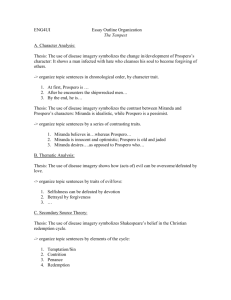

Kotarscak_Megan_September2015_Mastersdegree

advertisement