Cardiac Arrest made easy

advertisement

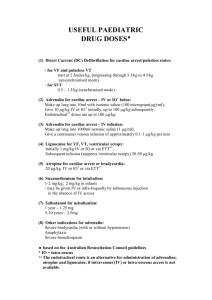

Cardiac arrest resuscitation made easy Tony Smith Medical Director, St John Intensive Care Medicine Specialist, Auckland City Hospital Cardiac arrest resuscitation • Talking about cardiac arrest in the accident and medical clinic setting, not in the emergency department setting – – – – – – – – – General overview of out of hospital cardiac arrest Guidelines The evolving emphasis on chest compressions Airway Drugs Defibrillation Decision making with regard to starting and stopping Cases for discussion Questions Take home messages • Continually emphasise doing the basic things well – Good BCLS saves more lives than ACLS does • Chest compressions are the most important part of CPR for most patients • Focus on keeping things simple Out of hospital cardiac arrest: overview • 3 cardiac arrests in NZ per day (resuscitation attempted) – One per 4000 people per year • 80% are primary – Obvious cardiac cause or no obvious cause • 20% are secondary – Due to another obvious non-cardiac cause (drowning, trauma, hanging, poisoning) • For primary cardiac arrest – – – – Median age is 65 70% male 80% occur in the home 50% receive bystander CPR Out of hospital cardiac arrest: overview • Initial rhythm in primary cardiac arrest – – – – 50% VF 30% Asystole 18% PEA 2% VT • Overall 20% reach hospital and 8% survive • Outcomes are very rhythm dependent Rhythm VT VF PEA Asystole % Reach Hospital 80% 40% 10% 5% % Survival 70% 20% 1% 1% Out of hospital cardiac arrest: overview • Paediatric cardiac arrest – – – – – A completely different disease to adult cardiac arrest 5% of out of hospital cardiac arrest 90% secondary and 70% asystole 15% reach hospital and 1% survive ROSC with BCLS is a marker of survival • Secondary cardiac arrest – – – – – A completely different disease to primary cardiac arrest 20% of out of hospital cardiac arrest 60% asystole and 30% PEA 10% reach hospital and 1% survive Cardiac arrest in presence of personnel, immediately reversible cause, quick ROSC (within a few minutes) is a marker of survival Guidelines • There are lots – – – – NZRC, ARC, AHA, ERC, ILCOR…. They are all subtly different… These differences often cause confusion But the differences are not important • Which guideline you follow is not important – Keeping it simple is… • We (St John Clinical Management Group) have made a decision not to align with any one guideline – We have chosen to do some things differently where there is no evidence and we can simplify things – For example: ratios, joules and drug doses Emphasis on chest compressions • Chest compressions are the most important part of CPR – CCR rather than CPR (flow is more important than content) – Particularly in primary cardiac arrest – Particularly early in cardiac arrest (the first 4-6 minutes) • Ratio has changed from 15:2 to 30:2 for non-intubated – No evidence for either ratio – The principle is more important than the exact ratio • Focus on the chest compressions – – – – Minimise pauses, continuous whenever possible Rate of approx 100/min Adequate depth Frequent change of person doing the compressions (every two minutes) The airway • The LMA has a rapidly evolving role for airway management, including cardiac arrest – You do not need a cuffed ETT – The LMA has a high success rate in inexperienced hands (and ETT a low success rate) • I would recommend removing ETTs from clinics and replacing them with LMAs • Ventilation rates are important and often overlooked – 8-10 breaths a minute – Higher rates cause blood flow to fall during CPR Drugs • No evidence that drugs improve survival from cardiac arrest – High dose adrenaline is no better than normal dose – Amiodarone improves ROSC rates in recurrent VF • My view: keep it simple – Don’t use atropine, calcium, bicarbonate, vasopressin, magnesium – The benefit of using amiodarone is very small and probably isn’t worthwhile in a clinic where cardiac arrest is rare – Give 1 mg (adults) adrenaline every four minutes – Use a decent flush (the easiest is a running line) – Keep paediatric dosing simple Paediatric dosing • There is no evidence for current paediatric doses of drugs in cardiac arrest – They are hard to remember – They are hard to calculate in a rush • The St John approach – All children 50kg and above get adult doses – All other children are rounded off to the nearest of 10, 20, 30 or 40kg and dosed accordingly • Take the adult dose, draw it up to a total of 5ml and give 1ml for every 10kg – Works for all emergency drugs, including cardiac arrest – Dose differs a little from guidelines, but this doesn't matter and it simplifies dosing and reduces error Defibrillation • All moving away from stacked shocks to single shocks – Reduces pauses in chest compressions – Still role for initial stacked shocks if cardiac arrest occurs in presence of defibrillator • All recommend immediate CPR after defibrillation (without rhythm or pulse check) • Different recommendations on joules (150-360J) – Between guidelines – Between manufacturers – Between monophasic and biphasic • There may be a role for CPR before defibrillation in some – Particularly if in VF for more than a few minutes – Right heart dilation an impediment to defibrillation • Confused? Defibrillation • We (St John CMG) recommend a simple approach – Start with one round of stacked shocks if cardiac arrest occurs in presence of defibrillator, then go to single shocks – Always use maximum joules – Opt for defibrillation first – Round kids off to nearest 10kg and use 5J/kg Defibrillation • Manual defibrillators are $15,000-$20,000 • AEDs are $3000-$5000 • In clinics I would recommend an AED rather than a manual defibrillator – All clinical staff should know how to use it Starting and stopping • These decisions can be difficult • A resuscitation attempt should begin in most patients – Except where the patient is clearly dead (livedo, rigor mortis) – Or where they are clearly dying and it would be inappropriate – A competent patient can decline therapy but neither a patient nor their family can demand therapy that is medically inappropriate • Some scenarios have >99% mortality rates – Unwitnessed cardiac arrest with initial rhythm of asystole Starting and stopping • The chances of survival fall rapidly with time – Exponential falling curve • There is no absolute cut off when mortality becomes zero • Resuscitation attempts requiring longer than 20 minutes of CPR have a very high mortality rate – We recommend stopping at around 20 minutes unless there is a clinical reason to continue for longer • Transport to hospital with CPR enroute usually has no role Cases for discussion • Cases • Invite audience participation • Reinforce the take home messages Case #1 • A 40 year old man is delivered by car to your clinic – He was found collapsed by his family in the toilet • He is in cardiac arrest • You begin a resuscitation attempt and a defibrillator is attached – He is in asystole… • What are you going to do? Case #1 – my thoughts • Check the leads and check the gain – It could be fine VF • Make sure it isn’t bradycardia – Which can look like asystole at a quick glance • Concentrate on good chest compressions • This is unwitnessed cardiac arrest with asystole – – – – Predicted mortality is > 99.9% The tiny number who survive have a high chance of severe disability I would not continue for very long (around 5 minutes) if truly asystolic I would then declare him dead Case #2 • A 70 year old man attends your clinic with chest pain – Soon after arrival he has a cardiac arrest – VF • What are you going to do? Case #2 – my thoughts • This is about as good as it gets – Precordial thump unless you can shock in next five seconds – Start with stacked shocks, then go to single shocks (followed by immediate CPR without rhythm check) – Focus on good chest compressions (uninterrupted if possible), that is: CCR rather than CPR – Place an LMA (keep ventilation 8-10/min) – Drugs not an initial high priority • I would continue with a vigorous resuscitation attempt – I would be prepared to continue for twenty to thirty minutes Case #3 • Imagine case #2 again • This time however, the patient has a medic alert on his wrist which you notice for the first time as you are attaching the defibrillator • It says “not for resuscitation in the event of cardiac arrest”… • What would you do? Case #3 – my thoughts • This is a very difficult situation – It is very hard not to shock VF – You could pretend you haven’t seen the bracelet… • However, this man has made a clear advanced directive – A competent patient has the right to decline treatment – A patient is competent unless proven otherwise • I would stop resuscitation attempts – I wouldn’t shock him • If others insisted on a resuscitation attempt I would politely decline to be involved Case #4 • A 42 year old woman attends your clinic with asthma – She has a long history of asthma, with severe attacks requiring hospitalisation • Despite continuous nebulised salbutamol she rapidly gets worse over about ten minutes with severe respiratory distress, she is unable to talk and is becoming increasingly confused… – Why is she becoming confused? • What do you do? Case #4 • She develops a falling level of consciousness and becomes rapidly comatose with agonal gasps and ineffective breathing • The rhythm on the monitor is sinus tachycardia at a rate of 140/min, but the rate is rapidly slowing… • What do you do? Case #4 – my thoughts • This has a high mortality rate if handled badly and a low mortality rate if handled well – She isn’t in cardiac arrest yet, but could be soon • I would prioritise – Avoiding dynamic hyperinflation, use a very low ventilation rate of around 6/min (focusing on oxygenation rather than ventilation) – Treating her asthma aggressively (adrenaline a high priority) – Chest compressions not initially high on my list • Tension pneumothorax is rare in this setting – Signs are predominantly in the circulation – Drainage technique important if you think it is present • If she goes on to become asystolic the mortality rate becomes 99% Summary: take home messages • Individual guidelines are not important – Keeping it simple is • The chest compressions are the most important part of CPR – CCR rather than CPR • The LMA can replace the ETT in most cardiac arrests • Adrenaline is the only drug you need to remember – Paediatric dosing can be made easy • Defibrillation – – – – Defibrillation first Max joules, stacked followed by single shocks Immediate chest compressions without rhythm check AEDs have many advantages over manual defibrillators St John Clinical Procedures • Developed by the St John CMG • Issued to St John clinical staff • Very popular with medical and nursing staff • $15 a copy • Tony.Smith@stjohn.org.nz St John Clinical Procedures St John Clinical Procedures Thank you • Tony.Smith@stjohn.org.nz