Olsson Axel -...or Essay - Lund University Publications

advertisement

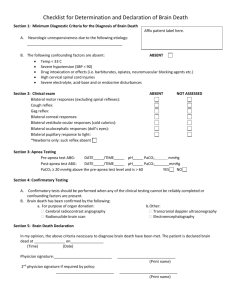

Department of Economics Lund University Preferential trade agreements and bilateral trade flow in Latin America A study performed using the gravity model of trade Bachelor Essay, Autumn 2013 Author: Axel Olsson Mentor: Zouheir El-Sahli Summary After studying economic integration it doesn’t come as a shock that preferential trade agreements (PTA) have an effect on the countries within the PTA, or outside the PTA for that matter also. The majority of the Latin American countries have been considered as developing countries for the better part of the 21st century, and have, for the most part, been secluded from the world market. Since the introduction of in particular ALADI (Asociación Latinoamericana de Integración, 1980), but also Mercosur (Mercado Común del Sur, 1991), the Latin American trade market has completely changed. The point of ALADI was to create a stable socio-economic environment for the involved countries, as well as ensuring development in a manner that eventually succumbed to a common Latin American market. Mercosur was created a decade later, where the major countries within ALADI had the goal to integrate further, by creating their own common market, where they benefited more towards each other without the remaining ALADI countries. To measure the exact effects that these PTAs have had on the different countries, an econometric estimation must be performed. The regression that will be executed here is the well-known gravity model of trade. A total of 22 countries are included in the equation, which means that there are 462 country-pairs that are examined over the time period of 1975-1995. The study shows that there is a specific correlation between the entry of a preferential trade agreement and the bilateral trade flow, especially concerning Mercosur. Looking at the first estimation, it is evident that the membership of Mercosur has led to an increase in bilateral trade flow with a rather substantial margin. Since there is a problem of multicollinearity in the estimations, this has led to it being hard to analyse ALADI in the specific estimations. However, when looking at the statistics, the evidence shows that countries that have entered a PTA (both ALADI and Mercosur) have increased their bilateral trade flow. This has to do with several factors that will be presented throughout the essay. Key Words: Latin America, Gravity Equation, Bilateral Trade Flow, Preferential Trade Agreement, ALADI and Mercosur 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….5 2. Background………………………………………………………………………..6 2.1. ALADI…………………………………………………………………….6 2.2. Mercosur………………………………………………………………..6-7 2.3. Purpose of PTAs………………………………………………………..7-8 3. Previous Studies………………………………………………………………..8-10 4.The Gravity Equation…………………………………………………………10-11 5. Method……………………………………………………………………………11 6. Econometric equation……………………………………………………………11 6.1. Variables……………………………………………………………..11-12 6.2. External Countries………………………………………………………12 6.3. Logarithms…………………………………………………………...12-13 6.4. Time Interval…………………………………………………………….13 7. Fixed effect……………………………………………………………………….13 8. Data……………………………………………………………………………….14 8.1. Sources………………………………………………………………….14 8.2. Panel Data…………………………………………………………..14-15 9. Regression terminology…………………………………………………………15 9.1. Autocorrelation…………………………………………………………15 9.2. Heteroscedasticity……………………………………………………15-16 9.3. Null hypothesis…………………………………………………………..16 9.4. T-value……………………………………………………………….16-17 9.5. Multicollinearity…………………………………………………………17 9.6. Endogeneity…………………………………………………………..17-18 9.7. Zero Trade Flows………………………………………………………18 10. Equation Estimates…………………………………………………………….19 10.1. Fixed country specific and fixed period effects……………………..19-20 10.2. Fixed period effects……………………………………………………21 10.3. White test for heteroscedasticity……………………………………….21 11. Figures………………………………………………………………………..22-25 12. Analysis………………………………………………………………………26-27 13. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...28-29 3 14. Equation Estimate Figures……………………………………………………30 14.1. Fixed country specific and fixed period effects………………………30 14.2. Fixed period effects…………………………………………………..31 14.3. White test for heteroscedasticity……………………………………..32 15. References……………………………………………………………………..33 15.1. Websites…………………………………………………………….33-34 15.2. Authors/Studies……………………………………………………..34-35 16. Appendix……………………………………………………………………….36 16.1. Included Countries…………………………………………………....36 16.2. Included Variables……………………………………………………37 4 1. Introduction Preferential trade agreements have long been an important and influential part of regional integration. Ever since the formation of the earliest preferential trade agreements it has been obvious that PTAs have had a large impact on both the members and the non-member parts of the PTA. Over the past decades PTAs (mainly regional) have become immensely popular. Seeing to the beneficial possibilities that PTAs can provide this is in no way a surprise. PTAs can vary a lot regarding the geographical size, with them being as large as a continent to being an agreement between two small countries. PTAs are not something solely associated with prominent developed countries, as a matter of fact rather the opposite. Developing countries often negotiate an agreement with a more developed country, e.g. Costa Rica is involved in a PTA with Canada (URL 10). This then helps the less developed country to gain comparative advantages towards similar under-developed countries. Frequently asked questions revolving preferential trade agreements are such as: what kinds of measurements are used to actually measure exact effects? Are PTAs always beneficial? What effects do they have on the member countries towards their bilateral trade flow? These questions are just a few that are to be answered in this essay. The goal of the essay will be, with the help of the gravity model of trade, to determine the impact that a formation of a preferential trade agreement has on (both member and non-member) countries’ bilateral trade flow. The focus field will be Latin America, in particular the formation of the initial free trade agreement of ALADI (Asociación Latinoamericana de Integración) in 1980 and also the more recent and niched formation of MERCOSUR (1991) (see section 16.1 for full country list). There have been several similar studies regarding these questions, where the most notable study regarding the Latin American countries is the one by Carillo & Li (2002, Trade Blocks and the Gravity Model: Evidence from Latin American Countries). Earlier theories and equations on this particular area will be brought up later on in the essay. 5 2. Background 2.1 ALADI ALADI was formed in 1980 with the goal to integrate the Latin American countries so that an eventual common Latin American market could be established. The main reason for the formation of ALADI is to promote and in some ways also regulate the reciprocal trade and eventually be able to reach a common market (URL 1). Large parts of the ALADI region are suffering from major poverty, with the poverty scale varying quite a bit even domestically within the countries. Looking at one of the main countries, Brazil, with just over 200 million inhabitants, where not only the class-difference, but also the living standards vary immensely. The so-called Favelas in Brazil are a prime example of this. Even though the domestic law enforcements are trying to clear out the Favelas, the largest Favela, located in the centre of Rio de Janiero, still has around 1 million inhabitants. The standards in the Favelas are almost unimaginable. To have a finished roof over ones head is considered to be a form of luxury in the Favelas (URL 2). Naturally the other ALADI countries also have large variations between the rich and the poor, but Brazil’s situation is probably the most prominent. ALADI consists of 13 countries and operates from the Uruguayan capital Montevideo. For the ALADI countries a main part of when the integration was formed was to be able to include the country of Panama. The Panama Canal is central to basically half a world’s shipping industry, with ships and fraters travelling through the canal on a daily basis all year round. By including Panama, the remaining countries were able to benefit from this advantage and gain a stronger bargaining position when negotiating with countries outside of ALADI (GATT, 1982). Five of the members of ALADI have since then formed an even more niched free trade agreement known as the Mercosur. 2.2 Mercosur Mercosur was formed in 1991 and consists of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela. Bolivia has since 2012 been considered as an acceding member (URL 8), but since the time period for this essay is between 1975-1995, that will not be taken into consideration. Quite like ALADI, Mercosur also has the purpose of enhancing and promoting free trade, but amongst others, the main 6 differences are that Mercosur is a full customs union and more integrated than ALADI. A customs union is characterized by the countries having a common external tariff, meaning that all the goods entering the countries must have the same import quotas and preferences (URL 12). Another main objective with Mercosur is to become an international “big shot” in the trading market. With around 300 million inhabitants in the Customs Union, the member-countries of Mercosur have gained a stronger negotiation position on the world trade market (URL 9). By having a lot of natural resources, partly thanks to the enormous Amazon rain forest, regional non-members obtain a form of dependency of the Mercosur members, which leads to Mercosur gaining large advantages in the world-trade market compared to the time before the formation of Mercosur. Furthermore, this means that because it was the larger countries from ALADI that formed Mercosur, they had more bargaining power towards the outside world than the smaller ALADI-members countries, e.g. Peru, which in its turn made it even more difficult for the non-Mercosur members. Why is it these exact countries are part of the Mercosur? When analysing the question, the answer will prove to be rather straightforward. Compared to the nonMercosur members, the members already had a large negotiating-power within Latin America, and were in some ways the unspoken leaders within the region. Worth noting in the analysis is also that the amount of inhabitants in the member countries are largely superior to the non-members, which in its turn also leads to a stronger market negotiation position. 2.3 Purpose of PTAs The Mercosur members had, as when ALADI was formed, several reasons to integrate further. One of the main, if not the main, reason was the possibility to introduce free trade regarding produced goods, factors and services for the countries involved. When enhancing their integration, the Mercosur countries decided to fixate an external tariff, as well as adopt a trade policy, which was unanimous for the member countries. This policy was both directed towards the countries that weren’t a part of Mercosur, so that the actual members of Mercosur could receive greater benefits, but also to ensure increased trade within Mercosur. A major role of Mercosur was to ensure that the member countries were able to achieve free competition within the PTA. By coordinating important policies, regarding things like 7 foreign trade, the monetary system, customs, transports etc. this could be achieved. Another main objective was the ability to be able to freely move manpower between the different states (URL 11). The Asunción treaty regarding Mercosur wisely decided to take a few small steps before targeting the free movement of manpower. By firstly targeting free-trade zones and a unification for customs, the member states were able to negotiate forward a common market, which in it’s turn led to the ability to freely move manpower between the member states. Because of the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) principle, any advantage that a Mercosur member may be able to achieve they must extend this advantage towards the other members of the PTA (Persson, 2013). 3. Previous studies One of the most notable previous studies is the work of Bergstrand & Baier (2006), where they discuss the effect on the bilateral trade flow when entering the EEC (European Economic Community) and the CACM (Central American Common Market) during a time period of 40 years. Bergstrand and Baier, just like is intended in this essay, used the gravity model of trade to find out the impact a PTA has on the bilateral trade flow. Bergstrand and Baier discuss the matter of CACM being noticed as “the most advanced and successful regional integration scheme of Latin America in the 1960s.” (Bergstrand & Baier, 2006). However the success of CACM was not to be continuously successful when the 1970s came. A war between the member countries of El Salvador and Honduras led to Honduras withdrawing from the PTA and the eventual downfall (even though it took almost 30 years) of CACM. When Bergstrand & Baier regarded the EEC, the results were opposite. After many hurdles the EEC has eventually evolved into the European Union, which has to be seen as a largely successful PTA as a whole. A rather obvious conclusion that can be drawn from Bergstrand & Baiers study is that there is no simple answer to whether an PTA automatically benefits the bilateral trade flow of the involved countries; it generally depends from PTA to PTA and around other, sometimes external, circumstances than just trade, e.g. the war in the CACM case. Another previous study is one provided by Celine Carrère (2004). The purpose of Carrères study is to apply the gravity model to ex-post regional trade agreements. In 8 other words Carrère applies the gravity model to actual results rather than predictions of the regional trade agreements. Carrère emphasizes that she is applying the gravity model with “proper specification”, meaning that Carrère is able to acknowledge the effects on both trade creation and trade diversion, as well as being able to include the unobservable characteristics and also take into account some of the explanatory variables endogeneity (see section 9.6.). The data collected by Carrère is from over 130 countries and Carrère used panel data (see 8.2.) when performing the equation. One main difference from Bergstrand and Baiers study is that Carrère draws the conclusion that compared to earlier studies, regional integration has shown to increase trade in a significant way between country-pairs, however this often leads to the entire world-trade decreasing as a consequence. A third previous study is the one that probably is the most relevant towards this essay, which is the one mentioned in the introduction. Carlos Carillo and Carmen A Li performed the study in 2002. Similar to this essay Carillo and Li also used the gravity model to estimate their equations. The main goal of Carillo’s and Li’s study is to research about the effects that the Andean Community and Mercosur had on both intra-regional and intra-industrial trade from 1980-1997 (2002, Carillo & Li). Unlike this essay, there are no external countries that are included, i.e. only members of either Andean Community and/or the Mercosur are part of the equation. A general consequence of the lack of the external countries can lead to less variation in the equation results. However, in Carillo and Li’s study their goal is only to find out internal matters, such as trade and industrialization, therefore this doesn’t matter in their study. The authors divided up the timeline into two parts (1980-1989 & 19901997) as well as dividing up the goods into three different main categories; Homogenous, reference price and differentiated. These main categories were later split into four different sub-categories (agricultural intensive, mineral intensive, labour intensive and capital intensive). After their estimation, it was proved that the Andean Community had a significant effect on, in particular the capital-intensive goods, both concerning the differentiated and the reference price products. As for the Mercosur, those agreements only had a positive effect on the reference price products, specifically the capital-intensive category. When comparing this study towards this essay, this essay will not be divided into two different timelines and the study will especially not be divided up into different categories like Carillo and Li’s is. Instead this essay will be analysed 9 depending on how the variables in the gravity equation are affected by the different PTAs. 4. The Gravity Equation The Gravity Equation can be used within several different fields, in this essay the focus will be on the gravity model of trade. The outline of the gravity model of trade is the prediction of bilateral trade flows. Some tools used to analyse the bilateral trade flows are the size of the country in mind, economically speaking, and also the distance between, in this case the economic centres of the country-pairs in matter. A main area where the gravity model of trade is used is to see how effective a trade agreement actually is (Carrère, 2004), which makes this model very suitable for this essay. The gravity model is built upon several different variables linked to the different country-pairs. Some of the variables, such as if the countries share a border, speak the same language and the bilateral distance between the countries are not affected by time in any way. Other variables used in the gravity model, such as GDP per capita, bilateral trade flow and if the countries are part of a PTA are timedependent. The bilateral trade flow represents the amount of trade between the country-pairs and is represented by lnTFijt in the actual equation. The gravity equation first originated in 1962 and was developed by the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen. Before Tinbergen had presented the gravity equation, it was believed by the better part of the economic world that the Hecksher-Ohlin model was enough when describing the world’s trade. The gravity model of trade has therefore been revolutionizing when describing the worlds trade, since it is much more sufficient then the Hecksher-Ohlin model and takes more contributing factors into consideration (Frankel, 1998). Another economic-pair that in a way revolutionized the model was Anderson and van Wincoop, who in 2003 used a system of equations that was non-linear, so that the endogenous (see 9.6.) change from the trade liberalization price terms could be taken into consideration (Anderson & van Wincoop, 2003). The study will start by comparing a country pair (e.g. Argentina & Belize) throughout a specific period of time, in this case 1975-1995, and then replicate this process until the data concerning all 462 country-pairs has been calculated. When estimating the gravity equation the regression that will be used is Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). The OLS-method minimizes the sum of squares for the predicted 10 responses of linear calculation with the observed responses from the data (Dougherty, p.85). Fixed country specific and fixed period effects will replace the dummy variables when processing the actual estimation (see section 9 & 10). 5. Method The gravity equation is a so-called multiple regression model. The main characteristic that makes the gravity equation able to be represented by the multiple regression models is the fact that it has several explanatory variables (Dougherty, p.151-153). The multiple regression models equation is as following: yi = β1 + β2x2i + β3x3i + ... + βKxKi + ei In the equation, yi represents the dependent variable, β represents the intercept of the explanatory variables that in their turn are x2i + x3i +...+ xKi . 6. Econometric equation As earlier mentioned the essay will analyse the effect PTAs have on bilateral trade flow by using the gravity equation with all its different variables. In this essay the gravity equation is represented by the following regression: lnTFijt = β0 + β1 ln(GDP per capita)it + β2 ln(GDP per capita)jt + β3 DISTij + β4 ADJij + β5 LANGij + β6 ALADIijt + β7 MERC ijt + εijt 6.1. Variables lnTFijt represents the bilateral trade flow between country i & j for a specific year, lnTFijt and is also the dependent variable. ln(GDP per capita)it and ln(GDP per capita)jt represent the GDP per capita for a specific country for a certain year. i & j stand for the different countries (e.g. Argentina & Belize). The variables DISTij, ADJij and LANGij are not correlated with time in any way. This means that the value will be constant for the entire time period for these variables. DIST represents the bilateral distance between the economic centres of the country-pairs, ADJ represents if the country-pair share a geographical border or not and lastly LANG explains 11 whether the country pair have the same official language as one another. The variables ADJ and LANG are binominal, meaning that either the number 1 or 0 represents them. If the number is 1 between the country-pair this means that they in fact share a border (or a language depending on the variable). The final two variables, ALADIijt and MERCijt show if the country pair is part of the same preferential trade agreement. These two variables are also binominal, also being represented by the number 1 or 0. εijt is considered as the error term in this equation. All of the variables mentioned, except the dependent lnTFijt variable, are therefor explanatory (see Appendix 16.2.). 6.2. External Countries When performing the equation, it is important not only to take in account the countries that actually are a part of either of these preferential trade agreements, but to also include regional non-members. This is partly to get a lot of variation and to compare members to non-members. Furthermore, the benchmark is non-members and the effects of the PTAs are then estimated in comparison to members. Why it is important to choose specifically regional countries is that because of geographical location, countries tend to trade more with nearby countries. The countries outside of ALADI and Mercosur that have been taken into account are: Belize, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Nicaragua and Suriname. The goal was of course to try and include all of the Latin American countries in the equation, but unfortunately there wasn’t enough data concerning Haiti and Puerto Rico which means that the results will not be exactly correct, but as good as. 6.3. Logarithms Since the dependent variable in the gravity equation is using the logarithm of the trade flow values this can cause problems. The main problem is that country-pairs that have zero trade flow values cannot be defined, since the logarithm of zero is indefinable. Earlier studies have had this problem as well and the easiest way to avoid this obstacle is to assume the value 1 on the country-pairs that have zero trade flow, since the logarithm of 1 is always defined as zero. This is considered to be much more efficient than neglecting the values all together (Martin & Pham, 2008). 12 6.4. Time Interval The essay has, as earlier mentioned, analysed the time interval between 1975-1995. This exact time period was chosen because by using these years it can clearly be distinguished how the different preferential trade agreements have affected the concerned countries, since ALADI was formed in 1980 and Mercosur in 1991. Another factor was also the matter of CACM (Bergstrand & Baier, 2006) being existent on a large scale before the years in this essays interval. To be certain that the existence of CACM didn’t interfere with the results, it was best to focus on the interval of 1975-1995. 7. Fixed Effect When performing an equation that is of the gravity equations calibre, the model can allow the parameters to change for both individuals (in our case countries) and for the time period. A way to deal with this is by adding a fixed effect. The fixed effect treats the observed quantities as if they were non-random, regarding the explanatory variables. This ensures that the coefficient of slope will stay constant throughout the regression, depending on if one chooses to use it on time or countries, which is the coefficient of slope that will remain constant. It is important to distinguish the difference between a random and fixed effect. Compared to the random effect the fixed effect is a cause of non-random quantities, whereas the random effect is, by definition, a consequence of random causes. The fixed effect replaces the dummy variable, leading to the use of only the variation within the countries. The lack of using fixed effect means that one must include the variation between the countries, as well as the variation within the countries (Dougherty, p. 525). When fixed effects are applied, an important part is to ensure that every parameter that may be correlated with the regression gets time independent effects added. The fixed effects that are included in the estimations in this essay are both country specific as well as period fixed effects. 8. Data 13 8.1. Sources The goal was to be able to determine, with as much accuracy as possible, how the bilateral trade flow is affected by the formation of the respective preferential trade agreements. To be able to go through with this it was very important to have a sufficient amount of data. Therefor, it was important to have a large amount of country pairs, since there weren’t really that many variables (both dependent and explanatory). The total amount of country pairs came to a total of 462, with there being 22 countries in total (see section 16.1 for more information). The data used in the gravity equation comes mainly from two different sources. These are the World DataBank and the website www.cepii.fr (URL 7), where the latter is an acknowledged website which has specified in, amongst other things, the gravity equation. Cepii allowed us to find the data concerning the dependent variable (bilateral trade flow) in the equation. The GDP per capita for the individual countries was easily accessible from the World DataBank’s website (URL 6). The GDP per capita for the various countries are all measured in US dollars. The bilateral distance between the different countries’ economic centres was also accessible on www.cepii.fr (by using the “geodist” tool) and is measured in kilometres. The rest of the data is very easy to find with a quick search on the Internet, since it has come to be very public information. To see if the country-pairs are adjacent, what their official languages are and to see if they are part of either ALADI and/or Mercosur, this information was accessible from Wikipedia. Since the information is acknowledged and well known, it is considered sufficient to use Wikipedia as a source. When deciding if there should be data for every year or only take data for every five years within the interval, the decision was rather easy. Since the trade can vary quite a lot from year to year and the goal is to get as accurate an answer as possible, the best decision was to use data from every year. 8.2. Panel Data The gravity equation is built, as earlier mentioned, on one dependent variable and a couple of explanatory variables. Before performing the actual regression, with the help of Eviews, the data had to be sorted. In this case, the choice was to use panel data, partly because it was the kind that was best suitable for the process of the gravity equation, but also because it was rather simple to sort and perform in Excel. What is meant by the last sentence is that panel data can be both balanced and unbalanced. 14 When the panel data is unbalanced, it means that there necessarily doesn’t have to be data for every specific country for every year (Dougherty, p. 515). Since there are a few years where this occurs for different countries, e.g. Argentina during the Falkland war in 1982-1983, the choice of panel data became even more beneficial. When panel data is balanced it points towards all countries showing data for every single specific year. 9. Regression terminology 9.1. Autocorrelation When observations are dependent on one another this shows that there is a serial correlation between the disturbance terms. If this assumption is fulfilled then the regression is known to have autocorrelation, or in other words, the covariance is something else than zero. Autocorrelation has come to be apparent most often when performing a regression analysis with time-series data. In the case of this essay, it is more than likely that there is autocorrelation since we have chronological time-series data. When autocorrelation is apparent the OLS-estimate doesn’t have the lowest variance amongst all the expected value estimates. The most common version of autocorrelation is positive autocorrelation, where the characteristics of positive autocorrelation can be seen when analysing the Durbin-Watson (DW) statistic (Dougherty 2011, p. 429-430). If the DW-value is any number below two, there is considered to be autocorrelation. 9.2. Heteroscedasticity When the random variables have different variances for all the observations this indicates that heteroscedasticity is existent for the random variable, and naturally when the random variables have the same variances, homoscedasticity is existent. Similar to autocorrelation, the consequences of heteroscedasticity mean that the OLSestimate doesn’t have the lowest variance amongst all of the expected value estimates. The point of defining if there is either hetero- or homoscedasticity is to see how efficient the chosen estimates are (Dougherty 2011, p. 283). If heteroscedasticity is apparent this means that the variance concerning the regression coefficient is larger, which in its turn leads to worse estimates than if the regression indicated homoscedasticity. Heteroscedasticity can also be the cause of the standard errors 15 showing wrongful results, which means that the F- and T-tests will have results that are easily interpreted wrongfully. To see if heteroscedasticity is apparent the most common way to detect heteroscedasticity is to perform the White test (White, 1980). 9.3. Null hypothesis The null hypothesis (often written as: H0) represents, in a statistical model filled with data, the fact whether there is a correlation between the two (or more) measured parameters (Dougherty, p. 37). The point of the null hypothesis is to determine whether the experiment in matter is false or not. When deciding whether or not to reject the null hypothesis or not, the following algebra is good to start from: Reject H0 if | t | > t α/2, n-2 Don’t reject H0 if | t | < tα/2, n-2 Which in other words means the following; α assumes the variable for the significance level, where the significance level represents the probability that the null hypothesis may actually be correct. If a lower significance level had been selected, then that would obviously mean that the probability of the null hypothesis being correct would be larger than previously. In this essay the significance level of 10%, 5% and 1% will be assumed. The purpose of choosing these levels is to minimize the risk of type II errors, which means that the null hypothesis isn’t rejected even though it is correct (Dougherty, p.42). Type I errors are characterized by the opposite of type II, meaning that the null hypothesis is rejected even though it is correct (Dougherty, p. 38). 9.4. T-value When a regression has been executed, T-values will appear, where they play the part of deciding whether or not the null hypothesis is to be rejected (Westerlund, p. 116). Looking at the algebra in the previous paragraph; tα/2, n-2, this represents the critical value, with the sub-variables, (α/2 & n-2) representing the fact that a twotailed hypothesis test is being performed and n represents the amount of observations (in this case 9701). By using degrees of freedom as well as the significance level, it is possible to interpret the critical value, which will be presented later on in the results section. 16 9.5. Multicollinearity When the equation one is trying to estimate has more than one explanatory variable, there is always a risk for multicollinearity. This phenomenon occurs when two or more of the explanatory variables are dependent on one another (Westerlund, 2005). When there is perfect multicollinearity, the estimation will be impossible to perform in the computer software program (in this case Eviews) leading to that at least one of the variables must be eliminated. After the elimination of the variable(s) there may still be multicollinearity and the problem with this is that it is hard to see which of the variables in matter is the one affecting the Y-term (in this case lnTFijt). Perfect multicollinearity is apparent in the first estimation that is performed (see section 10.1.) and the solution that has been used to deal with it is also presented in the same section. 9.6. Endogeneity When there is correlation between the variable and the error term in a model, in our case the gravity model, it is said to be endogenous. There are four different types of ways that endogeneity can come to surface; measurement error, simultaneity, omitted variables or autoregression (where the errors are auto correlated). What distinguishes an endogenous variable from an exogenous variable is that an endogenous variable has values that are determined from interactions within the model, whereas an exogenous variable is determined from external interactions (Dougherty, p. 332). When performing econometric equations, problems with endogeneity often occur. When defining problems with endogeneity it is important to revise the four abovementioned ways as to how endogeneity can arise. First of all we must define what the different areas actually mean (Wooldridge, 2013). A measurement error is defined as the difference between a quantity’s true value and the measured value of the quantity (Dougherty, p.85) To find out if there is a measurement error in the essay, the DurbinWu-Hausman test is the best way to test if there in fact is a measurement error. When a model neglects at least one important factor from the equation this is referred to as omitted-variables bias. When the assumed specification in a regression analysis is incorrect, the bias that shows from the estimates is the omitted-variables bias (Dougherty, p. 252). A random process that often describes different time varying 17 processes within e.g. economics is often referred to as an autoregressive model. When a dependent variable is determined together with an explanatory variable simultaneity occurs. Usually an equilibrium mechanism is used to perform this (Dougherty, p. 335). Typically, when a problem occurs with endogeneity, the cause of this is because the error term in the regression model is correlated with the dependent variable, instead of the explanatory variable. (Sørensen, 2012). For every independent regression in matter, the problem of endogeneity is unique. Initially there was a large problem with endogeneity in this essay, where the GDP-data was measured in actual GDP without considering the geographical and demographical size of the countries. This made the estimation results to be rather obscure and unrealistic. However, when the GDP-data was changed to GDP per capita that specific endogeneity problem disappeared. 9.7. Zero Trade Flows The dependent variable that is part of the performed equation in this essay is based on how much different country-pairs trade with each other. Since there are 22 different countries, for several obvious reasons some country-pairs will not trade every year between 1975-1995. Some critics may say that a large reason as to why the trade flow is zero is because of the lack of reporting the trade between different country-pairs, but generally the trade between the countries really is non-existent. This leads to the trade flow between various country-pairs assuming the value zero. With slightly over 40% of the country-pairs (all 21 years included) obtaining the value zero, therefore not trading with one another, this clearly has an affect on the results (Martin & Pham, 2008). If the zero values of the trade flow are excluded, heteroscedasticity can create large biases in different samples (Hurd, 1979). Therefore it is very important to include the zero trade flows when compiling ones data in the gravity mode, since this will neglect the problems that are created when excluding zero trade flows (Arabmazar & Schmidt, 1981). 10. Equation Estimate Results In this section of the essay the results from the econometric equations will be presented. As earlier mentioned (see section 4.), the method that has been used whilst performing the different equations is Ordinary Least Squares. When executing the equation in Eviews, it was important to choose various different settings so that the 18 most accurate results could be calculated and compared with one another. The different versions of the calculations will be presented separately in this section. For all of the estimations a significance level of 10%, 5% and 1% will be assumed, meaning that with the probability of 90%, 95% and 99% that the correct value will be identified within the confidence interval (Dougherty, p. 40). Since the amount of observations is exactly the same for all the different equations (as well as the significance level), this means that the critical value will be the same for each and every one of the equations. Since the test is two-tailed, this means that the top column in the table (Dougherty, p. 533) is the one to use. Because the amount of observations is superior to 600, that means that the “infinity level” in the t-table must be identified and used in the equations. For example when the significance level is 5%, the critical value of all the equations will be 1.96. 10.1. Fixed country specific effects and fixed period effects (for stats see 14.1.) The first equation is characterized by having fixed country specific effects as well as fixed period effects. When looking at the Durbin-Watson statistic, it is noticeable that it is way below the value of two (see section 8.1.) and rather close to zero, meaning that there is apparent autocorrelation. When considering the variables in the equation, it is noticeable that there are a few variables missing (see section 14.1.). The reason for the lack of variables is because of multicollinearity. When performing the estimation with all of the variables the equation suffered from perfect multicollinearity, which is acknowledged as a socalled dummy variable trap. The reason for the dummy variable trap occurring is that when using fixed effects alongside panel data (which is used in this study), dummies are created leading to an overflow of dummies. The solution to this is to remove one or two dummy variables in order for the equation to be performed (Dougherty p. 235236). In 14.1 the variables LANG and ADJ had to be removed for the possibility to perform the equation, which unfortunately led to somewhat deceptive results. The most important part is however that the variables concerning the preferential trade agreements are included in the results, which they are. When analysing the results the first thing that is noticeable is that only two variables are significant, no matter what significance level works as guidelines. These two variables are ln(GDP per capita)it and the variable concerning Mercosur 19 (MERC), meaning that they are separated from zero. When applying these results practically, it is important to see what kind of effect these variables have on the bilateral trade flow (lnTFijt). If ln(GDP per capita)it increases by one percentage this will lead to the bilateral trade flow increasing with the coefficient of ln(GDP per capita)it, in this case 20.22333. Looking at the MERC variable the conclusion that can be drawn is that for the countries that are members of Mercosur their difference will be a positive of 371728 (coefficient) concerning the bilateral trade flow compared to not being a member. Regarding the other preferential trade agreement variable ALADI, it is hard to say anything about it, because of the presence of multicollinearity, the variables value must be assumed as 0 and more advanced conclusions than that would be unwise to draw. Since this regression is built on time-series data, the possibility of spurious regression is large and it is important to try and avoid it. Looking at R2 and its value (0.600697), the conclusion is that the value isn’t nearly high enough to be concerned about spurious regression. In short, spurious regression means that two variables that do not have any correlation, appear to have correlation, which can often be caused by a third so-called unseen factor (Dougherty, p. 475). 20 10.2. Fixed period effects (for stats see 14.2.) Another estimation that was also to be performed was testing with only fixed period effects and neglecting the country (fixed and random) effects. The purpose of this was to get some diversification in the results and see if there could be any large difference compared to when there was fixed effects for both countries and period. Another reason was also that the possibility of multicollinearity decreases a lot when not including fixed country-specific effects, which allows us to exclude less variables. Regarding the results the variables ln(GDP per capita)it, ADJ, LANG, ALADI and MERC are all significant at all the three testing-levels (10%, 5%, 1%), and the DIST variable is significant when testing for all the levels except at 1%. The conclusion of this is that when ln(GDP per capita)it increases by a percentage, the bilateral trade flow will increase with its coefficient (16.51978). The members of ALADI and Mercosur will have a difference (compared to prior-membership) of their coefficients (45619.93 respectively 467151.5). The same goes for ADJ and LANG, if the country-pair in matter (e.g. Argentina and Paraguay) in fact share a border or the same language the bilateral trade flow difference will be their respective coefficients (98434.58 & -24548.95). 10.3 White test for heteroscedasticity (for stats see 14.3.) The purpose of this regression is mainly to test if there is heteroscedasticity. When calculating the existence or not of heteroscedasticity, the degrees of freedom must be identified. This is done in the following way: the amount of regressors in the equation minus one. In this case the amount of regressors is 8, so the degrees of freedom is 7. The next step is to read from the chi-squared statistic table, which in this case shows (at a 5% significance level) a result of 14.067. To see if there is apparent heteroscedasticity, the test statistic must be calculated. By multiplying R2 (0.243968) with the amount of observations (9701 minus 2), the test statistic is 2366,73357. Since the test statistic is so much larger than the chi-squared statistic, this means that there is a lot of heteroscedasticity (Dougherty, p. 286). This means that the null hypothesis for heteroscedasticity is rejected. . 21 11. Figures Figure 1.1. 250000 Bilateral trade flow 1975 & 1985 for Colombia(US $) 200000 150000 100000 1975 50000 Colombia & Argentina Colombia & Belize Colombia & Bolivia Colombia & Brazil Colombia & Chile Colombia & Costa Rica Colombia & Cuba Colombia &… Colombia & Ecuador Colombia & El Salvador Colombia & Guatemala Colombia & Guyana Colombia & Honduras Colombia & Mexico Colombia & Nicaragua Colombia & Panama Colombia & Paraguay Colombia & Peru Colombia & Suriname Colombia & Uruguay Colombia & Venezuela 0 1985 Figure 1.1 shows the bilateral trade flow between Colombia and the rest of the included countries for the years 1975 (blue line) and 1985 (red line). These exact years were chosen since they are five years either side of the formation of ALADI, which makes it easy to see the impact of the preferential trade agreement. It is immediately evident that Colombia’s bilateral trade flow has increased immensely towards all of the members of ALADI and the bilateral trade flow is rather unchanged towards the non-members. This shows that the introduction of ALADI definitely has had a positive impact on the trade between Colombia and the remaining members of ALADI. 22 Figure 1.2. Bilateral trade flow 1975 & 1985 for Guatemala(US $) 1975 Guatemala & Argentina Guatemala & Belize Guatemala & Bolivia Guatemala & Brazil Guatemala & Chile Guatemala & Colombia Guatemala & Costa Rica Guatemala & Cuba Guatemala &… Guatemala & Ecuador Guatemala & El Salvador Guatemala & Guyana Guatemala & Honduras Guatemala & Mexico Guatemala & Nicaragua Guatemala & Panama Guatemala & Paraguay Guatemala & Peru Guatemala & Suriname Guatemala & Uruguay Guatemala & Venezuela 90000 80000 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 1985 Figure 1.2 shows the bilateral trade flow between Guatemala and the rest of the countries included in the equation. The years are the same as in figure 1.1 and the colour of the lines represent the same years. The reason that Guatemala was chosen in this figure is to see how a non-member of the preferential trade agreement ALADIs bilateral trade flow was affected by the introduction of ALADI. Guatemala’s bilateral trade flow hasn’t increased with any of the country-pairs, as a matter of fact rather the opposite. It is most noticeable on the countries that joined ALADI, but also on e.g. El Salvador and to some extent Honduras (that aren’t a part), that the bilateral trade flow has decreased rather drastically. 23 Figure 1.3. Bilateral trade flow 1986 & 1995 for Argentina (US $) 4500000 4000000 3500000 3000000 2500000 2000000 1500000 1986 1000000 1995 0 Argentina & Belize Argentina & Bolivia Argentina & Brazil Argentina & Chile Argentina &… Argentina & Costa… Argentina & Cuba Argentina &… Argentina & Ecuador Argentina & El… Argentina &… Argentina & Guyana Argentina &… Argentina & Mexico Argentina &… Argentina & Panama Argentina &… Argentina & Peru Argentina &… Argentina & Uruguay Argentina &… 500000 Figure 1.3 shows the difference of the bilateral trade flow between Argentina and the rest of the countries included in the equation. The blue line represents five years before Argentina entered Mercosur and the red line represents four years after Argentina had entered the Mercosur. The first noticeable thing is obviously that the bilateral trade flow has increased immensely between Argentina and Brazil (both Mercosur members) during this decade. The other two country-pairs that have very noticeable differences are Argentina & Mexico, also Argentina and Uruguay (both Mercosur members). Overall, from this chart, it is evident that (at least for Argentina) the bilateral trade flow has increased with its fellow members of Mercosur since the formation of the PTA (even a slight increase between Argentina and Paraguay). This chart then shows that, just as the estimations showed, if there is a correlation between the entry of a PTA and bilateral trade flow, the trade can increase (and in Argentina’s case has) between the fellow PTA members. The purpose of choosing Argentina when showing this chart was partly because Argentina is a member of Mercosur, but also the fact that Argentina is geographically placed very well when looking at the Mercosur members, sharing a border with all of the countries (except Venezuela) and also speaking the same language as all of the involved countries, excluding Brazil that is. 24 Figure 1.4. 6000000 Bilateral Trade Flow 1986 & 1995 for Brazil (US $) 5000000 4000000 3000000 2000000 1986 0 1995 Brazil & Argentina Brazil & Belize Brazil & Bolivia Brazil & Chile Brazil & Colombia Brazil & Costa Rica Brazil & Cuba Brazil & Dominican Republic Brazil & Ecuador Brazil & El Salvador Brazil & Guatemala Brazil & Guyana Brazil & Honduras Brazil & Mexico Brazil & Nicaragua Brazil & Panama Brazil & Paraguay Brazil & Peru Brazil & Suriname Brazil & Uruguay Brazil & Venezuela 1000000 Figure 1.4 shows the bilateral trade flow between Brazil and the other countries included in the equation. Just like figure 1.3 the blue line represents 1986 and the red line represents 1995. The choice of including this figure (in addition to figure 1.3.) was to show for another Mercosur country how the trade has been affected because of Mercosur. The results are very similar to figure 1.3 but this figure shows that trade has generally increased with other large countries (Mexico & Chile), meaning that it necessarily isn’t the entry of Mercosur that has increased the bilateral trade flow between the different countries. 25 12. Analysis In this following section, the results from this essay will be compared with previous studies. It will also be determined whether or not there is a specific correlation between the bilateral trade flow of country-pairs in Latin America and the explanatory variables mentioned in the essay. The study performed in this essay shows through the econometric estimations that the entry in specifically Mercosur leads to an increase concerning the bilateral trade flow. When looking at the figures presented in the previous sections it is evident that the membership of ALADI has also contributed to an increased bilateral trade flow for the countries involved, but because of the multicollinearity problem this has been hard to show econometrically. Even though there is proven correlation between a few of the explanatory variables and the dependent variable, there is far too much data in comparison to the amount of years the time interval is spread over to get exact results. This meaning that it is hard to generally point out that a country-pair will definitely trade more with each other just because they share a language or a border. The only proven part is, as earlier mentioned, that an entry in Mercosur will definitely lead to an increased bilateral trade flow. The study that Cèline Carrère performed (see section 3) came to the conclusion that when preferential trade agreements are formed, the consequence is that trade between the country-pairs that are in matter increases, however at the cost of the entire world trade decreasing. After receiving the results from the estimation in this essay, a conclusion that has to be drawn is that the results are rather similar to the ones of Carrères’ study. In both of the first two performed regressions the entry of a PTA who’s an increased bilateral trade flow, however it is hard to see just from the estimations that this will affect the rest of the world negatively. When looking at the figures however (section 11) it is apparent that the non-members of the PTAs are affected negatively from the formation of the two preferential trade agreements. The first regression is considered as the trust worthiest because of the presence of the fixed effects regarding both the countries and the period. The fixed effects have replaced the dummy variables in the two different estimations. When looking at the study performed by Carillo & Li (see section 3), in some ways the results resemble one another, when comparing to this essay. Carillo & Li regarded 26 both the Andean community and Mercosur. However, they didn’t focus on the bilateral trade flow between country-pairs, instead they focused on intra-trade and intra-industrialization, meaning that they not only had a different focus field but they also left out non-members of the preferential trade agreements. The conclusion that Carillo & Li managed to reach was that the entry of Mercosur proved to enhance the capital-intensive reference price products. Since the gravity equation wasn’t used in their study, the results can be slighter harder to compare than with Carrères study. Nevertheless, the results from the study performed in this essay shows the correlation between the bilateral trade flow and the MERC variable, which means that the entry of Mercosur as a matter of fact also had an effect on trade (in this essay’s estimation). Even though the effect from the entry of Mercosur only had a slight positive effect in Carillo & Li’s study, the effect still was evident, leading to the conclusion of their study’s results being in a way rather similar by the results in this essay. 27 13. Conclusion That the formation of ALADI and Mercosur has increased the bilateral trade flows for the members and decreased the same dependent variable for the non-members has been proven, not least in the analysis. Earlier studies have also proven that an introduction of preferential trade agreements has increased the trade between the member countries at the expense of the “outside world”. The point of this study was to see how an introduction of a PTA affected both the members and non-members, as well as find out if there is any correlation between any of the chosen variables (from the gravity model of trade) and the bilateral trade flow between the chosen country-pairs. When the regressions had been performed, it was evident that the variables that had a correlation with the bilateral trade flow of the country-pairs were ln(GDP per capita)it and MERC. This then meant that there was correlation between the membership of Mercosur and the bilateral trade flow. However, by looking at section 11 the figures show slightly more correlation. In all four cases it is shown that an entry of a PTA, regardless of if it’s ALADI or Mercosur, increases the bilateral trade flow between the members and that it decreases for the non-members. Since there isn’t any direct correlation for both of the PTAs (only for Mercosur) and bilateral trade flow, other factors must be taken into consideration. The bilateral trade flow has increased for all of the countries that have included in ALADI and basically for all of the Mercosur countries. Since the bilateral trade flow levels have increased, the conclusion that the countries have grown economically must be drawn. A lot of the countries in Latin America have been affected by the fact that Brazil has grown rapidly since 1975, meaning that the amount of goods and services traded automatically increase, which is reflected when looking at the figures of the four sample-countries. The main conclusion to be drawn from this study is that not one factor affects the bilateral trade flow of a country-pair; instead there are a number of factors that come into play and together they affect the trade. An introduction of a PTA has shown that the bilateral trade flow increases for the members, specifically Mercosur. The statistics in this essay show that the trade in fact has increased for both Mercosur and ALADI. Another factor that also affects the trade flow is time. With time countries have managed to grow, increasing their consumption, leading to a larger trade market, 28 which then has lead to the countries reaching higher GDPs and eventually larger values of bilateral trade flow. 29 14. Equation Estimate Figures 14.1. Fixed country effects and fixed period effects Dependent Variable: LNTFIJT Method: Panel Least Squares Date: 01/15/14 Time: 14:54 Sample: 1975 1995 Periods included: 21 Cross-sections included: 462 Total panel (unbalanced) observations: 9701 Variable Coefficient Std. Error t-Statistic Prob. C LN_GDP_PER_CAPITA_IT LN_GDP_PER_CAPITA_JT DISTIJ ALADIIJT MERCIJT -231088.1 20.22333 1.24E-05 69.71369 -1343.134 371728.0 226163.7 1.670049 9.73E-05 70.27487 4461.086 11542.71 -1.021774 12.10942 0.127243 0.992014 -0.301078 32.20458 0.3069 0.0000 0.8988 0.3212 0.7634 0.0000 Effects Specification Cross-section fixed (dummy variables) Period fixed (dummy variables) R-squared Adjusted R-squared S.E. of regression Sum squared resid Log likelihood F-statistic Prob(F-statistic) 0.600697 0.579636 95553.56 8.41E+13 -124761.0 28.52106 0.000000 Mean dependent var S.D. dependent var Akaike info criterion Schwarz criterion Hannan-Quinn criter. Durbin-Watson stat 30 31869.01 147378.5 25.82166 26.18210 25.94385 0.716794 14.2. Fixed period effects Dependent Variable: LNTFIJT Method: Panel Least Squares Date: 01/15/14 Time: 14:57 Sample: 1975 1995 Periods included: 21 Cross-sections included: 462 Total panel (unbalanced) observations: 9701 Variable Coefficient Std. Error t-Statistic Prob. C LN_GDP_PER_CAPITA_IT LN_GDP_PER_CAPITA_JT DISTIJ ADJIJ LANGIJ ALADIIJT MERCIJT -12221.58 16.51978 -1.41E-05 1.617029 98434.58 -24548.95 45619.93 467151.5 4033.145 1.290513 3.78E-05 0.756883 4207.109 2871.529 3859.097 13393.66 -3.030286 12.80094 -0.373991 2.136433 23.39720 -8.549087 11.82140 34.87857 0.0024 0.0000 0.7084 0.0327 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 Effects Specification Period fixed (dummy variables) R-squared Adjusted R-squared S.E. of regression Sum squared resid Log likelihood F-statistic Prob(F-statistic) 0.247880 0.245781 127992.0 1.58E+14 -127832.2 118.0735 0.000000 Mean dependent var S.D. dependent var Akaike info criterion Schwarz criterion Hannan-Quinn criter. Durbin-Watson stat 31 31869.01 147378.5 26.36021 26.38093 26.36723 0.504328 14.3. White test for heteroscedasticity Dependent Variable: LNTFIJT Method: Least Squares Date: 01/19/14 Time: 11:08 Sample: 1 9701 Included observations: 9701 White heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors & covariance Variable Coefficient Std. Error t-Statistic Prob. C LN_GDP_PER_CAPITA_IT LN_GDP_PER_CAPITA_JT DISTIJ ADJIJ LANGIJ ALADIIJT MERCIJT -14219.70 17.93427 -1.51E-05 1.566157 99511.99 -23708.40 39636.20 471033.0 3075.039 2.440599 3.04E-06 0.541237 5657.859 3318.584 3569.714 94893.82 -4.624234 7.348306 -4.988334 2.893665 17.58828 -7.144132 11.10347 4.963790 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0038 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 R-squared Adjusted R-squared S.E. of regression Sum squared resid Log likelihood F-statistic Prob(F-statistic) Prob(Wald F-statistic) 0.243968 0.243422 128192.0 1.59E+14 -127857.3 446.8410 0.000000 0.000000 Mean dependent var S.D. dependent var Akaike info criterion Schwarz criterion Hannan-Quinn criter. Durbin-Watson stat Wald F-statistic 32 31869.01 147378.5 26.36127 26.36719 26.36328 0.505789 115.2291 15. References 15.1. Websites URL 1: http://www.aladi.org/nsfweb/sitioIng/ Viewed: 2013-11-15 URL 2: http://www.macalester.edu/courses/geog61/chad/thefavel.htm Viewed: 2013-11-15 URL 3: http://www.sunat.gob.pe/customsinformation/tradeagreements/aladi.html Viewed: 2013-11-15 URL 4: http://www.itfglobal.org/itf-americas/ALADI.cfm/languageID/8 Viewed: 2013-11-15 URL 5: http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/8/4228/cap1.htm Viewed: 2013-11-15 URL 6: http://data.worldbank.org/region/LAC Viewed: 2013-11-20 URL 7: http://cepii.fr/CEPII/en/bdd_modele/bdd.asp Viewed: 2013-11-21 URL 8: http://en.mercopress.com/2012/12/08/bolivia-signs-mercosur-incorporation-protocoland-becomes-sixth-member Viewed: 2014-01-06 33 URL 9: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/06/30/us-mercosuridUSBRE85S1JT20120630 Viewed: 2013-12-17 URL 10 http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agracc/costarica/index.aspx Viewed: 2014-01-13 URL 11 http://www.lni.unipi.it/stevia/Organizzazioni/page03.html Viewed: 2014-01-15 URL 12 http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/customs-union.html Viewed: 2014-01-21 15.2. Authors/Studies Anderson, James E & van Wincoop, Eric (2003) “Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle”, Volume 93, Number 1, The American Economic Review Arabmazar, A. and P. Schmidt (1981) "Further evidence on the roubstness of the Tobit estimator to heteroscedasticity." Journal of Econometrics, p. 258. Bergstrand, Jeffrey H. & Baier, Scott L. (2006) “Estimating the effects on free trade agreements on international trade flows using matching econometrics”, Clemson University, South Carolina, USA. Carillo, Carlos & Li, Carmen A (2002) “Trade Blocks and the Gravity Model: Evidence from Latin American Countries” University of Essex, England Carrère, Cèline (2004) “Revisiting the effects of regional trade agreements on trade flows with proper specification of the gravity model”, Université d’Auvergne, France. Cyrus, Teresa L. (2010) “Income in the gravity model of bilateral trade: Does endogeneity matter?” The International Trade Journal, 16:2, 161-180 Devlin, Robert & Ffrench-Davis, Ricardo (1999) “Towards an Evaluation of Regional Integration in Latin America in the 1990s”. Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 34 Dougherty, Christopher (2011) “Introduction to Econometrics” 4th Edition, New York: Oxford University Press Inc. Frankel, Jeffrey A. (1998) “The Regionalization of World Economy” University of Chicago, Illinois, USA GATT: General agreement on tariffs and trade (1982) “Latin American Integration Association” Limited Distribution, Montevideo, Uruguay Hurd, M. (1979) "Estimation in truncated samples when there is heteroscedasticity." Journal of Econometrics” 11: 247-58. Martin, Will & Pham, Cong S. (2008) “Estimating the gravity model when zero trade flows are frequent” Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia Persson, Maria (2013) “Lecture Notes: Economic Integration” Lund University, Lund, Sweden Solimano, Andres (2005) “Economic Growth in Latin America in the late 20th century: evidence and interpretation”. Santiago, Chile February Westerlund, Joakim (2005). “Introduktion till ekonometri”, Lund: Studentlitteratur AB White, Halbert (1980) “A heteroscedasticity Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test of Heteroscedasticity”, Econometrica, Vol. 48, pp. 817-818. Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. (2013). “Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach” (Fifth international ed.). Australia: South-Western. p. 82–83 35 16. Appendix 16.1. Included Countries: Country Language ALADI Mercosur Argentina Spanish Yes Yes Belize English No No Bolivia Spanish Yes No Brazil Portuguese Yes Yes Chile Spanish Yes No Colombia Spanish Yes No Costa Rica Spanish No No Cuba Spanish No No Dominican Republic Spanish No No Ecuador Spanish Yes No El Salvador Spanish No No Guatemala Spanish No No Guyana English No No Honduras Spanish No No Mexico Spanish Yes No Nicaragua Spanish No No Panama Spanish Yes No Paraguay Spanish Yes Yes Peru Spanish Yes No Suriname Dutch No No Uruguay Spanish Yes Yes Venezuela Spanish Yes Yes 36 16.2. Included Variables Variable Bilateral Trade Flow Source www.cepii.fr (Gravity Model) Unit of measurement US $ GDP World DataBank US $ Adjacent Countries Wikipedia Binominal (0/1) Language Wikipedia Binominal (0/1) ALADI/Mercosur Wikipedia Binominal (0/1) Bilateral Distance www.cepii.fr (Geodist tool) 37 Kilometres