Chapter 3: Comparing Edmund's Bloodfeud laws and Wer

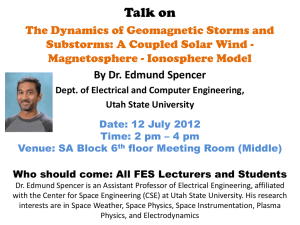

advertisement

Blood Feud or Wergild: The Practice of Pecuniary Compensation in Anglo -Saxon Society in Wer and Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws D.J.A. la Roi 3779009 Camera Obscuradreef 78 3561 XN Utrecht BA Thesis 22 June 2015 Supervisor: Marcelle Cole Second Reader: Nynke de Haas Department of Languages, Literature and Communication English Language and Culture Utrecht University 2 Inhoud Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Law Codes and Wergild ........................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2: Comparing Edmund’s Bloodfeud laws and Wer to other Anglo-Saxon Laws ......... 9 Chapter 3: Comparing Edmund’s Bloodfeud laws and Wer .................................................... 15 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 22 Appendix: Modern English Translations of Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer (anonymous) .................................................................................................................................................. 24 Works Cited.............................................................................................................................. 29 3 Introduction There are many different kinds of texts from the time of the Anglo-Saxons that were not destroyed by time. Among these are legends, charms, religious texts and laws. This paper will focus on the latter type of texts, the laws1 that some of the Anglo-Saxon kings like Alfred the Great and Edmund the Elder wrote, or had written, in order to give their people rules to live by. These laws varied in subject, however, many of the laws stipulated the economic compensation that corresponded to certain kinds of injury. Among the extant law codes there are several laws on wergild, a typically Germanic concept whereby a family could demand a pecuniary compensation for the homicide of a family member. According to Hatcher “wergild was the value set by law upon a man's life” (555). There are three Anglo-Saxon law codes that focus solely on the issue of wergild: Edmund’s second law (the Bloodfeud Laws), an anonymous text called Wer, and the Leges Henrici Primi (Charles-Edwards 22). Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer survive in three twelfth-century manuscript collections. The present paper relies on the Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 383, fos. 55r-56r, which Liebermann edited and translated into German in Die Gesetze Der Angelsachsen. Liebermann's edition also contains the Latin version of these texts, taken from the Quadripartitus, an encyclopaedia which contains all English laws in Latin translation (Wormald 199). Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws inform people what wergild has to be paid in the case of homicide, and which subsequent actions require similar compensation. Furthermore, the law code explains the importance of wise men or a counsel (wita), who advise the king (ic smeade 1 The standard edition of Anglo-Saxon laws in this study is Attenborough, F. L. The Laws of the Earliest English Kings. (Cambridge, 1922. Internet Archive. Web. 11 June 2015.) The standard edition for Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer in this study is Liebermann, Felix. Die Gesetze Der Angelsachsen. Vol. 1. (Halle A.S. :Niemeyer, 1903. Internet Archive. Web. 13 June 2015.) The Modern English translations of Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer are my own. 4 mid minra witena geðeahte, Liebermann 186, II Em. Prolog) and settle feuds (witan scylan fæhðe sectan, Liebermann 188, law 7). Last of all, Edmund’s law code explains in detail the different steps that should be undertaken when wergild has to be paid. Wer describes these different steps in more detail, adding one that Edmund’s law code left out. Furthermore, Wer adds laws on how the peace should be re-established and explains the importance of the need for pledges. Both texts explain what role family members and friends play in the division of the money and in assisting the culprit. The present study carries out a comparison of Wer and Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws to some of the other existing law codes, such as those written by Æthelberht, Alfred and Æthelstan, to see if they have many similarities or if they are completely different. The study focusses on the concept of wergild in other law codes and how it is portrayed. Edmund’s law code has not had much scholarly attention. Attenborough, for instance, completely ignores its existence in his The Laws of the Earliest English Kings, which includes law codes of most Anglo-Saxon kings. He does not mention Edmund in his introduction to the law codes of West-Saxon kings. Wer has not been included in Attenborough’s edition either, which is more logical, since the author is unknown. Wer and Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws are extremely interesting to look at, since they seem to be connected. Wer seems to be a text that was written as an addition to an already existing text. The same can be said for Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws. Both are extremely short and only address the laws surrounding wergild. At first sight, either text could have been written as a complement to the other. This study will argue that Wer was written to complement and further explain the laws in Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws. It adds certain aspects left out in Edmund’s law code and provides a clearer explanation of the process of paying wergild, something which Edmund leaves out. The present study also provides new annotated translations of Wer and of Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws (see Appendix). These two texts have both been translated once before. 5 Whitelock translated Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws in her book English Historical Documents, C. 500-1042, in 1955. Vinogradoff translated Wer in Outlines of Historical Jurisprudence, in 1920. Both these texts follow the Old English closely, with for instance Whitelock translating all the subjunctives in the text (e.g. wege, sy) with Modern English subjunctives, something that for instance Baker advices against (87). Furthermore, the new translations leave some of the typical Anglo-Saxon terms like manbot and frumgild intact in the translation, without translating them like Whitelock does, because there are no comparable terms in Modern English. Translating them with elaborate phrases that come close to the meaning would lead to an unreliable translation. Compared to both Whitelock’s translation of Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and the new translations of Edmund’s text and Wer, Vinogradoff’s translation of Wer seems old fashioned, which is logical since the translation dates from 1920. Sentences like siððan man mot mid lufe ofgan are translated with ‘thereafter the slayer may abide in love’ (314), which is not something people would use nowadays. Moreover, Vinogradoff’s Old English text has been edited in a way that it no longer resembles the original. Words like siððan and ðe are changed into sidhdhan and dhe (314). The new translations offer new insight to the phenomenon of wergild and will help readers understand Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer better. 6 Chapter 1: Law Codes and Wergild Before the Anglo-Saxons started settling in Britain around the mid fifth century, the Romans had ruled there for almost four centuries (from 43 B.C. until approximately 410 B.C.) (Baker 1). As Baker puts it: “By the beginning of the fifth century the Roman Empire was under increasing pressure from advancing barbarians, and the Roman garrisons in Britain were being depleted as troops were withdrawn to face threats closer to home” (1). When the Romans left, the cities that had been constructed along the Roman lines crumbled, as did the Roman legal system that they had introduced after conquering the native Celtic population of Britain. However, more importantly, the absence of the Romans left a whole in Britain’s defence system and the Britons, left to face hostile Picts and Scots, invited the Angles, Saxons and Jutes to their territory to help defend it (Baker 1). The laws the Anglo-Saxons brought with them would have been held in memory and no law codes existed yet. The Anglo-Saxon tradition of committing laws to paper, in the vernacular, was started by Æthelberht, the first Christian king of the Anglo-Saxons. It is not clear where he got the idea for codifying the laws, since it was not a tradition among the Anglo-Saxons. However, it is “commonly assumed or asserted that it was St. Augustine […] who taught Aethelbert how to legislate.” (Lehman 3). Augustine was sent by Pope Gregorius to spread Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England (Lehman 1), which subsequently would have brought literacy to the island. The Anglo-Saxons were not the only barbarian tribe to commit their laws to paper during this period. Like the Anglo-Saxons “others of these migrant Germans, the Burgundians and Visigoths for instance, and later the Lombards, and Franks, also wrote laws” (Lehman 2). Something in which the Anglo-Saxons differ from those other tribes, is that their law codes show “no trace of Roman law and [are], moreover, the only barbarian code[s] written in the vernacular” (2). This might seem peculiar, but Lehman has an explanation for this: “in a general way, the further the Germans were in their native state from Rome the less Roman 7 their laws looked” (2). Since the Romans were long gone by the time the Anglo-Saxons started writing down their laws, it is not strange that none of their laws resemble the Roman laws of centuries before. King Æthelberht wrote an extensive law code with as many as ninety different laws on all kinds of possible offences and customary laws. His laws were all short and “primitive of character” (Attenborough 3) and every offence is followed by the fine the offender should pay. Even the laws on marriage and children (laws 77-81) all conclude with some sort of compensation under different circumstances (e.g. Gif mon mægþ gebigeð, ceapi geceapod sy, gif hit unfacne is; ‘If a man buys a maiden, the bargain shall stand, if there is no dishonesty’ (law 77)). Æthelberht’s law code shows that “the compensation for injuries came to be treated in a perfectly business-like fashion and […] individuals and wrongs to individuals were actually paid for in carefully estimated sums of cash” (Vinogradoff 312). These offences seem to form the common denominator in all the laws that are collected in Attenborough’s book. There are on customary laws like property and divorce, laws that focus on the Church, but many, including some of the aforementioned laws, focus on crime. Kings that followed Æthelberht, like Hloðhære and Eadric, added their own laws to Æthelberht’s and extended his existing laws. Later kings, like Ine and Alfred designed new law codes that were more extensive than Æthelberht’s law code, with many ‘sub laws’ to each law. In the end, however, most of them sum up crimes and offences and conclude every law with the fine that should be paid as compensation. An example of such a law is the following law by Ine: cild binnan ðritegum nihta sie gefulwad; gif hit swa ne sie, XXX scill. gebete; ‘A child shall be baptised within 30 days. If this is not done, [the guardian] shall pay 30 shillings compensation’ (Attenborough 36-7, law 2). However, the content of royal legislation seems to have undergone some sort of transformation after the reign of Alfred (Wormals 194). Laws were no longer mainly focussed 8 on crime, but started to include more and more customary laws as well. Kings started to use the legal system as a way of ruling in a more efficient way. Wormald explains that this change happened somewhere after the rule of king Alfred: Royal charters from King Alfred's time reveal a quite remarkably high proportion of forfeitures for what can only be called (and indeed was called) 'crime': while royal legislation […] of his successors [make] clear that kings fully intended to achieve […] control of their subjects' behaviour. (194) After this, the law system became more elaborate, eventually contributing to the system that England still has nowadays. Some of the laws from Anglo-Saxon times that have not disappeared over the years focus on the notion of wergild. As mentioned before, the “wergild was the value set by law upon a man's life” (Hatcher 555). In essence this means that if a man was murdered, the murderer owed the man’s family a sum of money. The amount of the wergild was determined by a man’s place in society: Twelfhyndes mannes wer is twelf hund scyllinga. Twyhyndes mannes wer is twa hund scill’; ‘The wergild of a twelfhynde2 man is twelve hundred shillings. The wergild of a twyhynde3 man is two hundred shillings.’ (Wer, 1-2). Remarkably enough almost none of the laws speak of jail time as an alternative punishment for committing a crime. Even if the consequence of a crime was imprisonment, the sentence was always paired with a fine which had to be paid upon release. The usual wording of those laws is along the lines of the following passage from Æthelstan’s law: Gif mon ðeof on carcerne gebringe, ðæt he beo XL nihta on carcerne, 7 hine mon ðonne lyse út mid cxx scll'; 7 ga sio mægþ him on borh, ðæt he æfre geswice; ‘If a thief is put in prison, he shall remain there forty days, and then he may be released on payment of 120 shillings’ A twelfhynde man is a man “of the rank for which the wergild was twelve hundred shillings” (BosworthToller). The twelfhynde man was a þegn, and “his importance, as marked by the wergild and otherwise, was six times that of the ceorl” (Bosworth-Toller). 3 A twyhynde man is a man “of the rank for which the wergild was two hundred shillings” (Bosworth-Toller).The twyhynde man was a ceorl (Bosworth-Toller). 2 9 (Attenborough 129, law 1,3). Apparently, a prison sentence did not offer enough in the way of compensation. Chapter 2: Comparing Edmund’s Bloodfeud laws and Wer to other AngloSaxon Laws This chapter will compare certain aspects of some Anglo-Saxon law codes, such as those of Æthelberht and Alfred, to Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws, and Wer. As mentioned before, many Anglo-Saxon laws focus on different types of crimes and customary law, whereas Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer only focus on one crime, namely murder, with some ‘sub laws’ about how families and society in general should deal with a murderer. When looking at other law codes from the Anglo-Saxon times, multiple interesting elements stand out. One of the first things is that many texts mention that the fine for certain crimes is the payment of ordinary wergild, but none of these texts explain what the ordinary wergild actually is. Æthelberht, for instance, writes in one of his laws that gif cyninges ambihtsmið oþþe laadrincmannan ofslehð, meduman leodgelde forgelde; ‘if [he] slays a smith in the king's service, or a messenger' belonging to the king, he shall pay an ordinary wergeld’ (Attenborough 4, law 7). The law clearly focusses on the deed, and not on the amount of money that should be paid. Æthelberht clearly expects people to know what the ordinary wergild is. At one point he does mention how much money should be paid as wergild: Gif in cyninges tune man mannan ofslea, L scill' gebete; ‘If one man slays another, the ordinary wergeld to be paid as compensation shall be 100 shillings’ (Attenborough 7, law 5). In this passage, Æthelberht does not differentiate between men of different classes of society, which is something that the author of Wer does do, even though he does not go into much detail about this either, only mentioning the wergild of a twelfhynde man and a twyhynde man. The 10 lower classes and the classes in between the ones mentioned are not named in the text: Twelfhyndes mannes wer is twelf hund scyllinga. Twyhyndes mannes wer is twa hund scill’.; ‘The wergild of a twelfhynde man is twelve hundred shillings. The wergild of a twyhynde man is two hundred shillings’ (Wer, 1-1,1) The wergild laws written by Edmund are clearly different from Æthelberht’s law code, which focusses primarily on the compensations that should be paid for a great number of injuries and crimes. Every possible injury a man can do to another man is mentioned in Æthelberht’s law code and it goes into precise detail in stating what compensation is necessary for which crime. Some of the crimes mentioned seem somewhat insignificant today. They rank from stealing to the knocking out of teeth and knocking off the nail of the big toe (Gif þare mycclan taan nægl of weorþeð, XXX scætta to bote; ‘If the nail of the big toe is knocked off, 30 sceattas shall be paid as compensation’ (Attenborough 15, law 72).) All these offences have their own set compensation that is to be paid to the person that has been wronged. This differs from the wergild, where a man is compensated according to his rank. The different amounts of wergild are explained in Wer. A twelfhynde man, or thegn, had a wergild of twelve hundred shilling (1). The wergild of a twyhynde man, or ceorl (ordinary freeman), was two hundred schilling (1,1), a sixth of that of a thegn. This means that if a thegn was slain, the murderer owed his family twelve hundred shilling, which should be paid in different instalments. If Æthelberht’s laws mentions wergild at all, the laws do not concern a homicide, although they are usually related to this particular offence. One of the laws that mentions wergild is the following: Gif bana of lande gewiteþ, ða magas healfne leod forgelden; ‘If a homicide departs from the country, his relatives shall pay half the wergeld’ (Attenborough 7, law 23). This law seems to refer to a murder, just as in Edmund’s text, but the law does not discuss the compensation the murder itself would require, but mentions instead what should 11 be done if the murderer flees the country and cannot be found. There is one instance where Æthelberht only focusses on murder and the penalty for murder: Gif man mannan ofslea, agene scætte 7 unfacne feo gehwilce gelde; ‘If one man slays another, he shall pay the wergeld with his own money and property (i.e. livestock or other goods) which whatever its nature must be free from blemish [or damage]’ (Attenborough 9, law 30). This passage is clearly different from Edmund’s passage about the paying of wergild: Gif hwa heonanforð ænigne man ofslea, ðæt he wege sylf ða fæhþe, butan he hy mid freonda fylste binnan twelf monðum forgylde be fullan were, sy swa boren swa he sy; ‘If anyone henceforth kills any man, that he himself bears himself the feud, unless he pays them the full wergild, with the help of friends, within twelve months, whatever his birth may be’ (1). Edmund does not say that a murderer should pay the wergild with his own money. According to him, the murderer has twelve months to pay the wergild, if needed with the help of friends (1). Moreover, he does not speak of the possibility substituting the money with property. One occasion where wergild played a fundamental role was when a murder developed into a feud between families: he wege sylf ða fæhþe, butan […] forgylde be fullan were; ‘he himself bears himself the feud, unless he pays them the full wergild’(Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws, law 1). Charles-Edwards states the following: “it is important to remember that the feud could take two courses: it could either be settled by compensation, or it could be a violent vendetta” (22). Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws encouraged people to choose the first option. This way, Edmund seemingly wanted to bring down the number of vendettas, thus creating a more peaceful society. According to Charles-Edwards “he tried to do this by changing the law so that a man who refused to offer compensation could not rely on his kinsmen to rally to his defence in the ensuing vendetta” (22). This can be clearly seen in his Bloodfeud Law, were Edmund encourages family members to abandon their criminal relative (1,1). Often, however, people in Anglo-Saxon times had to be convinced of the benefits of choosing wergild over a 12 feud. Lehman explains that people living in a world where vendettas were common practice “seem commonly disposed toward revenge and often have to be pressed to offer or accept compensation” (16-7). According to the Germanic tradition “a man had a moral obligation either to kill the slayer or to exact the payment of wergild (man-price), which had to be paid to the dead man’s kin by the killer if he wished to avoid their vengeance” (Stillinger 31). Germanic tribes still had a system where family members owed the murdered man the “duty of avenging his death” (Lancaster 368), but this was now considered undesirable. The AngloSaxons had to choose, since not taking revenge or demanding wergild was considered shameful and a family would lose their honour if they did not do either of the two. The only option for them was to follow the law and choose wergild as a compensation for their loss. Edmund was certainly not the first Wessex king to write down laws. The tradition in Wessex was started by Ine, who reigned from 688 until 725 (Attenborough 34). According to Attenborough, “there is no record of any further legislation in Wessex for nearly two centuries after the promulgation of Ine's laws.” (34). King Alfred is the next Wessex king to write a lawcode, and his are interesting ones to look at. They contain elements that can also be found in Edmund’s Bloodfeud Law, which poses the question of how much Edmund’s text is inspired by Alfred’s text. In particular the following passage shows similarities with Edmund’s text: Gif hwa þara mynsterhama hwelcne for hwelcere scylde gesece, þe cyninges feorm to belimpe, oððe oðerne frione hiered þe árwyrðe sie, age he þreora nihta fierst him to gebeorganne, buton he ðingian wille. ‘If a man flees, for any manner of offence, to any monastery which is entitled to receive the king's food rent or to any other free community which is endowed, for the space of three days he shall have right of asylum, unless he is willing to come to terms [with his enemy]’ (Attenborough 65, law 2). 13 Gif hine mon on ðam fierste geyflige mid slege oððe mid bende oðe þurh wunde, bete þara æghwelc mid ryhte ðeodscipe, ge mid were ge mid wite, 7 ðam hiwum hundtwelftig scill. ciricfriðes to bote 7 næbbe his agne forfongen. ‘If, during that time, anyone injures him by a [mortal] blow, [by putting him in] fetters, or by wounding him, he shall pay compensation for each of these offences in the regular way, both with wergeld and fine, and he shall pay 120 shillings to the community as compensation for violation of the sanctuary of the Church, and he [himself] shall not have the payment due to him from the fugitive’ (Attenborough 65, law 2,1) This long passage on fleeing to a monastery when someone has murdered another, is reflected in Edmund’s text, although shortened considerably: Gif hwa cyrican gesece oððe mine burh, 7 hine man ðær sece oððe yflyge: ða þe ðæt doð, syn ðæs ylcon scyldige, ðe hit her beforan cwæð; ‘If anyone were to visit a church or my castle, and anyone there attacks or injures him: those who do that, are liable of the same, as it is stated here before’ (2). Edmund changes monastery into church, and adds his (or the king’s) own castle to the list. He does not speak of the rights the fleeing man has in such a place, and neither does he speak about the other types of places a murderer can flee to that Alfred mentions. Edmund seems to use the right of asylum as an introduction to the point he really wants to make, namely what the penalty will be for harming the murderer in the sanctuary of the church or king's castle. Edmund does not speak of the actual penalty of this offence, but mentions that it is the same amount that the murderer has to pay, which would be the wergild set for the man that is slain. He does not mention any other fines or the fact that the murderer no longer has to pay for his crime, since wrong has now been done to him as well. 14 Another remarkable thing is that Edmund’s law code is surprisingly short compared to Alfred’s law code. Edmund’s law code only contains seven different laws, with only a couple of ‘sub laws’. Alfred’s law code contains no fewer than seventy-seven laws, most of which have at least one or two ‘sub laws’; much like Æthelberht, whose law code, as mentioned in chapter 1, contains ninety laws. Edmund’s law code is definitely more concise than the two mentioned above, but not as concise as the anonymous law code Wer. Even though Wer also contains 7 laws, it has fewer ‘sub laws’ and the laws themselves are considerably shorter. Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws seem to be an extra couple of laws that were written as an addition to the already existing law codes. Since Alfred was his father and immediate predecessor, it seems logical that Edmund’s laws were an addition to Alfred’s. Alfred’s law code does not consider the specific problem of keeping feuds in check, which presumably proved a problem in Edmund’s time. Similarly, Wer adds details to Edmund’s laws that were not originally born in mind. 15 Chapter 3: Comparing Edmund’s Bloodfeud laws and Wer Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer seem to be connected, despite their differences. Edmund’s text is written from his own perspective and explains in detail why Edmund had the law code written. Wer, on the other hand, is short and to the point, without an explanation of the purpose of the text. If the texts are truly connected, it is a connection of complementation. This raises the question of whether it was Wer that was written as an addition to Edmund’s laws or if it was the other way around. Both are possible. It could be that Edmund’s text is a more elaborate version of Wer. A second possibility could be that both texts are by the same writer, but that Edmund has never been connected to the anonymous text. This study will argue that Wer was written as an addition to Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws since it covers points left unaddressed by Edmund, like the fyhtwite (Wer 6) and the explanation of to whom the healsfang falls (Wer, 5). Towards the end of this chapter some arguments will be put forward to support this claim, showing that the texts share sentence constructions and provide the same information regarding wergild. Wer adds certain aspects to Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and explains in more detail the different instalments of the wergild than Edmund does. When comparing the texts, several points clearly stand out. Whereas Edmund’s text is mostly about when wergild should be paid and about the mechanisms of a wergild case, Wer stipulates how much wergild befalls men from different classes of society and which steps the families concerned should take to properly settle a feud. Edmund’s text explains why the laws about wergild were needed: Me eleð swyðe 7 us eallum ða unrihtlican 7 mænigfealdan gefeoht, ðe betwux us sylfum syndan; ‘The unrighteous and manifold fights which exist between ourselves trouble me and all of us exceedingly’ (Prol., 2). He also explains how the 16 process of establishing of renewed peace should take place (law 7 and onwards). He includes family and friends of the murderer in his laws, stating that gif hine þonne seo mægð forlete, 7 him foregyldan nellen, ðonne wille ic, ðæt eall seo mægð sy unfah, butan ðam handdædan, gif hy him syððan ne doð mete ne munde; ‘if, after that, his relatives abandon him, and do not intend to pay for him, then I ordain that all those relatives are free from the feud, except the actual doer of the deed, if afterwards they neither give him food nor protection’ (1,1). This means that the family of a murderer shall be free of the feud if they do not help their criminal family member. Should they choose to help him out, then the feud will also fall on them. Wer also includes family members, but in an entirely different way. It does not speak of whether the feud falls onto family members in particular circumstances or not, proving that the text is just a supplement to Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws, which do explain this. However, Wer does provide information about how to secure the payment of the wergild, for which family members have to take a pledge. They shall vouch the criminal will pay and promise to oversee the payment. For the wergild of a twelfhynde man, or thegn, twelve family members are needed as pledge: eight from the paternal side of the family and four from the maternal side 7 riht is, ðæt se slaga, siððan he weres beweddod hæbbe, finde ðærto wærborh, be þam ðe ðærto gebyrige: ðæt is æt twelfhyndum were gebyriað twelf men to werborge, VIII fæderenmægðe 7 IIII medrenmægðe; ‘And it is right, that the slayer, after he has given security of the wergild, should find a pledge for the payment of the wergild, that is fitting to it; that is for the wergild of a twelfhynde man twelve men are suitable as pledge, eight on the father’s side and four on the mother’s side.’ (3) 17 One thing that Wer does not explain is how many family members are needed when it does not concern a twelfhynde man, but for instance a twyhynde man. Whereas Edmund does not mention to whom (parts of) the wergild will fall, the author of Wer speaks in detail about the different parts of wergild and who should receive which part. It meticulously explains the stages of establishing peace between a murderer and the family of his victim. First of all, the king’s peace (mund) should be established. All families involved have to lay their hands on a weapon and swear before an arbitrator, or, as the Bosworth-Toller puts it, “one who brings about agreement between parties in a dispute” (Bosworth-Toller), that they will once again have peace between them. Edmund’s laws agree on this point, only in his text it is put slightly differently. It does not mention any joining of hands on a weapon, or action from the families per se. First the slayer has to pledge to his own advocate and the advocate of the victim’s family that he intends to make amends with the family. After this, the family has to pledge that no harm will be done to the slayer, and the slayer has to pledge to pay the amount of wergild demanded for the death of his victim. Only when all this has been done can the payment of the wergild start. One common factor in both Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer is that someone else has to be present for the whole process of paying wergild and settling feuds. Wise men or counsellors (wita) play a fundamental role in the process of distributing wergild and settling feuds in Edmund’s laws. First of all, Edmund mentions the wise men who form his counsel and who advise him in the writing of his laws: ic smeade mid minra witena geðeahte; ‘I examined with the counsel of my wise men’ (II Em. Prolog). After this he starts the part of the laws in which he explains how the peace between the rivalling families shall be established by stating: “Wise men must settle feuds” (7). The wise men in this passage possibly function as judges, in the most simple way possible. They guide the advocates of both parties into accepting the wergild as compensation for the murder and they try to stop the families from 18 starting a vendetta. The author of Wer only mentions wise men once in his text. According to him, wise men decide when the wergild should be paid (Wer, 6). The only other outsider in his laws is the arbitrator who is present at the establishing of peace by joining hands on one weapon (4). His role seems similar to the role of the wise men in Edmund’s text. After all, they have the same function, namely making sure that each family follows the rules set by these two laws and end their feud. According to Wer, the wergild is divided into several parts: first the healsfang (‘grasp of the neck’ (Charles-Edwards 22)) should be paid, which falls to the children, brothers and paternal uncles (Wer 5). Charles-Edwards states that “it seems to be a payment designed to prevent those who would naturally feel most hatred for the slayer from starting a vendetta” (22). After the healsfang, the manbot, the fyhtwite and the frumgild should be paid (Wer 6). Wer does not specify to whom these three parts of the wergild fall, suggesting that this might differ for each case or that it was common knowledge. According to the Bosworth-Toller, the manbot is the “fine to be paid to the lord of a man slain” (Bosworth-Toller). The fyhtwite is a “fine for fighting” (Bosworth-Toller). Lastly, frumgild is translated as a first payment or compensation,—the first payment or instalment of the price [wer] at which every man was valued, according to his degree, to be paid to the kindred, or guild-brethren, of a slain person, as compensation for his murder (Bosworth-Toller). This is remarkable, because the author of Wer clearly speaks of paying the healsfang first, an amount of money paid to the kindred. This raises the question of whether the frumgild was payable to family members who were not among the people receiving the healsfang, or the nuclear family (Charles-Edwards 24), or if this translation is not the only one possible. Further research did not lead to another possible translation of frumgild, so the first option of interpreting frumgild to mean people outside the nuclear family seems the most likely, more 19 so because the translation also states that guild-brethren instead of kindred are the ones who can receive the healsfang. They could be people from the same society or even from the same guild. Paying the wergild to someone outside the family was a practice which was more and more common after the tenth century, the time in which Edmund lived (Lancaster 375). Moreover, even if the frumgild had to be paid to next of kin, the text does “not show at what point kinship, for the purpose of wergeld payments, came to an end” (Charles-Edwards 25). This suggests there was a way of knowing this in Anglo-Saxon times, which would make it unnecessary to explain this further in the laws. Interestingly, the author of Wer continues the passage of the distributing of the wergild with the line: “and so forth, so that it is fully paid in the time ordained by the wise man.” (Wer 6). This suggests that there are other parts of the wergild to be divided up and paid. The author, however, chooses not to go into detail about this. It suggests that the manner in which the wergild was divided and to whom which parts fell was common knowledge in those times. The text also explains that there is a set time in which the different parts should be paid. Between every instalment, there should not be more than 21 nights (or days), something that Edmund’s text agrees on. Edmund leaves out one thing in his summing up of the instalments of wergild: the fyhtwite. The fact that the other three instalments are mentioned in both texts, but that the fyhtwite was left out, can be proof of the fact that Wer was written as a supplement to Edmund’s law code. Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer both contain similar wording, with one sentence that is identical and others that are very similar. This shows that the two texts are connected. There is one sentence that occurs in both texts: Ðonne ðæt gedon sy, ðonne rære man cyninges munde; ‘When that is done, then let them establish the king’s peace’ (law 7,2 in Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws, law 4 in Wer). The entire sentence occurs in the same structure, 20 with every word and case ending identical, something which is remarkable, because spelling could vary greatly in Anglo-Saxon times, as is seen with for instance nihtan in Wer and nihton in Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws. The next sentence that occurs in both texts is the following: of ðam dæge on XXI nihton gylde man healsfang; ‘within 21 nights from that day the healsfang is to be paid’ (law 7,3 in Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws). Wer has a slightly different version of this sentence, with added information: of ðam dæge on XXI nihtan gylde man CXX scll’ to healsfange æt twelfhyndum were; ‘within 21 nights from that day shall he pay 120 shilling as healsfang from the twelfhynde wergild’ (law 4,1 in Wer). The first thing that is different is the lack of a case ending with niht in Edmund’s text. This is not extremely remarkable, since case endings were already starting to disappear from the language. The author of Wer seems to have changed niht into nihtan since this is also used in the rest of the sentences with this construction (although Edmund uses nihton instead of nihtan, which is a different form of the same case ending). The second element that stands out is the addition of CXX scll’ to […] æt twelfhyndum were; ‘120 shilling as healsfang from the twelfhynde wergild’. Edmund does not explain how the amount of money that is the healsfang is to be determined, something which the author of Wer adds to his list of instalments of the wergild. This was seemingly too unclear in Edmund’s text. The last pair of sentences that are similar are the following: ðæs on XXI niht manbote; ðæs on XXI niht ðæs weres ðæt frumgyld; ‘21 nights from that the manbot; 21 nights from that the frumgild’ (law 7,3 in Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws) and of ðam dæge […] on XXI nihtan gylde man ða manbote; ðæs on XXI nihtan ðæt fyhtewite; ðæs on XXI nihtan ðæs weres ðæt frumgyld; ‘within 21 nights from [that], the manbot should be paid; within 21 nights of that the fyhtwite; within 21 nights of that the frumgyld of that wergild’ (law 6 in Wer). As pointed out before, the author of Wer adds the element of the fyhtewite. It seems it was a necessary 21 addition to Edmund’s text, because it is an important instalment of the wergild, and should not be forgotten. All these different elements stand as proof that Wer was indeed written as a supplement to Edmund’s Law code. 22 Conclusion The Germanic tribes that settled in Britain knew their own traditions and laws, which they brought with them. The Romans had already left Britain and not much of their legal system remained. King Æthelberht was the first Anglo-Saxon king to start writing down laws, possibly influenced by St. Augustine. He used the vernacular for this, something unseen among other Germanic peoples (Lehman 2). The first laws mainly focussed on crimes and their subsequent compensation to the person wronged. Each law ended with a certain sum of money which should be paid by the perpetrator. Most of the kings wrote their own version of already existing laws, adding minor changes to them and extending existing laws. After the reign of Alfred, however, the legal system started to be used as a ways of governing a king’s subjects (Wormhald 194). Some of the laws focussed solely on the notion of wergild, which was the amount of money a man or woman was worth. This amount differed per class. Germanic tribes still had a tradition of avenging a beloved one’s death, either by starting a feud or by demanding wergild to be paid. King Edmund was one of the first kings to formulate laws for the process of demanding and paying wergild, in his Bloodfeud Laws. He differs in this with Æthelberht and Alfred. They both wrote about wergild, but not in the way Edmund did. Æthelberht and Alfred do not explain what the wergild of different men is, which another text on wergild, Wer, does. Æthelberht and Alfred also fail to provide information on how the wergild should be paid, something which Edmund and the author of Wer do extensively. Edmund does seem to use parts of one of Alfred’s laws, which discuss what should happen to a murderer when he flees to a monastery (Attenborough 65). This could prove that Edmund’s law code in itself is an addition to Alfred’s law code. Edmund’s Bloodfeud laws and Wer also differ greatly from the other texts when it concerns length. They both only have seven laws, where for instance 23 Alfred’s law code consists of seventy-seven different laws, which again suggests that both texts are written as additions to others. When comparing Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer with each other, a couple of remarkable elements stand out. First of all, Wer seems to be a text written as an addition to another text. This text is most likely Edmund’s law, since they share elements and even (parts of) sentences. The authors both write exclusively about wergild: how and to whom it should be paid, how much should be paid, and in what manner it should be paid. Both texts include family as part of the process of establishing renewed peace, however, they also include outsiders. In both texts, wise men, or counsellors (wita), play an important role, more so in Edmund’s text than in Wer. Wer also mentions the need of an arbitrator to overlook the process of establishing peace. Both the wise men and the arbitrator seem to function as judges, helping the families and making sure that everything goes according to the law. Lastly, both texts make assumptions as to the knowledge the people had of wergild and how it should be paid. Not everything is explained in the laws, and the text Wer, for instance, uses terms like “and so forth” (6) when it comes to the different instalments of paying wergild, assuming that the people knew how to continue the payments. The occurrence of sentences that are in part or entirely similar in both Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer indicate that the texts are connected. At first instance, either text could be written as complement to the other, however, after examining both, it is clear that Wer is an addition to Edmund’s law code. Wer shares a couple of sentences with Edmund’s text, but adds certain elements to it, like the fyhtwite and the explanation of to whom the healsfang falls. It fills in gaps left uncovered by Edmund and helps make the laws more understandable. The two laws together create a text that explains the concept of wergild perfectly and inform all people in Anglo-Saxon society when and how they should deal with it in an attempt to halt the vendetta. 24 Appendix: Modern English Translations of Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws and Wer (anonymous) Edmund’s Bloodfeud Laws B H [II Em. Eadmund cyning cyð eallum King Edmund makes known to all Prolog] folce, ge yldrum ge gingrum, ðe on people, both nobles and servants, who his anwealde synd, ðæt ic smeade are in his jurisdiction, that I examined mid minra witena geðeahte, ge with the counsel of my wise men, both hadedra ge læwedra, ærest, hu ic clerical and lay, first, in what way I mæhte Cristendomes mæst aræran. could most raise Christianity. [Prol., Ðonne ðuhte us ærest mæst 1] ðearf, ðæt we ure gesibsumnesse 7 geðwærnesse fæstlicost us betweonan heoldan gynd ealne minne anwald. First, then, it seemed to us most necessary that we keep our peacefulness and mildness firmly between us beyond all my jurisdiction. [Prol., Me eleð swyðe 7 us eallum ða 2] unrihtlican 7 mænigfealdan gefeoht, ðe betwux us sylfum syndan; þonne cwæde we: The unrighteous and manifold fights which exist between ourselves trouble me and all of us exceedingly; therefore we proclaimed: [1] [1,1] Gif hwa heonanforð ænigne man ofslea, ðæt he wege sylf ða fæhþe, butan he hy mid freonda fylste binnan twelf monðum forgylde be fullan were, sy swa boren swa he sy. Gif hine þonne seo mægð forlete, 7 him foregyldan nellen, ðonne wille ic, ðæt eall seo mægð sy unfah, butan ðam handdædan, If anyone henceforth kills any man, he himself bears the feud, unless he pays them the full wergild, with the help of friends, within twelve months, whatever his2 birth may be. 1 If, after that, his3 relatives4 abandon him, and do not intend to pay for him, then I ordain that all those relatives are free from the feud, except the actual ðæt has been omitted, because, even though it explains what is decreed (i.e. ‘we proclaimed that he himself bear the feud’), it makes the ME text unclear. 2 ‘his’ in this case refers to the man slain. 3 seo means ‘the, that, those’, but in this construction, ‘his’ seemed more suitable. 4 Most translators use ‘kindred’ a translation of mægð. This seems old-fashioned. The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary calls this term ‘old-fashioned or formal’(Bosworth-Toller). The choice between following for instance Attenborough, whose translations are almost a hundred years old or trying to find a more modern translation and translating mægð with ‘relatives’ was difficult, but in the ended I opted for the last option. I am aware the verbs in the Old English are singular, but I had to translate these with a plural because I chose ‘relatives’ as translation. 1 25 gif hy him syððan ne doð mete ne munde. doer of the deed, if afterwards they neither give him food nor protection. [1, 2] Gif ðonne syððan hwilc his maga hine feormige, ðonne beo he scyldig ealles ðæs ðe he age wið þone cyning 7 wege ða fæhðe wið þa mægðe, forðam hi hine forsocan ær. If then afterwards any of his relatives harbour him, then he is liable to forfeit all5 that which he possesses to the king and to bear the feud against the relatives, because they abandoned him earlier. [1, 3] Gif þonne of ðære oðre mægðe hwa wrace dó on ænigum oðrum men butan on ðam rihthanddædan, sy he gefah wið þone cyning 7 wið ealle his frind 7 ðolige ealles ðæs he age. If then anyone from the other family were to take revenge on any other man except on the actual perpetrator of the crime, he shall be at feud with the king and with all his6 friends and he is to lose all that he possesses. [2] Gif hwa cyrican gesece oððe mine burh, 7 hine man ðær sece oððe yflyge: ða þe ðæt doð, syn ðæs ylcon scyldige, ðe hit her beforan cwæð. If anyone were to visit a church or my castle, and anyone there attacks or injures him: those who do that, are liable of the same, as it is stated here before. [3] 7 ic nelle, þæt ænig fyhtewite oððe manbot forgifen sy. And I do not wish, that any fyhtewite7 or manbot8 shall be forgiven. [4] Eac ic cyðe, þæt ic nelle socne habban to minum hirede, ær he hæbbe godcunde bote underfangen 7 wið þa mægðer gebet on bote befangen 7 to ælcum rihte gebogen, swa biscop him tæce, ðe hit on his scyre sy. Also I make known that I do not wish to have a visiting at my court, before he has received religious assistance and undertaken the prescribed compensation9 to the family, and has submitted to every law, as the bishop in whose parish it is instructs him. [5] Eac ic ðancige Gode 7 eow eallum, ðe me wel fylston, 7 þæs friðes, ðe we nu habbað æt ðam þyfðam; ðonne gelyfe ic to eow, þæt ge willan fylstan to ðissum swa miccle bet, swa us is eallum mare ðærf, ðæt hit gehealden sy. Also I thank God and you all, who helped me well, 10for the peace that we now have from thefts; then I trust to you, that you wish to protect this so much better, as the need is greater for all of us, that it is kept. ealles is genitive case, but could not be translated as such due to the translation of scyldig. I choose to add ‘to forfeit’ to the translation because it is something that seemed necessary to make this part understandable. 6 Presumably the king’s friends. 7 The fyhtwite is a fine paid for fighting (Bosworth-Toller). I chose to leave in the actual term, because there is no literal translation of the word. 8 The manbot is a fine paid to the lord of a man slain (Bosworth-Toller). I chose to leave in the actual term, because there is no literal translation of the word. 9 I follow Whitelock here. 10 Omitted ‘7’ 5 26 [6] Eac we cwædon be mundbrice 7 be hamsocnum: se ðe hit ofer ðis dó, ðæt he þolige ealles ðæs he age, 7 si on cyninges dome, hwæðer he lif age. Also we proclaimed concerning the violation of the mundbrice11 and concerning the hamsocn12: that anyone who commits it after this, is to lose everything that he possesses, and it is by the choice of the king, whether he keeps13 his life. [7] Witan scylan fæhðe sectan: ærest æfter folcrihte slaga sceal his forspecan on hand syllan, 7 se forspeca magum, þæt se slaga wylle betan wið mægðe. Wise men must settle feuds: first, after common law, the slayer must give a pledge to his advocate, and the advocate to the relatives, that the slayer wishes to make amends with the relatives. [7, 1] Ðonne syððan gebyreð, þæt man sylle ðæs slagan forspecan on hand, ðæt se slaga mote mid griðe nyr 7 sylf wæres weddian. Then afterwards it is fitting, that one shall give a pledge to the slayer’s advocate, that the slayer may approach under safe-conduct14 and pledge himself. [7,2] Ðonne he ðæs beweddad hæbbe, ðonne finde he ðærto wærborh. When he has pledged this, then he is to find security for the payment of wergild next. [7, 3] Ðonne ðæt gedon sy, ðonne rære man cyninges munde; of ðam dæge on XXI nihton15 gylde man healsfang; ðæs on XXI niht16 manbote; ðæs on XXI niht ðæs weres ðæt frumgyld. When that has been done, then let them establish the king’s peace; within 21 nights17 from that day the healsfang is to be paid; 21 nights from that the manbot18; 21 nights from that the frumgild19. ‘king’s peace’. Mundbryce, from mund-bryce. Mund = protection/peace, bryce = violation. This translation is given by the Bosworth-Toller, under mund IV. 12 ‘attack on a man’s house’. Hamsocnum, from ham-socn. Ham = home, socn = attack (Bosworth-Toller) 13 ‘owns’ 14 I follow Whitelock here, who gives: “that the slayer may approach under safe-conduct” (429) 15 Nihton = nihtum. In the 9th and 10th century in Wessex, the case endings –on and –an could be used instead of –um. (Baker, xcii). 16 Remarkable is that in his edition of manuscript B, Libermann added ‘-on’ to ‘niht’. However, he did not do this in manuscript H (Liebermann, 190). 17 Both nihton and niht are singular, but the number in front of it (XXI) requires a plural translation. 18 “The fine paid to the lord of a man slain” (Bosworth-Toller). 19 “The first instalment of the price [wer] at which every man was valued, according to his degree, to be paid to the kindred of a slain person, as compensation for his murder” (Bosworth-Toller). 11 27 Wer H [1] Twelfhyndes mannes wer is twelf hund scyllinga. [1, 1] Twyhyndes mannes wer is twa hund scill’. The wergild of a twyhynde 21 man is two hundred shillings. [2] Gif man ofslægen weorðe, gylde hine man swa he geboren sy. [3] 7 riht is, ðæt se slaga, siððan he weres beweddod hæbbe, finde ðærto wærborh, be þam ðe ðærto gebyrige: ðæt is æt twelfhyndum were gebyriað twelf men to werborge, VIII fæderenmægðe 7 IIII medrenmægðe. If a man is killed, one should pay for him according to his birth. And it is right, that the slayer, after he has given security of the wergild, should find a pledge for the payment of the wergild that is fitting to it; that is, for the wergild of a twelfhynde man twelve men are suitable as pledge, eight on the father’s side and four on the mother’s side. [4] When that is done, then let them establish the king’s peace, that is that they all, from each family, by joined hands on one weapon before an arbitrator, give a pledge, that the king’s peace shall stand. Within 21 nights22 from that day shall he pay 120 shilling as healsfang from the twelfhynde wergild. Ðonne þæt gedon sy, ðonne rære man cyninges munde, ðæt is ðæt hy ealle gemænum handum of ægðere mægðe on anum wæpne ðam semende syllan, ðæt cyninges mund stande. [4, 1] Of ðam dæge on XXI nihtan gylde man CXX scll’ to healsfange æt twelfhyndum were. 20 B The wergild of a twelfhynde20 man is twelve hundred shillings. [5] Heaslfang gebyreð bearnum, broðrum 7 fæderan; ne gebyreð nanum mæge ðæt feoð bute ðam ðe sy binnan cneowe. The healsfang falls to the children, brothers and paternal uncles23; none24 of that money falls to relatives but those that are within the joint25. [6] Of ðam dæge, ðe ðæt healsfang agolden sy, on XXI nihtan gylde man ða manbote; ðæs on XXI nihtan ðæt fyhtewite; ðæs on XXI Within 21 nights from the day when the healsfang is paid, the manbot26 should be paid; within 21 nights of that the fyhtwite27; within 21 nights of that þegn (Bosworth-Toller) ceorl (Bosworth-Toller) 22 Nightan = nightum. In the 9th and 10th century in Wessex, the case endings –on and –an could be used instead of –um (Baker, xcii) 23 This is not a dative plural, but it makes sense to translate the word with a plural, to conform with the rest of the sencence. 24 This sentence includes a double negative: ne and nanum. This is not reflected in the translation. 25 Close relatives. 26 “The fine paid to the lord of a man slain” (Bosworth-Toller). 27 “The fine for fighting” (Bosworth-Toller). 21 28 nihtan ðæs weres ðæt frumgyld; 7 swa forð, þæt fulgolden sy on ðam fyrste, ðe witan geræden. the frumgyld28 of that wergild; and so forth, so that it is fully paid in the time ordained by the wise man. [6, 1] Siððan man mot mid lufe ofgan, gif man hwile fulle freondrædne habban. Afterwards the slayer29 may acquire love, if he wishes to have full friendship. [7] Eal man sceal æt cyrliscum were be þære mæðe don, ðe him to gebyreð, swa we be twelfhyndum tealdan. The same thing shall be observed with the wergild of a ceorl, according to the sum that befits him30, the same way as we have discussed about a twelfhynde man. “The first instalment of the price [wer] at which every man was valued, according to his degree, to be paid to the kindred of a slain person, as compensation for his murder” (Bosworth-Toller). 29 I translated man with ‘the slayer’, because it makes the text clearer. 30 I follow Vinogradoff here, who gives: “The same thing shall be observed touching the wergild of a ceorl, according to the sum that befits him” (314). 28 29 Works Cited Attenborough, F. L. The Laws of the Earliest English Kings. Cambridge, 1922. Internet Archive. Web. 11 June 2015. Baker, Peter S. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2000. Google Books. Web. 15 June 2015. "'' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary." '' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Grant Agency of Charles University. Web. 14 June 2015 Charles-Edwards, T. M. "Kinship, Status and the Origins of the Hide." Past & Present No. 56 (1972): 3-33. JSTOR. Web. 10 June 2015. "'fiht-wíte' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary." 'fiht-wíte' - Bosworth–Toller AngloSaxon Dictionary. Web. 14 June 2015. "'frum-gild' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary." 'frum-gild' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Web. 14 June 2015. Hyams, Paul. "Feud and the State in Late Anglo-Saxon England." Journal of British Studies 40.1 (2001): 1-43. JSTOR. Web. 4 June 2015. Lancaster, Lorraine. "Kinship in Anglo-Saxon Society: II." The British Journal of Sociology 9.4 (1958): 359-77. JSTOR. Web. 13 June 2015. Lehman, Warren Winfred. "The First English Law." The Journal of Legal History 6.1 (1985): 1-32. Google Scholar. Web. 12 June 2015. Liebermann, Felix. Die Gesetze Der Angelsachsen. Vol. 1.: Halle A.S. :Niemeyer, 1903. Internet Archive. Web. 13 June 2015. Little, A. G. "Gesiths And Thegns." Eng Hist Rev The English Historical Review IV.XVI (1889): 723-29. JSTOR. Web. 04 June 2015. "Kindred Noun - Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com." Kindred Noun - Definition, 30 Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com. Web. 14 June 2015. "'mann-bót' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary." 'mann-bót' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Web. 14 June 2015. "'sémend' - Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary." 'sémend' - Bosworth–Toller AngloSaxon Dictionary. Web. 14 June 2015. Stillinger, Jack, Deidre Lynch, Stephen Greenblatt, and M. H. Abrams. "Beowulf." Preface. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. 1. New York, NY: W.W. Norton &, 2006. 29-33. Print. Vinogradoff, Paul. Outlines of Historical Jurisprudence. London: Oxford UP, 1920. Google Books. Web. 15 June 2015. Whitelock, Dorothy. English Historical Documents, C. 500-1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955. Google Books. Web. 15 June 2015. Wormald, Patrick. "Anglo-Saxon Law and Scots Law." The Scottish Historical Review 88.2 (2009): 192-206. JSTOR. Web. 4 June 2015.