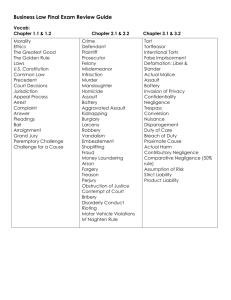

Blom_Law_140_-_Torts_Fall_2013_Rachel_Lehman

advertisement