A5_A017 Brand Extension-The Assessment of Perceived Brand

advertisement

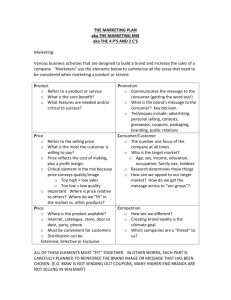

Brand Extension: The Assessment of Perceived Brand Extension Fit in the Education Context Damrong Sattayawaksakul, Sokcheng Ung, Kraiwin Jongsuksathaporn, Tran Tien Dat About the author Damrong Sattayawaksakul is the Dean of the Faculty of Business Administration at AsiaPacific International University. Sokcheng Ung is a student in the Faculty of Business Administration at Asia-Pacific International University. Kraiwin Jongsuksathaporn is a student in the Faculty of Business Administration at AsiaPacific International University. Tran Tien Dat is a student in the Faculty of Business Administration at Asia-Pacific International University. Abstract The authors develop a conceptual model of factors that determine perceived brand fit in the brand extension context. The study examines the relationship of brand image consistency, product feature similarity, and brand extension authenticity to perceived brand extension fit. The study conducted among 100 students, which examine an extension of education brand into a water bottle product. Structural equation modeling serves to test the hypotheses. The study reveals that perceived brand extension fit can be leveraged from the brand image consistency, product feature similarity, and brand extension authenticity. Keywords: Brand extension, Brand image consistency, product feature similarity, brand extension authenticity, perceived brand extension fit Introduction A brand is a set of perceptions and images that represent a company, product or service (Persuade brands, 2013). While many people refer to a brand as a logo, name, or symbol, a brand is actually much broader. A brand is the essence or promise of what will be delivered or experienced. Importantly, brands enable a buyer to easily identify identifies one seller's product distinct from those of other sellers. Brands are generally developed over time through marketing strategies. Once developed, brands provide an umbrella under which many different products can be offered. Recognition of the value of brands has lead marketers to seek ways to leverage brands to increase their value through brand extension. Marketers use this brand strategy in attempting to transfer the positive associations of the parent brand to the extended product. Brand extension strategy consists of placing a well-known brand name on a new product line or new market segment. According to D. A. Aaker and Keller (1990), brand extension provides a way to take advantage of brand awareness and brand image to enter new markets. The well developed strong brand can greatly reduce the risk of introducing new products on the market by providing consumers with the knowledge and awareness. In addition, the brand can reduce the cost of distribution to increase the effectiveness of promotional spending. While there may be benefits in extending the brand, there can also be a significant risk to brand image dilution. Poor choice for a brand extension may dilute and weaken the core brand and brand equity. Even though many of the business 1 operations have been practicing brand extension strategy to extend their brands and products for many years, there is limited academic investigation on the nature of the strategy. Most of the previous researches in brand extension based their investigation on customer attitude. They addressed two broad areas: how customers’ perceptions of a extended product are influenced by their perceptions on the parent brand; the performance comparison between brand extension and other new product development strategies (Leuthesser, Kohli, & Suri, 2003). The prior research has found that perceived fit between original category and the brand extension serves as an important antecedent of consumer brand extension evaluations (Batra, Lenk, & Wedel, 2010; Lau & Phau, 2007; Phau & Lau, 2001; Yorkston, Nunes, & Matta, 2010). However, few examine any details concerning the nature of brand fit. This study aims to explore components and factors of brand fit. The results of this study would expand the limited knowledge of the nature of brand fit in brand extension, especially in the context of education brand in Thailand. The results of this study would also offers guidance for the practitioners to understand the nature of fit in applying various brand extension strategies. Objectives of Research There are three main objectives of this study. First, this study aims to examine the specific components and factors of brand fit under the brand extension strategy. Second, the study aim to examine how the fundamental components and factors of brand fit under the brand extension strategy interact/relate to each other. Finally, the study also investigate the phenomenal of brand fit under the brand extension strategy in the context of education brand in Thailand Theoretical Background Brand Extension Brand extension is defined as placing a well-known brand name on a new product line or new market segment (e.g., kitchen appliance maker extending to home laundry appliances). J. L. Aaker (1997) points out that brand extension can be distinguished by direction as vertical or horizontal. Vertical extensions involve introducing a related brand in the same product category but with a different price and quality balance. In contrast, horizontal brand extensions either apply or extend an existing product’s name to a new product in the same product class or to a product category new to the company. One of the most obvious differences is whether the extension is in the same or different product category. On the other hand, Farquhar (1989) and Keller (2003) present two approaches for brand extension: category extension and line extension. Category extension involves the use of an established brand name to enter a completely different product category. While, line extension involves the use of an established brand name to enter a new market segment in the same product category. Combining both J. L. Aaker (1997) and Keller (2003) of brand extensions results in a matrix with four different forms of brand extensions, as presented in Table 1: vertical line extension; vertical category extension; horizontal line extension; and horizontal category extension. Table 1 Forms of Brand Extension: Combination of Aaker and Keller approaches Type/Direction Line extension Category extension Vertical Vertical line extension Horizontal Horizontal line extension Horizontal category extension 2 Vertical category extension A number of factors have been proposed to influence consumers' acceptance of extensions. Much focus has been on how extension judgments might be shaped by the perceived quality of the original brand. There is ample empirical evidence that strong quality brands benefit extensions more than weak brands (e.g.(D. A. Aaker & Keller, 1990; C. W. Park, Milberg, & Lawson, 1991; J.-W. Park, Kim, & Kim, 2002; Smith & Park, 1992). Another important factor considered in the literature is the category similarity between an extension and the original brand. It has been shown that an extension of a strong brand tends to be evaluated more favorably when the extended category is similar to the original brand category. When consumers perceive a lack of category fit, the extension is doomed to fail (D. A. Aaker, and Keller, K., L., 1992). Cognitive categorization theory Cognitive categorization theory suggests that humans have a tendency to label object (product or brand) with descriptive words and phrases (first impression). Label objects as soon as you aware of them (high quality, bad, good, etc). People can't remember much about object (product or brand) besides how they were labeled (categorized). These labels are extremely resistant to change. Grouping items into categories is important because it can influence individuals’ judgments and decisions (Brough & Chernev, 2012). For example, categorization has been shown to affect consumers’ choices, perceptions of assortment variety, and satisfaction. Perceived Brand Extension Fit Several brand extension researchers have tried to identify the factors that define successful brand extensions. They have viewed the fit between a parent brand and the extension category as a determinant of the success of the extension (D. A. Aaker & Keller, 1990). Perceived brand fit is the similarity or feature overlap between the parent brand and extension category (D. A. Aaker & Keller, 1990). Two perspectives on fit: similarity; and relevance, coexists in brand extension literature. Both perspectives rely on cognitive categorization theory, which assumes that brands are cognitive categories formed by a network of associations organized in people’s memory. The associations may be based on shared product features, attributes, benefits, or other common linkages, such as user imagery, and perceived brand extension authenticity (D. A. Aaker & Keller, 1990; Spiggle, Nguyen, & Caravella, 2012). Hypotheses and Conceptual Model Brand Image Consistency and Brand Extension Authenticity C. W. Park et al. (1991) examined the role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency that differentiate between successful and unsuccessful brand extensions. The results reveal that brand extension will be successful when having a parent brand with an image that is compatible with the extension. Furthermore, they found that consumers are aware of the differences between function-oriented and prestige-oriented concepts. For both function-oriented and prestige-oriented brand names, the most favorable reactions take place when brand extensions are made with high brand concept consistency and high product feature similarity (C. W. Park et al., 1991). In addition, these two factors cause different impact to brand extension depending on the type of parent brand. For prestige-brands, extensions must be clearly related to the values and concept of the company. Concept consistency seems to be the major key to brand extensions for prestige brands. For functional brands, because of the difficulty of identifying the brand concept, product feature similarity is relatively more important since common features of a functional brand’s products are easier to be recognized by consumers. Simonin and Ruth (1998) adopted Aaker and Keller 3 dimensions of perceived fit to evaluate brand alliance (one of the forms of brand extension). They found a collaborative relationship also involves the brand images of each parent brands. If the two brand images are perceived fit, the co-branded product will be evaluated more favorably compared to the inconsistent or incompatible brand image. Brand image consistency could be defined as perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory (Keller, 1993). Spiggle et al. (2012) developed the construct and scale items based on the authenticity and the brand extension literatures. They conducted four empirical studies where two of them are particularly examine the distinction and the relationship between brand extension authenticity and brand fit. Based on the second study which examined the prediction power of brand extension authenticity relative to brand fit through 236, the results showed that brand image relates to brand fit through some component of brand extension authenticity. Thus, we hypothesised that: H1: Brand image consistency relates positively to brand extension authenticity. Product Feature Similarity and Brand Extension Authenticity Product feature similarity is defined as the similarity of extension product/service feature or outlook (e.g. color, building style, service style). Several researchers investigate the product purchasing intension. Helmig, Huber, and Leeflang (2007) studied the phenomenal and found product fit and brand fit influence the consumer evaluation of co-branded products. The arguments are in line with Dickinson and Heath (2006). They adopted both D. A. Aaker and Keller (1990) and C. W. Park et al. (1991) dimensions of perceived fit to investigate brand extension strategy. They collected both qualitative and quantitative data regarding 12 experimental extension products from 194 university students in Australia. The results show that perceived fit between parent brands, based on product category or brand concept consistency, is positive related to brand extension evaluation. Thus, we hypothesised that: H2: Product feature similarity relates positively to brand extension authenticity. Brand Extension Authenticity and Perceived Brand Extension Fit Consumer evaluation on the relationship of brand extensions and perceived fit with the parent brand is one of the most enduring findings from branding research (Kim & John, 2008). Prior researchers identified perceived fit is the most important factor determined brand extension success. Among others, D. A. Aaker and Keller (1990) suggested perceived fit consists of three dimensions: complementarity; transferability; and substitutability. They conducted two studies to investigate on how consumers form attitudes toward brand extensions. In the first study, they evaluated consumer perceptions on brand fit and brand extension through a set of six actual brands and 20 hypothetical brand extensions from 107 undergraduate students. The results show that attitude toward the extension was higher when there was a perception of fit, and specifically, the relationship of an image for the parent brand with the evaluation of a brand extension was strong only when there was a basis of fit between the parent brands. On the other hand, authenticity is becoming an important business concept today. Authenticity is accepted by both academia and marketers as a core component of successful brands because it forms part of a unique brand identity that constitutes in brand equity (Beverland, 2005; Keller, 1993). Brand Extension Authenticity could be define as a consumer’s sense that a brand extension is a legitimate, culturally consistent extension of the parent brand. Spiggle et al. (2012) argue that the authenticity of a brand extension relative to the parent brand also affects its acceptance in the marketplace. It provides an important, complementary construct for predicting brand extension success and enhancing brand value. Brand Extension 4 Authenticity could be one main component to determine the fit in brand extension. Thus, we hypothesised that: H3: Brand extension authenticity relates positively to perceived brand extension fit. Conceptual Model From the initial review of related research works, Figure 1 represents the conceptual model to be the study framework and guideline of the investigation of this study. Figure 1 Conceptual Model Brand Image Consistency H1 Brand Extension Authenticity Product Feature Similarity H3 Perceived Brand Extension Fit H2 Research Methodology Participants and stimuli brand The participants for the experiment consisted of 100 undergraduate students at Asia-Pacific International University. The hypothetical brand extension was AIU brand, with an extension to water bottle. Table 2 describes the demographic information of the participants in this study. Table 2: Demographic Information Age Less than 19 years old 19 years old 20 years old 21 years old More than 21 years old Gender Male Female No. 9 Sophomore N0. 24 17 Asian (Exclude Thai) 63 19 African 1 14 White/Caucasian 2 41 53 Other Faculty of study Business Administration 10 24 Science 16 Arts and Humanities 32 37 Nursing 2 13 13 47 Student Status Freshman Race/Ethnicity Thai 29 Religious Studies Junior 18 Education and Psychology Senior 16 Measures Brand image consistency The operationalization of this variable uses four items, each measured with seven-point scales. The items are adapted from Vázquez, Del Río, and Iglesias (2002), C. W. Park, 5 Jaworski, and Maclnnis (1986), and Keller (1993). In support of the reliability of the inter item test, the Cronbach's alpha (.96) exceeds .70, the standard cut-off point. Product feature similarity Four items, each measured on a seven-point scale, assess product feature similarity. Vázquez et al. (2002) and Helmig et al. (2007) provide the items, which produce a Cronbach's alpha of .91, exceeds the .70 standard. Brand extension authenticity To measure this variable, the study uses eight items, each measured on a seven-point scale, derived from existing literature on brand extension (Spiggle et al., 2012). The Cronbach's alpha (.815) indicates the items provide good indicators of purchase intentions. Perceived brand extension fit Four items, each measured on a seven-point scale, assess perceived brand extension. Spiggle et al. (2012) provide the items, which produce a Cronbach's alpha of .72, exceeds the .70 standard. Experiments The participants were given a questionnaire contains Asia-Pacific International University brand and its extension - new water bottle products using AIU brand. They were asked to complete the identified brand image consistence scales, product feature similarity scales, brand extension authenticity scales, and perceived brand extension fit scales. Toward the end part of the questionnaire, the subjects were asked to complete the demographic information. Analysis SEM and AMOS 20.0 were used to test the conceptual model. Measurements of the overall fit evaluate how well the model can reproduce the observed variables’ covariance matrix. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI), a descriptive overall measurement, requires a minimum value of .9, and the same threshold applies to the comparative fit index (CFI) and the incremental fit index (IFI). The quotient of χ2 (chi-square test) and degrees of freedom (df), as well as the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), were also employed as important measurements of fit. For the χ2/df measure, a value up to 3.0, and for the RMSEA, a value up to .5 indicate good model fit. The structural equation model meets all these criteria (GFI = .986, CFI = .996, IFI = .996, χ2/df = 2.886, RMSEA = 0.067). Figure 2 shows the measurement models for each construct and the overall structural model, including the standardised coefficients of the different paths. Figure 2: Results of structural equation analysis (N = 100) H1 (.39) Brand Image Consistency H3 (.69) Brand Extension Authenticity (r2=.60) Product Feature Similarity Perceived Brand Extension Fit (r2=.48) H2 (.43) Global Fit Measures: χ2/df = 2.886; RMSEA = 0.067; GFI = .986; CFI = .996; IFI = .996 6 Results The conceptual model captures the important antecedents of perceived brand extension fit. An adequate share (r2=.48) of variance in perceived brand extension fit can be explained. A large share (r2=.60) of variance in brand extension authenticity can be explained. The results indicate support for all hypothesised paths. The relationship between brand image consistency and brand extension authenticity is significantly positive, in support of H1. H2, which posits a positive relationship between product feature similarity and brand extension authenticity, also is supported. In line with H3, the relationship between brand extension authenticity and perceived brand extension fit is significantly positive. Discussion and Implications The researchers determine the total effect (i.e., sum of direct and indirect effects) on perceived brand extension fit. The antecedents that positively affect perceived brand extension fit, separate from brand extension authenticity, are brand image consistency and product feature similarity. Brand extension authenticity explains 69 percent of the total effects on perceived brand extension fit. Furthermore, product feature similarity is stronger influence on perceived brand extension fit than brand image consistency. The result is in contrast with other findings which indicate that brand image consistency has the stronger impact on perceived brand extension fit (Helmig et al., 2007; C. W. Park et al., 1991; Simonin & Ruth, 1998). In the model, there is strong evidence that brand extension authenticity has a strong positive influence on perceived brand extension fit. The result is similar with research finding by Spiggle et al. (2012), who indicate that brand extension authenticity is difference from but complements perceived brand extension fit. The results of this study confirm the power of the use of an established brand name in new product categories. This new category to which the brand is extended can be related or unrelated to the existing product categories. A renowned brand helps an organization to launch products in new categories more easily. In this study, AIU brand core product is education with a likely successful extending to water bottle. Education institution, with tuition fees as its main revenue, could extend its brand outside its core product category to capture the opportunity for the new source of revenue. However, education institution must aware of risks in brand extension. Before extending its brand to other category, the institution must evaluate its product feature similarity, brand image consistency, brand extension authenticity, and perceived brand extension fit. References Aaker, D. A., and Keller, K., L. (1992). The effecfs of sequential introduction of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 29, 35-50. Aaker, D. A., & Keller, K. L. (1990). Consumer Evaluations of Brand Extensions. [Article]. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 27-41. Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of Brand Personality. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 34(3), 347-356. Batra, R., Lenk, P., & Wedel, M. (2010). Brand Extension Strategy Planning: Empirical Estimation of Brand–Category Personality Fit and Atypicality. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 47(2), 335-347. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.47.2.335 Beverland, M. B. (2005). Crafting Brand Authenticity: The Case of Luxury Wines. [Article]. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1003-1029. doi: 10.1111/j.14676486.2005.00530.x 7 Brough, A. R., & Chernev, A. (2012). When Opposites Detract: Categorical Reasoning and Subtractive Valuations of Product Combinations. [Article]. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(2), 399-414. doi: 10.1086/663773 Dickinson, S., & Heath, T. (2006). A comparison of qualitative and quantitative results concerning evaluations of co-branded offerings. [Article]. Journal of Brand Management, 13(6), 393-406. Farquhar, P. H. (1989). Managing Brand Equity. [Article]. Marketing Research, 1(3), 24-33. Helmig, B., Huber, J.-A., & Leeflang, P. (2007). Explaining behavioural intentions toward co-branded products. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(3/4), 285-304. Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, Measuring, Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. [Article]. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22. Keller, K. L. (2003). Strategic brand management: building, measuring and managing brand equity (2 ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Kim, H., & John, D. R. (2008). Consumer response to brand extensions: Construal level as a moderator of the importance of perceived fit. [Article]. Journal of Consumer Psychology (Elsevier Science), 18(2), 116-126. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2008.01.006 Lau, K. C., & Phau, I. (2007). Extending symbolic brands using their personality: Examining antecedents and implications towards brand image fit and brand dilution. [Article]. Psychology & Marketing, 24(5), 421-444. Leuthesser, L., Kohli, C., & Suri, R. (2003). Academic papers 2 +2 =5? A framework focusing co-branding to leverage a brand. [Article]. Journal of Brand Management, 11(1), 35. Park, C. W., Jaworski, B. J., & Maclnnis, D. J. (1986). Strategic Brand Concept-Image Management. [Article]. Journal of Marketing, 50(4), 135-145. Park, C. W., Milberg, S., & Lawson, R. (1991). Evaluation of Brand Extensions: The Role of Product Feature Similarity and Brand Concept Consistency. [Article]. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(2), 185-193. Park, J.-W., Kim, K.-H., & Kim, J. K. (2002). Acceptance of Brand Extensions: Interactive Influences of Product Category Similarity, Typicality of Claimed Benefits, and Brand Relationship Quality. [Article]. Advances in Consumer Research, 29(1), 190-198. Phau, I., & Lau, K. C. (2001). Brand personality and consumer self-expression: Single or dual carriageway? [Article]. Journal of Brand Management, 8(6), 428. Simonin, B. L., & Ruth, J. A. (1998). Is a Company Known by the Company It Keeps? Assessing the Spillover Effects of Brand Alliances on Consumer Brand Attitudes. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 35(1), 30-42. Smith, D. C., & Park, C. W. (1992). Brand Extensions on Market Share and Advertising Efficiency. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 29(3), 296-313. Spiggle, S., Nguyen, H. T., & Caravella, M. (2012). More Than Fit: Brand Extension Authenticity. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 49(6), 967-983. doi: 10.1509/jmr.11.0015 Vázquez, R., Del Río, A. B., & Iglesias, V. (2002). Consumer-based Brand Equity: Development and Validation of a Measurement Instrument. [Article]. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(1/2), 27-48. Yorkston, E. A., Nunes, J. C., & Matta, S. (2010). The Malleable Brand: The Role of Implicit Theories in Evaluating Brand Extensions. [Article]. Journal of Marketing, 74(1), 8093. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.74.1.80 8