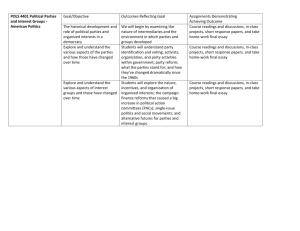

Public Opinion and Democracy - Unit Guide

advertisement

UNIT GUIDE 2015/16 SPAI30008: Public Opinion and Democracy Teaching Block: 2 Weeks: 13 - 24 Unit Owner: Phone: Email: Office: Paula Surridge 0117 928 7689 p.surridge@bristol.ac.uk 1.06, 11 Priory Road Level: Credit points: Prerequisites: Curriculum area: Unit owner office hours: Mondays 11 – 12pm and Thursdays 2 – 3pm H/6 20 None N/A Scheduled office hours do not run during reading weeks, though you can still contact tutors for advice by email and to arrange individual appointments Timetabled classes: Lecture: Monday 10–11am in G.01, 34 Tyndalls Park Road You are also expected to attend ONE seminar each week. Your online personal timetable will inform you to which group you have been allocated. Seminar groups are fixed: you are not allowed to change seminar groups without permission from the office. Weeks 6, 12, 18 and 24 are Reading Weeks; there is NO regular teaching in these weeks. In addition to timetabled sessions there is a requirement for private study, reading, revision and assessments. Reading the essential readings in advance of each seminar is the minimum expectation. The University Guidelines state that one credit point is broadly equivalent to 10 hours of total student input. Learning Outcomes On successful completion of the unit, students will be able to: Critically appraise measures of public opinion Critically discuss the relationship between public opinion and democracy Be able to discuss how public opinion is formed and the role of key agents in this process Understand the impact of social and political change on public opinion Requirements for passing the unit: Satisfactory attendance at seminars Participation in group based seminar presentation Attainment of a composite mark of all summative work to a passing standard (40 or above) Details of coursework and deadlines Assessment: Summative Research Note Summative Essay Word count: 1,000 words Weighting: 25% 2,500 words 75% Deadline: 9.30am on 10th March 2016 9.30am on 25th May 2016 Day: Thursday Summer Assessment Period Summative essay questions will be made available on the SPAIS UG Admin Blackboard site. Instructions for the submission of coursework can be found in Appendix A Assessment in the school is subject to strict penalties regarding late submission, plagiarism and maximum word count. A summary of key regulations is in Appendix B. Marking criteria can be found in Appendix C. 1 Wednesday Week: 19 Make sure you check your Bristol email account regularly throughout the course as important information will be communicated to you. Any emails sent to your Bristol address are assumed to have been read. If you wish for emails to be forwarded to an alternative address then please go to https://wwws.cse.bris.ac.uk/cgi-bin/redirect-mailname-external Unit description This unit is concerned with the formation, sources, measurement and influence of public opinion. It will consider the relationship between public opinion and democracy both in the abstract and in practice. In order to facilitate a critical understanding of public opinion poll data the unit will also cover key topics relevant to the measurement and analysis of public opinion. The unit will focus on the sources of public opinion and how social and political changes in recent decades have changed how the public think and how attitudes are formed. Throughout the unit there is a focus on using empirical data drawn from opinion polls and surveys to address what ‘the public’ thinks. Unit aims Encourage students to think critically about the relationship between public opinion and democracy Offer an overview of the mechanisms by which public opinion is linked to representation Develop an understanding of how public opinion is formed Consider the impact of social and political change on public opinion Understand tools used for the measurement and analysis of public opinion Teaching Methods This is an area characterised by technically sophisticated quantitative empirical work, it is therefore essential for your understanding of the material that you also gain a basic understanding of quantitative social science and its use for measuring public opinion. For this reason some seminars will also cover introductions to key elements of data collection and analysis, including sampling, measurement and multi-variate analysis. No prior knowledge of this is expected and you will be given detailed information and guidance on these topics to inform your wider reading. Transferable skills In addition to an understanding of the formation and significance of public opinion, the unit will also develop key skills in the measurement of public opinion and in understanding and evaluating opinion poll data. Summative assessment There are two pieces of summative work for this unit. The first (25% of the unit mark) is a research note on social cleavages. The second (75% of the unit mark) is a summative essay. Formative assessment Formative assessment for this unit takes the form of peer-reviewed group presentations. Topics and groups will be allocated during seminars in week 1. Development and feedback In most weeks, seminars incorporate group presentations of public opinion data, these will be peer reviewed and will provide a crucial feedback mechanism on students’ understanding of issues in critically evaluating opinion polls. Communication Should you need to contact the unit tutor then you will usually find e-mail is the fastest way to get a response (e-mail p.surridge@bristol.ac.uk). You may also find it useful to ‘follow’ me on twitter (@p_surridge) for details of new and interesting opinion poll data and should regularly check Blackboard for links to new readings and poll data. Blackboard has links to every reading for which an electronic version is available and will be 2 regularly updated with relevant reports from polling organisations, blogs and articles on the 2015 General Election as they appear. Essential reading and Recommended Text books Each seminar has readings taken from text books and journals. These are available as a course reading pack and electronically on blackboard. Three texts cover a considerable amount of the material for the unit: Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press Dalton (2013) Citizen Politics London: Sage Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view Where possible a reading for each session will be specified from these text books and if you are able to purchase one of these it would be helpful to you, however they are expensive and there is no expectation that you will buy any of the books. Earlier editions are available and equally useful for gaining an overview of the debates. The weekly reading lists below are intended to provide a broad overview of a topic and form the basis for further research for the purposes of essay writing, you are encouraged to move beyond the reading list in writing essays using the listed readings and their bibliographies as a starting point. Key Journals The key journals publishing articles in this area are: Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties Public Opinion Quarterly Electoral Studies Political Behaviour British Journal of Political Science European Journal of Political Research European Sociological Review A look through recent issues of the first three of these will be a useful overview of current research issues in this area. Data Resources (please also see Resources section on Blackboard) Market Opinion Research International (MORI) www.mori.com YouGov www.yougov.com Journalists Guide to Opinion Polls http://www.britishpollingcouncil.org/questions.html The National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) www.natcen.ac.uk British Election Survey (BES) www.britishelectionsurvey.com British Social Attitudes Survey www.britsocat.com European Social Survey (ESS) www.europeansocialsurvey.rog World Values Survey www.worldvaluessurvey.org Weekly Programme Week 13: What is public opinion? What is (or should be) its role in democracy? History of Opinion Polls Week 14: Measuring public opinion: What went wrong in 2015? Week 15: The funnel of causality I: Core values Week 16: The funnel of causality II: Social Cleavages Week 17: Biological and Psychological approaches 3 Week 18: Reading Week Week 19: Media effects on public opinion Week 20: Case Study I: Tolerance EASTER BREAK Week 21: Public Opinion and Participation Week 22: The funnel of causality III: Public Opinion and Voting Behaviour Week 23: Case Study II: Trust Week 24: Reading Week Detailed Programme and Readings Week 13: What is public opinion? Lecture material: What is public opinion and how is it related to theories of democracy? Distinguish different roles for public opinion in different theoretical models of democracy What has been the role of the development of the opinion poll in our understanding of public opinion? The history and development of opinion polls Seminar Questions How much do you know about what ‘the public’ think? Should public opinion be taken into account when deciding to go to war? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Blumer, H (1948) ‘Public Opinion and Public Opinion Polling’, American Sociological Review, 13, 542-554 Converse, P (1987) ‘Changing conceptions of public opinion in the Political Process’ Public Opinion Quarterly, 50th Anniversary Supplement 51 s12-s24 Book Chapters Glynn et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd Edition (Chapter 4, p89 - 105) Carpini, M and Keeter, S (1996) What Americans know about politics and why it matters (Chapter 1, pg 22 – 61) Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2004) Public Opinion, 2nd edition Oxford: West view Chapters 1 and 2 Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view Chapters 1, 2 and 4 Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press Chapter 1 Dalton, R (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition London: Sage pp 15 to 21 4 Further reading Carpini, M (1999) ‘In search of the information citizen: What Americans know about politics and why it matters’ The Communication Review 4 129-164 Held, D (2006) Models of Democracy, 3rd edition Stanford: Stanford University Press Keeter, S (2012) ‘Presidential address: Survey Research, its new frontiers and democracy’ Public Opinion Quarterly, 76 (3) 600-608 Key, V. O. (1961) Public Opinion and American Democracy New York: Knopf Lippmann, W (2012 (1922))) Public Opinion Martino Publishing Manza, J and Brooks, C (2012) ‘How sociology lost public opinion: A genealogy of a missing concept in the study of the political’ Sociological Theory, 30 (2) 89-113 Noell-Neumann, E (1979) ‘Public opinion and the classical tradition: A re-evaluation’ Public Opinion Quarterly, 43 (2) 143-156 Walker, J (1966) ‘A critique of the elitist theory of democracy’ American Political Science Review, 60 285295 Worcester, R M (2013) Public Opinion: Friend or Foe? Chancellor’s lecture, University of Kent Week 14: Measuring public opinion: What went wrong in 2015? Lecture material: How is public opinion measured? What went wrong with the polls at the 2015 general election? Seminar questions: Issues in measuring public opinion; sampling, question wording and responses Can the issues with the opinion polls in 2015 be explained by methodology? Please note: Additional readings on the topic of the 2015 ‘polling miss’ are likely to be appearing over the coming weeks. Please check blackboard for additional readings and up to date blog posts. Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Mellon, J and Prosser, C (2015) ‘Investigating the Great British Polling Miss: Evidence from the British election study’ (Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2631165 ) Achen, C (1975) ‘Mass political attitudes and the survey response’ American Political Science Review, 69 (4) 1218-1231 Book chapters Cowley, P and Kavanagh, D (2015) The British General Election of 2015 (Chapter 9). Zaller, J (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion Cambridge: CUP (Chapter 5) (p76-96) Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2004) Public Opinion, 2nd edition Oxford: West view (Chapter 3) Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view (Chapter 3) 5 Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Annex to Chapter 1) Dalton (2013) Citizen Politics 6th edition, London: Sage (Annex A) Further reading Asher, H (2012) Polling and the Public, 8th edition Washington: CQ Press (Chapters 2,3,4) De Vaus. D (2001) Research Design in Social Research London: Routledge Chapter 1-3 De Vaus, D (2001) Surveys in Social Research London: Routledge Bourdieu, P (1984) ‘Public Opinion does not exist’ in Sociology in Question, London: Sage (p149-157) Bourdieu, P (1986) Distinction London: Routledge (Chapter 8) Champagne, P (2005) ‘Making the People Speak’ in Wacquant, L (ed) Pierre Bourdieu and Democratic Politics London: Polity Moser, C and Kalton, G (2004) ‘Questionnaires’ in Seale, C. (2004) Social Research Methods: A Reader. London: Routledge Perrin, A and McFarland, K (2011) ‘Social Theory and Public Opinion’ Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 87107 Tourangeau, R., Rips, L and Rasinski, K (2000) The Psychology of Survey Response Cambridge:CUP (Chap. 6) Sturgis, P. (2008) ‘Designing Samples’, in Gilbert, N. (ed.) Researching Social Life (3rd edition) London: Sage Sturgis, P and Smith, P (2010) ‘Fictitious Issues Revisited: Political Interest, Knowledge and the Generation of Nonattitudes’ Political Studies, 58, 66-84 Zaller, J and Feldman, S (1992) ‘A simple theory of the survey response: Answering questions vs revealing preferences’ American Journal of Political Science, 36 (3) 579-616 Week 15: The funnel of causality I: Core Values Lecture material: Are there underlying values which inform public opinion? If so, how many? What are they? Do these value change? Post-materialism Value change and social change Seminar questions: Are the public post-material? (Student-led presentations) Do the public organise their attitudes around a set of core beliefs and values? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Evans, G et al (1996), ‘Measuring Left-Right and Libertarian-Authoritarian Values in the British Electorate’, British Journal of Sociology, 47:1 Inglehart, R (2008) ‘Changing Values among Western Publics from 1970 to 2006’, West European Politics, 31:1-2, 130-146 6 Brooks, C and Manza, J (1994) ‘Do changing values explain the new politics? A critical assessment of the post-materialist thesis’ Sociological Quarterly, 35 (4) 541-570 Feldman, S (1988) ‘Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values’ American Journal of Political Science 32 416-438 Book chapters Dalton, R.J. (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press Chapter 5 (p87-104) Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2004) Public Opinion, 2nd edition Oxford: West view (Chapter 8) Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view (Chapter 9) Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 5) Dalton, R.J. (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 6) Further reading Abramson, P and Inglehart, R (1992) ‘Generational replacement and value change in eight West European Societies’ British Journal of Political Science 22 (2) 183-228 Bornschier, S (2010) ‘The New Cultural Divide and the Two-Dimensional Political Space in Western Europe’ West European Politics, 33:3, 419-444 Converse P (2006) The nature of belief systems in mass publics (1964), Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society,18:1-3, 1-74 Fleishman, J.A. (1988) ‘Attitude organization in the general public: evidence for a bi-dimensional structure’ Social Forces 67 159-84 Heath, A., Evans, G and Martin, J. (1994) ‘The measurement of core beliefs and values: the development of balanced socialist/laissez fair and libertarian/authoritarian scales’ British Journal of Political Science 24 115158 Inglehart, R. (1977) The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics Princeton: Princeton University Press Inglehart, R and Flanagan, S (1987) ‘Value change in industrial societies’ American Political Science Review 81 (4) 1289-1319 Jacoby, W. G. (2006) ‘Value Choices and American Public Opinion’ American Journal of Political Science 50 (3) 706-723 Kriesi, H (2010) ‘Restructuration of partisan politics and the emergence of a new cleavage based on values’ West European Politics 33 (3) 673-685 Surridge, P (2012) ‘A reactive core? The configuration of values in the British electorate 1986-2007’ Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 22 (1) 51-76 Week 16: The funnel of causality II: Social Cleavages Lecture material: Sociological theories of public opinion Social cleavages: Class, Education, Age and Religion 7 Seminar questions: Is public opinion rooted in social groups? (Student-led presentations) What are social cleavages? Are they relevant to 21st Century public opinion? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Elff, Martin. 2007. “Social Structure and Electoral Behavior in Comparative Perspective: The Decline of Social Cleavages in Western Europe Revisited.” Perspectives on politics 5(02): 277–294 Kriesi, H (1998) ‘The transformation of cleavage politics: The 1997 Stein Rokkan lecture’ European Journal of Political research 33 (2) 165 – 185 Book chapters Manza, J. and Brooks, C. (1999) Social cleavages and political change : voter alignments and U.S. party coalitions, Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Chapter 1) (p9-31) Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2004) Public Opinion, 2nd edition Oxford: West view (Chapters 4 and 5) Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ (Chapter 2, 6 and 7) Dalton, R.J. (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 8) Further reading Bengtsson, M et al (2013) ‘Class and ideological orientations revisited: an exploration of class-based mechanisms’ British Journal of Sociology 64 (4) 691 - 716 Brint, S (1985) ‘The political attitudes of professionals’ Annual Review of Sociology 11 389-414 Jennings, M. and Niemi, R. (1968) ‘The transmission of political values from parent to child’ American Political Science Review 62 (1): 169-184 Evans, G and De Graaf, N (eds) (2013) Political Choice Matters Oxford: OUP Evans, G and Tilley, J (2012) ‘The depoliticization of inequality and redistribution: explaining the decline of class voting’ Journal of Politics 74 (4) 963-976 Kriesi, H et al (2008) West European Politics in the age of globalisation Cambridge: CUP Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. 1967. Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction. In S. M. Lipset & S. Rokkan (Eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments (pp. 1-64). New York-London: The Free Press-Collier-Macmillan. Paterson, L. (2008) ‘Political attitudes, social participation and social mobility: a longitudinal analysis’, British Journal of Sociology, 59, 413-434 Stubager, R (2010) ‘The development of the education cleavage: Denmark as a critical case’ West European Politics 33 505-33 Surridge, P (Forthcoming, 2016) ‘Education and liberalism: Pursuing the link’ Oxford Review of Education Tilley, J (2015) ‘We don’t do God? Religion and Party Choice in Britain’ British Journal of Political Science 45 907 - 927 8 Van de Werfhost, H.G and de Graaf, N. D. (2004) ‘The sources of political orientations in post-industrial society: social class and education revisited’ British Journal of Sociology, 55, 211-235. Weakliem, D.L. (2002) ‘The effects of education on political opinions: an international study’ International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 13, 141-157. Week 17: Biological and Psychological approaches Lecture material: Evidence for a genetic basis for political attitudes The ‘Big 5’ personality traits and their effect on politics Seminar questions: Is public opinion underpinned by personality? (Student-led presentations) Are political opinions in our genes? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Alford, J, Funk, C and Hibbing, J (2005) ‘Are political orientations genetically transmitted?’ American Political Science Review 99 (2) 153-167 Charney, E (2008) ‘Genes and Ideologies’ Perspectives on Politics 6 (2) 299 – 319 Gerber, A et al (2011) ‘The big five personality traits in the political arena’ Annual Review of Political Science 14 (265-87) Recommended readings from core textbooks Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ (pg 61 – 64) Further reading Brader, T (2005) ‘Striking a responsive chord: How political ads motivate and persuade voters by appealing to emotions’ American Journal of Political Science 49 (2) 388-405 Caprara, G et al (2006) ‘Personality and Politics: Values, traits and political choice’ Political Psychology 27 (1) 1 - 28 Conover, P and Feldman, S (1986) ‘Emotional reactions to the economy’ American Journal of Political Science 30, 30-78 Funk, C et al (2013) ‘Genetic and environmental transmission of political orientations’ Political Psychology 34 (6) 805-819 Gallego, A and Pardos-Prado, S (2014) ‘The big five personality traits and attitudes towards immigrants’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (1) 79-99 Hibbing, J., Smith, K. and Alford, J (2014) Predisposed: Liberals, Conservatives and the Biology of Political Differences New York: Routledge Jost, J et al (2014) ‘Political NeuroScience: the beginning of a beautiful friendship’ Advances in Political Psychology 35 3 - 42 Marcus, G (2000) ‘Emotions in Politics’ Annual Review of Political Science 3 221-50 9 Mondak, J (2010) Personality and the Foundations of Political Behaviour Cambridge: CUP Simon, H (1985) ‘Human nature is politics: The dialogue of psychology and political science’ American Political Science Review 79 293-304 Smith, K, Alford, J, Hatemi, P, Eaves, L, Funk, C and Hibbing, J (2012) ‘Biology, Ideology and Epistemology: How do we know political attitudes are inherited and why should we care?’ American Journal of Political Science 56 (1) 17-33 Sturgis, P. et al. (2010) ‘A genetic basis for social trust?’ Political Behaviour 32 205-230 Week 18: Reading Week (No classes) Week 19: Media effects on public opinion Lecture material: How does the media influence public opinion? Models of media effects The role of the media in generating opinion New media and public opinion Seminar questions: How is the media influencing public opinion about immigration? (All students to bring in examples) Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Scheufele, D. A. and Tewksbury, D. (2007) ‘Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models’ Journal of Communication, 57: 9–20 Book Chapters Lahav, G. (2013) ‘Threat and Immigration Attitudes in Liberal Democracies’ in Freeman, G et al (eds) Immigration and Public Opinion in Liberal Democracies Abingdon: Routledge (p232-253) Roessler, P (2008) ‘Agenda-setting, framing and priming’ in Donsbach, W. and Trougott, M. The Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research London: Sage (p205 – 218) Reports Allen, W and Blinder, S. (2013) “Migration in the News: Portrayals of Immigrants, Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in National British Newspapers, 2010 to 2012.” Migration Observatory report, COMPAS, University of Oxford. (available at http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/sites/files/migobs/Report%20%20migration%20in%20the%20news.pdf) Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2004) Public Opinion, 2nd edition Oxford: West view (Chapter 10) Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view (Chapter 11) Clawson, R. A. and Oxley, Z. M. (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd Edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 3) 10 Further reading Chong, D and Druckman, J (2007) ‘Framing public opinion in competitive democracies’ American Political Science Review 101 (4) 637-655 Cowley, P and Kavanagh, D (2015) The British General Election of 2015 (Chapter 12) Dean, M (2013) Democracy Under Attack: How the media distort policy and politics Bristol: Policy Press Druckman, J and Lupia, A (2000) ‘Preference formation’ Annual Review of Political Science 3, 1-24 Farrell, H (2012) ‘The consequences of the internet for politics’ Annual Review of Political Science 15 (1) 35-52 Freeman, G et al (eds) Immigration and Public Opinion in Liberal Democracies Abingdon: Routledge Krosnick, J. and Kinder, D. (1990) ‘Altering the foundations of support for the President through priming’, The American Political Science Review. 84: 497-512 McCombs, M (2014) Setting the Agenda, 2nd edition Cambridge: Polity Chapter 1 (on order)(p1-23) McCombs, M and Shaw, D (1972) ‘The agenda-setting function of the mass media’ Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2) 176-187 McCombs, M., Holbert, L., Kiousis, S. and Wanata, W (2011) The News and Public Opinion London: Polity Stroud, N. (2008) ‘Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure’ Political Behaviour 30 341-366 Swigger, N (2013) ‘The online citizen: Is social media changing citizens’ beliefs about democratic values?’ Political Behaviour 35 589-603 Theocharis, Y (2011) ‘Cuts, tweets, solidarity and mobilisation: how the internet shaped the student occupations’ Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1) 162-194 Zaller, J (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion Cambridge: CUP Zaller, J 91998) ‘Monica Lewinsky’s contribution to political science’ PS: Political Science and Politics 31 (2) 182-189 Week 20: Case Study I: Are the public tolerant? Lecture material: What is tolerance? How can it be measured? Are the public tolerant? Variations within groups Seminar questions: Are the public tolerant? (Student led presentations) Can the rise in UKIP support be explained by a lack of tolerance among some groups of the UK public? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Ford, R. (2008), Is racial prejudice declining in Britain? The British Journal of Sociology, 59: 609–636 Gibson, J (2013) ‘Measuring political tolerance and general support for pro-civil liberties policies’ Public Opinion Quarterly, 77, Special Issue, 2013, pp. 45–68 11 Book chapters Clawson and Oxley (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd edition, Chapter 9 (p241-272) Gibson, J (2009) ’Political Tolerance in the context of democratic theory’ in Dalton, R and Klingemann, H The Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour Oxford: OUP pages (323 – 341) Reports Heath, A and Ford, R (2014) ‘Immigration’ in British Social Attitudes Report, 32 (Available here: http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/downloads/bsa-31-downloads.aspx) (NB: Full chapter download not early release). Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view (pg 266-278) Clawson and Oxley (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd edition, Chapter 9 (p241-272) Further reading Blinder, S. (2011) ‘UK Public Opinion toward Migration: Determinants of Attitudes.’ Migration Observatory briefing, COMPAS, University of Oxford Davis, D. W. and Silver, B. D. (2004), ‘Civil Liberties vs. Security: Public Opinion in the Context of the Terrorist Attacks on America’ American Journal of Political Science, 48: 28–4 Ford, R. (2011) ‘Acceptable and Unacceptable immigrants: How opposition to immigration in Britain is affected by migrants region of origin’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (7) 1019-1037 Ford, R. and Goodwin, M. J. (2010), Angry White Men: Individual and Contextual Predictors of Support for the British National Party. Political Studies, 58: 1–25. Gibson, J (2013) ‘Measuring political tolerance and general support for pro-civil liberties policies’ Public Opinion Quarterly 77 45-68 Hurwitz, J and Mondak, J (2002). ‘Democratic Principles, Discrimination and Political Intolerance’. British Journal of Political Science, 32, pp93-118 Lipset, M. S. (1959) ‘Democracy and working-class authoritarianism’ American Sociological Review 24 482502 Marcus, G, Sullivan, J, Theiss-Morse, E and Wood, S (1995) With Malice Toward Some, Cambridge: CUP McClosky, H. and Brill, A. 1983 Dimensions of Tolerance. What Americans believe about Civil Liberties New York: Russell Sage Foundation Mondak, J. J. and Sanders, M.S. (2003) ‘Tolerance and Intolerance, 1976-1998’ American Journal of Political Science 47 (3) 492-502 Park, A. and Surridge, P. 2003 ‘Charting change in British Values’ in Park et al (eds) British Social Attitudes: The 20th Report London: Sage Phelan, J., Link, B., Stueve, A. and Moore, R. (1995) ‘Education, social liberalism and economic conservatism: Attitudes toward homeless people’ American Sociological Review 60 (1) 126-40 12 Tilley, J (2005) ‘Libertarian-authoritarian value change in Britain, 1974-2001’ Political Studies 53 (2) 442453 Week 21: Public Opinion and Participation Lecture material: Political participation Who votes and why? Seminar questions: Why do people vote? (Student led presentations) How is political participation influenced by political attitudes? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Welzel, C., Inglehart, R. & Franziska Deutsch (2005) Social capital, voluntary associations and collective action: Which aspects of social capital have the greatest ‘civic’ payoff? Journal of Civil Society, 1:2, 121146 Blais, A (2006) ‘What affects voter turnout?’ Annual Review of Political Science 9 111-125 Book Chapter Whiteley, P (2012) Political Participation in Britain Basingstoke: Palgrave (Chapter 3) (p34-56) Recommended readings from core textbooks Dalton, R.J. (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 3 and 4) Further reading Blais, A. and Dobrzynska, A. (1998) ‘Turnout in electoral democracies’, European journal of political research., 33: 239-261 Geys, B. (2006) ‘Explaining voter turnout: a review of aggregate-level research’, Electoral studies. 25: 637663. Leighley, J. and Nagler, J. (1992) ‘Individual and systemic influences on turnout: who votes? ’, The Journal of politics., 54: 718-740. Lister, M (2007) ‘Institutions, inequality and social norms: Explaining variations in participation’ British Journal of Politics and International Relations 9 (1) 20 – 35 Norris, P (2011) Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited Cambridge: CUP Norris, P., Walgrave, S. and Aelst (2005) ‘Who Demonstrates? Antistate rebels, conventional participants or everyone?’ Comparative Politics 37 (2) 189-205 Paterson, L (2014) ‘Education, social attitudes and social participation among adults in Britain’ Sociological Research Online 19 (1) 17 Pattie, C, Seyd, P and Whiteley, P (2004) Citizenship in Britain. Values, Participation and Democracy, Cambridge: CUP 13 Putnam, R (2000) Bowling Alone: The collapse and Revival of American Community New York: Simon and Schuster Rallings, C. and Thrasher, M. (2005) ‘Not all “second-order” contests are the same: turnout and party choice at the concurrent 2004 local and European Parliament elections in England’, British Journal of Politics & International Relations. 7: 584-597 Teorell, J (2006) ‘Political participation and Three Theories of Democracy: A Research Inventory and Agenda’ European Journal of Political research 45 (5) 787-810 Week 22: Funnel of Causality III: Public Opinion and Voting Behaviour Lecture material: What are the key influences on electoral behaviour? How does public opinion relate to voting? Seminar questions: Who would win a general election held tomorrow? (All students to bring recent opinion poll data) Do attitudes influence voting behaviour? Why did Labour lose in 2015? Please note: Additional readings on the topic of the 2015 General Election are likely to be appearing over the coming weeks. Please check blackboard for additional readings and up to date blog posts. Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Clarke, H, Sanders, D, Stewart, M and Whiteley, P (2011) ‘Valence politics and electoral choice in Britain in 2010’ Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 21 (2) 237-253 Book chapters Van der Eijk, C and Franklin, M (2009) Elections and Voters Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan (Chapter 6) (p146-178) Other Curtice, J (2015) ‘A defeat to reckon with: On Scotland, economic competence, and the complexities of Labour's losses’ Juncture 22 (1) Green, J and Prosser, C (2015) ‘Learning the right lessons from Labour’s 2015 defeat’ Juncture 22 (2) Recommended readings from core textbooks Glynn, C.J. et al (2015) Public Opinion, 3rd edition Oxford: West view (pg 240 – 246) Dalton, R.J. (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 9 and 10) Further reading Borges, W, Clarke, H, Stewart, M, Sanders, D and Whiteley, P (2013) ‘The emerging political economy of austerity Britain’ Electoral Studies 32 396-403 14 Brooks, C (2014) ‘Introduction: Voting behaviour and elections in context’ The Sociological Quarterly 55 587-595 Clarke, H, Sanders, D, Stewart, M and Whiteley, P (2009) Performance Politics and the British Voter Cambridge: CUP Clarke, H, Sanders, D, Stewart, M and Whiteley, P (2011) ‘Valence politics and electoral choice in Britain in 2010’ Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 21 (2) 237-253 Cowley, P and Kavanagh, D (2015) The British General Election of 2015 (Chapter 12) Curtice, J (2002) ‘The state of election studies: mid-life crisis or new youth? Electoral Studies 21 (2) 161168 Denver, D (2007) Elections and Voters in Britain Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan Evans, J (2004) Voters and Voting London: Sage Ford, R and Goodwin, M (2014) Revolt on the Right London: Routledge Franklin, M and Hughes, C (1999) ’Dynamic Representation in Britain’ in Evans, G and Norris,P (eds) Critical Elections? British Voters and Parties in the Long-term perspective London: Sage Geddes, A and Tonge, J (eds) (2015) Britain Votes, 2015 Oxford: OUP Goodwin, M and Milazzo, C (2015) UKIP: Inside the campaign to redraw the map of British Politics Oxford: OUP Johnston, R and Pattie, C (2010) ‘Where did Labour’s votes go? Valence politics and campaign effects at 2010 British General Election’ British Journal of Politics and International Relations 13 283 – 303 Lewis-Beck, M and Stegmaier, M (2000) ‘Economic determinants of Electoral Outcomes’ Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1) 88-219 Sanders, D et al (2014) ‘The calculus of ethnic minority voting in Britain’ Political Studies 62 230-251 Whiteley, P, Clarke, H, Sanders, D and Stewart, M (2013) Affluence, Austerity and Electoral Change Cambridge: CUP Week 23: Case study II: Trust Lecture material: Why does trust matter? Trust as social capital Who do the public trust? Seminar questions: Do the public trust political institutions and politicians? (Student led presentations) Is trust in political institutions important in 21st Century Britain? Essential readings (in reading pack) Journal articles Dalton, R (2005) ‘The social transformation of trust in government’ International Review of Sociology 15 (1) 133-154 15 Hetherington, M. J. and Husser, J. A. (2012), How Trust Matters: The Changing Political Relevance of Political Trust. American Journal of Political Science, 56: 312–325 Seyd, B (2015) ‘How do citizens evaluate public officials?’ Political Studies 63 (S1) 73 – 90 Reports Phillips, M and Simpson, I (2015) ‘Politics’ in British Social Attitudes Report, 32 Recommended readings from core textbooks Clawson and Oxley (2013) Public Opinion, 2nd edition, Chapter 11 (p303-336) Dalton, R.J. (2013) Citizen Politics, 6th edition Thousand Oaks: CQ Press (Chapter 12) Further reading Bromley, C., Curtice, J. & Seyd, B. (2002) ‘Confidence in government’, in British Social Attitudes Survey, the 18th Report Delhey, J and Newton, K (2005) ‘Predicting cross-national levels of trust’ European Sociological Review 21 (4) 311-327 Hetherington, M (1998) ‘The political relevance of political trust’ American Political Science Review 92 (4) 791-808 Levi, M and Stoker, L (2000) ‘Political trust and trustworthiness’ Annual Review of Political Science 30 475508 Li, Y, Pickles, A and Savage, M (2005) ‘Social capital and social trust in Britain’ European Sociological Review 21, 2 109-123 McLaren, L (2007) ‘Explaining mass-level Euroscepticism: Identity, Interests and Institutional Distrust’ Acta Politica 42 233-251 Pattie, C, Seyd, P and Whitely, P (2004) Citizenship in Britain. Values, Participation and Democracy, Cambridge: CUP Putnam, R (2000) Bowling Alone: The collapse and Revival of American Community New York: Simon and Schuster Sturgis, P and Smith, P (2010) ‘Assessing the validity of generalised trust questions, what kind of trust are we measuring?’ International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 22 (1) 74-92 Week 24: Reading Week (No classes) 16 Appendix A Instructions on how to submit essays electronically 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Log in to Blackboard and select the Blackboard course for the unit you are submitting work for. If you cannot see it, please e-mail spais-ug@bristol.ac.uk with you username and ask to be added. Click on the "Submit Work Here" option at the top on the left hand menu and then find the correct assessment from the list. Select ‘view/complete’ for the appropriate piece of work. It is your responsibility to ensure that you have selected both the correct unit and the correct piece of work. The screen will display ‘single file upload’ and your name. Enter your name (for FORMATIVE ASSESSMENTS ONLY) or candidate number (for SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENTS ONLY) as a submission title, and then select the file that you wish to upload by clicking the ‘browse’ button. Click on the ‘upload’ button at the bottom. You will then be shown the essay to be submitted. Check that you have selected the correct essay and click the ‘Submit’ button. This step must be completed or the submission is not complete. You will be informed of a successful submission. A digital receipt is displayed on screen and a copy sent to your email address for your records. Important notes You are only allowed to submit one file to Blackboard (single file upload), so ensure that all parts of your work – references, bibliography etc. – are included in one single document and that you upload the correct version. You will not be able to change the file once you have uploaded. Blackboard will accept a variety of file formats, but the School can only accept work submitted in .rtf (Rich Text Format) or .doc/.docx (Word Document) format. If you use another word processing package, please ensure you save in a compatible format. By submitting your essay, you are confirming that you have read the regulations on plagiarism and confirm that the submission is not plagiarised. You also confirm that the word count stated on the essay is an accurate statement of essay length. If Blackboard is not working email your assessment to spais-ug@bristol.ac.uk with the unit code and title in the subject line. How to confirm that your essay has been submitted You will have received a digital receipt by email and If you click on the assessment again (steps 1-4), you will see the title and submission date of the essay you have submitted. If you click on submit, you will not be able to submit again. This table also displays the date of submission. If you click on the title of the essay, it will open in a new window and you can also see what time the essay was submitted. Appendix B Summary of Relevant School Regulations (Further information is in the year handbook) Attendance at classes SPAIS takes attendance and participation in classes very seriously. Seminars form an essential part of your learning and you need to make sure you arrive on time, have done the required reading and participate fully. Attendance at all seminars is monitored, with absence only condoned in cases of illness or for other exceptional reasons. If you are unable to attend a seminar you must inform your seminar tutor, as well as email spaisabsence@bristol.ac.uk. You should also provide evidence to explain your absence, such as a selfcertification and/or medical note, counselling letter or other official document. If you are unable to provide evidence then please still email spais-absence@bristol.ac.uk to explain why you are unable to attend. If you are ill or are experiencing some other kind of difficulty which is preventing you from attending seminars for a prolonged period, please inform your personal tutor, the Undergraduate Office or the Student Administration Manager. 17 Requirements for credit points In order to be awarded credit points for the unit, you must achieve: Satisfactory attendance in classes, or satisfactory completion of catch up work in lieu of poor attendance Satisfactory formative assessment An overall mark of 40 or above in the summative assessment/s. In some circumstances, a mark of 35 or above can be awarded credit points. Presentation of written work Coursework must be word-processed. As a guide, use a clear, easy-to-read font such as Arial or Times New Roman, in at least 11pt. You may double–space or single–space your essays as you prefer. Your tutor will let you know if they have a preference. All pages should be numbered. Ensure that the essay title appears on the first page. All pages should include headers containing the following information: Formative work Name: e.g. Joe Bloggs Unit e.g. SOCI10004 Seminar Tutor e.g. Dr J. Haynes Word Count .e.g. 1500 words Summative work **Candidate Number**: e.g. 12345 Unit: e.g. SOCI10004 Seminar Tutor: e.g. Dr J. Haynes Word Count: e.g. 3000 words Candidate numbers are required on summative work in order to ensure that marking is anonymous. Note that your candidate number is not the same as your student number. Assessment Length Each piece of coursework must not exceed the stipulated maximum length for the assignment (the ‘word count’) listed in the unit guide. Summative work that exceeds the maximum length will be subject to penalties. The word count is absolute (there is no 10% leeway, as commonly rumoured). Five marks will be deducted for every 100 words or part thereof over the word limit. Thus, an essay that is 1 word over the word limit will be penalised 5 marks; an essay that is 101 words over the word limit will be penalised 10 marks, and so on. The word count includes all text, numbers, footnotes/endnotes, Harvard referencing in the body of the text and direct quotes. It excludes, the title, candidate number, bibliography, and appendices. However, appendices should only be used for reproducing documents, not additional text written by you. Referencing and Plagiarism Where sources are used they must be cited using the Harvard referencing system. Inadequate referencing is likely to result in penalties being imposed. See the Study Skills Guide for advice on referencing and how poor referencing/plagiarism are processed. Unless otherwise stated, essays must contain a bibliography. Extensions Extensions to coursework deadlines will only be granted in exceptional circumstances. If you want to request an extension, complete an extension request form (available at Blackboard/SPAIS_UG Administration/forms to download and School policies) and submit the form with your evidence (e.g. self-certification, medical certificate, death certificate, or hospital letter) to Catherine Foster in the Undergraduate Office. Extension requests cannot be submitted by email, and will not be considered if there is no supporting evidence. If you are waiting for evidence then you can submit the form and state that it has been requested. All extension requests should be submitted at least 72 hours prior to the assessment deadline. If the circumstance occurs after this point, then please either telephone or see the Student Administration Manager in person. In their absence you can contact Catherine Foster in the UG Office, again in person or by telephone. 18 Extensions can only be granted by the Student Administration Manager. They cannot be granted by unit convenors or seminar tutors. You will receive an email to confirm whether your extension request has been granted. Submitting Essays Formative essays Summative essays Unless otherwise stated, all formative essay All summative essay submissions must be submissions must be submitted electronically via submitted electronically via Blackboard. Blackboard Electronic copies enable an efficient system of receipting, providing the student and the School with a record of exactly when an essay was submitted. It also enables the School to systematically check the length of submitted essays and to safeguard against plagiarism. Late Submissions Penalties are imposed for work submitted late without an approved extension. Any kind of computer/electronic failure is not accepted as a valid reason for an extension, so make sure you back up your work on another computer, memory stick or in the cloud (e.g. Google Drive or Dropbox). Also ensure that the clock on your computer is correct. The following schema of marks deduction for late/non-submission is applied to both formative work and summative work: Up to 24 hours late, or part thereof For each additional 24 hours late, or part thereof Assessment submitted over one week late Penalty of 10 marks A further 5 marks deduction for each 24 hours, or part thereof Treated as a non-submission: fail and mark of zero recorded. This will be noted on your transcript. The 24 hour period runs from the deadline for submission, and includes Saturdays, Sundays, bank holidays and university closure days. If an essay submitted less than one week late fails solely due to the imposition of a late penalty, then the mark will be capped at 40. If a fail due to non-submission is recorded, you will have the opportunity to submit the essay as a second attempt for a capped mark of 40 in order to receive credit points for the unit. Marks and Feedback In addition to an overall mark, students will receive written feedback on their assessed work. The process of marking and providing detailed feedback is a labour-intensive one, with most 2-3000 word essays taking at least half an hour to assess and comment upon. Summative work also needs to be checked for plagiarism and length and moderated by a second member of staff to ensure marking is fair and consistent. For these reasons, the University regulations are that feedback will be returned to students within three weeks of the submission deadline. If work is submitted late, then it may not be possible to return feedback within the three week period. Fails and Resits If you fail the unit overall, you will normally be required to resubmit or resit. In units where there are two pieces of summative assessment, you will normally only have to re-sit/resubmit the highest-weighted piece of assessment. Exam resits only take place once a year, in late August/early September. If you have to re-sit an exam then you will need to be available during this period. If you are not available to take a resit examination, then you will be required to take a supplementary year in order to retake the unit. 19 Appendix C Level 6 Marking and Assessment Criteria (Third / Final Year) 1st (70+) o o o o o 2:1 (60–69) o o o o o 2:2 (50–59) o o o o o 3rd (40–49) o o o o o Marginal o Fail o (35–39) o o o Excellent comprehension of the implications of the question and critical understanding of the theoretical & methodological issues A critical, analytical and sophisticated argument that is logically structured and well-supported Evidence of independent thought and ability to ‘see beyond the question’ Evidence of reading widely beyond the prescribed reading list and creative use of evidence to enhance the overall argument Extremely well presented: minimal grammatical or spelling errors; written in a fluent and engaging style; exemplary referencing and bibliographic formatting Very good comprehension of the implications of the question and fairly extensive and accurate knowledge and understanding Very good awareness of underlying theoretical and methodological issues, though not always displaying an understanding of how they link to the question A generally critical, analytical argument, which shows attempts at independent thinking and is sensibly structured and generally well-supported Clear and generally critical knowledge of relevant literature; use of works beyond the prescribed reading list; demonstrating the ability to be selective in the range of material used, and the capacity to synthesise rather than describe Very well presented: no significant grammatical or spelling errors; written clearly and concisely; fairly consistent referencing and bibliographic formatting Generally clear and accurate knowledge, though there may be some errors and/or gaps and some awareness of underlying theoretical/methodological issues with little understanding of how they relate to the question Some attempt at analysis but a tendency to be descriptive rather than critical; Tendency to assert/state opinion rather than argue on the basis of reason and evidence; structure may not be entirely clear or logical Good attempt to go beyond or criticise the ‘essential reading’ for the unit; but displaying limited capacity to discern between relevant and non-relevant material Adequately presented: writing style conveys meaning but is sometimes awkward; some significant grammatical and spelling errors; inconsistent referencing but generally accurate bibliography. Limited knowledge and understanding with significant errors and omissions and generally ignorant or confused awareness of key theoretical/ methodological issues Largely misses the point of the question, asserts rather than argues a case; underdeveloped or chaotic structure; evidence mentioned but used inappropriately or incorrectly Very little attempt at analysis or synthesis, tending towards excessive description Limited, uncritical and generally confused account of a narrow range of sources Poorly presented: not always easy to follow; frequent grammatical and spelling errors; limited attempt at providing references (e.g. only referencing direct quotations) and containing bibliographic omissions. Unsatisfactory level of knowledge and understanding of subject; limited or no understanding of theoretical/methodological issues Very little comprehension of the implications of the question and lacking a coherent structure Lacking any attempt at analysis and critical engagement with issues, based on description or opinion Little use of sources and what is used reflects a very narrow range or are irrelevant and/or misunderstood Unsatisfactory presentation: difficult to follow; very limited attempt at providing references (e.g. only referencing direct quotations) and containing bibliographic omissions 20 Outright Fail (0–34) o o o o o Very limited, and seriously flawed, knowledge and understanding No comprehension of the implications of the question and no attempt to provide a structure No attempt at analysis Limited, uncritical and generally confused account of a very narrow range of sources Very poorly presented: lacking any coherence, significant problems with spelling and grammar, missing or no references and containing bibliographic omissions 21