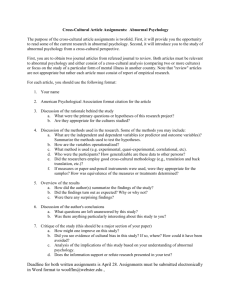

PowerPoint

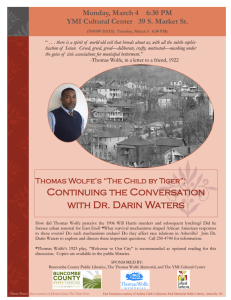

advertisement

Chapter 6 Conduct Problems Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Description of Conduct Problems Conduct problems and antisocial behaviors describe ageinappropriate actions/attitudes that violate family expectations, societal norms, or personal or property rights of others Diversity in disruptive/rule-violating behaviors ranges from annoying minor behaviors (e.g., temper tantrums) to serious antisocial behaviors (e.g., vandalism, theft, assault) Consider many types, pathways, causes, and outcomes Often associated with unfortunate family and neighborhood circumstances; circumstances do not excuse the behavior, but help us understand it Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Context, Costs, and Perspectives Context Antisocial behaviors appear and decline during “normal” development they vary in severity, from minor disobedience to fighting some antisocial behaviors decrease with age some increase with age and opportunity more common in boys in childhood, but the difference narrows in adolescence children who are the most physically aggressive in early childhood maintain their relative standing over time Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Context, Costs, and Perspectives (cont.) Social and Economic Costs Conduct problems are the most costly mental health problem in North America Early, persistent, extreme pattern of antisocial behavior occurs in about 5% of children; these children account for over 50% of crime in the U.S. and 30-50% of clinic referrals 20% of mental health expenditures in the U.S. are attributable to crime Public costs across healthcare, juvenile justice, and educational systems are at least $10,000 per child Lifetime cost to society per child who leaves high school for life of crime/substance abuse: about $2 million Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Context, Costs, and Perspectives (cont.) Perspectives Legal Juvenile delinquency: children who have broken a law Legal definitions result from apprehension and court contact, so they exclude antisocial behaviors of very young children occurring in home or school Minimum age of responsibility is 12 in most states and provinces Only a subgroup of children meeting legal definition of delinquency also meet definition of a mental disorder Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Context, Costs, and Perspectives (cont.) Perspectives (cont.) Psychological Conduct problems seen as falling on a continuous dimension of externalizing behavior 1 or more SD above the mean: conduct problems Externalizing behavior consisting of related but independent subdimensions: “rule-breaking behavior” “aggressive behavior” overt-covert dimension destructive-nondestructive dimension Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Context, Costs, and Perspectives (cont.) Psychiatric Conduct problems viewed as distinct mental disorders based on DSM symptoms In the DSM-IV-TR, conduct problems are described as persistent patterns of antisocial behavior, represented by categories of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) Public Health Blends the legal, psychological, and psychiatric perspectives with public health concepts of prevention and intervention Goal: reduce injuries, deaths, personal suffering, and economic costs associated with youth violence Cuts across disciplines Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning DSM-IV-TR: Defining Features Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) Age-inappropriate, stubborn, hostile, and defiant behaviors Usually appears by age 8 Many behaviors (e.g., temper tantrums) are common in young children, severe/age-inappropriate ODD behaviors can have extremely negative effects on parent-child interactions 75% of clinic-referred preschoolers from low-income families meet DSM criteria for ODD These children are at high risk for developing secondary mood, anxiety, impulse-control disorders Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning DSM-IV-TR: Defining Features (cont.) Conduct Disorder (CD) Repetitive, persistent pattern of severe aggressive and antisocial acts that involve inflicting pain on others or interfering with rights of others through physical/verbal aggression, stealing, or acts of vandalism severe antisocial behaviors may have co-occurring problems: ADHD, academic deficiencies, poor peer relations family child-rearing practices may contribute parents feel the children are out of control and feel helpless to do anything about it Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning DSM-IV-TR: Defining Features (cont.) Conduct Disorder (cont.) Age of onset: Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset CD Children with childhood-onset CD display at least one symptom before age 10 more likely to be boys more aggressive symptoms account for disproportionate amount of illegal activity persist in antisocial behavior over time Children with adolescent-onset CD are as likely to be girls as boys do not show the severity or psychopathology of the earlyonset group less likely to commit violent offenses or persist in their antisocial behavior over time Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning DSM-IV-TR: Defining Features (cont.) Conduct Disorder (cont.) CD and ODD have much overlap of symptoms Although most cases of CD are preceded by ODD, and most children with CD continue to display ODD symptoms, most children with ODD do not progress to more severe CD Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning DSM-IV-TR: Defining Features (cont.) Conduct Disorder (cont.) CD and Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) APD: pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others; involvement in multiple illegal behaviors As many as 40% of children with CD later develop APD Adults with APD may display psychopathy: a pattern of callous, manipulative, deceitful, remorseless behavior Signs of lack of conscience occur in some children as young as 3-5 years Subgroup of children with CD are at risk for extreme antisocial and aggressive acts; display callous and unemotional interpersonal style Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Associated Characteristics Cognitive and Verbal Deficits Although most children with conduct problems have normal IQ, they score nearly 8 points lower than peers Greater deficit for children with childhood-onset Verbal IQ consistently lower than performance IQ Deficits present before conduct problems and may increase risk Deficits in executive functioning related to failure to consider future implications of their behavior and its impact on others may be due to co-occurring ADHD Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Associated Characteristics (cont.) School and learning problems Underachievement, grade retention, special education placement, dropout, suspension, and expulsion Common factor (e.g., neuropsychological, language deficit, socioeconomic disadvantage) may underlie both conduct problems and school difficulties Early language deficits may cause communication difficulties, which may increase conduct problems in school Relationship between conduct problems and underachievement is firmly established by adolescence Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Associated Characteristics (cont.) Self-Esteem Deficits Low self-esteem is not the primary cause of conduct problems Instead, problems are related to inflated and unstable, and/or tentative view of self Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Associated Characteristics (cont.) Peer problems Verbal and physical aggression toward peers; poor social skills Often rejected by peers although some are popular children rejected in primary grades are 5 times more likely to display conduct problems as teens some become bullies often form friendships with other antisocial peers underestimate own aggression, overestimate others’ aggression toward them; reactive-aggressive children display hostile attributional bias: attribute negative intent to others proactive-aggressive view their aggressive actions as positive Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Associated Characteristics (cont.) Family Problems General family disturbances (e.g., parental mental health problems, family history of antisocial behavior, marital discord, etc.) Specific disturbances in parenting practices and family functioning (e.g., excessive use of harsh discipline, lack of supervision, lack of emotional support/involvement, etc.) High levels of conflict in the family, especially between siblings Lack of family cohesion and emotional support Deficient parenting practices Parental social-cognitive deficits Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Associated Characteristics (cont.) Health-Related Problems High risk for personal injury, illness, drug overdose, sexually transmitted diseases, substance abuse, and physical problems as adults Rates of premature death 3-4 times higher in boys with conduct problems Early onset of sexual activity, higher sex-related risks Illicit drug use associated with antisocial and delinquent behavior Conduct problems in childhood are a risk factor for adolescent and adult substance abuse Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Accompanying Disorders and Symptoms Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) About 50% of children with CD also have ADHD Possible reasons: common underlying factors, ADHD may be a catalyst for CD, or ADHD may lead to childhood onset of CD Depression and Anxiety About 50% of children with conduct problems also have a diagnosis of depression or anxiety Poor adult outcomes for boys with combined conduct and internalizing problems Girls with CD develop depressive or anxiety disorder by early adulthood Males and females: increasing severity of antisocial behavior is associated with increasing severity of depression and anxiety Anxiety may serve as protective factor to inhibit aggression Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Prevalence, Gender, and Course Prevalence ODD more prevalent than CD during childhood; by adolescence prevalence is equal Lifetime prevalence rates 10% for ODD (11% for males, 9% for females) 9% for CD (12% for males, 7% for females) Gender differences are evident by 2-3 years of age 2-4 times more common in boys; boys have earlier age of onset Gender disparity increases through middle childhood, narrows in early adolescence, and increases again in late adolescence, when male delinquent behavior peaks Early symptoms for boys are aggression and theft; early symptoms for girls are sexual misbehaviors Boys remain more violence-prone Sex differences in antisocial behavior have decreased by more than 50% over the past 50 years Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Prevalence, Gender, and Course (cont.) Explaining Gender Differences Possible explanations: genetic, neurobiological, environmental risk factors, definitions of conduct problems to include physical violence girls tend to use indirect, relational forms of aggression Clinically referred girls and boys are comparable in externalizing behavior; referred girls are more deviant than boys in relation to same-age, same-sex peers girls’ behavior is more covert Some girls with CD have early menarche Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Prevalence, Gender, and Course (cont.) Developmental Course and Pathways General Progression Earliest sign: usually difficult temperament in infancy Hyperactivity (possibly from neurodevelopmental impairments) Oppositional/aggressive behaviors that peak during preschool years Diversification: new forms of antisocial behavior develop over time Across cultures, more frequent during adolescence About 50% of children with early conduct problems improve; some don’t display problems until adolescence; some display persistent low-level antisocial behavior from childhood/adolescence through adulthood Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Prevalence, Gender, and Course (cont.) Developmental Course and Pathways (cont.) Two Common Pathways across cultures Life-course-persistent (LCP) path begins early and persists into adulthood; antisocial behavior begins early because neuropsychological deficits heighten vulnerability to antisocial environments in social environment Complete, spontaneous recovery is rare after adolescence family history of externalizing disorders Adolescent-limited (AL) path begins around puberty and ends in young adulthood (more common and less serious than LCP) 50% decrease by early 20s, 85% decrease by late 20s Negative adult outcomes, especially for those on the LCP path Male: criminal behavior, work problems, substance abuse Females: depression, suicide, health problems Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes Historically viewed as result of inborn characteristics or learned through poor socialization practices Early theories focused on child’s aggression and considered one primary cause Today conduct problems are seen as resulting from the interplay among predisposing child, family, community, and cultural factors operating in a transactional fashion over time Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Genetic Influences Aggressive and antisocial behavior in humans is universal Adoption and twin studies: 50% or more of variance in antisocial behavior is hereditary, with contribution higher for children with LCP versus AL pattern and for those with callous-unemotional traits Adoption and twin studies suggest contribution of genetic and environmental factors Genetic factors: difficult temperament, impulsivity, tendency to seek rewards, and insensitivity to punishment may create antisocial “propensity” may increase likelihood for child’s exposure to environmental risk factors genotype may moderate susceptibility to environmental insults Different pathways reflect the interaction between genetic and environmental risk and protective factors Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Prenatal Factors and Birth Complications Pregnancy and birth factors low birthweight malnutrition (possible protein deficiency) during pregnancy lead poisoning mother’s use of nicotine, marijuana, other substances during pregnancy maternal alcohol use during pregnancy no direct biological link between biological factors and conduct problems Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Neurobiological factors Overactive behavioral activation system (BAS) and underactive behavioral inhibition system (BIS) Variations in stress-regulating mechanisms (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and autonomic nervous system (ANS), serotonergic functioning, and structural and functional deficits in prefrontal cortex) Those with early-onset CD show low psychophysiological/ cortical arousal, and low reactivity of ANS, which may lead to diminished avoidance learning so that punishment may increase, rather than decrease, antisocial behavior Low levels of cortical arousal/low autonomic reactivity Neural, endocrine, psychophysiological influences interact with negative environmental circumstances Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Social-Cognitive Factors Immature forms of thinking (e.g., egocentrism and lack of perspective taking) Cognitive deficiencies (e.g., inability to use verbal mediators to regulate behavior) Cognitive distortions (e.g., interpreting neutral events as hostile) Dodge and Pettit: comprehensive social-cognitive framework model involving cognitive and emotional processes as mediators Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Family Factors Combination of child risk factors and extreme deficits in family management skills are associated with persistent/severe forms of antisocial behavior Influence of family environment (e.g., physical abuse, marital conflict) on child moderated by several factors; child’s genotype moderates the link between maltreatment and antisocial behavior Reciprocal influence: child’s behavior is influenced by and influences the behavior of others Coercion theory: through a 4-step, escape-conditioning sequence, the child learns to use increasingly intense forms of noxious behavior to avoid unwanted parental demands Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Family Factors (cont.) In children with callous-unemotional traits, CD persists regardless of parenting quality Insecure parent-child attachments Family instability and stress High family stress may be both a cause and an outcome of child’s antisocial behavior Childhood-onset CD (not adolescent-onset CD) related to unemployment, low SES (poverty), multiple family transitions Amplifier hypothesis: stress amplifies parents’ maladaptive predispositions Parental criminality and psychopathology Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Societal Influences Individual/family factors interact with larger societal/cultural context Social disorganization: community structures impact family processes that affect child adjustment Adverse contextual factors associated with poor parenting Neighborhood and school: antisocial behavior in youth is more common in neighborhoods with criminal subcultures social selection hypothesis Media: correlation between media violence and antisocial behavior Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Causes (cont.) Cultural Factors Across cultures, socialization of children for aggression is one of the strongest predictors of aggressive acts Rates of antisocial behavior vary widely across and within cultures Antisocial behavior is associated with minority status in the U.S., but this is likely due to low SES Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Treatment and Prevention • Typically, treatment begins when severe antisocial behavior at school leads to referral, although it may begin sooner • The most promising treatment uses a combination of approaches across many settings • Some treatments are not very effective: • office-based individual counseling and family therapy • group treatments can worsen the problem • restrictive approaches (residential treatment, inpatient hospitalization, incarceration) • Comprehensive two-pronged approach includes: • early intervention/prevention programs • ongoing interventions Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Treatment and Prevention (cont.) • Interventions with some empirical support for success: Parent management training (PMT) (effective for children under 12) minimal or no direct intervention by therapist parents learn to change parent-child interactions, promote positive behavior, decrease antisocial behavior parents learn to identify, define, observe child’s problem behaviors treatment sessions cover use of commands, rules, praise, rewards, mild punishment, negotiation, contingency contracting parents see/practice techniques homework helps generalize skills progress is monitored/adjusted as needed Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Treatment and Prevention (cont.) Problem-Solving Skills Training (PSST) Focuses on cognitive deficiencies and distortions in interpersonal situations Used along and in combination with PMT, as necessary Underlying assumption: the child’s perceptions and appraisals of environmental events trigger aggressive and antisocial responses; changes in faulty thinking lead to changes in behavior Therapist uses instruction, practice, and feedback Children learn to appraise the situation, identify selfstatements and reactions, alter their attributions about others’ motivations, and learn to be more sensitive to others Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Treatment and Prevention (cont.) Multisystemic Treatment (MST) Intensive family- and community-based approach for adolescents with severe conduct problems who are at risk for out-of-home placement Sees adolescents as functioning within interconnected social systems Antisocial behavior results from/is maintained by transactions within or between any of the systems Attempts to empower caregivers to improve youth and family functioning Effective in reducing long-term rates of criminal behavior in part by decreasing association with deviant peers Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Treatment and Prevention (cont.) Preventive Interventions Recognition that intensive home- and school-based interventions help overcome negative developmental history, poor family/community environment, and deviant peer associations Main assumptions: problems treated more easily/effectively in younger than older children counteracting risk factors/strengthening protective factors at young age limits/prevents escalation of problem behaviors reduces costs to educational, criminal justice, health, and mental health systems Fast Track: program to prevent problems in high-risk children Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning Treatment and Prevention (cont.) Conclusion: The degree of success or failure in treating antisocial behavior depends on the type and severity of the child’s conduct problem and related risk and protective factors Mash/Wolfe Abnormal Child Psychology, 4th edition © 2009 Cengage Learning