Introduction to Literature

advertisement

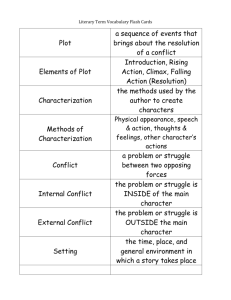

Introduction to Literature Lesson Three: Reading Short Stories Love Margarette R. Connor Outline • Short story critical terms – – – – – – – plot character setting point of view symbolism theme style, diction, irony • Biography of O. Henry Short stories aren’t as “scary” as poetry • Because they are narratives, they “look” more “normal” than poetry. • We read narratives every day--in the newspaper, in magazines, so the form looks more comfortable. “When you reread a classic you do not see more in the book than you did before; you see more in you than was there before.” --Clifton Fadiman • Fadiman was a writer, critic, editor, and radio quiz show host. He was also very influential in shaping American literary taste. • For more than 50 years, Fadiman influenced what Americans read, serving as a senior judge for the Book-of-the-Month Club A note on critical vocabulary: • Things like diction, tone, allusion and symbols can all still be important, so keep them in mind as you read throughout the course. • But we’re now going to add some new words to your critical arsenal. Plot • How a story is organized, how the author arranges events. • These events can be arranged in a number of orders: – chronological, – flashback, – even in loosely arranged views. • When we discuss plot in short stories we often talk about events building to a climax, which is the point where the crisis that has been building reaches its highest point and is somehow resolved. It comes very close to the end of the story as what follows is usually tying up the loose ends and easing us out of the world of the story. Character • These are the “people” or sometimes even the animals (like Jack London’s Buck in “The Call of the Wild”) who make up the story. • They are what make us care about the story. • How a writer creates a character is called characterization and as critical readers, we look for clues into a character through things like – – – – speech patterns, dress, possessions actions. Two important character terms: • Protagonist, or sometimes, “the hero,” though in many stories, the protagonist isn’t too heroic! • Antagonist, or the “bad guy”. The one who is the adversary of the protagonist. Setting • When and where a story takes place. • Sometimes the setting can almost become a character itself, as in Faulkner’s South or Hawthorne’s Puritanera New England. • The major elements of setting are – the time, – place and – social environment that act as a frame around the characters. • If we are sensitive to the time and place in which a story takes place, it can help us understand the character’s actions. Atmosphere • An author can also use setting to establish atmosphere, the mood a work will take. • In Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher,” the decaying house and its surroundings echo the decay of Roderick Usher’s mind. Point of view • This tells us who’s eyes we are seeing the story through, the person we call the narrator. • The narrator has a very important function, because how he or she sees things may very well color how we see things. • We have to be aware of where we are getting our information. Two different types • Third person, – has three types • First person, – has two types. Third person narrator • A non-participant in the action of the story, but sometimes the author limits the view. • Includes omniscient, limited omniscient and stream of conscious. Omniscient narrator • All-knowing. – The narrator can tell us anything that’s happening at any time in the story. – If the narrator can go into all the character’s thoughts and tell us what’s going on with their emotions and thought-process, we call that editorial omniscience. – In contrast, the narrator may only show us what’s going on in terms of the actions and words of a character, leaving us to draw our own conclusions about motive. That’s called neutral omniscience. Limited omniscient narrator • The author restricts the narrator to a single perspective of either a major or a minor character. – Sometimes the narrator can see into more than one character, especially in longer works, but the limited space of the short story form usually ensures that the author limits the narrator to one. Stream-of consciousness • Developed by modern writers. • We see the unedited thoughts of the narrator, with : – logical jumps, – fragments – fleeting thoughts all included. • The most famous example of this style is James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is indeed incredibly challenging to read. A section from Ulysses describing a funeral: • Coffin now. Got before us, dead as he is. Horse looking round at it with him plume skeowways [twisted]. Dull eye: collar tight on his neck, pressing on a bloodvessel or something. Do they know what they cart out of here everyday? Must be twenty or thirty funerals everyday. Then Mount Jerome for the protestants. Funerals all over the world everywhere every minute. Shovelling them under by the cartload doublequick. Thousands every hour. Too many in the world. First person narrator • Either a major character or a minor character, depending on how much the author wants to give away to the reader. • This is the easiest to spot, as the narrator speaks in terms of “I” Unreliable narrator • One whose views do not match those of the author. • This type of narrator is a filter, and we have to realize that there are other conclusions that we might have to make for ourselves. Naïve narrator • Told from the point of view of an innocent or a child. • An example is Mark Twain’s famous Huck Finn. – He tells us the story, but it is from a child’s point of view and as readers, we must always remember this fact. Symbolism • We discussed symbols when we went over the first lesson, and symbolism is finding the meaning of symbols. • Two different kinds – conventional – literary Conventional symbols • Widely recognized by a culture or society. • Examples are – a nation’s flag, – the Christian cross, – the Jewish Star of David, – the Buddhist cross – the Nazi swastika Literary symbols • can include conventional meanings, but they can also be used specifically by an author. • A literary symbol can be – a setting, – character, – action, – object name or – anything else in a work that functions on more than one level. Theme • The central idea or meaning of a story. • It’s the point an author is trying to make. • As simple as this sounds, it isn’t always simple finding the theme. Some help finding theme • Take a look at the title of the story. It can often point the way. • Look for details that are potential symbols. Look at names, places, things. All these can help point the way. • Decide whether or not the protagonist has undergone any changes or develops any insights into life/humans/so on. • Remember that a theme won’t be one word like love. It will be a statement about love. Style • How a writer writes. – After we’ve been reading literature a while, we can spot a Hemingway story or one by Jewett or Faulkner. – All are American writers, but all have their own way of putting things down on paper. Diction • As with poetry, this is the language a writer uses. While part of this is style, a good writer will change diction. – A countess won’t sound like a chambermaid if the writer is paying attention, unless, of course the countess was a chambermaid who “married up”. • Writers use diction to shade in characters Irony • A device that reveals a reality different from what appears to be true. • There are three different kinds of irony that we’ll discuss. Verbal irony • If my friend is very dirty from playing football, and I say, “You are looking so fresh today,” that’s verbal irony. – Very common in today’s speech. • If I mean to hurt someone with my verbal irony, it becomes sarcasm. Situational irony • Happens in literature when the reality isn’t what we think it is. – For example, in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” it looks as if the narrator has a caring husband, but through trying to cure her, he makes her worse. Dramatic irony • Occurs when protagonist says something or believes something that the reader understands is not true. – Flannery O’Connor uses this device quite a bit in her writing. • For example, in “Revelation” the white Mrs. Turpin thinks of herself as a godly woman who is better than the “niggers” and “white trash” around her. • As readers, we see that her statements show how ungodly she really is. O. Henry (William Sydney Porter) 1862-1910 • American short story writer Biographical data • B. in North Carolina, the son of a doctor. • mother died when he was three – raised by his paternal grandmother and paternal aunt, who ran a school. • Left school at 15 – trained to be a licensed pharmacist with his uncle. Young adulthood • At 20, moved to Texas for health reasons. • He worked at a sheep ranch for a while. • Moved to Austin. • Married there in 1882. • Couple had a daughter. Writing and life in Texas • 1884 started a humorous weekly The Rolling Stone. • Also started drinking heavily. • Worked as a clerk for the First National Bank. • After a few years the paper failed, so started work at the Houston Post as a reporter and columnist. Trouble and a change of life • Porter was accused of embezzling funds dating back to his employment at the First National Bank. • Leaving his wife and young daughter in Austin, Porter fled to New Orleans, then to Honduras. • After a year, he returned because of his wife's deteriorating health. She died soon afterward. • Early 1898 Porter was found guilty of the banking charges – though there is still some question of his guilt • Sentenced to five years in an Ohio prison. A new career in prison • It was in prison that he started to write short stories to support his daughter, Margaret. • Also started to use the name O. Henry to hide from his shameful past. • He spent three years in prison, and had published 12 stories while he was there. – People loved the details about Central America and what was still “the wild west” that he put into his tales. After prison • After leaving prison, he moved to New York City, where many of his later stories are set, including “The Gift of the Magi” • Some pictures of what New York looked then. like Turn of the century New York • Della and Jim’s apartment might have been in a building like these. Interpretation: The Gift of the Magi • Actually published in 1905 • Story about Christmas • It is set in New York City • One dollar and eighty-seven cents. That was all. And sixty cents of it was in pennies. Pennies saved one and two at a time we learn that this girl is young girl has got a dollar and eighty-seven cents and tomorrow will be Christmas. And that’s the dilemma. • She tried her hardest to save money; penny by penny. She cried, she’s so upset. • Which instigates the moral reflection that life is made up of sobs, sniffles, and smiles, with sniffles predominating. • a card bearing the name "Mr. James Dillingham Young. broken-down apartment building • The "Dillingham" had been flung to the breeze during a former period of prosperity when its possessor was being paid $30 per week. Now, when the income was shrunk to $20, though, they were thinking seriously of contracting to a modest and unassuming D. But whenever Mr. James Dillingham Young came home and reached his flat above he was called "Jim" and greatly hugged by Mrs. James Dillingham Young, already introduced to you as Della. Which is all very good. • Della finished her cry and attended to her cheeks with the powder rag. She stood by the window and looked out dully at a gray cat walking a gray fence in a gray backyard. she repeats the GRAY! reflects the mood she is in; also the reality the place she lived; struggling the poverty. • Something fine and rare and sterling--something just a little bit near to being worthy of the honor of being owned by Jim. • Beautiful hair; gold watch • "Will you buy my hair?" asked Della. "I buy hair," said Madame. "Take yer hat off and let's have a sight at the looks of it." Down rippled the brown cascade. "Twenty dollars," said Madame, lifting the mass with a practised hand. • Oh, and the next two hours tripped by on rosy wings. Forget the hashed metaphor. She was ransacking the stores for Jim's present. • When Della reached home her intoxication gave way a little to prudence and reason. She got out her curling irons and lighted the gas and went to work repairing the ravages made by generosity added to love. Which is always a tremendous task, dear friends--a mammoth task. • The magi, as you know, were wise men-wonderfully wise men--who brought gifts to the Babe in the manger. They invented the art of giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And here I have lamely related to you the uneventful chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. O all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.