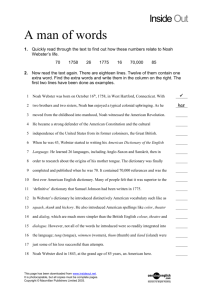

Noah Webster and The American Dictionary of English

advertisement

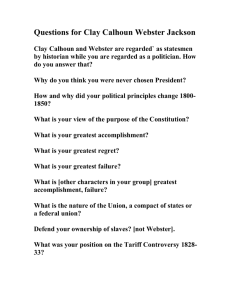

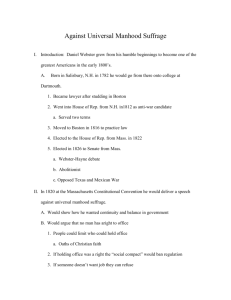

Noah Webster and the American Dictionary of the English Language “The author, it is well known, met with much opposition at the commencement of his labors; and it is equally notorious, that as he proceeded in the accomplishment of his design, he was seldom cheered with the voice of encouragement.” James Luce Kingsley, North American Review Heather McIlvaine Biography Born in 1758 on a farm in Connecticut He attended Yale and was exposed to the ideas of the Enlightenment In the winter of 1779-80 he became interested in education reform • 1783 the “blue-backed speller” • 1785 Dissertations on the English Language – suggested spelling and grammar reforms • 1800 first advertised for the American Dictionary – it was printed in 1828 Fought for copyright laws Died in 1843 Spelling Reform Webster believed that spelling reforms would contribute to the development of a national language He was aware that America was a nation of immigrants, and simplified spelling would aid them in learning the new language and lessen the differences in sectional dialects Benjamin Franklin supported Webster’s ideas • “You need not be concern’d in writing to me, about your bad Spelling, for in my Opinion, as our Alphabet now stands, the bad Spelling, or what is call’d so, is generally the best, as conforming to the Sound of the Letters and of the Words.” – letter to his sister, Jane Mecom, 1786 Proposed Alterations The omission of all superfluous or silent letters • (bread=bred, head=hed, give=giv, built=bilt, friend=frend, publick=public, neighbor=nabor) A substitution of a character that has a definite sound for one that is more vague and indeterminate • (mean=meen, grieve= greev, laugh=laf, daughter=dawter, character=karacter, machine=masheen, pique=peek, tour=toor) An alteration in character, or the addition of a point would distinguish different sounds, without the substitution of a new character • (ά, ė, ī) Example of “American Language” “In these essays, ritten within the last yeer, a considerable change in spelling iz introduced by way of experiment…The man who admits that the change of housbande…into husband, iz an improovement, must acknowledge also the riting of helth, breth, rong, tung, munth, to be an improovement. There iz no alternativ. Every possible reezon that could ever be offered for altering the spelling of wurds, still exists in full force; and if a gradual reform should not be made in our language, it will proov that we are less under the influence of reezon than our ancestors.” – Noah Webster, Collection of Essays and Fugitiv Writings, 1790 Inconsistencies in Webster’s Proposal He substitutes the voiced alveolar /z/ sound in “reason” and “is” with a “z” but does not make the same changes in the plurals “essays” and “words” The voiceless alveolar /s/ sound of the “c” in “ancestors” should be replaced with an “s” Webster’s proposal was met with widespread criticism His own inconsistencies demonstrate how ingrained the conventional methods of spelling were, and how difficult change would be. Eventually he stopped trying to introduce the extreme phonetic respelling of words, but he continued trying to remove silent letters. The Initial Reaction When Webster first proposed the dictionary it was received with condemnation • “If, as Mr. Webster asserts, it is true that many new words have already crept into the language of the United States, he would be much better employed in rooting out those anxious weeds, than in mingling them with the flowers.” – Joseph Dennie, Gazette of the United States, 1800. The political atmosphere of the time period was responsible for the failure • This was the era when the modern political parties formed Federalist Party: favored centralized government and opposed the extension of suffrage – Webster was a Federalist Republican Party: favored decentralized government and supported the extension of suffrage Webster was criticized both by federalists (for his decision to include common words) and by the republicans (for being a federalist) • “The lexicographer’s business is solely to collect, arrange and define the words that usage presents to his hands. He has no right to proscribe words; he is to present them as they are.” – Webster Writing the Dictionary Webster thought the process would take 5 years – by 1818, he was only on “B” To support his family while writing, he published the ill-received Compendious Dictionary • Radical orthography: groop, wimmen, tung • Common words like crock By the time Webster completed the American Dictionary in 1825 the Federalist Party was dead and populism was on the rise He had abandoned the spelling reforms • Dropped the “k” in words like “mimic” and the “u” in words like “favor” Its publication in 1828 came at the height of the Second Great Awakening • Webster used biblical references rather than literary quotes to define the words Instrument, n. 2…The distribution of the Scriptures may be the instrument of a vastly extensive reformation in morals and religion. All these factors helped make the dictionary a success despite the rocky beginning Etymology Like many lexicographers at the time, Webster was intrigued by the etymology of words His etymological research began around 1809, distracting him from working on the dictionary for almost 10 years His method of discerning etymology was based on the appearance of words • If the number of letters and basic structure of a word in one language was similar to that of another, he assumed that they carried the same meaning His etymological conclusions were founded on his strong religious beliefs • He believed the Bible was a factually reliable source to trace the origins of language Most current lexicographers dismiss his etymological conclusions Webster’s Effect on Today He believed that the misunderstanding of words led to social and political upheaval – they should not be used vaguely The politicization of words is evident in Webster’s struggle to find initial support for his dictionary, and in the definitions that were published • Politician n. – “of artifice or deep contrivance” It remains a politically heated issue • In 1961 the Merriam-Webster Dictionary released a notoriously permissive edition; the editorial staff settled decisions on words and usage by a show of hands “If nine-tenths of the citizens of the United states, including a recent President, were to use inviduous, the one-tenth who clung to invidious would still be right, and they would be doing a favor to the majority if they continued to maintain the point.” Dwight Macdonald • Nuclear v. Nucular Works Cited Lepore, Jill. “Noah’s Mark.” The New Yorker 6 Nov 2006: 78. Micklethwait, David. Noah Webster and the American Dictionary. London: McFarland, 2000. Rollins, Richard. The Long Journey of Noah Webster. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980.