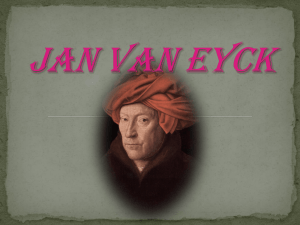

Northern Renaissance Self-Portraits: van Eyck

advertisement

NORTHERN RENAISSANCE SELF-PORTRAITS: VAN EYCK AND VAN HEMESSEN Amanda Pina Northern Renaissance Professor Houghton April 2, 2013 [Type text] [Type text] Pina 2 The art of portraiture during the Northern Renaissance was in a constant state of change. There was a movement away from the classical motifs and towards a more “northern” style, full of symbolism. For a long time portraits were only painted of the wealthy aristocrats. These images were heavily influenced by classical coinage, dating back to the era of Constantine, who was always portrayed in profile. The profile view became a symbol of high status and wealth, and so it is no wonder that the aristocrats of the day wanted to be depicted in the same light.1 There was also a movement away from the idealization of classical imagery. Artists in northern Europe preferred realism in their paintings and generally took pride in their depictions of even the most minute details. However, some levels of realism were not seen as being as important as the symbolism found in the images. Because art was made for the educated upper class the symbolism was often complex and influenced again by the ancient Greeks and Romans of the classical period. The only way to understand classical symbolism was to read about it, and only the upper class had the resources to do that. In 1433 things began to change. Jan van Eyck painted The Man in the Red Turban, which many scholars believe to be a portrait of the artist himself. If that belief is true then it is the first freestanding self-portrait ever created. Some scholars believe that it is of van Eyck because of the red turban, which is thought to be the traditional garb of artists during that time.2 This belief is solidified by van Eyck’s knowledge of the ancient writings of Pliny, who wrote the Naturalis Historia. His book tells the story of the court 1 2 Meiss, 'Nicholas Albergati,' 138. Kleiner, "High Renaissance and Mannerism in Northern Europe and Spain," 431. [Type text] [Type text] Pina 3 of Alexander the Great, which are the historical figures that van Eyck based multiple paintings on. In this particular portrait he compares himself, the painter on the court of Phillip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, to Apelles, the painter on Alexander’s court.3 This kind of conflation put him not only on the same level as Apelles, who was considered to be the greatest painter that ever lived, but also as the aristocracy of his time. Artists were not seen as high-ranking figures in society during van Eyck’s time, so painting a portrait suggesting otherwise was a huge step forwards. Caterina van Hemessen took the same initiative when it came to raising the status of women artists. There were very few existing at the time, and those who did exist only did because a family member taught them the trade, women did not go to art schools or have apprenticeships. In the case of Caterina her father, Jan Sanders van Hemessen, taught her.4 Therefore, because she was a painter and taught a “man’s trade” by her father, the overwhelming iconography of her portrait was seen as quite masculine. Like van Eyck, van Hemessen also drew inspiration from the stories of Pliny. In his Naturalis Historia he told of a woman named Marcia who invented the modeling of figures by tracing her lover’s shadow. Even while achieving such a high status as an artist she is described as maintaining her womanly nature. She was portrayed in Netherlandish art the way she was described, and Caterina drew inspiration from that imagery by conflating herself with Marcia.5 Marcia was shown standing at an easel making a self-portrait in Boccaccio’s De Mulieribus Claris from 1475. Caterina chose to mimic the composition from that piece, Preimesberger, “Paragons and Paragone,” 28. "Caterina Van Hemessen." 5 King, “Looking a Sight,” 383. 3 4 [Type text] [Type text] Pina 4 but instead of using it to accurately tell portray the story of a historical account she needed it to verify her status as an artist and prove that she had really painted the portrait herself.6 She is noted as the first artist, male or female, to paint a portrait of herself seated and working at an easel.7 Another way that Caterina proved that she made the work herself was by including an inscription, which was an element of art typical to that time period. It read, “Caterina of the Hemessen family, aged twenty: I painted myself, 1548.” The words were written in Latin, a language that only well educated people in the Netherlands would be able to read.8 They were the only ones that needed to be convinced of her skill as an artist. Van Eyck founded the act of signing a work with an inscription in a notable fashion, as a prominent part of the painting that was meant to be seen. In his self-portrait he inscribed the Greek letters, “ΑΛΣ ΙΧΗ ΧΑΝ.” When the letters are translated it reads, “Als Ich Can,” which means, “As I can do.” This inscription can be interpreted in multiple ways. One way to look at it is meaning, “It’s the best I can do,” which has a very humble feeling about it. Others might see it as more of a brag, reading, “As only I can do,” like it would not have been possible for anyone else to create. Another way to read it is to pronounce “Ich” like Eyck and therefore read it like, “As only Eyck can do.” No matter what way you choose to say it, it is a clear declaration that he is the one who created the portrait and he wants people to know it. King, “Looking a Sight,” 386. "Caterina Van Hemessen." 8 King, “Looking a Sight,” 386. 6 7 [Type text] [Type text] Pina 5 One obvious difference between the two inscriptions, other than the language they are written in, is the way that they are presented. Caterina places the words as though they are magically floating in the air in the top left of the painting. On the other hand, van Eyck takes the inscription as an opportunity to show off his skills as a painter. He establishes a clear paragone with frame makers by using black and white to “sculpt” the fame right from the wooden picture panel.9 The light and shadow that he creates make the frame appear to come forward into the viewer’s space. In reality the surface of the panel is as smooth as glass. A similarity between the two inscriptions is that they are written as if they are presenting themselves to the viewer. This gives a kind of life to the images, as if they are real people sitting in front of the viewers introducing themselves. Another way van Eyck is able to make the portrait engage the viewer is by making the eyes gaze directly at the person.10 The three-quarter pose of the head adds to this illusion by making it seem like the portrait is making eye contact no matter what angle the viewer is looking from.11 It is almost as if the figure is seeing the viewer from another world right on the other side of the picture plane. Comparatively, the van Hemessen portrait lacks the same level of engagement. The figure is gazing at something outside of the fame, but it is as if she is looking right past the viewer at something else back in the distance. Van Eyck takes the eerie gaze of the eyes a step further by making the corneas a brilliant white and filling them with a network of pinkish-red capillaries. A thin layer of Preimesberger, “Paragons and Paragone,” 28. Meiss, 'Nicholas Albergati,' 138. 11 Kleiner, "High Renaissance and Mannerism in Northern Europe and Spain," 431. 9 10 [Type text] [Type text] Pina 6 naturalistic, clear liquid covering the eyes heightens their luminescence.12 He brings that same level of detail to every aspect of his paintings. There is an illusion of space created inside the fame because, even though the background is a flat pitch black, the vivid shading gives the figure an impression of soundness and solidity. The modeling of the flesh around the mouth and eyes is brutally honest and not at all idealized. Wrinkles are clearly visible as the skin is drawn in tight at the cheek and jawbones and left to sag around the jowls, temples, and eye sockets. There is also a clear tension in the muscles of the eyes, nostrils, and especially the mouth, with the figures thin lips compressed into an austere straight line.13 Viewers can also see a variety of contrasting textures in the painting. If one didn’t know better they might try to reach out and touch the soft fur on the coat collar, the prickly stubble on the figure’s face14, of the smooth surface of the red turban15, the bright hue of which also adds a stark contrast to the dark earth tones in the rest of the portrait. While Caterina van Hemessen’s portrait is also very naturalistic, it lacks some of the elements and extreme levels of detail of Jan van Eyck’s, which is relentlessly descriptive. A certain level of texture can be seen in the soft velvet surface of her clothes, however, there is not the same amount of modeling in the face, which appears to be as light and smooth as porcelain. Not a wrinkle can be found on her forehead or around the eyes and mouth. This suggests that the image is slightly more idealized. However, it does not appear that it was because the artist wanted to counter the assumed masculine iconography that came with being an artist. Through her plain clothing and Meiss, 'Nicholas Albergati,' 138. Meiss, 'Nicholas Albergati,' 141. 14 Meiss, 'Nicholas Albergati,' 141. 15 Meiss, 'Nicholas Albergati,' 138. 12 13 [Type text] [Type text] Pina 7 solemn expression Caterina showed that she does not want to appeal to male viewers in any way suggesting that she is ready for marriage. Though they do have their differences both of these works blazed a trail, developing a convention for many of the self-portraits of artists that followed. They both had to prove their skills to the people who were viewing their work16 because people tend to question new things and have a strong reaction to change. Caterina was faced with the challenge of prove the equality of women and showing her skill as an artist. This had to be done in such a way that would combat the attention of viewers who would enjoy self-portraits of women purely for their attractive appearance.17 Her success was celebrated by becoming the first women artist to achieve a court position, in 1556 from Mary of Hungary, Governor of the Netherlands.18 She also held good standing in the guild of St. Luke and eventually as the teacher of three male students. Yet, despite the stand she took with the risk of her self-portrait, historians believe her career as an artist ended after her marriage in 1554 because no more paintings by her exist from after that date.19 Van Eyck influenced the world of portraiture heaviest of all by inventing the freestanding self-portrait. He set a new standard for every artist that followed. This includes van Hemessen as well, whose self-portrait may never have happened had it not been for The Man in the Red Turban. Van Hemessen and van Eyck often painted for very different reasons, but they also shared a multitude of similarities. The each changed the idea of what was standard King, “Looking a Sight,” 398. King, “Looking a Sight,” 398. 18 King, “Looking a Sight,” 386. 19 "Caterina Van Hemessen." 16 17 [Type text] [Type text] Pina 8 in a portrait. The Renaissance in Northern Europe was constantly evolving under the influence of different artists and cultures. Both artists were able to stay ahead of the curve, while remaining true to their Netherlandish roots. [Type text] [Type text] Pina 9 Works Cited "Caterina Van Hemessen." N.p., n.d. Web. <www.saylor.org/site/wpcontent/uploads/.../Caterina-Van-Hemessen.pdf>. King, Catherine. Looking a Sight: Sixteenth-Century Portraits of Woman Artists. 3rd ed. Vol. 58. Berlin: Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, 1995. 381-406. JSTOR. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/1482820>. Kleiner, Fred S. "High Renaissance and Mannerism in Northern Europe and Spain." Gardner's Art Through the Ages. 14th ed. Vol. 2. Boston: Clark Baxter, 2010. 431. Print. The Western Perspective. Meiss, Millard. "'Nicholas Albergati' and the Chronology of Jan Van Eyck's Portraits." The Burlington Magazine 94.590 (1952): 137-46. JSTOR. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/870819>. Preimesberger, Rudolf. Paragons and Paragone: Van Eyck, Raphael, Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Bernini. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2011. Print.