**aorO H D**********`***U******* ****x* **X6)**" +(.P( Q@\@* dQ

advertisement

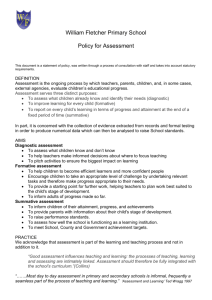

Assessment Pedagogy and the Teachers’ Role Paul Black Department of Education King’s College London 1 Validity in the future? … the teacher is increasingly being seen as the primary assessor in the most important aspects of assessment. The broadening of assessment is based on a view that there are aspects of learning that are important but cannot be adequately assessed by formal external tests. These aspects require human judgment to integrate the many elements of performance behaviours that are required in dealing with authentic assessment tasks. • p.31 in Stanley, G., MacCann, R., Gardner, J., Reynolds, L. & Wild, I. (2009). Review of teacher assessment: what works best and issues for development. Oxford University 2 Centre for Educational Development; Report commissioned by the QCA. Thomas Groome Educating for Life (Children) . . have a right to a curriculum that convinces them of their inherent goodness, that convinces them of their dignity and self-worth, that treats them with respect, that helps to develop their every good gift and talent 3 Hargreaves The Knowledge Creating School . . . .. . schools must prepare students to increasingly higher levels of knowledge and skill, not just in the conventional curriculum or even in ICT, important as these are, but also in the personal qualities that matter in the transformed work place – how to be autonomous, self-organising, networking, entrepreneurial, innovative, with ‘the capability constantly to redefine the necessary skills for a given task, and to access the sources for learning these skills’ . 4 Hargreaves The Knowledge Creating School It is plain that if teachers do not acquire and display this capacity to re-define their skills for the task of teaching, and if they do not model in their own conduct the very qualities – flexibility, networking, creativity – that are now key outcomes for students, then the challenge of schooling in the next millennium will not be met. (p.123) 5 Can Summative Assessment be Improved? Where summative becomes the hand-maiden of accountability matters can get even worse, for accountability is always in danger of ignoring its effects on learning and thereby of undermining the very aim of improving schooling that it claims to serve. Accountability can only avoid shooting itself in the foot if, in the priorities of assessment design, it comes after learning 6 Black & Wiliam 2007 Integrating Assessment Within Pedagogy •1 Deep Contradictions •2 AiFL – the promise of harmony •3 Summative: Redemption via Teacher Ownership •4 Systems, Support and Development 7 1 Dialogic Teaching Children, we now know, need to talk, and to experience a rich diet of spoken language, in order to think and to learn. Reading, writing and number may be acknowledged curriculum ‘basics’, but talk is arguably the true foundation of learning. (Robin Alexander, 2004) 8 Pupil involvement •When a question is asked or a problem posed who is thinking of the answer? Is anybody thinking about the problem apart from the teacher? How many pupils are actively engaged in thinking about the problem? Is it just a few well motivated pupils, or worse is it just the one the teacher picks out to answer the question? The pupil whose initial reaction is like that of a startled rabbit ‘Who me sir?’ (Teacher in King’s Project) 9 Poverty of Classroom Dialogue • Average ‘wait time’ 0.9 seconds (Rowe, 1974, USA) • Open questions – 10% only. 15% of teachers did not use any. Follow-up questions only 4%of the time; 43% of teachers did not use any. Pupil contributions – 3 words or fewer for 70% of the time (Smith et al. 2004, U.K.) • Teacher Qn - Pupil answer – Teacher Qn and so on. “Recitation” dominates (Applebee et al. 2003, USA) 10 Dialogic Teaching Talk vitally mediates the cognitive and cultural spaces between adult and child, among children themselves, between teacher and learner, between society and the individual, between what the child knows and understands and what he or she has yet to know and understand. (Alexander, 2008, p.92) 11 The school and society Once children move from the intimacies of family life into the impersonality and organization associated with life in classrooms, they cannot help becoming subject to the prevailing ideology, to socialization in its varying forms. The norms communicated by the hidden curriculum – because unacknowledged, often more powerful than what is explicitly taught – are in conflict with the values publicly affirmed. (Greene, 1983) 12 2 Do we need to have marks on everything ? Students are not good at knowing how much they are learning, often because we as teachers do not tell them in an appropriate way ........................................................... When asked by a visitor how well she was doing in science, the student clearly stated that the comments in her exercise book and those given verbally provide her with the information she needs. Teacher in King’s project 13 Feedback on Written Work Comment-only marking Previously I would have marked the work and graded it and made a comment. The pupils only saw the mark and/or credit. After a credit they lost the motive to improve. Now they get a credit after we have gone over the work so they have an incentive to understand the work Teacher in King’s project. 14 3 Advantages of Peer Assessment All pupils can be involved They use pupil language - and start to talk the language of the subject They are more honest and challenging with one another than with their teacher Seeing your work through the eyes of your peers helps you to be more objective Teachers can spot where they might best spend their time BUT Pupils need to be trained to work effectively in groups 15 Rules for Effective Group Work • All students must contribute: no one member say too much or too little • Every contribution treated with respect: listen thoughtfully • Group must achieve consensus: work at resolving differences • Every suggestion/assertion has to be justified: arguments must include reasons Mercer, N., Dawes, L., Wegerif, R. and Sams, C. (2004) British Educational Research Journal, 16 30(3), 359-377. Pupils’ Perspective After each end of term test, the class is grouped now to learn from each other. [The researcher] has interviewed them on this experience and they are very positive about the effects. Some of their comments show that they are starting to value the learning process more highly and they appreciate the fact that misunderstandings are given time to be resolved, either in groups or by me. They feel that the pressure to succeed in tests is being replaced by the need to understand the work that has been covered and the test is just an assessment along the way of what needs more work and what seems to be fine Teacher in King’s project 17 Carol Dweck Mindset I’ve seen so many people with one consuming goal of proving themselves – in the classroom, in their careers, and in their relationships. Every situation calls for a confirmation of their intelligence, personality or character. Every situation is evaluated: Will I succeed or fail? Will I look smart or dumb? Will I be accepted or rejected? Will I feel like a winner or a loser? There’s another mindset . . . . . . This growth mindset is based on the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your own efforts. 18 Integrating Assessment Within Pedagogy •1 Deep Contradictions •2 AiFL – the promise of harmony •3 Summative: Redemption via Teacher Ownership •4 Systems, Support and Development 19 Assessment in Pedagogy •A Decide learning aims •B Select and plan activities •C Implement in classroom •D Review: informal summative assessment •E Formal summative assessment 20 Developing teachers’ summative assessments Decisions about teaching sets Information for the next teacher Reporting to Senior Management Team Reporting to Parents Guiding the pupil Black, P., Harrison, C., Hodgen, J., Marshall, M. & Serret, N. (2010) Validity in teachers’ summative assessments. Assessment in Education 17(2) 215-232 21 Present Practice Unfortunately, teachers often develop a set of classroom routines with little opportunity to examine and reflect on their concepts of classroom assessment and how this informs their decisions about the selection and design of questions and tasks, how they interpret student responses, and how to respond to students through instruction and feedback. Webb (2009) p.11 – USA 22 Validity What does it mean to be good at - - The project made me think more critically about what exactly I was assessing. The first question I remember being asked (‘what does it mean to be good at English?’) gave me a different perspective on assessment. I find myself continually returning to this question. Teacher in King’s project 23 How valid is this evidence ? What do formal tests tell us? •The ability to produce from memory, without access to any resources. • Within a few hours in the exam. room. • Written accounts of a few topics. • Selected from up to 5 years of study. • In a high-stress situation. • When one’s future opportunities depend on the outcome. 24 Evidence Classroom Tasks • Compare different newspapers (e.g., tabloid, broadsheet, local) by generating and investigating a hypothesis using simple descriptive statistics. • “Falling” : after reading the story of Icarus, produce a spectator’s description of the event. • Dissolving: Devise and use a method to find out whether more salt will dissolve in vinegar than in water 25 Evidence Teachers’ Design of Tasks Implementation of tasks – staff were a bit reluctant to do the projects, . . . but post projects their views changed and this year development of investigation based tasks has become an issue that the KS3 staff have been keen to do and is being done as part of performance management. (Teacher in King’s project) 26 Steps in Development of Teachers’ Summative Assessments 1 Audit 2 Validity 3 Evidence Design of tasks Pupil portfolios 4 Dependability and comparability Agreed criteria Moderation – in and between schools 27 Moderation: teaching and learning conversations I think its quite a healthy thing for a department to be doing because I think it will encourage people to have conversations and it’s about teaching and learning. . . . it really provides a discussion hopefully as well to talk about quality and you know what you think of was a success in English. Still really fundamental conversations. Teacher in King’s project 28 Moderation: shared agreement about standards . . . the introduction of standards requires primary teachers and schools to investigate the meaning of the work that students generate. Whilst teachers have always made judgments informally, moderation as an organised process requires making collaborative decisions to reach consensus agreements, and hence has become an important professional responsibility for all New Zealand’s primary school teachers. New Zealand (Hipkins and Robertson 2011 p.5) 29 Moderation: linking aims to questions Furthermore, as teachers adapted practices, they began to re-think the learning objectives of their curricula and the questions they used during instructional activities. USA (Webb, 2009, p.14) 30 Moderation: Aims, Questions and Pedagogy So basically once you have the assessment firmly in place the pedagogy becomes really clear because your pedagogy has to support that – that sort of quality assessment task . . . . that was a bit of a shift from what’s usually done, usually assessment is that thing that you attach on the end of the unit whereas as opposed to sort of being the driver which it has now become. Wyatt-Smith and Bridges (2008) p.48 – Queensland 31 Moderation: Collaborative Professional Development Similarly, teachers who examined student data together and worked out as a group what its implications were for deciding how best to help those under-achieving, difficult-to-move students, had higher achieving students than those schools where such a collective examination, diagnosis and problem-solving cycle did not operate. New Zealand : Parr and Timperley, 2008, p.69 32 Moderation: sharing criteria with students . . . . I think to a certain extent that we’ve empowered students in the learning process because there’s not secret teacher’s business anymore in terms of what the expectations are, that students are becoming very au fait with the criterion and being able to apply them in their own work. Australia (Wyatt-Smith & Bridges 2008, p.61) 33 Assessment in Pedagogy •A Decide learning aims •B Select and plan activities •C Implement in classroom •D Review: informal summative assessment •E Formal summative assessment 34 Validity in the future? … the teacher is increasingly being seen as the primary assessor in the most important aspects of assessment. The broadening of assessment is based on a view that there are aspects of learning that are important but cannot be adequately assessed by formal external tests. These aspects require human judgment to integrate the many elements of performance behaviours that are required in dealing with authentic assessment tasks. • p.31 in Stanley, G., MacCann, R., Gardner, J., Reynolds, L. & Wild, I. (2009). Review of teacher assessment: what works best and issues for development. Oxford University 35 Centre for Educational Development; Report commissioned by the QCA. Assessment in Pedagogy • Validity – more occasions, more contexts, greater range of types of activity • Teachers can share criteria with pupils – who own their individual portfolios • Teachers develop confidence in their skills in assessment • Teachers learn through the need to collaborate. • Teachers judgments become trustworthy • Status of the profession is enhanced • Assessment embedded within learning 36 Integrating Assessment Within Pedagogy •1 Deep Contradictions •2 AiFL – the promise of harmony •3 Summative: Redemption via Teacher Ownership •4 Systems, Support and Development 37 Involving Teachers as Agents in Development Any change to assessment processes (or in fact any educational reform) hinges on support from teachers, and support for teachers, to ensure an ability to adapt at classroom level. . . . . . This requires theoretically-based yet practically-situated learning rather that decontextualised one-shot professional development. (Gunn 2007, p.59) 38