • Methods of increasing one’s status may involve wearing certain clothing styles, engaging in certain leisure activities (e.g., playing golf), or even marrying someone whose family comes from an upper-class background. Such activities can ostensibly enhance a person’s reputation and help boost their socially stratified position. • The final component of Weber’s social stratification model is party (or ‘power’). • This means, essentially, the ability of someone to influence others. • Weber argued that power was exerted most effectively through an organized rational order, carried out through bureaucratic procedures that have become entrenched in modern society. • This involves the ability of those with power to manage those organizations that can physically enforce a leader’s will – police, military, private security forces. Moreover, if a particular group commands power over multiple bureaucratic institutions (e.g., governmental, educational, religious), this group’s chances of dominating other, larger groups increases substantially. • Weber felt that power administered through engrained bureaucracy was the most significant. • Unlike Marx who felt the working class could and would revolt against the bourgeoisie, Weber believed with increased modernization comes thicker bureaucracy, which in turn decreases the chances of large groups in the bottom tiers of society from moving up (Collins, 1975). • In short, modernity cements social stratification and would ultimately impede working class members from challenging the social system. Global Social Stratification • A related concept is socioeconomic deprivation, ‘defined as a state of observable and demonstrable disadvantage relative to the local community or the wider society or nation to which an individual, family or group belongs’ (Salmond et al., 2006, p. 1477). • When a group within a given context notices its economic shortcomings in comparison to another group(s), socioeconomic deprivation occurs. • A related term is relative deprivation, which refers more generally to an emotional feeling of being deprived, not due to objective conditions, but because of direct comparisons made with other reference groups (Subramanyam, Kawachi, & Subramanian, 2009). Socioeconomic deprivation refers to the collective feelings that tend to emerge when social stratification is extensive, when a severely deprived group sees others in nearby areas enjoying far greater wealth. Stratification: Low and High Income Countries High-income countries with low levels of social stratification do exist; within these countries social stratification definitely exists, but the gap between those who are wealthy and those who are poor is not terribly extensive. Some of these less stratified countries include Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Japan. • On the other side of the spectrum are countries with great stratification. Some of these high-income countries with massive gaps between the rich and poor are the United States, Australia, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Aotearoa/New Zealand. • All these countries hold extensive wealth as a whole, but some have more social inequality than others within their respective borders. • Those countries with more stratification would likewise have more socioeconomic deprivation. Stratification and Social Problems The consistent finding in Pickett and Wilkinson’s study is that countries with low social stratification (e.g., Norway, Sweden, Japan) have far fewer social problems than the countries with high social stratification (e.g., United States, Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand). Social Stratification across the Pacific: Race • Globalization has impacted the Pacific in two significant waves: • The first occurred roughly between the years of 1850 and 1914 – a period characterized by colonial empires that saw Europeans extracting raw materials from native lands. • The second major wave of globalization impacting on the Pacific began in the early 1970s and continues presently. It is a wave characterized by free trade, a technical revolution including electronic commerce, and the enhanced mobility of capital where big business has extensive power in shaping official public policies (Firth, 2000). When examining social stratification across the Pacific, the various islands’ indigenous populations almost always find themselves collectively situated among the working- and lower-classes, which has adverse effects in other areas of life, such as physical health. Example: Maori (New Zealand) In 1996, average smoking rates for Maori were 21.2% higher than rates reported by New Zealander Europeans. The disparity was even greater for women, with Maori women displaying rates 25.9% higher than European women. During the 1980s and 1990s in Aotearoa/New Zealand, social inequality widened due to neoliberal governmental policies and the loss of many working-class jobs. This had severe negative impacts on numerous ethnic communities, but especially on Maori communities: • Unemployment for Europeans (Pakeha) in Aotearoa/New Zealand stood at 3.2% in 1986, rising to 7.9% in 1992, but returning to a low rate of 3.2% in 2003. • In contrast Pacific people (non-Maori) reported an unemployment rate of 6.5% in 1986, jumping to 28% in 1991, and declining to around 15% throughout the 1990s. • Maori unemployment rates were similar to other Pacific Islanders, standing at 10.7% in 1986, rising to 25.4% in 1992, and hovering above 15% through the 1990s. A 2005 study by Barnett, Pearce, and Moon also indicates that during this period the socioeconomic disparities of unemployment and receiving governmental benefits grew, with Maori residents falling further behind Europeans. The authors write, ‘ethnic gaps have widened not reduced with Maori, and particularly Maori women, being more than twice as likely to be regular smokers than Pakeha in 1996, a gap that has increased substantially since 1981’ (p. 1517). Relative Deprivation and Smoking This study also tied in the concept of relative deprivation, noting that ‘the effects of relative deprivation on smoking were more important for Maori than Pakeha in both time periods, but especially in 1996’(p. 1518) when ethnicallybased social stratification was greater. Authors of the study surmise that increased smoking rates for Maori are a direct indicator that Maori residents were much more adversely affected by governmental welfare cuts, as well as by major job losses in forestry and transport, where a larger proportion of Maori worked throughout the 1980s and 1990s. During this timeframe of economic restructuring that was especially harmful for Maori, smoking became a more prevalent coping mechanism. • Of course not all Maori and Pacific peoples respond to stress in injurious, unhealthy ways. Proclaiming such assertions would be perpetuating especially harmful stereotypes. • The point is, when a particular group (ethnically-based or not) encounters rapid economic stress and increased relative deprivation, a greater proportion of that group will cope in unhealthy ways. Additionally, the reality of racism in an ethnically stratified society should not be dismissed. Research conducted by Harris and colleagues (2006) investigated whether or not residents from Aotearoa/New Zealand confronted racism in health care systems. The research found that Maori residents more so than any other groups studied (Pacific peoples, Asian peoples, and Europeans/Others) self-reported being discriminated against in healthcare settings, irrespective of their socioeconomic status. The authors conclude, ‘experience of racial discrimination may be a potentially major health risk that contributes significantly to ethnic inequalities in health in New Zealand, as elsewhere’ (p. 1435). Social Stratification across the Pacific: Gender • Race does not exist as the only factor in a socially stratified world. • ‘The divisions of gender and ethnicity are treated here as lying at the heart of the social because they constitute particularly salient constructions of difference and identity on the one hand, and hierarchization and unequal resource allocation modes on the other’ (Anthias, 2001, p. 368). • Collectively women are devalued in the labour market relative to male counterparts due to rigid gender role expectations. • In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the 1980s and 1990s were decades of substantial economic transformation, decades when income inequality across the country expanded immensely due to conservative policy changes that minimized worker rights. • Focusing on the subsequent decade, Pappas (2010) examined sex differences in wages for the period of 1998 to 2008: • In 1998 males had an average hourly wage of $18.00 and weekly income of $785; • By 2008 this rose to an hourly wage of $20.80 and a weekly income of $887. • Women on the whole earned significantly less. In 1998 women had an average hourly wage of $14.60, making $497 per week, with the hourly wage rising in 2008 to $17.30 and weekly earnings of $610 (p. 222). • Although Pappas found that inequality rose for both men and women (in fact more so for men) during the time period, men’s average income rates clearly remain higher than those of women. Such discrepancies may reflect an inferiorization of women’s work, thereby creating gender stratification. Health Issues, Gender and Stratification • Sarfati and colleagues (2006) studied mortality rates due to breast cancer, comparing Maori and nonPacific/non-Maori women diagnosed with the disease. They studied the rates for these two groups from 1981 to 1999 and found that as the years progressed, women from the Maori cohort showed a significantly greater increase in breast cancer mortality rates. Breast cancer mortality rates for the non-Pacific/nonMaori cohort remained stable. Research has shown that Maori and Pacific peoples have greater barriers to accessing health care and more frequently encounter inferior treatment by health care providers (Davis et al., 2006; Davis et al., 1997), not to mention Maori are more likely to run into racism in healthcare settings (Tobias & Yeh, 2007). In a socially stratified context where gender and ethnicity intersect, minority groups (‘double minorities’ who are impacted by both gender and ethnicity) can face attendant social problems that have grave consequences. Conclusion • As can be seen, social stratification comes in many forms and continues to evolve over time. Today social stratification is typically considered as it relates to layers of socioeconomic inequality. • Social disparities are tied not only to social stratification, but also to the feelings people tend to hold when noticing their deprivation relative to others – a social phenomenon that exists across the globe. • The question then remains, what social policies can be created to promote socioeconomic equality, decrease social stratification, and create a healthier society for all, irrespective of race, gender, or any other social status. Discussion Points • Think about your peers in class and across your university setting. How do you think your family’s position in a socially stratified society has affected your university experience thus far compared to some of your peers? What kinds of trends do you notice with regard to which students work, and why they work? • Student debt is becoming an increasingly serious issue for university graduates. How might student debt affect a recent graduate’s position in a socially stratified world? • Think about the anxieties of university life. Students have enough to worry about trying to excel in their coursework, make new friends, and simply fit in. This chapter has covered the ways that social stratification can influence physical health. How might students’ mental health, who work and/or who expect to have high student debt, be further influenced by relative deprivation, as they compare themselves to others? What can be done about this by university services, if anything?