Literary Theory: Definition, Approaches, History, Examples

advertisement

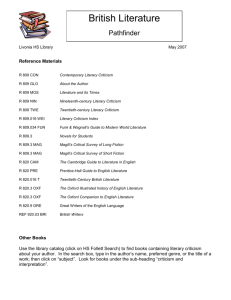

Literary Theory Definition, Approaches, History, Examples Literary criticism as a systematic study “It is clear that criticism cannot be a systematic study unless there is a quality in literature which enables it to be so. We have to adopt the hypothesis, then, that just as there is an order of nature behind the natural sciences, so literature is not a piled aggregate of 'works' but an order of 'words'.” Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (1957) Vassilis Lambropoulos, David Neal Miller , eds. Twentieth-Century Literary Theory: An Introductory Anthology David Lodge, 20th century literary criticism: a reader (1972) http://www.sunypress.edu/p-861-twentieth-century-literary-theo.aspx http://books.google.com/books/about/20th_century_literary_criticism.ht ml?id=WSMaAQAAIAAJ Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983) Raman Selden, Peter Widdowson, Peter Brooker, A reader's guide to contemporary literary theory (1985; 5th edition 2005) http://books.google.com/books?id=QNmFm4M_RXkC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs _ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, http://books.google.com/books?id=6TZ2iVrS6MgC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q& From theories to Theory English Literature as a discipline was designed and consolidated during the second half of the 19th century (it was a consequence of the coming of the national dimension into prominence) Canon construction, canon as a national narrative Historical, biographical, moral and rhetorical considerations were blended As an academic discipline it started to develop in a way to meet scientific criteria From theories to Theory New Criticism New Criticism was a movement in literary theory that dominated American and had an impact on English literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. Its chief critical strategy was close reading, particularly when discussing poetry, emphasizing that a work of literature functions as a self-contained, self referential aesthetic object. From theories to Theory New Criticism New Criticism developed in the 1920s-30s and peaked in the 1940s-50s. The movement is named after John Crowe Ransom's 1941 book The New Criticism. New Critics focused on the text of a work of literature and tried to exclude the author's biography and intention, historical and cultural contexts, and moralistic bias from their analysis. Reader's response was not taken into account either. From theories to Theory New Criticism New Critics often performed a "close reading" of the text and believed the structure and meaning of the text were intimately connected and should not be analyzed separately. The main aim of New Criticism was to make literary criticism scientific. From theories to Theory New Criticism In 1954, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley published a classic and controversial New Critical essay entitled "The Intentional Fallacy", in which they argued strongly against the relevance of an author's intention, or "intended meaning" in the analysis of a literary work. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, the words on the page were all that mattered; importation of meanings from outside the text was considered irrelevant, and potentially distracting. From theories to Theory New Criticism In another essay, "The Affective Fallacy”, which served as a kind of sister essay to "The Intentional Fallacy„ Wimsatt and Beardsley also discounted the reader's personal/emotional reaction to a literary work as a valid means of analyzing a text. This fallacy would later be repudiated by theorists from the reader-response school of literary theory. From theories to Theory New Criticism The popularity of the New Criticism persisted through the Cold War years in both American high schools and colleges, in part, because it offered a relatively straightforward (and politically uncontroversial) approach to teaching students how to read and understand poetry and fiction. To this end, Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren published Understanding Poetry and Understanding Fiction which both became standard pedagogical textbooks in American high schools and colleges during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. From theories to Theory New Criticism Studying a passage of prose or poetry in New Critical style required careful, exacting scrutiny of the passage itself. Formal elements such as rhyme, meter, setting, characterization, and plot were used to identify the theme of the text. In addition to the theme, the New Critics also looked for paradox, ambiguity, irony, and tension to help establish the single best and most unified interpretation of the text. Such an approach has been criticized as constituting a conservative attempt to isolate the text and to shield it from external, political concerns such as those of race, class, and gender. Robert Frost (1874-1963) Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year. Frost cont. He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound's the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake. The woods are lovely, dark and deep. But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep. From theories to Theory New Criticism One of the most common grievances against the New Criticism, is an objection to the idea of the text as autonomous; detractors react against a perceived anti historicism, accusing the New Critics of divorcing literature from its place in history. From theories to Theory New Criticism Another objection comes from the reader-response school of theory, rightly claiming that the fundamental close reading technique is based on the assumption that the subject and the object of study - the reader and the text - are stable and independent forms, rather than products of the unconscious process of signification. From theories to Theory I. A. Richards I. A. Richards (1893–1979) was an English literary critic. His books, especially Principles of Literary Criticism (1924) and Practical Criticism (1929), proved to be founding influences for the New Criticism. The concept of 'practical criticism' led in time to the practices of close reading, what is often thought of as the beginning of modern literary criticism. Richards is regularly considered one of the founders of the contemporary study of literature in English. From theories to Theory I. A. Richards In Practical Criticism he advocated an empirical study of literary response. He removed authorial and contextual information from thirteen poems, including one by Longfellow and four by decidedly marginal poets. Then he assigned their interpretation to undergraduates at Cambridge University in order to ascertain the most likely impediments to an adequate response. This approach had a startling impact at the time in demonstrating the depth and variety of misreadings to be expected of otherwise intelligent college students as well as the population at large. From theories to Theory I. A. Richards The question arises, however, whether such interpretations are misreadings or relevant varieties of reading. From theories to Theory René Wellek and Austin Warren’s Theory of Literature was much ahead of its time when it was first published in 1949. By the 1970s and 80s the term “study of literature” was getting to be substituted by the term “theory” and soon taken over by “Theory” with capital T. From theories to Theory Theory has a history and is categorized into schools, such as – roughly in the order of their appearance – Liberal Humanism, New Criticism, Formalism, Structuralism, Marxist, Psychological Approach, Archetypal Approach, Myth Criticism, Cultural Criticism, Post-structuralism, Deconstruction, New Historicism, Reader-Response Criticism, Hermeneutic Approach, Phenomenological Criticism, Postmodernism, Postcolonialism, Feminism, Gender Studies, Queer Theory, Ecocriticism, etc. Structuralism Structuralism originated in the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure and the subsequent Prague and Moscow schools of linguistics. Just as structural linguistics was facing serious challenges from the likes of Noam Chomsky and thus fading in importance in linguistics, structuralism appeared in academia in the second half of the 20th century and grew to become one of the most popular approaches in academic fields concerned with the analysis of language, culture, and society. Marxist literary criticism Marxist literary criticism is a loose term describing literary criticism based on socialist and dialectic theories. Marxist criticism views literary works as reflections of the social institutions from which they originate. According to Marxists, even literature itself is a social institution and has a specific ideological function, based on the background and ideology of the author. Marxist literary criticism The simplest goals of Marxist literary criticism can include an assessment of the political 'tendency' of a literary work, determining whether its social content or its literary form are 'progressive'. It also includes analyzing the class constructs demonstrated in literature. William Blake (1757-1827) The Chimney Sweeper When my mother died I was very young, And my father sold me while yet my tongue Could scarcely cry 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep. There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head, That curled like a lamb's back, was shaved: so I said, "Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head's bare, You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair." And so he was quiet; and that very night, As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight, That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack, Were all of them locked up in coffins of black. Blake cont. And by came an angel who had a bright key, And he opened the coffins and set them all free; Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run, And wash in a river, and shine in the sun. Then naked and white, all their bags left behind, They rise upon clouds and sport in the wind; And the angel told Tom, if he'd be a good boy, He'd have God for his father, and never want joy. And so Tom awoke; and we rose in the dark, And got with our bags and our brushes to work. Though the morning was cold, Tom was happy and warm; So if all do their duty they need not fear harm. Structuralism The structuralist mode of reasoning has been applied in a diverse range of fields, including anthropology, sociology, psychology, literary criticism, and architecture. The most prominent thinkers associated with structuralism include the linguist Roman Jakobson, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, the philosopher and historian Michel Foucault, the philosopher and social commentator Jacques Derrida, and the literary critic Roland Barthes. Structuralism Proponents of structuralism would argue that a specific domain of culture may be understood by means of a structure - modelled on language - that is distinct both from the organizations of reality and those of ideas or the imagination. In the 1970s, structuralism was criticized for its rigidity and ahistoricism. New Historicism New Historicism is a school of literary theory, grounded in critical theory, that developed in the 1980s, primarily through the work of the critic Stephen Greenblatt. New Historicists aim simultaneously to understand the work through its historical context and to understand cultural and intellectual history through literature, which documents the new discipline of the history of ideas. Deconstruction Deconstruction is a term introduced by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his 1967 book Of Grammatology. Deconstruction refers to a process of exploring the categories and concepts that history and tradition have imposed on a word or a work. Deconstruction suggests analysis with high precision. Deconstruction In describing deconstruction, Derrida famously observed that "there is nothing outside the text." That is to say, all of the references used to interpret a text are themselves texts, even the "text" of reality as a reader knows it. There is no truly objective, non-textual reference from which interpretation can begin. Deconstruction, then, can be described as an effort to understand a text through its relationships to various contexts. Post-structuralism The post-structuralist movement may be broadly understood as a body of distinct responses to Structuralism. Structuralism argued that human culture may be understood by means of a structure - modeled after structural linguistics - that is distinct both from the organizations of reality and the organization of ideas and imagination. Post-structuralism The post-structuralist approach includes the rejection of the self-sufficiency of the structures that structuralism posits and an interrogation of the binary oppositions that constitute those structures. Reader-response criticism Reader-response criticism is a school of literary theory that focuses on the reader (or "audience") and his or her experience of a literary work, in contrast to other schools and theories that focus attention primarily on the author or the content and form of the work. Although literary theory has long paid some attention to the reader's role in creating the meaning and experience of a literary work, modern reader-response criticism began in the 1960s and '70s, particularly in America and Germany, in works by Stanley Fish, Wolfgang Iser, Hans-Robert Jauss, Roland Barthes, and others. Reader-response criticism An important predecessor was I. A. Richards, who in 1929 analyzed a group of Cambridge undergraduates‘ misreadings. Reader-response theory recognizes the reader as an active agent who constitutes meaning to the work and completes its meaning through interpretation. Reader-response criticism argues that literature should be viewed as a performing art in which each reader creates his or her own, possibly unique, text-related performance. Reader-response criticism vs New Criticism Reader-response criticism stands in total opposition to the theories of formalism and the New Criticism, in which the reader's role in re-creating literary works is ignored. New Criticism had emphasized that only that which is within a text is part of the meaning of a text. No appeal to the authority or intention of the author, nor to the psychology of the reader, was allowed in the discussions of orthodox New Critics. Psychoanalytic criticism Psychoanalytic literary criticism refers to literary criticism or literary theory which, in method, concept, or form, is influenced by the tradition of psychoanalysis begun by Sigmund Freud. Psychoanalytic reading has been practised since the early development of psychoanalysis itself, and has developed into a heterogeneous interpretive tradition. Ecocriticism Ecocriticism is the study of literature and environment from an interdisciplinary point of view where all sciences come together to analyze the environment and brainstorm possible solutions for the correction of the contemporary environmental situation. Ecocriticism is an intentionally broad approach that is known by a number of other designations, including "green (cultural) studies", "ecopoetics", and "environmental literary criticism". From theories to Theory Delia Da Sousa Correa and W. R. Owens: The Handbook to Literary Research. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2010 Theory exerts an institutional pressure. Students of literature are supposed to understand that their various projects must demonstrate an awareness of Theory. Theory is a dominant academic discourse, a body of knowledge that should be acquired and applied. From theories to Theory Theory is not a given field of knowledge with many ‘schools’ which has to be sampled and picked from and applied, but is an institutional extrapolation from an ongoing process of debating and thinking about literature and criticism. Theories If so, can any work be analyzed by any method and critical perspective ↕ ↕ ↕ Certain works are more suitable for an analysis according to a particular method or critical perspective Critical approaches Wilfred L. Guerin, Earle Labor, Lee Morgan, Jeanne C. Reesman, John R. Willingham: A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature. 4th ed. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Oress, 1999 M. H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition (1953) Introduction: Orientation of Critical Theories The literary work examined in relation to or examined the world the audience the author in itself The literary work in relation to: UNIVERSE WORK OF ART AUTHOR AUDIENCE The literary work in relation to: Work of art – universe: How art reflects / mirrors / represents the world e.g., realism (or the effect of the real) Work of art – artist: How the artist creates, what it is the artist expresses The literary work in relation to: Work of art – audience What effect the work of art has / should have Work of art – in itself: What it is like (formal, structural analyses) Mimetic theories Mimesis and imitation rather: representation Aristotle’s Poetics: dramatic plot as imitation of an action Coleridge: imitation of nature in being an organic unity Realistic imitation: recognizable (it is like what the reader knows) Aristotle: imitation: an internal relation of form to content, vs an external relation of copy and original You are aware of the resemblance of tragic action to human behaviour and you are aware of the conventions of tragic drama as different from other forms Pragmatic theories 1970s: reader-response criticism, Literary Pragmatics: reader’s contribution to text reading actualizes potential meaning 18th century: art has to be useful "The end of writing is to instruct; the end of poetry is to instruct by pleasing,“ (Samuel Johnson's Preface to Shakespeare) Follows classical theory of rhetoric (= art of persuasion) 5 part process: invention, arrangement, style, memory, delivery Expressive theories Art as an expression of feelings: “For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” William Wordsworth in “Preface to Lyrical Ballads” (1800) Art as an expression of the personal subconscious Sigmund Freud, “The Interpretation of Dreams” (1900) → psychoanalytical criticism Art as an expression of the collective unconscious C.G. Jung, archetypes, archetypal images Objective theories The work of art studied in itself, as a closed system: internal structure, form, internal consistency - its "intrinsic" rather than "extrinsic" qualities. art for art’s sake (l’art pour l’art) No one theory can explain all works (The essay is an introduction to his book on the Romantics: The Mirror and the Lamp, 1953 M.H. Abrams, “Orientation of critical theories” mimetic theories objective theories expressive theories pragmatic theories textual criticism The editorial art - establishing the text “The aim of a critical edition should be to present the text, so far as the available evidence permits, in the form in which we may suppose that it would have stood in a fair copy, made by the author himself, of the work as he finally intended it.” W. W. Greg, The Editorial Problem in Shakespeare (rev. edn. Oxford 1954) authorial intention A design or plan in the author's mind: “We argued that the design or intention of the author is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of literary art, and it seems to us that this is a principle which goes deep into some differences in the history of critical attitude.” “The Intentional Fallacy” by W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe C. Beardsley (1946) In: The Verbal Icon: studies in the meaning of poetry (also In: Lodge's 2Oth c. Literary Criticism) impressionistic criticism Recreate the poem while writing about the poem. “The Affective Fallacy is a confusion between the poem and its results (what it is and what it does) [...] It begins by trying to derive the standard of criticism from the psychological effects of the poem an ends in impressionism and relativism. [...] Plato's feeding and watering of the passions was an early example of affective theory, and Aristotle's countertheory of catharsis was another” “The Affective Fallacy” by W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe C. Beardsley (1949) In: The Verbal Icon: studies in the meaning of poetry (also In: Lodge's 20th c. Literary Criticism) value judgements “Literary criticism has in the present day become a profession, - but it has ceased to be an art. Its object is no longer that of proving that certain literary work is good and other literary work is bad, in accordance with rules which the critic is able to define. English criticism at present rarely even pretends to go so far as this. It attempts, in the first place, to tell the public whether a book be or be not be worth public attention; and, in the second place, so to describe the purport of the work as to enable those who have not time or inclination for reading to feel that by a short cut they have become acquainted with its contents. Both these pojects, if fairly well carried out, are salutary.” Anthony Trollope, Autobiography (1883), ch. xiv interpretation “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art... The temptation to interpret Marienbad should be resisted. What matters in Marienbad in the pure, untranslateable, sensuous immediacy of some of its images, and its vigorous if narrow solution to certain problems of cinematic form... In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation (1967) deconstructing interpretations We need to interpret interpretations more than to interpret things. (Montaigne) Quoted in Jacques Derrida, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” [1967], Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (London: Routledge Classics, 2001) page 351-370:351. An example: gender studies • Mimetic approach: the way the work represents gender issues in society • Pragmatic approach: the way the work can help raising awareness and show alternative models of relating to gender issues • Expressive approach: the way the author expresses the experience of being a woman, a man, a human being of a specific gender • Objective approach: e.g.,écriture féminine (an aside about basic terms) • female ≠ feminine ≠ feminist biological vs socio-cultural vs political context and terminology • feminism ≠ gender studies - political vs academic context and terminology, - focus on women vs focus on gendered experience of being human • feminist literary criticism • gender studies in literature Gender as performance Judith Butler Gender Trouble, 1990 Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex, 1993 Carol Ann Duffy (1955) Sit at Peace When they gave you them to shell and you sat on the back-doorstep, opening the small green envelopes with your thumb, minding the queues of peas, you were sitting at peace. Sit at peace, sit at peace, all summer. When Muriel Purdy, embryonic cop, thwacked the back of your knees with a bamboo-cane, mouth open, soundless in a cave of pain, you ran to your house, a greeting wean, to be kept in and told once again. Nip was a dog. Fluff was a cat. They sat at peace on a coloured-in mat, so why couldn’t you? Sometimes your questions were stray snipes over no-man’s land, bringing sharp hands and the order you had to obey. Sit – Duffy, cont. At – Peace! Jigsaws you couldn’t do or dull stamps didn’t want to collect arrived with the frost. You would rather stand with your nose to the window, clouding the strange blue view with your restless breath. But the day you fell from the Parachute Tree, they came from nowhere running, carried you in to a quiet room you were glad of. A long silent afternoon, dreamlike. A voice saying peace, sit at peace, sit at peace. Another example: adaptation theory “My method has been to identify a text-based issue that extends across a variety of media, find ways to study it comparatively, and then tease out the theoretical implications from multiple textual examples. At various times, therefore, I take on the roles of formalist semiotician, poststructuralist deconstructor, or feminist and postcolonial demythifier; Linda Hutcheon but at no time do I (at least consciously) try to impose any of these theories on my examination of the texts or the general issues surrounding adaptation. All these perspectives and others, however, do inevitably inform my theoretical frame of reference” Hutcheon, Linda (2009-04-04). “Preface” to A Theory of Adaptation . T & F Books US. Kindle Edition. Linda Hutcheon … It is the very act of adaptation itself that interests me, not necessarily in any specific media or even genre.… My working assumption is that common denominators across media and genres can be as revealing as significant differences. Linda Hutcheon ….A Theory of Adaptation begins its study of adaptations as adaptations; that is, not only as autonomous works. Instead, they are examined as deliberate, announced, and extended revisitations of prior works. Because we use the word adaptation to refer to both a product and a process of creation and reception, this suggests to me the need for a theoretical perspective that is at once formal and "experiential." Linda Hutcheon …This book is not, however, a history of adaptation, though it is written with an awareness of the fact that adaptations can and do have different functions in different cultures at different times. A Theory of Adaptation is quite simply what its title says it is: one single attempt to think through some of the theoretical issues surrounding the ubiquitous phenomenon of adaptation as adaptation.” Linda Hutcheon A Theory of Adaptation Routledge, 2006 The language of literary criticism “A statement may be used for the sake of the reference, true or false, which it causes. This is the scientific use of language. But it may also be used for the sake of the effects in emotion and attitude produced by the reference it occasions. This is the emotive use of language.” I.A. Richards, “The two uses of language” (ch. 34 from The Principles of Literary Criticism (1924) also in Lodge's 20th Century Literary Criticism