The-Problem-of-Induction

advertisement

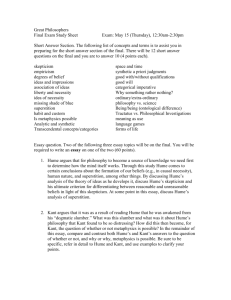

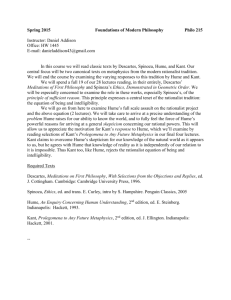

The Problem of Induction REVIEW Topics So far in class we’ve discussed the following philosophical questions: • What is (the essence of) knowledge? • Is knowledge possible? • Is knowledge of other minds possible? Other Minds Last time we considered the problem of other minds: how can we know that other people/ animals have minds and mental states, and how can we even conceive of the minds and mental states of others? Solutions to the Problem of Other Minds We considered 3 potential solutions: 1. We know that other people have minds by reasoning from analogy with our own mind. 2. We know that other people have minds, because mental states are a kind of behavior, and we can observe behavior. 3. We know that other people have minds in the same way we know electrons exist: it’s the best explanation for what we observe. Analogy The biggest issue facing the analogy solution to the problem of other minds was that it tries to argue from what is true in one case (our own mind) to what is true in every case (everybody else’s mind). This isn’t usually a good inference (what is true at my house, or in my country is not necessarily true in every house or every country), and there’s no reason to think the mind is unusual in this regard. Behaviorism Behaviorism has a truly unimpeachable solution to the problem of other minds. Unless we are global skeptics and don’t believe we can even know about others’ behaviors, then of course (if behaviorism is true) we can know about other minds. The biggest problem for behaviorism was that it is so radically implausible: one and the same belief can lead to radically different behaviors, and identical behaviors can be produced by radically different beliefs. Abduction On the abductive strategy, we don’t take behaviors as being identical to mental states, we take behaviors as evidence for people’s mental states. The best explanation for people’s behaviors is that they have a complex array of mental states that cause them to act in certain ways (i.e. functionalism or computationalism is true). The biggest problem here is that it doesn’t suggest how we can know that others have conscious inner mental lives. Today Today we’ll be considering another variety of local skepticism: induction skepticism. The basic problem is that we are only directly aware of things we have observed. If we want to know about things we haven’t observed (for example, future things), we must infer how they are from how the observed things are. But how do the observed things tell us anything at all about the unobserved ones? INDUCTION Kinds of Inference C.S. Pierce (1839-1914), an American pragmatist philosopher (in fact, the founder of pragmatism), was the first to divide inferences into three types: • Deductive • Abductive • Inductive Jars of Balls Jars of Balls Imagine that we are reasoning about a jar full of a mix of red and black balls. For any ball it can have one of three features (or their opposites): • J = it is in the jar • S = it is part of a random sample of balls taken from the jar • R = it is red Deductive Arguments A deductive argument (also known as a logically valid argument) is an argument such that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true; the premises can’t all be true while the conclusion is false; if the conclusion is false, at least one of the premises must also be false. Deduction Example Everything in the jar is red; this sample is taken from the jar; so everything in this sample is red. [Rule] All J’s are R’s. [Case] All S’s are J’s. Therefore, [Result] All S’s are R’s. Abductive Arguments An abductive argument, unlike a deductive argument, is ‘ampliative’: the conclusion goes beyond what is contained in the premises. Abductive arguments are also called ‘inferences to the best explanation.’ We observe some phenomenon, think about all the different ways it could have been produced, and conclude that it was produced in the way that is most plausible, best fits with our other theories, etc. Abduction Example Everything in the jar is red; everything in the sample is red; so the sample came from the jar. [Rule] All J’s are R’s. [Result] All S’s are R’s. Therefore, [Case] All S’s are J’s. Generalized Abduction X% of what’s in the jar is red; Y% of what’s in the sample is red; so the sample came from the jar. [Rule] X% of J’s are R’s. [Result] Y% of S’s are R’s. Therefore, [Case] All S’s are J’s. Inductive Arguments Inductive arguments are also ‘ampliative’ in that the truth of their premises does not guarantee the truth of their conclusions. Inductive arguments reason from what’s true of a sample, to what’s true of the population as a whole. Polling is an example of induction, as are inferences from past experience to future experience (since what’s past is only a sample of what happens). Induction Example This sample is taken from the jar; everything in the sample is red; so everything in the jar is red. [Case] All S’s are J’s. [Result] All S’s are R’s. Therefore, [Rule] All J’s are R’s. Generalized Induction This sample is taken from the jar; Y% of what’s in the sample is red; so X% of what’s in the jar is red. [Case] All S’s are J’s. [Result] Y% of S’s are R’s. Therefore, [Rule] X% of J’s are R’s. Enumerative Induction A common form induction takes is what is known as enumerative induction: a1 is F and G a2 is F and G … an is F and G Therefore, everything that is F is G Example of Enumerative Induction Fruit #1 is a durian that smells bad. Fruit #2 is a durian that smells bad. … Fruit #563 is a durian that smells bad. Fruit #564 is a durian that smells bad. Therefore, All durians smell bad. Need Not Infer to a Rule Fruit #1 is a durian that smells bad. Fruit #2 is a durian that smells bad. … Fruit #563 is a durian that smells bad. Fruit #564 is a durian that smells bad. Therefore, Fruit #565, if it’s a durian, will smell bad. “Generalized Deduction” Another form that induction can take is not often discussed by philosophers: it’s the ‘generalized’ form of the deductive argument: [Rule] X% of J’s are R’s. [Case] All S’s are J’s. Therefore, [Result] Y% of S’s are R’s. Example 90% of French people like to eat snails. Pierre is a French person. Therefore, Pierre likes to eat snails. Maybe this isn’t induction? It’s definitely neither deduction nor abduction. HUME’S PROBLEM OF INDUCTION David Hume (1711-1776) Hume David Hume was a Scottish Enlightenment thinker (other notables include the economist Adam Smith, the poet Robert Burns, and the philosopher Thomas Reid). He is widely regarded as one of the two greatest Western philosophers after Plato and Aristotle (the other is Kant). He wrote his most important work, the Treatise on Human Understanding, when he was only 26 years old. British Empiricism Hume is often grouped with John Locke (16321704) and George Berkeley as a British Empiricist. The empiricists believed that all ideas came from experience, and that all knowledge came from experience. Empiricism is thus a sort of local skepticism: it’s the view that knowledge about things that cannot be experienced is impossible– and, additionally, it is impossible to even think of things that can’t be experienced. Impressions vs. Ideas Hume begins Section II of the Enquiry by observing that remembering or imagining a sensation is like perceiving that sensation, but never so like as to be confused with actually perceiving that sensation. Hume calls the mental state one is in when one is actually perceiving some sensation an ‘impression’. He calls the mental state one is in when one remembers or imagines a sensation an ‘idea’. Humean Empiricism Hume’s version of empiricism says that all simple ideas are copies of simple impressions. (The restriction to simple ideas and simple impressions is a nod to the fact that we can have a complex idea, like an idea of a golden mountain, without ever having had an impression of a golden mountain.) Arguments for Humean Empiricism 1. By introspection we can see that all our ideas are either simple, and always attended by a prior impression of which they are copied; or complex, and analyzable into such simple ideas. 2. People who are blind or deaf have no ideas of colors or sounds, respectively, and that people who have never tasted wine or felt anger have no ideas of such sensations or emotions. Hume’s Challenge If there is a counterexample to Humean empiricism (a simple idea that is not derived from a prior sense impression), Hume challenges his reader to produce it. The Missing Shade of Blue Infamously, Hume then goes on to produce a counterexample himself: the missing shade of blue. Hume wants you to imagine that you have never seen one particular shade of blue (no impression of it). But then you are presented with a sequence of all the other shades, with the missing shade removed. The Missing Shade Missing Shade Counterexample Now you still have not ever had an impression of the missing shade. However, Hume thinks that when you see the sequence of other shades converging on the missing one, you will be able to come to an idea of it. So you can have an idea that is not copied from any impression. The Tribunal of Experience At the end of Section II, Hume proposes what Reid later derisively called the “tribunal of experience.” Whenever someone purports to talk about something (say, justice) we ask a series of questions: Is the idea of justice simple or complex? The Tribunal of Experience If it is simple, what impression is it copied from? [If there’s no impression, there’s no such thing as justice.] If it is complex, what are its simple constituents? What impressions are those simple constituents copied from? [If we can’t find the impressions, then there’s no such thing as justice.] Division of Types of Knowledge Hume divides all human knowledge into two types: knowledge of logical truths (relations of ideas) and knowledge of matters of fact. Knowledge of relations of ideas is logical or mathematical. It is certain, and it is a contradiction to deny any true relation of ideas. Logical Truths The way Hume is thinking, a logical truth is something that you cannot even imagine is false. You can’t, for example, imagine a case where you have two cats on the left, 10 cats on the right, yet more cats on the left than there are on the right. There’s no problem with knowing how they’re true, because you can never even suppose them to be false. Matters of Fact Knowledge of matters of fact divides into two further subcategories: (a) the immediate testimony of the senses, and of memory; and (b) knowledge inferred from such testimony. I’ll reserve the expression ‘knowledge of matters of fact’ for the second type, that is, not the immediate deliverances of the senses or memory. This is how Hume uses the expression. Matters of Fact = Unobserved Facts Thus “matters of fact” are the unobserved things that we ordinarily think we know about. We know that people are now living in Australia, though we can’t see them, we know that tomorrow, the sun will come up, even though we haven’t yet experienced what happens tomorrow. The Problem of Induction The problem of induction is thus the problem of justifying our beliefs in matters of fact. It’s clear that our sense experience justifies us in our beliefs regarding observed phenomena. But what about our sense experience (or logic and mathematics) justifies us in believing matters of fact? Not Justified by Logic Alone No matter of fact is a logical truth (this is definitional). That is, it is possible to imagine that there are no people in Australia, or that the sun will not come up tomorrow. However, maybe matters of fact are the deductive consequences of our sense experience (plus maybe some logical truths as well). Not Justified Deductively Matters of fact are not arrived at by logical deduction. If we could reason deductively from all our past sense experience + all our knowledge of logical and mathematical truths to conclude a certain matter of fact, then it should be contradictory to imagine our past experience being the same, but the matter of fact coming out differently. Not Justified Deductively For example, there’s no contradiction in supposing that the sun has risen every day of our past experience, but the sun won’t rise tomorrow. This is a possible course of events. This means that there is no deductive argument from our past experience to the conclusion that the sun will rise tomorrow. Because in a deductive argument, it’s impossible that the premises are true, and the conclusion is false. Justified by Cause-Effect Reasoning Hume therefore concludes, “All reasonings concerning matter of fact seem to be founded on the relation of cause and effect.” Example Whenever we’re asked ‘Why do you believe that?’ about some matter of fact, we cite our knowledge of its cause, or some effect it has had on us. For example, when asked ‘Why do you believe there’s a person in this dark room?’ I might reply ‘Because I heard his voice, and people are the causes of human voices.’ How Do We Know Causal Relations? Now the question arises: how do we know causal relations? What justifies our belief in them? For example, how do we come to know that humans are the causes of human voices, or that one billiard ball striking another causes the other to move? Not Justified by Logic Alone We don’t know causal relations merely by inspecting our ideas. Adam and Eve couldn’t just look at water, for example, and know from its appearance of transparence and liquidity that it would cause them to suffocate and drown if they tried to breathe it. Similarly, you can’t just tell by looking that a particular piece of stone is magnetic. You need experience to know these things. Not Justified by Logic Alone We cannot infer causal relations on the basis of logic alone, because any cause may be consistently supposed to have different effects. It’s no contradiction to think that if ball A strikes ball B, ball B doesn’t move; it goes up; it goes down; it is annihilated; it turns into Bozo the Clown, etc. Justified by the Laws of Nature Maybe, we might respond, we know the causal relations because we deduce them from laws. For example, a logical consequence of Newton’s Second Law, F = ma, is that if I apply a force of 1N to a billiard ball with mass 1kg, it will accelerate at 1 meter per second squared. I know which causes have which effects because I know the laws. How Do We Know the Laws? But this only pushes the problem back. How do we know the laws of nature? Even though with, say, Newton’s laws we can deduce the motion of the ball, still Newton’s laws are not known by logic alone, but rather discovered by experience. (In fact, subsequent experimentation has shown these laws to be false). We Must Learn Them from Experience OK, so we know that we discover causal relations/ laws of nature by experience. But how exactly does our experience justify our beliefs about causal relations? Hume is going to argue that nothing about our experience justifies our conclusions about causal relations/ laws of nature. Inferring the Future from the Past We should like to reason as follows: Premise 1. In the past, water has always quenched my thirst. … [insert other premises we know] … Conclusion: Therefore, in the future, water will continue to quench my thirst. Assuming What’s at Issue To simply take arguments of this form (without the missing premises filled in) is to assume that induction is justified. But that is what is at issue: we want to know why induction is justified (why we are justified in believing unobserved matters of fact), and it is no help to be told ‘well, I’m assuming it is, that’s why.’ The Uniformity of Nature If I can’t reason in this way, all my knowledge of matters of fact will be unjustified. For I took the voice in the dark room to indicate the presence of a person, only because in the past, words have always been spoken by people. The needed premise seems to be, that the future will resemble the past. But again, how do we know this? Again, Not By Logic Alone We certainly don’t know it by logic alone, for it is no contradiction to suppose the past was one way, and the future will be entirely different. Furthermore, it can’t be a logical truth, because sometimes it’s false: As Hume says, “Nothing so like as eggs; yet no one, on account of this appearing similarity, expects the same taste and relish in all of them.” Can’t Reason from Experience Second, we can’t learn that the future will resemble the past from experience. Consider: Premise 1. In the past, later events always resembled earlier, similar events. … [insert other known premises] … Conclusion: Therefore, at present and in the future, later events will resemble earlier, similar ones. Circular Inductive Argument Again, to simply take arguments of this form (without the missing premises filled in) is to assume that induction is justified. But that is what is at issue: we want to know why induction is justified, and it is no help to be told ‘well, I’m assuming it is, that’s why.’ Circular Deductive Argument We could add in a premise to make the argument deductive. The needed premise seems to be the conclusion, that the future will resemble the past. No Deductive Argument at All And we cannot find a non-circular premise among the things we believe about observables + logic that would make the argument deductive. Given what we believe about observables + logic, it is always possible to deny the conclusion of an inductive argument (“the sun won’t rise tomorrow”). But if the conclusion followed deductively from what we believed about observables + logic, this would be impossible. Do Laws Help? Would it help if we moved to a formulation regarding laws? Maybe our past experiences justify us in believing in a certain law of nature, and that law then justifies our causal claims (water quenches thirst) and our predictions about the future (water will quench thirst) Inferring the Future from the Past Premise 1. In the past, water has always quenched my thirst. … [insert other premises we know] … Conclusion 1: Therefore, it is a law that water drinking is followed by thirst quenching. Conclusion 2: Therefore, in the future, water will continue to quench my thirst. Abductive Argument? Here it’s possible to deny that the inference from Premise 1 to Conclusion 1 is inductive and to deny that it’s deductive. The inference is abductive: the best explanation for the regularity of the past was that it is a law of nature that water quenches thirst. Since it is a law of nature, we can conclude (Conclusion 2) that in the future water will quench thirst (laws are true always and everywhere). Does It Work? First, it’s not clear that this sort of abductive argument is a good one. Something like a law that enforced this regularity in the past may in fact be the best explanation for the regularity in the past. But we haven’t observed any regularity in the future. Does It Work? For example, suppose everyone you observe in Hong Kong drives on the left side of the road. It might make sense to infer that there is a law of the road in HK that everyone should drive on the left. But it wouldn’t make sense to infer that there is a law of the road everywhere that everyone should drive on the left. Wouldn’t It Overgeneralize? Suppose in the past that no one has ever made a stinky tofu pizza. Surely it doesn’t follow that there is a law of nature: stinky tofu pizzas cannot be made. Regularities in the past don’t always suggest laws. So if we’re going to maintain the abductive inference from Premise 1 to Conclusion 1, we have to say why this case is special. Conclusion Hume denies that any species of inductive inference (from the observed to the unobserved), such as causal inference, can be justified. It can’t be justified inductively on pain of circularity. It can’t be justified deductively, because we can always deny the conclusion of such an inference. And it can’t be justified by an appeal to laws, because the evidence only supports laws concerning the observed entities, not laws concerning the unobserved ones. HUME’S SOLUTION The Association of Ideas Hume proposes that there is a universal, innate mechanism in the mind that connects ideas together. He calls this a ‘principle of connection,’ but don’t be misled: it is a mechanism, not an abstract principle. Arguments for the Mechanism 1. If you pick up a serious book, say a philosophy book, any particular sentence will be related to the sentence before it, and related to the sentence afterward. 2. The same thing is true even in more free-form conversations, and in dreams. Arguments for the Mechanism 3. Even when it seems not to be true in conversation, if you stop and ask someone who has just brought up a new topic, he will be able to provide you with the connection to the old topic that led him to think of the new one. 4. Unrelated languages tend to have words for the same complex ideas. So there is probably some universal, innate mechanism that connects the same simple ideas into complex ideas among all people. Three Ways to Get Connected There are, says Hume, only three ways ideas get connected to one another by the mind: • 1. Resemblance • 2. Contiguity in place or time • 3. Cause/ effect There could be more, but Hume can’t think of any. Proof that the Mind Connects These 1. Resemblance: if we see a picture, we think of the person it is a picture of, because the picture resembles her. 2. Contiguity in place or time: if we’re talking about one apartment in a building, we naturally think of the others. 3. Cause/ effect: if we think of a wound, we’re likely to also think of the pain it causes. Brute Inductive Mechanism We may now wonder why the mind connects two events A and B causally, when (if Hume is right) there is no rational basis for belief in causal relations. Hume’s solution to this problem is that there is no rational reason why the mind behaves this way, that’s simply the way it’s built. Not All Behavior is Rational Sometimes there is no good reason to behave in a certain way, and we still do it. Sometimes we even know that there is no good reason, but we still do it. For example, we might take methamphetamines, despite our knowledge that our habit is killing us– not because we have a good reason to, but because that is how we are built– we are addicted and cannot stop. Induction is Brute, Not Rational Hume’s view of inductive inference is like this. He thinks that we do it out of “habit” or “custom” (though he might better say “compulsion”). Even if we recognize that inductive inferences are never justified, we cannot help but continue to reason as though they were justified. Hume’s Model: Belief Hume is going to present a model of the mind on which this picture is true and plausible. He begins by asking, what is it to believe something? Belief is not a further idea that, when we add it to another idea, makes the latter into a belief. For the mind is free to combine any of its ideas in any way it chooses, but it is not free to believe whatsoever it wishes. Belief = Vivid Idea Therefore, belief is a sentiment or attitude towards an idea. Hume says that this sentiment cannot be described to anyone who doesn’t have it (just as red can’t be described to a blind man), but we can analogize it to a “more vivid, lively, forcible, firm, steady conception of an object.” These are the aspects of belief, says Hume, that make it more influential than imagination; of more apparent importance; and able to govern our actions. Causal Reasoning What it is for the mind to have the habit of inferring B from A, as in causal reasoning, is for the force or vivacity of A to be conferred on B. Thus when we have an A-impression (very vivid), we are led to a vivid B idea, and thus believe B. Causation Preserves Vivacity Hume thinks that the mind is led to associate two things F and G causally when they are “constantly conjoined”– that is, when every F in the past has been G (for example, every durian has been smelly, or every cup of water has always quenched my thirst. Association (in the causal way) preserves vivacity, so that if A and B are causally associated, and I believe (vivid image) A, then I will believe (vivid image) B. Resemblance Preserves Vivacity But is it only causal reasoning that is vivacity preserving in this way? Hume argues that all the principles of association operate similarly. Resemblance. Suppose I see a picture of my friend X. Since the picture resembles X, I am led to an idea of X by the principle of resemblance. Is this idea more vivid than usual? Hume says yes. We can observe that all our X-directed emotions grow stronger on confronting his picture. Contiguity Preserves Vivacity The importance here is that the transition is vivacity-preserving. If I weren’t looking at my friend’s picture, even if I thought of it and this led me to think of him, I would not have a vivid idea of my friend. Contiguity. Suppose you’re on a train, approaching home. Your thoughts of home get stronger and more forceful as you approach the surrounding areas. Hume’s Associationist Mind 1. We have vivid impressions of what’s going on in our immediate environment. 2. When any of these impressions are resembling, contiguous, or constantly conjoined, our mind associates the ideas copied from them. 3. When subsequently confronted with a vivid impression of something, the vivacity-preserving associative mechanisms cause us to think of associated ideas vivaciously. 4. Since belief = vivid ideas, our impressions lead us to beliefs about things not immediately present to our senses. Reasons to Think Induction is Brute 1. Conscious reasoning is slow, and our survival requires quick causal inferences. 2. Infants aren’t rational, but they still must learn. 3. Conscious reasoning is liable to error, whereas brute mechanisms never run astray. (Hume doesn’t mean factual error—induction often reaches the wrong conclusion. He means error in function, not drawing the conclusion one is supposed to draw from the experiences one has, whether this conclusion is right or not). Conclusion There is no reason why (rationally) we should reason inductively. However, our minds are associative and thus there is a reason why (causally) we reason inductively. KANT’S SOLUTION Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) Immanuel Kant Immanuel Kant was a German philosopher whose principal concern was to surmount the skeptical challenges offered by thinkers like Berkeley and Hume. Kant often vies for Hume for the title of greatest non-Ancient-Greek Western philosopher. Kant credited Hume with awakening him from his “dogmatic slumber.” Phenomena vs. Things in Themselves Kant thought that the phenomenal world (the world that we experience) was the joint product of “things in themselves” (external objects out there) and principles of the mind. The Mind Structures Reality The mind thus imposes a certain structure on the phenomenal world. Kant thought, for instance, that things in themselves did not exist in space and time, but the mind structured all experience so that the phenomena were in space and time. Preconditions of Experience We could therefore know independently of experience that everything was located in space and time even though this is not a logical truth. Hume missed a third way of justifying beliefs: 1. as logical truths, 2. inferred from experience and, crucially, 3. as a precondition imposed by the mind on experience itself. Euclidean, Newtonian Structure Kant further thought that “space-time is Euclidean” and “Newton’s laws are true” are preconditions the mind places on experience. The mind orders all of its experiences so that they conform to a Euclidean, Newtonian structure. Thus we can know that in the future, Newton’s laws will hold, because experience itself is impossible without those laws. The Problem with Kant Kantian ideas were very popular until about the early 20th Century, when it was discovered that space-time was not Euclidean, and that Newton’s laws were false at speeds approaching the speed of light. Either Kant was wrong that the mind imposes a certain structure on reality, or he was wrong to think that we could find out what aspects of the structure were contributed by the mind. POPPER’S SOLUTION Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994) Karl Popper Popper was an influential philosopher of science– perhaps the most influential of the 20th Century. He proposed that Hume was right, but that we didn’t need induction anyway. Induction Not Needed According to Popper, no scientific theory, hypothesis, law, or causal claim can every be justified or shown to be probable (or more probable than its competitors). Induction is not a source of justification, and we don’t need it to be. Falsifiability The important notion in science for Popper is falsifiability– when it is possible to show that a theory or hypothesis is false, by observing a counterexample to it. For example, “all durians are smelly” is falsifiable, because it is possible (in theory) to observe a durian that is not false. We should adopt the “strongest” scientific theories, and then try hard to falsify them. Those that survive, we keep. Strength A theory is strong when it is easier to falsify. Thus “the sun will continue to rise” is stronger than “the sun will continue to rise until 21 December 2012” because to falsify the former, you have to observe just one day out of them all when the sun doesn’t rise, whereas to falsify the latter, the sun needs to not rise on one particular day, which is obviously less likely. Corroboration A theory is corroborated when we have tried many times to falsify it, but have not yet succeeded. So the theory of general relativity is very well corroborated, because we have spent billions of dollars and billions of person-hours trying to test its predictions, and so far it has survived all the tests. Rational to Prefer, Not Justified We should rationally prefer the strongest (most easily falsifiable) and most corroborated theories we can find, according to Popper. However, just because it is rational to prefer them does not mean they are supported by the evidence. According to Popper, the problem of induction shows that such theories are never supported by the evidence. Problems Popper focused on science, and his philosophical approach just doesn’t seem right for everyday life. It’s not merely that we should rationally prefer the theory “rat poison is deadly to eat,” but that we are justified in not eating rat poison, because of its past record in killing those who ate it. What’s So Great about Falsifiability? Furthermore, while Popper attacked theories he thought weren’t falsifiable (psychoanalysis, for example) as being unscientific, it seems as though lots of unfalsifiable claims are within the bounds of science: “there are durians that are not smelly” cannot be falsified. Smelly durians are compatible with the claim (others might not be smelly), and non-smelly durians are also compatible (it’s what the claim claims). SUMMARY Today’s Question “Is it possible to know (non-logical facts) about unobserved things?” Hume against Induction Hume famously argued that the answer was “no”: • All of our inferences about unobserved instances (matters of fact) require causal reasoning. • Causal reasoning is a species of induction: an inference from observed instances to unobserved instances. Hume against Induction • Induction can’t be justified by induction, on pain of circularity. • But it can’t be justified deductively either– otherwise we’d be certain of the conclusions of inductive arguments, and we never are. • We might infer laws from observed instances, and then deduce future consequences, but it’s difficult to elucidate why or how such abductive arguments are suitable. Potential Solutions In addition to the abductive inference strategy (laws are the best explanation for our past observations, and they entail what we will observe in the future), we considered three other potential responses. Hume’s Skeptical Solution Hume thought that we should accept that there is no justification for inductive inferences. He gave arguments that people are made by nature to reason inductively, and that what we took to be rational inferences were simply unstoppable brute mental mechanisms with no grounding in reason. Kant’s Idealist Solution Kant thought we knew the laws because they weren’t themselves matters of fact, but rather preconditions of experience. Since the mind contributed the laws to the phenomenal world, we could inspect our minds to know they were true. The problem with Kant’s view is its bad track record of telling us what the preconditions of experience are. Popper’s Falsificationist Solution An influential 20th Century philosopher of science, Popper argued that we could do without inductive inference altogether, unjustified or not. He claimed that we should rationally prefer strong, corroborated theories, even though they could never be justified by the evidence. This rings hollow in everyday life, and is outmoded in the philosophy of science as well.