British Medical Journal 1 - Baylor College of Medicine

advertisement

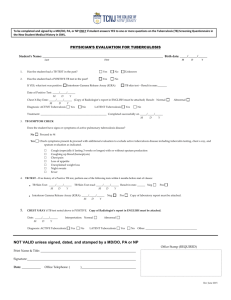

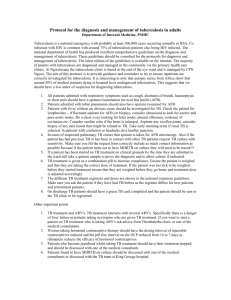

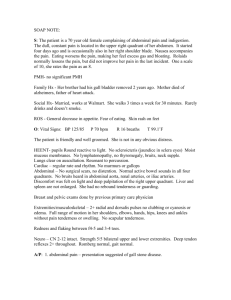

GI Grand Rounds Johanna Chan, PGY-5 Fellow Baylor College of Medicine 6/5/2014 Mentors: Dr. Kalpesh Patel Dr. Prasun Jalal No conflicts of interest No financial disclosures HPI • Reason for consult: jaundice, abdominal pain • 33yo healthy woman with hypothyroidism, admitted with 1 week of subacute RUQ abdominal pain, N/V, jaundice, dark urine, and acholic stools • Similar episode 2005, resolved spontaneously • Worse with food • Subjective fever, no chills, rigors, weight loss PMHx: – Hypothyroid – No known prior liver disease Medications: − Synthroid 75 mcg PSHx: None FamHx: – Mother: alive/well – Father: alive/well – No liver disease or autoimmune disease Allergies: NKDA SocHx – No EtOH, IVDA, nasal cocaine, blood transfusions, tattoos – Never smoker – Physician, originally from Bolivia – No recent needle exposures, antibiotics, unusual food exposures – Travel to California 1/2014, Bolivia 2012, Europe 2008 – One household cat Physical Exam T 98.2, BP 112/67, HR 78, RR 12, O2 sat 98% RA Gen: NAD, AAOx4, well-appearing HEENT: +slight scleral icterus, PERRL, EOMI, MMM, OP clear CV: RRR no m/r/g Chest: CTAB no wheezes, slight crackles at bases Abd: soft, nondistended, nontender, NABS, no organomegaly Ext: WWP, no clubbing, cyanosis, or edema Neuro: oriented x4, conversational Labs on admission 140 107 3.6 27 Total prot 8.4 Albumin 4.7 Total bili 1.4 Direct bili 1.0 Alk phos 401 ALT 330 AST 172 12 0.63 82 5.6 11.1 263 33.2 47% PMNs 37% lymphs INR 1.0 LDH 139 MCV 87 Imaging • CXR “normal” three years ago (exposed to TB previously as a medical student) • RUQ U/S – Normal liver size 12.4 cm, normal echogenicity, smooth contour – Normal spleen size 9 cm – Gallbladder sludge – No gallbladder wall thickening nor pericholecystic fluid – CBD 9 mm, CHD 7 mm Clinical course • ERCP: smooth biliary stricture, CBD stent – Brushing: rare atypical cells; interpretation limited by poor cellular preservation and low cellularity • EUS/biopsy of porta hepatis mass: – Extensively fragmented tissue containing granulomas with focal necrosis – No diagnostic dysplasia or malignancy – Stains negative for bacterial or fungal organisms – Ziehl Neelsen stain negative for acid fast organisms Next diagnostic steps? Clinical course • Diagnostic laparoscopy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and robotic periportal lymph node dissection and lymphadenectomy • Evidence of chronic cholecystitis • Posterior to CBD, well-formed and encapsulated periportal lymph node with granulomatous features • No evidence of miliary TB nor other intraabdominal pathology Pathology • Periportal lymph node, biopsy • Benign lymph node with noncaseating granulomas • AFB stain negative for mycobacteria • GMS stain negative for fungal organisms Additional labs CA 19-9 21 CA 125 9 CEA <0.5 AFP 4 IgG 1197 IgG4 4.1 IgM 140 Anti-smooth muscle Ab <20 Alpha 1 AT 190 Ceruloplasmin 43 HIV (−) Quantiferon TB (+) PPD (+) Blood cultures (−) Urine culture (−) Surgically biopsied lymph node: <1+ WBCs No organisms AFB smear negative AFB culture negative at 42 days Fungal smear negative Fungal culture negative at 28 Obstructive jaundice secondary to extrinsic biliary compression Working diagnosis: Intra-abdominal tuberculosis in the immunocompetent patient Clinical questions • What are clinical features of abdominal tuberculosis (ATB)? • What are diagnostic modalities and yield for abdominal tuberculosis? • What are mechanisms for obstructive jaundice in abdominal tuberculosis? Clinical questions • What are clinical features of abdominal tuberculosis (ATB)? • What are diagnostic modalities and yield for abdominal tuberculosis? • What are mechanisms for obstructive jaundice in abdominal tuberculosis? Clinical features of ATB • 1985 to 1992 showed a resurgence of TB in the U.S., coincident with AIDS epidemic • TB incidence in U.S. declining since 1992 • Global prevalence of TB estimated at 32%; WHO estimates > 2 billion people • Percentage of U.S. cases occurring in foreignborn persons is increasing (53% in 2003) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in tuberculosis – United States, 1998-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:2009-14. Dye C et al. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA 1999; 282: 677-86. Clinical features of ATB • Extrapulmonary TB accounts for 15-20% of cases in low-HIV prevalence areas • Of these, abdominal tuberculosis accounts for 11% - 16% in non-HIV patients, or 1-3% of the total TB • Much higher frequency of extrapulmonary disease in HIV patients – up to 50-70% International standards for tuberculosis care (WHO). 2006 Jan. Uygur-Bayramicli O et al. 2003 May; 9(5):1098-101. Wang HS et al. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998; 2: 569-574. Clinical features of ATB • Primary infection from reactivation of a dormant focus acquired somewhere in the past • Secondary disease: spread via swallowed sputum, ingestion of unpasteurized milk, or spread hematogenously or from an adjacent organ Clinical features of ATB • Prior to routine pasteurization of milk, abdominal tuberculosis was not uncommon in the UK. • Between 1912 and 1937 some 65,000 people died of tuberculosis contracted from consuming milk in England and Wales alone. Wilson, GS (1943), British Medical Journal 1 (4286): 261. Author Year Country No. of patients Mamo JP et al. 2013 UK 17 Tan KK et al. 2009 Singapore 57 Chen HL et al. 2009 Taiwan 21 Ramesh J et al. 2008 UK 86 Akinkuollie AA et al. 2008 Nigeria 47 Tarcoveanu E et al. 2007 Romania 22 Khan R et al. 2006 Pakistan 209 Bolukbas C et al. 2005 Turkey 88 Uzunkoy A et al. 2004 Turkey 11 Uygur-Bayramicli O et al. 2003 Turkey 31 Rai S et al. 2003 UK 36 Muneef et al. 2001 Saudi Arabia 46 Clinical features of ATB • Enteric, peritoneal, nodal, or solid visceral (liver, spleen, pancreas, kidney) • Intestinal involvement (colon, TI) most common, ranges from 40 – 75% of abdominal TB – Abdominal pain, bleeding, change in bowel habit, weight loss – Ulcerative or hypertrophic lesions, nodules, circumferential thickening on colonoscopy • Tuberculous peritonitis – Greater risk in patients with HIV or cirrhosis – Ascites, abdominal pain, fever – SAAG < 1.1 g/dL, exudative, lymphocytic-predominant Khan R et al. 2006 Oct 21;12 (39):6371-5. Riquelme A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006 Sep; 40(8): 705-10. Uygur-Bayramicli O et al. 2003 May;9(5):1098-101. Clinical features of ATB • • • • • • • Abdominal pain (28 – 90%) Fever (5 – 64%) Weight loss (5 – 60%) Nausea and vomiting (30 – 40%) Ascites (20 – 35%) Diarrhea (10 – 17%) Active pulmonary TB or prior pulmonary TB lesion (17 – 27%) • Anemia in 10 – 11 g/dL range • ESR elevated in 50 – 60 mm/H range Clinical questions • What are clinical features of abdominal tuberculosis (ATB)? • What are diagnostic modalities and yield for abdominal tuberculosis? • What are mechanisms for obstructive jaundice in abdominal tuberculosis? Diagnosis of abdominal TB • DDx intra-abdominal malignancy, abdominal lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s), hepatitis, chronic pancreatitis, PUD • Anemia and elevated ESR/CRP are the most common laboratory findings • Nonspecific clinical features, laboratory findings, variable radiographic findings • Microbiologic yield specific, not sensitive Bolukbas C et al. BMC Gastroenterol 2005; 5:21. Khan R et al. 2006 Oct 21;12 (39):6371-5. Mamo JP et al. Q J Med 2013 Apr; 106(4):347-54. Rai S et al. J R Soc Med 2003; 96:586-8. Diagnosis of abdominal TB • Constellation of clinical and radiographic features • Highest yield for surgically obtained specimen (laparotomy/laparoscopy), followed by CT/US guided biopsy and endoscopy • Many authors suggest therapeutic trial with antitubercular therapy • However, cannot recommend routine empiric antitubercular therapy – May delay diagnosis of malignancy, lymphoma, Crohn’s, etc. – Adverse effects with hepatitis, drug interactions, etc. not uncommon Khan R et al. 2006 Oct 21;12 (39):6371-5. Mamo JP et al. Q J Med 2013 Apr; 106(4):347-54. Rai S et al. J R Soc Med 2003; 96:586-8. Diagnostic yield in abdominal TB • AFB smear from samples insensitive (yield 0% 6%) • AFB culture insensitive (yield 7% in large series) • Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT, e.g. PCR) insensitive (7.1%) and in meta-analysis, insensitive for extrapulmonary disease • IFN gamma release assay (IGRA, e.g. Quant TB) tests usually negative; unclear role for diagnosis of active TB • Supportive histology most helpful (>90% surgical specimen, 50-80% endoscopic specimen) Dinnes J et al. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11:1-196. Khan R et al. 2006 Oct 21;12 (39):6371-5. Mamo JP et al. Q J Med 2013 Apr; 106(4):347-54. Clinical questions • What are clinical features of abdominal tuberculosis (ATB)? • What are diagnostic modalities and yield for abdominal tuberculosis? • What are mechanisms for obstructive jaundice in abdominal tuberculosis? Case: obstructive jaundice due to TB • TB of pancreas itself may cause pseudoneoplastic obstructive jaundice • TB lymphadenitis may cause extrinsic CBD compression (smooth narrowing of CBD) • Biliary TB itself may cause strictures, mimicking cholangiocarcinoma • TB may cause retroperitoneal mass leading to biliary obstruction Colovic R et al. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14 (19): 3098-3100. Take home points • Maintain a high index of suspicion, especially in patients from TB-endemic countries • Obtain samples for AFB and mycobacterial culture (laparotomy, laparoscopy, endoscopy) • Microbiology is specific but extremely insensitive • Multidisciplinary approach including ID and surgery • Empiric antitubercular treatment is not routinely recommended References Bolukbas C et al. Clinical presentation of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV seronegative adults. BMC Gastroenterol 2005; 5:21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in tuberculosis – United States, 1998-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:2009-14. Colovic R et al. Tuberculous lymphadenitis as a cause of obstructive jaundice: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2008 May 21; 14 (19): 3098-3100. Dinnes J et al. A systematic review of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of tuberculosis infection. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11:1-196. Dye C et al. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA 1999; 282: 677-86. Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis: the Indian contribution. Indian J Gastroenterol 1998; 17: 141-147. Khan R et al. Diagnostic dilemma of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients: an ongoing challenge for physicians. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Oct 21;12 (39):6371-5. International Standards for Tuberculosis Care (WHO). Endorsed by IDSA. Published January 2006. Accessed online 6/4/14 http://www.idsociety.org/uploadedFiles/IDSA/GuidelinesPatient_Care/PDF_Library/International%20TB.pdf References (continued) Mamo JP et al. Abdominal tuberculosis: a retrospective review of cases presenting to a UK district hospital. Q J Med 2013 Apr; 106(4):347-54. Misra SP et al. Colonic tuberculosis: clinical features, endoscopic appearance, and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 14: 723-729. Muneef MA et al. Tuberculosis in the belly: a review of forty-six cases involving the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001; 36: 528-532. Murphy TF et al. Biliary tract obstruction due to tuberculous adenitis. Am J Med 1980; 68: 452454. Rai S et al. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: the importance of laparoscopy. J R Soc Med 2003; 96:586-8. Riquelme A et al. Value of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in ascitic fluid for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006 Sep; 40(8): 705-10. Singhal A et al. Abdominal tuberculosis in Bradford, UK: 1992-2002. Eur J Gastroentrol Hepatol 2005; 17: 967-971. Sheer TA et al. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2003; 5:273-278. Sinan T et al. CT features in abdominal tuberculosis: 20 years experience. BMC Medical Imaging 2002; 2: 3-16. Uygur-Bayramicli O et al. A clinical dilemma: abdominal tuberculosis. 2003 May;9(5):1098-101. Uzunkoy A et al. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: experience from 11 cases and review of the literature. 2004 Dec 15; 10(24):3647-9. Wang HS et al. The changing pattern of intestinal tuberculosis: 30 years’ experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998; 2: 569-574. Wilson, G. S. (1943), “The Pasteurization of Milk,” British Medical Journal 1 (4286): 261. Questions or comments?