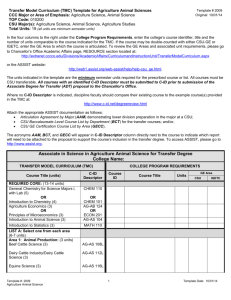

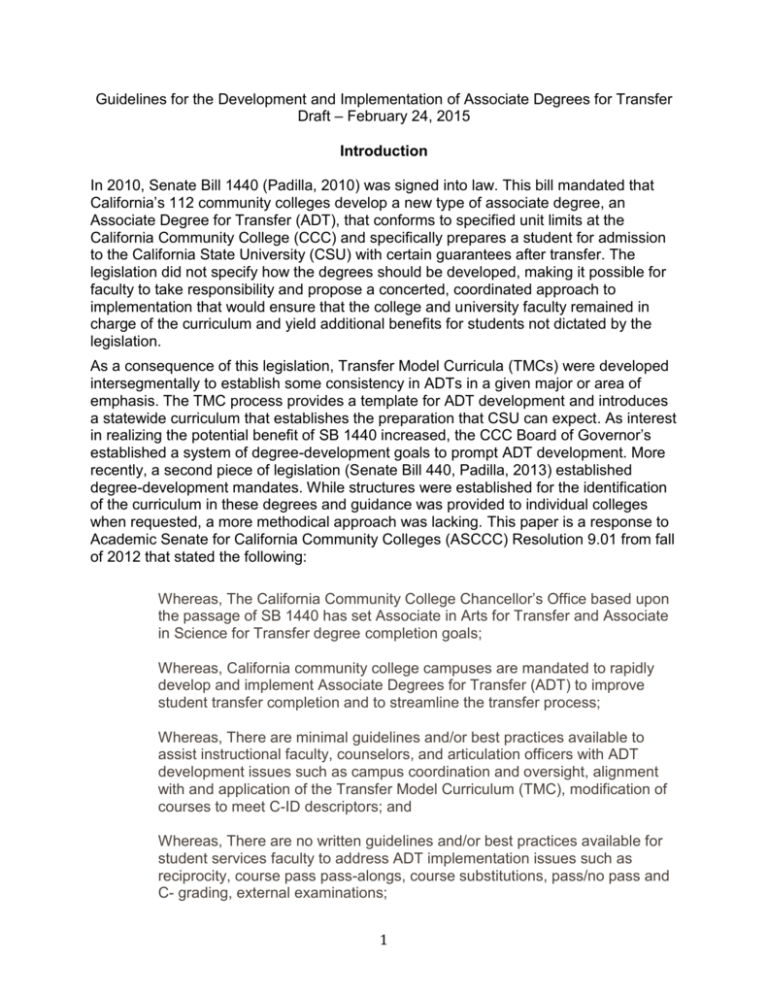

IV. C. 2. ADT

advertisement