Scottsboro Newspaper Article

advertisement

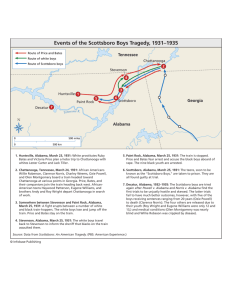

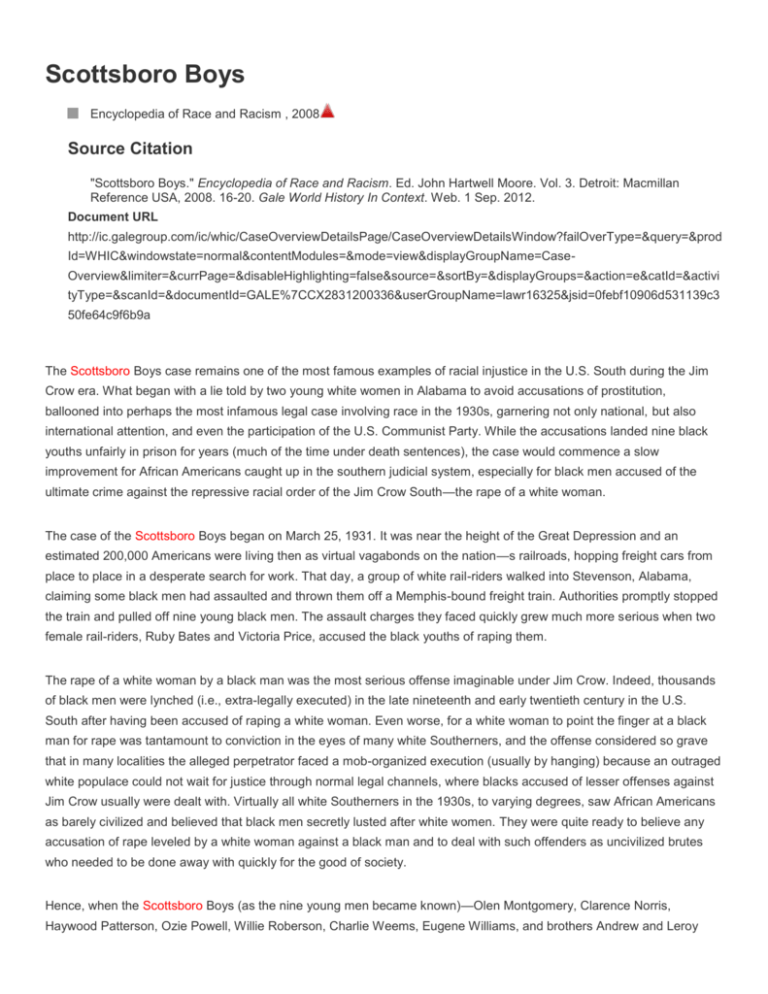

Scottsboro Boys Encyclopedia of Race and Racism , 2008 Source Citation "Scottsboro Boys." Encyclopedia of Race and Racism. Ed. John Hartwell Moore. Vol. 3. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008. 16-20. Gale World History In Context. Web. 1 Sep. 2012. Document URL http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/whic/CaseOverviewDetailsPage/CaseOverviewDetailsWindow?failOverType=&query=&prod Id=WHIC&windowstate=normal&contentModules=&mode=view&displayGroupName=CaseOverview&limiter=&currPage=&disableHighlighting=false&source=&sortBy=&displayGroups=&action=e&catId=&activi tyType=&scanId=&documentId=GALE%7CCX2831200336&userGroupName=lawr16325&jsid=0febf10906d531139c3 50fe64c9f6b9a The Scottsboro Boys case remains one of the most famous examples of racial injustice in the U.S. South during the Jim Crow era. What began with a lie told by two young white women in Alabama to avoid accusations of prostitution, ballooned into perhaps the most infamous legal case involving race in the 1930s, garnering not only national, but also international attention, and even the participation of the U.S. Communist Party. While the accusations landed nine black youths unfairly in prison for years (much of the time under death sentences), the case would commence a slow improvement for African Americans caught up in the southern judicial system, especially for black men accused of the ultimate crime against the repressive racial order of the Jim Crow South—the rape of a white woman. The case of the Scottsboro Boys began on March 25, 1931. It was near the height of the Great Depression and an estimated 200,000 Americans were living then as virtual vagabonds on the nation—s railroads, hopping freight cars from place to place in a desperate search for work. That day, a group of white rail-riders walked into Stevenson, Alabama, claiming some black men had assaulted and thrown them off a Memphis-bound freight train. Authorities promptly stopped the train and pulled off nine young black men. The assault charges they faced quickly grew much more serious when two female rail-riders, Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, accused the black youths of raping them. The rape of a white woman by a black man was the most serious offense imaginable under Jim Crow. Indeed, thousands of black men were lynched (i.e., extra-legally executed) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in the U.S. South after having been accused of raping a white woman. Even worse, for a white woman to point the finger at a black man for rape was tantamount to conviction in the eyes of many white Southerners, and the offense considered so grave that in many localities the alleged perpetrator faced a mob-organized execution (usually by hanging) because an outraged white populace could not wait for justice through normal legal channels, where blacks accused of lesser offenses against Jim Crow usually were dealt with. Virtually all white Southerners in the 1930s, to varying degrees, saw African Americans as barely civilized and believed that black men secretly lusted after white women. They were quite ready to believe any accusation of rape leveled by a white woman against a black man and to deal with such offenders as uncivilized brutes who needed to be done away with quickly for the good of society. Hence, when the Scottsboro Boys (as the nine young men became known)—Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Haywood Patterson, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Charlie Weems, Eugene Williams, and brothers Andrew and Leroy (Roy) Wright—were taken to Scottsboro, the seat of Jackson County, in far northeastern Alabama, for incarceration and trial, many white Southerners congratulated themselves for what they saw as a moderate, even enlightened response to the gravest of crimes. (Although Alabama governor Benjamin Meeks Miller, afraid of a lynching, still felt it necessary to guarantee the safety of the prisoners by sending 119 armed National Guardsmen to Scottsboro). If Alabama and the white South felt pride at their restrained reaction to the accusations of gang rape of white women by black men, they squandered whatever goodwill garnered outside the region in the initial trials of the Scottsboro Boys. These proceedings were a travesty of justice. They took place in a carnival atmosphere that emphasized rather than concealed the white populace’s furious mood, its anger stirred by wildly inflated rumors about the alleged rape. Given their race, poverty, and the horrific nature of the alleged crime, it proved impossible for the Scottsboro Boys to secure competent legal representation. They were forced to go on trial represented by Stephen R. Roddy, an alcoholic lawyer hired with money raised by leading black citizens in nearby Chattanooga, Tennessee. With inadequate representation and having already been convicted in the media, the outcome of the nine boys’ trial was a foregone conclusion. Each of the Scottsboro Boys was quickly convicted by all-white juries and sentenced to death, except for thirteen-year-old Roy Wright whose jury could not unanimously decide on a death sentence due to his youth and whose case was declared a mistrial. With the circumstances of the trials widely reported throughout the United States and abroad, outrage quickly developed outside the South against the verdicts and death sentences levied on the Scottsboro Boys. While many observers expected that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) would step in to fund and manage the youths’ appeals, the U.S. Communist Party, through its front organization, International Labor Defense (ILD), moved quicker to gain the allegiance of the nine men and their families. With the Great Depression causing many Americans to question the future of capitalism as they never had before, the Communists historically were at the peak of their popularity in the United States, and saw the Scottsboro case as a way to make inroads among African Americans both in the South and elsewhere. As perhaps the only political organization of that era to practice as well as preach racial equality, the Communists were hopeful the case would garner mass support among black Americans and hasten what they believed would be the inevitable revolution of the working class against capitalism in the United States. The speed with which the ILD took over the Scottsboro Boys’ defense stunned the NAACP, which was initially reluctant to involve itself in the case until convinced of the nine young men’s innocence. Its efforts to replace the Communists ignited a fight for control that would continue, off and on, for four years. The battle pitted the NAACP’s relatively greater resources and respectability against the ILD’s ideological fervor and ruthless determination. For example, the Communists made small payments to the families of the Scottsboro Boys and took some of their mothers on speaking tours to the North and abroad as a way of cementing the youths’ allegiance. They would later go so far as to try and bribe Victoria Price to recant her original accusation. The fallout of such disasters and their lack of resources would force the ILD in late 1935 to join forces with the NAACP, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and other more moderate groups into the “Scottsboro Defense Committee.” Nonetheless, the Communist Party through the ILD would take the lead role in organizing and funding the defense of the Scottsboro Boys in its early years. ILD initially hired George W. Chamlee, a maverick Chattanooga attorney with a history of defending leftist radicals in the South, as the new defense counsel for the Scottsboro Boys. They felt the case needed a white Southerner who would have credibility with the Alabama Supreme Court. Chamlee based his appeal there on the inadequate counsel of Stephen R. Roddy in the original trial. While Chamlee’s argument before the Alabama Supreme Court failed, it was a necessary step on the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the justices agreed to hear the case, Powell v. Alabama, and in November 1932 overturned the conviction of the Scottsboro Boys on the grounds of inadequate representation in the original trial. The victory in the U.S. Supreme Court sent the case back to Alabama for retrial. Given the case’s high profile, the Communists were able to retain for the Scottsboro Boys one of the best lawyers available: Samuel Leibowitz, a New Yorker and Romanian-born Jew, considered by many observers, after the retirement of Clarence Darrow, to be the finest criminal defense attorney in the United States. In fifteen years as a practicing criminal attorney, Leibowitz had not yet had a client convicted. Leibowitz took the case pro bono on the condition that he would work independently of ILD, whose role would be limited to fundraising and generating public support for Scottsboro Boys (a limitation the Communists were illprepared to accept in practice and one that would inevitably lead to repeated clashes with Leibowitz). Despite his mounting a first-class defense for his nine clients during the second round of trials in March 1933, Samuel Leibowitz’s logic and eloquence were insufficient in the face of white southern prejudice. Although the defense was able to obtain a change of venue in the second trial from Scottsboro to Decatur, Alabama (fifty miles to the west), they were still dealing with all-white juries imbued with the Jim Crow system. Indeed, Leibowitz’s attempts to discredit Victoria Price as a witness backfired because the Decatur jury, instead of seeing the clear problems with her account, was instead gravely offended that a New York Jew would dare question a white southern women’s assertion that she had been raped by African Americans. Despite the fact that Ruby Bates, Price’s co-complainant, recanted her accusations at the second trial and the medical testimony clearly indicated no rape had ever occurred, the jury that decided the fate of the first Scottsboro defendant who was re-tried, Haywood Patterson, quickly convicted him and fixed his sentence again at death. Surprisingly, while Leibowitz had offended the Patterson jury, he had convinced the judge that presided over the Decatur retrial, James Horton, of the Scottsboro Boys’ innocence. The first sign of Horton’s sentiments came after Patterson’s conviction. The judge suspended further proceedings for the other eight defendants because the inflamed public sentiments evident after the Patterson’s conviction would clearly prevent them from getting a fair trial. After a three-month delay, Judge Horton granted a defense motion in June 1933 that Patterson receive a new trial. His sentiments reflected the opinion among a small but growing group of moderate whites in Alabama that were willing to entertain the notion the Scottsboro Boys might be innocent or at least did not deserve the death penalty. Yet the vast majority of white Alabamians remained firmly convinced of the need to convict and execute the nine defendants, and made persons with more moderate opinions pay a price if they exhibited them too publicly. For example, Horton failed to retain his judgeship when he came up for reelection in 1934. The third round of trials, which began in November 1933, reflected the will of most whites in Alabama to press the proceedings toward the conviction and execution of the Scottsboro Boys, whatever it took. Leading the effort to continue the prosecution was Alabama’s attorney general, Thomas G. Knight, who had been a central figure in the case since he had argued his state’s case before the U.S. Supreme Court in Powell v. Alabama. Knight led the prosecution team personally in Haywood Patterson’s retrial and in the third round of trials. He found an ally in William Washington Callahan, the judge who took over the case when proceedings resumed on November 20, 1933, in Decatur, Alabama. Callahan rejected Leibowitz’s motions for a change of venue and his efforts to challenge the exclusion of African Americans from the jury pool in Morgan County, Alabama. He also placed severe restrictions on Leibowitz’s ability to question Price on her activities prior to the alleged rape, tantamount to blocking the lawyer’s ability to cross-examine her adequately. Callahan also frequently added his own objections to those of Knight, and his instructions to the jury essentially served as a second summation for the prosecution. The judge also tried to use the post-trial procedures to create technicalities to deny Leibowitz’s ability to appeal the guilty verdict and Patterson’s third death sentence. In any case, the Alabama Supreme Court rejected Leibowitz’s appeal on behalf of Patterson, and the case once again went before the U.S. Supreme Court. The appeal was complicated not only by the procedural roadblock created by Judge Callahan, but also because at this time the attempt of ILD to bribe Price became public. The revelation led to a temporary break in relations between Leibowitz and the ILD, which were repaired in time for the oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court in February 1935. Unlike before, the Scottsboro Boys’ second appeal to the nation’s highest court was based on the exclusion of African Americans from the jury pool in Decatur, Alabama. Leibowitz had carefully made an issue of this practice during jury selection in the trials there. His argument before the justices was bolstered by clear evidence that someone had amateurishly inserted names of potential black jurors to the juror rolls before the Decatur trials presided over by Judge Callahan in an attempt to conceal the longstanding exclusion of African Americans from juries there. Although the Supreme Court refused to make new case law in its decision of the second appeal, it remanded the case back to the Alabama Supreme Court with the clear implication that if the Alabama justices did not order a new trial, it would review the case again. (The Alabama Supreme Court complied.) Yet the second victory of the Scottsboro Boys in the U.S. Supreme Court did not soften the opinions of most white people in Alabama. As the premier historian of the Scottsboro case, Dan T. Carter, stated of white Alabamians, The majority … had adopted the position that mass electrocution was necessary in order to insure the ‘social stability of this section,’ observed John Temple Graves, II. It was the ‘inflexible if misguided conviction of many Alabamians … that [even after three rounds of trials] a fresh start be made in the business of getting the accused men to the electric chair’.’’ (Carter 1979, pp. 328–29) Hence, a fourth round of trials began in Decatur, Alabama, in January 1936, with Patterson going first. Leibowitz, although still chief counsel for the defense, was not as prominent as in the earlier trials because he had by this time become a hated figure among white Alabamians for his uncompromising courtroom style, especially his firm cross-examinations of Price, and the fact he was a New York Jew, something that had been politely overlooked prior to his assault on southern womanhood. Judge Callahan remained in charge and continued making his own objections to questions posed by the defense and generally making no secret of his contempt for them. Yet Patterson’s 1936 trial proved something of a breakthrough: when after his inevitable conviction, the jury, rather than sentencing him to death, set down his punishment as imprisonment for seventy-five years. The prison sentence for Patterson demonstrated that as committed as conservative whites in Alabama were to the conviction and execution of all of the Scottsboro Boys to preserve white supremacy, a more moderate and pragmatic element in the state was willing to engineer a face-saving compromise to end the judicial proceedings once and for all. The negotiations of the compromise remain unclear, but the basic terms quickly took shape. First, prosecution would be dropped against those defendants with the weakest cases against them in terms of their alleged culpability for the assault on the white rail-riders. Second, the convictions against the remaining defendants would stand, but they would be not be sentenced to death and eventually would be pardoned and set free. Furthering the atmosphere for compromise was the sudden death, in July 1937, of Thomas G. Knight. Knight had tied his political career to convicting the Scottsboro Boys, and had even continued to lead the prosecution team after his election as Alabama’s lieutenant governor in November 1934. While many white Alabamians, Judge Callahan in particular, wanted to continue with the prosecution of all the Scottsboro Boys for rape, Knight’s death removed their most effective advocate. In other words, Knight’s death apparently made possible what became known as the “Compromise of 1937.” Despite the fact that Clarence Norris went on trial again for his life on July 12, 1937, and despite the fact he was again convicted and sentenced to death, rumors that a grand bargain involving all the Scottsboro Boys was in the making circulated in the press. These rumors continued even when Charlie Weems was convicted of rape in his 1937 trial and sentenced to seventy-five years, as had been the case with Patterson. They took on reality when Ozie Powell was brought to court for his trial, and Judge Callahan informed him the rape charges against him had been dropped and he would instead be prosecuted for assaulting a deputy sheriff (an incident that had occurred during Patterson’s last trial). Powell pled guilty to the assault charge and Callahan sentenced him to twenty years. Charges were then quickly dropped against Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams, and Roy Wright. These four men were quickly whisked by Leibowitz out of Alabama to New York City, where they received a hero’s welcome, but then quickly slipped into obscurity (and in some cases continued to live troubled lives). The pardons for the remaining Scottsboro defendants still in prison were slow in coming. Governor Bibb Graves of Alabama refused quick pardons, but he did commute the death sentence of Clarence Norris to life imprisonment. Evidently, Graves believed that if he released the remaining Scottsboro Boys it would be the end of his political career. As the U.S. Supreme Court refused further appeals and President Franklin Roosevelt declined to exert more than gentle pressure on Graves, the five men left in prison remained incarcerated for years. It would take a world war and fading memories for freedom to become possible for them. Having finally entered the Alabama corrections system, their cases came under the control of the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles. It apparently opted for a policy of gradually releasing without fanfare the remaining Scottsboro Boys. The first to bet set free was Charley Weems in November 1943. In January 1944, it paroled Andrew Wright and Clarence Norris. The two men fled the state, in violation of their paroles, were persuaded to return and were reimprisoned. This episode put a temporary stop to the releases until near the end of 1946, when the board released Powell and re-paroled Norris. Patterson, considered by his jailers the most incorrigible of the Scottsboro Boys, escaped from a work detail in 1948 and successfully eluded recapture, making his way to Michigan, where he permanently gained freedom because the governor of the state refused to extradite him. In 1950, when Wright was re-paroled, the last of the men arrested in 1931 finally went free for good. They, like their compatriots freed in 1937, also faded into obscurity. Clearly, the resolution of the Scottsboro case was designed in the end for the racist Alabama justice system to save face. Yet it also signaled to the white South that, unlike in the past, people outside the region were watching, not only in the rest of the United States but abroad as well. While racist injustice did not end overnight, change was in the wind, and the Scottsboro Boys helped demonstrate by the 1970s just how much the southern justice system had changed. After NBC in 1976 showed a made-for-television docudrama on the Scottsboro case, Norris, apparently the last surviving Scottsboro Boy, resurfaced asking for a full and unconditional pardon. Alabama governor George Wallace readily gave this pardon. Granted by a politician who had initially made his career as a segregationist but experienced a change of heart, it was a fitting bookend to the case since a “full and unconditional” pardon was generally reserved for those cases where the state recognized the original prosecution and conviction itself had been erroneous. BIBLIOGRAPHY Carter, Dan T. 1979. Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South, rev. ed. Baton Rogue: Louisiana State University Press. Chalmers, Allan Knight. 1951. They Shall Be Free. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. Goodman, James. 1994. Stories of Scottsboro. New York: Pantheon. Kinshasa, Kwando Mbiassi. 1997. The Man from Scottsboro:Clarence Norris and the Infamous 1931 Alabama Rape Trial in His Own Words. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. Miller, James A., Susan D. Pennybacker, and Eve Rosenhaft. 2001. “Mother Ada Wright and the International Campaign to Free the Scottsboro Boys. ” American Historical Review 106 (April): 387–430. Norris, Clarence, and Sybil D. Washington. 1979. The Last of the Scottsboro Boys: An Autobiography. New York: G. P. Putnam. Patterson, Haywood, and Earl Conrad. 1950. Scottsboro Boy. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. Donald R. Shaffer http://callisto.ggsr en Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2009 Macmillan Reference USA, a part of Gale, Cengage Learning.