9.5 Market conduct: Auctions

advertisement

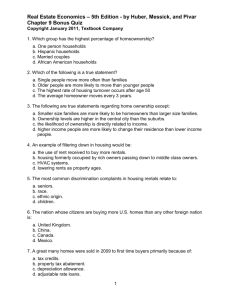

100 80 Where? How? When? What? Why? 2015 60 East West North 40 20 0 1st Qtr 2nd Qtr 3rd Qtr 4th Qtr Who? Managerial Economics Stefan Markowski Market research and market analysis The economics of competitive advantage Detailed course schedule Day no Topic Textbook ch. 1 (24 Nov; 3 hrs) 1. Introduction. Decision making process and its elements. The scope of economic decision making. Application of marginal analysis Chs. 1-2 2 3 3 3 2. Demand analysis and demand elasticities Ch. 3 3. Buyer product valuation and choices. Consumer surplus. Buyer pricing decisions Ch. 4 4 (27 Nov; 2 hrs) 4. Production/transformation process. Production technologies and input-output structure Ch. 5 5 (28 Nov; 2 hrs) 5. Cost structure and cost drivers of producer pricing strategies. Production scale and scope. Chs. 5 and 7 6 (1 Dec; 3 hrs) 6. Structure-conduct-performance. Market structures: competition and contestability. Pricing strategies of buyers and sellers Ch. 8 7 (2 Dec; 3 hrs) 7. Market structures: monopoly/monopsony, monopolistic competition and oligopoly. Pricing strategies and strategic behaviour Chs. 9-10 8 (3 Dec; 3 hrs) 8. Input sourcing and investment. Pricing and market power Chs. 6 and 11 9 (4 Dec; 2 hrs) 9. Decision making under conditions of uncertainty. Informational asymmetries and risk management Ch. 12 10 (5 Dec; 2 hrs) 10. Market research and market analysis. Auction and rings. Strategic behaviour Ch. 13 11 (8 Dec; 2 hrs ) 12 (9 Dec; 2 hrs) 11. Public sector perspective Ch. 14 13 (11 Dec; 2 hrs) Examination (25 Nov; hrs) (26 Nov; hrs) 12. Revision 13. Examination Topic 10: Market research and market analysis, Auction and rings Strategic behaviour Topic Contents 9.1 Managerial perspective 9.2 Understanding structure 9.3 Understanding conduct 9.4 Understanding performance 9.5 Market conduct: Auctions 9.6 Further reading 9.1 Managerial perspective • Firms make decisions with reference to their operational environment, i.e., rivals, suppliers, customers and labour markets • They measure the competitiveness of their industry by looking at various measures of industry concentration, the higher concentration the less competitive it is • They are also concerned with the size of other firms (turnover, employment, capitalisation), industrial leadership (who dominates), conditions of entry and exit, mergers and takeovers, and so on 9.1 Managerial perspective • In other words, they are interested in Structure, Conduct and Performance of a market/industry • The structure-conduct-performance paradigm is used to discuss industry growth and sustainable competitive advantage • In practical applications in management this has been adapted by Michael Porter as the Five Forces Framework for industry/market analysis: – Entry conditions – Industry rivalry – Substitute and complementary products – Power of input suppliers – Power of buyers 9.2 Understanding structure Firm size • Firm size is an indicator of its influence, possible dominance and terms of entry/exit. Size matters • Google and look up the annual Fortune Largest 2000 Global Companies, which not only ranks the largest companies but also contains links to each company’s annual report Industry concentration • The concentration of largest firms in the industry’s total turnover/sales is a measure of its competitiveness 9.2 Understanding structure • Concentration ratios measure the proportion of sales or production attributed to the largest firms • Four firm concentration ratio C4 = (S1+ S2+ S3+ S4) / ST, where Si is sales of the firm i ST total sales of all firms in the industry/market wi = Si / ST C4 = (w1+ w2+ w3+ w4) 9.2 Understanding structure • Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) is the sum of the squared market shares of firms in a market multiplied by 10,000 to avoid decimals HHI = 10000 S (wi)2 and wi = Si / ST • It takes the value between 0 (all firms very small and very numerous so nearly 0% shares) and 10,000 (only one firm with 100% share) • Instead of T measuring all firms in a market or an industry we can focus on the top 50 or 100 Technology • Various technology related indices e.g., R&D shares in costs or sales 9.2 Understanding structure Capitalisation measures • We can use the number of workers/operatives per $1 million of sales or capital-labour ratios Demand conditions • This is to capture demand characteristics of a market or an industry • Rothschild index measures the ratio of own price elasticity of demand for the total market, T, to the own price elasticity of demand for an individual firm, Fi, R = ET / EFi • It takes values between 0 and 1 (similar elasticities) 9.2 Understanding structure Entry/exit barriers • Measures of capital intensity • Patents • Economies of scale 9.3 Understanding conduct Pricing behaviour of rivals • Lerner index L = (P-MC) / P, where P is price and MC is the marginal cost • When P=MC L=0 as P-MC increases L 1 • This can be rearranged as P= (1 / (1 – L) ) MC, where 1 / (1 – L) is the markup factor • Recall MR = P ((1 + E) / E), where E is own price elasticity of demand and MR is marg. revenue P = MR (E/(1+E)) and to max profits MR = MC by manipulation L = 1 – E / (1+E) 9.3 Understanding conduct Mergers and acquisitions • Different mergers and acquisitions can occur in a market/industry: – Vertical integration – Horizontal integration (economies of scale) – Conglomerate integration (economies of scope) Advertising • Spending on advertising reflects the competitiveness of a market/industry R&D • A function of technical change and competition 9.4 Understanding performance Profitability • Profitability ratios Rent seeking • Stakeholders ’ (e.g., workers, bankers) ability to capture rents Social benefit • This measures the impact of a market/industry on social welfare (all of us) • Dansby-Willig preformance index ranks markets/ industries by the degree of an incremental increase in output would increase s. welfare (if 0 no change if >0 improvement) 9.5 Market conduct: Auctions • In an auction, buyers compete directly (bid) for the right to buy a good or service • Types of auctions – English auction – bidders observe bids of other bidders and respond by increasing their bid or abstaining from bidding the auction ends when only a single bidder remains and is successful if his/her offer price exceeds the seller’s reservation price – First-price sealed-bid auction – bidders made written offers (or electronic) and the highest bid wins if the offer price exceeds the seller’s reservation price – Second-price sealed-bid auction – bidders made written offers (or electronic) and the highest bid wins but pays the offer of the next highest bidder (if the offer price exceeds the seller’s reservation price) 9.5 Market conduct: Auctions – Dutch auction – the auctioneer begins with a high price and bids it down to the highest acceptable offer • In principle, bids in the English and Dutch auctions should end up at the same level but in reality the auction dynamics could be different as people are emotional • The optimal bidder strategy for an English auction is to set a reservation (own valuation) price and bid no more than that • In a second-price sealed bid auction the bidder’s best strategy is to make a written offer equal his/her reservation price 9.5 Market conduct: Auctions • This is an interesting auction it is the second mouse that sets the bid but the first mouse gets the cheese • The optimal strategy is more complicated for the first-price sealed-bid auction and the Dutch auction – generally one should bid less than one’s reservation offer price • Winner’s curse occurs when the winning bidder overestimates the true value of the item and bids too much – do not copycat other people’s valuation • Gambler’s ruin – when a series unfavourable outcomes occurs in a row 9.5 Market conduct: Auctions • When you assess the value of items you wish to make an offer for you must decide whether it is an essentially private (subjective) valuation independent of other people’s assessments or not. Do you buy it for your own enjoyment or resale? • At some auctions all bidders may wish to use the same valuation (e.g., when they bid to buy and resell the item), but they do not know what to pay. Here they may influence each other and value the item higher (set higher reservation price) when they see other bidders bid more (learning by bidding could be expensive) 9.6 Further reading Baye (2010): chs. 7 and 12