R 2

advertisement

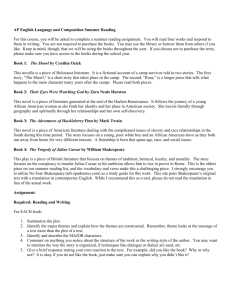

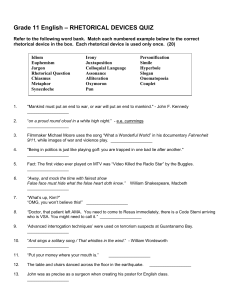

AP English Literature and Language The Language of William Shakespeare Pre-reading Notes Shakespeare’s Grammar Syntax Rhetorical Devices Usage Shift. We know what we are, but know not what we may be. - Shakespeare Syntax The arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. Syntax Part 1 The most common simple sentence in modern English follows a familiar pattern: Subject (S), Verb (V), Object (O). To illustrate this, we'll devise a subject (John), a verb (caught), and an object (the ball). Thus, we have an easily understood sentence, "John caught the ball." This is as perfectly an understood sentence in modern English as it was in Shakespeare's day. However, Shakespeare was much more at liberty to switch these three basic components—and did, quite frequently. Shakespeare used a great deal of SOV inversion, which renders the sentence as "John the ball caught." This order is commonly found in Germanic languages (moreso in subordinate clauses), from which English derives much of its syntactical foundation.1 Syntax: Part 2 Another reason for Shakespeare's utilization of this order may be more practical. The romance languages of Italian and French introduced rhymed verse; Anglo-Saxon poetry was based on rhythm, metrical stresses, and alliteration within lines rather than rhymed couplets. With the introduction of rhymed poetic forms into English literature (and, since the Norman invasion, an injection of French to boot), there was a subsequent shift in English poetry. To quote John Porter Houston, "Verbs in Old French and Italian make handy rimes, and they make even better ones in English because so many English verbs are monosyllabic. The verse line or couplet containing a subject near the beginning and a verb at the end is a natural development."2 Of course, Shakespeare wrote a great deal of work in blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter); when he wasn't rhyming, what was he thinking? Frankly, Elizabethans allowed for a lot more leeway in word order, and Shakespeare not only realized that, he took advantage of it. By utilizing inverted word orders, Shakespeare could effectively place the metrical stress wherever he needed it most—and English is heavily dependent on vocal inflection, which is not so easily translated into writing, to suggest emphasis and meaning. In his usage of order inversion, however, Shakespeare could compensate for this literary shortcoming. Syntax Part 3 Shakespeare also throws in many examples of OSV construction ("The ball John caught."). Shakespeare seems to use this colloquially in many places as a transitory device, bridging two sentences, to provide continuity. Shakespeare (and many other writers) may also have used this as a device to shift end emphasis to the verb of a clause. Also, another prevalent usage of inversion was the VS order shift ("caught John" instead of "John caught"), which seems primarily a stylistic choice that further belies the Germanic root of modern English. In the end, Houston points to "the effort to make language more memorable by deviation from spoken habits."3 This is the essence of poetry: a heightening of language (even colloquial) above that of prose, a heightening that produces an idealized, imaginative conception of the subject. Rhetorical Devices “I would challenge you to a battle of wits, but I see you are unarmed!” ― William Shakespeare Rhetorical Device Expectations: Flashcards you make. Rhetorical Devices Page 1 alliteration repetition of the same initial consonant sound throughout a line of verse "When to the sessions of sweet silent thought...." (Sonnet XXX) anadiplosis the repetition of a word that ends one clause at the beginning of the next "My conscience hath a thousand several tongues, And every tongue brings in a several tale, And every tale condemns me for a villain."1 (Richard III, V, iii) anaphora repetition of a word or phrase as the beginning of successive clauses "Mad world! Mad kings! Mad composition!" (King John, II, i) anthimeria substitution of one part of speech for another "I'll unhair thy head." (Antony and Cleoptra, II, v) Rhetorical Devices Page 2 antithesis juxtaposition, or contrast of ideas or words in a balanced or parallel construction "Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more." (Julius Caesar, III, ii) assonance repetition or similarity of the same internal vowel sound in words of close proximity "Is crimson in thy lips and in thy cheeks." (Romeo and Juliet, V, iii) asyndeton omission of conjunctions between coordinate phrases, clauses, or words "Are all thy conquests, glories, triumphs, spoils, Shrunk to this little measure?" (Julius Caesar, III, i) chiasmus two corresponding pairs arranged in a parallel inverse order "Fair is foul, and foul is fair" (Macbeth, I, i) Rhetorical Devices Page 3 diacope repetition broken up by one or more intervening words "Put out the light, and then put out the light." (Othello, V, ii) ellipsis omission of one or more words, which are assumed by the listener or reader "And he to England shall along with you." (Hamlet, III, iii) epanalepsis repetition at the end of a clause of the word that occurred at the beginning of the clause "Blood hath bought blood, and blows have answer'd blows." (King John, II, i) epimone frequent repetition of a phrase or question; dwelling on a point “Who is here so base that would be a bondman? If any, speak; for him I have offended. Who is here so rude that would not be a Roman? If any speak; for him have I offended." (Julius Caesar, III,ii) metaphor implied comparison between two unlike things achieved through the figurative use of words "Now is the winter of our discontent Made glorious summer by this son of York." (Richard III, I, i) metonymy substitution of some attributive or suggestive word for what is meant (e.g., "crown" for royalty) "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears." (Julius Caesar, III, ii) onomatopoeia use of words to imitate natural sounds "There be moe wasps that buzz about his nose." (Henry VIII, III, ii) paralepsis emphasizing a point by seeming to pass over it "Have patience, gentle friends, I must not read it. It is not meet you know how Caesar lov'd you." (Julius Caesar, III, ii) parallelism similarity of structure in a pair or series of related words, phrases, or clauses3 "And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover To entertain these fair well-spoken days, I am determinèd to prove a villain And hate the idle pleasures of these days." (Richard III, I, i) Rhetorical Devices Page 5 parenthesis insertion of some word or clause in a position that interrupts the normal syntactic flow of the sentence (asides are rather emphatic examples of this) "...Then shall our names, Familiar in his mouth as household words— Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter, Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester— Be in their flowing cups freshly remembered." (Henry V, IV, iii) polysyndeton the repetition of conjunctions in a series of coordinate words, phrases, or clauses4 "If there be cords, or knives, Poison, or fire, or suffocating streams, I'll not endure it." (Othello, III, iii) simile an explicit comparison between two things using "like" or "as" "My love is as a fever, longing still For that which longer nurseth the disease" (Sonnet CXLVII) synecdoche the use of a part for the whole, or the whole for the part5 "Take thy face hence." (Macbeth, V, iii) Usage Shift “My bounty is as boundless as the sea, My love as deep; the more I give to thee, The more I have, for both are infinite.” ― William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet Usage Shifts In the dark backward and abysm of time. Temp., I, ii, 50 That may repeat and history his loss. 2 H 4, IV, i, 203 This day shall gentle his condition. H 5, IV, iii, 63 Grace me no grace, nor uncle me R 2, II, iii, 87 no uncle. My death's sad tale may yet undeaf his ear. R 2, II, i, 16 § One part of speech is often substituted for another; this is most frequent with nouns and verbs. (See also "anthimeria" in the Rhetoric section.) § Adjectives don't always mean what they seem to say; active and passive forms are sometimes interchangeable, as are those that signify cause or effect. Wherever in your sightless (= Macb., I, v, 50 invisible) substances. There's something in 't That is deceivable (= T.N., IV, iii, 21 deceptive). Oppressed with two weak (= A.Y.L., II, vii, 132 weakening) evils, § Pronouns have irregular inflections; often the nominative case (he, she, who) is used instead of the objective case (him, her, whom). And he (= him) my husband best of all affects. Yes, you may have seen Cassio and she together. Making night hideous, and we fools of nature So horridly to shake our disposition. Pray you, who does the wolf love? M.W.W., IV, iv, 87 Oth., IV, ii, 3 Haml., I, iv, 54 Cor., II, i, 8 § Verbs don't always agree with their subjects; most frequently a singular verb is used with a plural subject. These high wild hills and rough uneven ways Draws out our miles, and makes them wearisome. Their encounters, though not personal, hath been royally attorneyed. Three parts of him Is ours already. More Usage Shifts R 2, II, iii, 4-5 W.T., I, i, 28 J.C., I, iii, 154-55 § Omission of the relative pronoun (e.g., "the woman that I love" becomes "the woman I love") is much more frequent than in modern English, being applied to the nominative case as well as the objective. I have a brother is condemn'd M. for M., II, ii, 34 to die. Besides, our nearness to the King in love R 2, II, ii, 129 Is near the hate of those love not the King. But wait… There Are More! § Double-negatives are often used for emphasis of a point. Nor never could the noble Mortimer Receive so many, and all willingly. 1 H 4, I, iii, 110 You may deny that you were not the mean Of my Lord Hastings' late imprisonment [i.e., deny that you were the mean]. R 3, I, iii, 90 Usage Shift § "That" often takes the place of "so that," "in that," "why," or "when" in certain clauses. The hum of either army stilly sounds, That (= so that) the fix'd sentinels almost receive The secret whispers of each other's watch. H 5, IV, Chorus, 6 Albeit I will confess thy father's wealth Was the first motive that (= why) I woo'd thee, Anne. M.W.W., III, iv, 14 Is not this the day That (= when) Hermia should give answer of her choice? M.N.D., IV, i, 140 What’s Your Message? Thou art done.