chapter five Subject Matter: Requirements for Trademark Protection

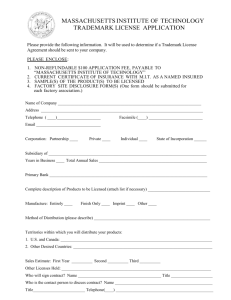

advertisement