Criminal Procedure as the Balance Between Due Process and

advertisement

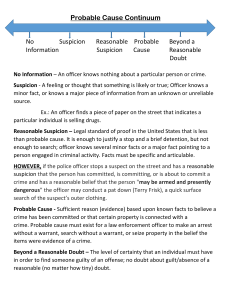

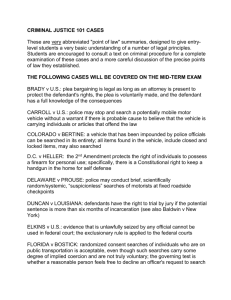

Criminal Procedure for the Criminal Justice Professional 11th Edition John N. Ferdico Henry F. Fradella Christopher Totten Stop and Frisks Chapter 8 Prepared by Tony Wolusky History An officer’s power to detain and question suspicious persons dates back to English common law. The U.S. Supreme Court adopted formal guidelines governing street encounters amounting to less than arrests or full searches in three 1968 cases. 1. 2. 3. Terry v. Ohio Sibron v. New York Peters v. New York The Three Foundational Cases In Terry v. Ohio, Sibron v. New York, and Peters v. New York (1968), the court applied a balancing test under the reasonableness requirement of the Fourth Amendment. In Terry v. Ohio, the Court recognized the officer’s need to protect themselves when suspicious circumstances indicate possible criminal activity by potentially dangerous persons, even if probable cause is lacking. Stops and frisks are more limited than a full search and are judged by a less rigid standard than probable cause. Reasonable suspicion is all that is needed. The Reasonableness Standard The determination of the reasonableness of stops and frisks involves balancing a person’s right to privacy and right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures against the governmental interests of effective crime prevention and detection and the safety of law enforcement officers and others from armed and dangerous persons. Differentiating Stops as Seizures from Non-Seizures Not all stops are seizures. The Supreme Court in United States v. Mendenhall (1980) established the free to leave test—a “totality-ofcircumstances” approach that assesses whether or not a reasonable person would have believed that he was not free to leave. Only when an officer intentionally, by means of physical force or show of authority, has restrained a person’s liberty has a “seizure” occurred. Also, for a seizure to occur, the person being confronted by the officer must have submitted to the officer’s authority or force. Authority to Stop A law enforcement officer may stop and briefly detain a person for investigative purposes if the officer has a reasonable suspicion supported by articulable facts of ongoing, impending, or past criminal activity. Reasonable suspicion is less than probable cause. Reasonable suspicion may develop based on logical deductions from human activity based on an officer’s observations, knowledge, experience, and training (not a mere hunch). Bases for Forming Reasonable Suspicion Reasonable suspicion may also be derived from: Information from known informants Information from Anonymous informants Information from police flyers, bulletins, or radio dispatches Information from Known Informants A law enforcement officer may stop a person based on an informant’s tip if, under the totality of the circumstances, the tip, plus any corroboration of the tip by independent police investigation, carries enough indicia of reliability to provide reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. Information from Anonymous Informants An anonymous tip that a particular person at a particular location is carrying a gun is not, without more information, sufficient to justify law enforcement officers in stopping and frisking that person. Information from Police Flyers, Bulletins, or Radio Dispatches A law enforcement officer may stop a person on the basis of a flyer, bulletin, or radio dispatch issued by another law enforcement agency as long as the issuing law enforcement agency has a reasonable suspicion that the person named in the flyer, bulletin, or dispatch is or was involved in criminal activity. Permissible Scope of a Stop An investigative stop must last no longer than is reasonably necessary and must use the least intrusive methods reasonably available to confirm or dispel an officer’s suspicions of criminal activity. Ordering Driver and Passengers Out of a Vehicle An officer who has lawfully stopped a motor vehicle may order both the driver and passengers out of the vehicle pending completion of the stop. Reasonable Investigative Methods During a Stop If an officer has reasonable suspicion to justify a stop of a person, and that person subsequently refuses in violation of state law to identify herself, the officer may be permitted to expand the scope of the detention by arresting the person. Time Issues The time taken for a stop must be reasonable. Courts consider the law enforcement purposes to be served and the time reasonably needed to effectuate those purposes. Stops should be initiated immediately. However, a short delay in making the stop may be justified in certain situations. Use of Force An officer making a stop must use an objectively reasonable degree of force or threat of force. Stop Arrest Purpose Brief investigatory detention. To bring a suspect into custody as the prelude to criminal prosecution. Justification Reasonable suspicion. Probable cause. Warrant Not needed Preferred for arrests in public places. Required to enter a suspect's home. Search warrant needed to enter a third-party's home. Notice None required. Requires notice that the person is under arrest and that the officer has the authority to arrest. Force Reasonable degree of force. Deadly force may only be used if, during the stop, it becomes necessary to act in self-defense or defense of others. Reasonable degree of force. Deadly force may be used if it becomes necessary to act in self-defense or defense of others or if needed to stop a fleeing felon from escaping if the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a threat of serious bodily harm either to the officer or to others. Time limit Temporary. No longer than necessary. Whatever is reasonably necessary to arrest and bring the suspect into custody for further processing Judicial Review No automatic right to prompt judicial review of the legality of the stop. Prompt judicial review of the legality of the arrest by a neutral judicial officer is required. Search Allowed Protective pat-down frisk of outer clothing for weapons may be conducted if, and only if, the officer has reason to believe that the person stopped is armed and dangerous. A full body search of the arrestee for weapons and evidence may be conducted as a search incident to any valid, custodial arrest. Officers may also search the areas of arrestee’s immediate control. Defining “Frisk” A frisk is a limited search of a person’s body consisting of a careful exploration or patdown of the outer surfaces of the person’s clothing in an attempt to discover weapons. A frisk protects the officer and others from possible violence by persons being investigated for crime. Limited Authority to Frisk Frisks are based on reasonable suspicion. The officer must have reason to believe that the individual is armed and dangerous. Justification to frisk usually requires a combination of one or more factors, evaluated in the light of an officer’s experience and knowledge. Scope of a Frisk A frisk must initially be limited to a pat-down of a person’s outer clothing. If a weapon or weapon-like object is detected or if a non-threatening object’s identity as contraband is immediately apparent to an officer’s sense of touch, the officer may reach inside clothing or a pocket and seize the object. Non-threatening contraband (i.e., drugs) must be immediately apparent to an officer’s sense of touch, and the officer must have probable cause, upon feeling the object, that the object is this kind of contraband. Scope of a Frisk of Motor Vehicle Occupant If a law enforcement officer has a reasonable suspicion that a motor vehicle’s occupant is armed and dangerous, the officer may frisk the occupant and search the passenger compartment of the vehicle for weapons. The officer may look in any location in the passenger compartment that a weapon could be found or hidden. The officer may also seize items of evidence other than weapons, if discovered in plain view during the course of such a search. Factors Justifying a Frisk Behavioral and evidentiary factors include: The suspected crime involves weapons. The suspect is nervous, edgy, or belligerent. There is a bulge in the suspect’s clothing. The suspect’s hand is concealed in his or her clothing. The suspect does not present satisfactory identification or an adequate explanation for suspicious behavior. The suspect behaves in a secretive, or furtive, fashion. The officer is in an area known to have armed persons. The officer believes that the suspect may have been armed on a previous occasion. Detentions of Containers and Other Property A law enforcement officer may detain property for a brief time if the officer has a reasonable, articulable suspicion that the property contains items subject to seizure. The officer may not search the property without a search warrant or probable cause during an emergency. The property may be subjected to a properly conducted “canine sniff.” An officer’s physical manipulation of a person’s belongings without reasonable suspicion that there is criminal evidence within it is unreasonable. Traffic Stops and Roadblocks A law enforcement officer may not stop a motor vehicle and detain the driver to check license and registration unless the officer has reasonable, articulable suspicion of criminal activity or unless the stop is conducted in accordance with a properly conducted highway checkpoint program. Involves balancing the gravity of the public concerns served by the seizure, the degree to which the seizure advances the public interest, and the severity of the interference with individual liberty. Racial Profiling Many states and the federal government have rules prohibiting racial profiling by law enforcement officers. Many states require law enforcement agencies to collect statistical data on racial profiling. Courts are increasingly receptive to arguments by plaintiffs that they have been targets of racial profiling, and may exclude evidence or subject offending officers to civil rights lawsuits. Detentions, the USA PATRIOT Act, and the War on Terror The USA PATRIOT Act permits the indefinite detention of enemy combatants who are non-U.S. citizens, including permanent resident aliens, if the United States Attorney General certifies that he has “reasonable grounds to believe” that the non-citizen has engaged in terrorist activity. Detentions, the USA PATRIOT Act, and the War on Terror The USA PATRIOT Act permits the indefinite detention of enemy combatants who are non-U.S. citizens, including permanent resident aliens, if the United States Attorney General certifies that he has “reasonable grounds to believe” that the non-citizen has engaged in terrorist activity.