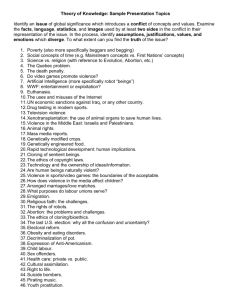

Family Violence and Youth Justice Project Workshop Toolkit

advertisement