Growth Impacts 7WK

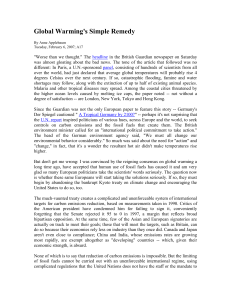

advertisement