File

advertisement

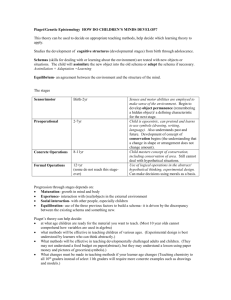

Applying first world theories to third world education: a study of the application of Piagetian theory to Ugandan Education Practices Student Number: Module Code: Tutor: Assessment Criteria: AL3, BL3, CL3, FL3, GL3. Word Count: 8602 Pages: 41 1 Abstract: This study aims to use a library based research approach to investigate the concept of using theories such as Piaget’s Constructivism theories in the educational policies and practices of Ugandan education. As well as this it will examine the current educational practices within Uganda and the outside factors which contribute to any issues experienced by the children in Uganda in receiving their education, such as poverty, lifestyle, lack of funding and lack of available teachers. Using previous reports on the state of education in Uganda as well as work on Piaget’s theories, both supporting and critiquing, this study will attempt to establish whether or not Western theories can be considered universal and therefore whether or not learning is a universal process or one which differs in response to cultural, social and political differences. 2 Introduction Throughout the three years of this course various theorists have been covered and the educational policies and practices of other countries have been referred to; this study aims to combine the two and investigate whether or not educational theories are universal or change depending on social, economic and cultural differences by taking Piaget’s ‘cognitive development theory’ and applying it to educational policies and classroom initiatives in Uganda. The deliberation of whether or not theories such as Piaget’s ‘CognitiveDevelopment Theory’ can be applied to the teaching practices in third world counties such as those in Uganda are of interest when one is considering voluntary teaching in these areas. In particular this study will focus on the teaching principles in Uganda as this is an area which has lately received much publicity through films such as ‘Machine Gun Preacher’ released in November 2011 (IMDB) and the recent viral spread of a thirty minute campaign video by Invisible Children which urged viewers to get involved through donations and by spreading the video to raise awareness (Kony2012). The film and the campaign focus on the atrocities committed by Joseph Kony during a twenty year tirade on Ugandan people, forcing children to become child sex slaves and child soldiers. Although it is true that Kony has now left Uganda and moved on to terrorising other African counties the damage he has left behind is still an ongoing problem and it is felt that there is much need for a rebuilding of schools and introduction of a firm 3 education for the children of Uganda. However, as many criticisms of the viral video have suggested, it may not always be appropriate for those from across the world to become involved in situations they have little or no knowledge of without considering the opinions of the people involved themselves. In regards to the Kony2012 video this was highlighted by outcry from victims in Uganda who objected to the video (the guardian 2012). It is important to consider whether the interruption of Western theories into Ugandan education might also have the same unwelcome and insulted response, although of course Uganda was a part of the British Empire until 1962 and the English language is the official language of the country, though not many speak it as a mother tongue (Jelmert Jorgensen 1981). Firstly Piaget’s theories are of interest when considering the cognitive development of any child. Can a child’s learning and development be documented and judged by a set standard of age defined guidelines, and if so can there be exceptions to this? Predominantly Piaget’s theories rely on an adult or significant more knowledgeable other to initiate learning and then assume the child will continue to learn and increase comprehension through their own desire for knowledge (Long 2000). This study hopes to test the validity of these claims and question whether or not a child has an inbuilt desire to learn or if Piaget may have been making assumptions in his knowledge of child psychology. Psychology, particularly psychology of children, has been a keen interest of mine since before starting this course as for some time I considered becoming a psychiatrist before choosing the role of educator. At A-Level I studied English Language and first came across Piaget’s stages of cognition 4 when exploring how children first learn to speak and interact. Whilst studying this I realised that a sound knowledge of how children learn is not simply important for educators but also for parents, an aim of which I have always had regardless of my career choices. I have continuously questioned Piaget’s ‘stages of development’ (Piaget 1972) after witnessing my own young relative reach each stage at a more delayed time than Piaget suggests. However later my niece did come to meet Piaget’s guidelines and it was suggested that only a level of shyness had kept her from outwardly expressing her inner cognitive developments. This ambiguity has stirred my curiosity and I aim to further investigate the validity of Piaget’s work throughout this study. The reason I have chosen to apply Piaget’s theories to education in Uganda, other than because of the popular media Uganda has been receiving, is due to a desire I have to work abroad in developing countries for some time after graduation. Partly my interest stems from a desire to see the world but mostly I hope to come to understand their culture and thus grow to appreciate our cultural differences and similarities, helping in whatever way I am able, if possible. To thoroughly understand education in Uganda I must attempt to thoroughly understand the Ugandan lifestyle; its history, its policy, its people and its way of life. To do this I will thoroughly research life in Uganda using books written by those who have done studies in Uganda and, possibly more importantly, by those who have experienced life in Uganda. I will consult Ugandan government websites, historical documents and other researchers work in an 5 attempt to gain a complete view of Ugandan life in order to understand the value and importance of education for its people. I intend to cover all aspects of Ugandan education from the almost nonexistent pre-school to University level. With the instigation of the UPE (Universal Primary Education) initiative in 1997, which stated that primary education for the first four children in each family would be provided for free in an attempt to increase access to education, there have been many changes in Ugandan education in recent years – more access, more funds and a closing in the gap between male and female students who attend primary schools (Pascal Al Amin 2012). This was further improved in 2007 when secondary education was made free as well. This would seem like a strong victory for education however across Uganda there is opposition and resentment of the notion of having this free education forced on them as a condition of debt relief. Some people feel that the increased number of students able to learn has put pressure on the education system and when combined with the MDG (Millennium Development Goals) this pressure can only lead to a crumbling of the system (Bunting 2012). The Millennium Development goals are a set of aims which were set out in an attempt to achieve the following: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger Achieve universal primary education Promote gender equality and empower women Reduce child mortality Improve maternal health Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases Ensure environmental sustainability Develop a global partnership for development (United Nations Development Programme 2012) 6 This study will also investigate the outside influences on Ugandan educational aims and policies to try and confirm if an outside interference is needed, useful or even welcomed by the people of Uganda. Education is widely considered to be a human right and so it is understandable that people would seek to provide education for everyone in Uganda, however, freedom of choice is also a human right so it must be questioned how much freedom of choice was given when these policy changes were made. Do the people of Uganda hold this kind of education in the same view we do, if not then what do they think and feel about it? I hope this study brings to light not only the current state of affairs regarding policy and practice, but also how the people of Uganda feel about this and whether or not something needs to be changed in order to facilitate their needs. I hope that this study will equip me with a stronger understanding of both the Piagetian theories on cognitive development and also the educational practices within Uganda. Through this study I would like to grow more confident in my ability to have a positive impact on the students I may one day have in Uganda by having a more in depth comprehension of what it is they need from their education and factors outside of the classroom which may be affecting their learning. Not only do I wish to discover whether or not Piaget has a place within the Ugandan classroom, I hope to find out if I have a place there either. As well as this I hope to test my own abilities to work independently, collect relevant materials from a wide source of information available and present my findings in an organised and coherent manner so that my studies can be used by others to further their knowledge in this area. I chose a topic which I 7 considered to be more ambitious in an attempt to push myself in my own learning and challenge myself to work harder to engage with a subject I have a strong interest in. It could be claimed that even this is in some way evidence of Piaget’s theory at work. Through my time at university I have learnt and experienced new things through facilitation by my tutors and peers and now it is my turn to attempt to turn my ‘area of work negotiated’ into my own research and experience in order to gain an understanding of my topic. Key terms within this study will be ‘cognitive development theory’ which refers to Piaget’s theory of how children learn, ‘stages of development’ which are the stages at which Piaget felt each level was reached and ‘accommodation and assimilation’ which is the process by which Piaget believed children learn – first acquiring knowledge/information and then through experience growing to understand it (Bartlett and Burton 2012, Piaget 1972, Barrelet, J.M and Perret-Clermont, A.N. 2008). The key organisations which may be referred to are UNESO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), UBOS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics) and USAID (United States Agency for International Development). I will also be using personal opinions from various sources as well as newspaper articles and the research of others. 8 Piaget – a literary overview Jean Piaget was born in Neuchâtel in Switzerland in 1896 and later attended the University of Neuchâtel in 1918 which was followed by a successful career in developmental psychology and genetic epistemology. His work has had quite a strong impact within the educational arena, though it is not without its criticisms (Barrelet and Perret-Clermont 2007). Throughout his work Piaget maintained that his ‘central aim has always been the search for the mechanisms of biological adaptation and the analysis and epistemological interpretation of that higher form of adaptation which manifests itself as scientific thought’ (Piaget 1977, p.xi). This pursuit of understanding of thought led to the creation of Piaget’s ‘cognitive development theory’ which was highly influenced by Kant’s constructivist model of knowledge but did have some differences (Bartlett and Burton 2000). Piaget believed that the growth of cognition relied on the child being driven by an internal need to understand the word. His theory was that maturation of the child’s learning coincides with the child’s experience of the world and therefore ‘progress through the sequence of discoveries occurs slowly and at any one age the child has a particular general view of the world, a particular logic or structure that dominates the way they explore and manipulate the world. (Bartlett and Burton 2000 p113). From this Piaget then created the concept of the ‘stages of cognitive development’: 9 Sensori-motor stage senses - learning is through physical action and the (0 to 2 years) Preoperational stage learning - now mental control guides actions and helps the (2 to 7 years) Concrete operational stage thinking - interest in explanation and using symbolic (7 to 11 years) Formal operations hypothetical - able to think abstract conceptions, logic, the (11+ years) (Bartlett and Burton 2000). Piaget’s ‘stages of development’ have been used in the past to assess a child’s level of cognitive ability and in some cases to diagnose if the child is in some way delayed in his or her development. While this can be useful for some children if they are experiencing a difficulty, many feel that assigning an age to the stages was unfair and did not take in to consideration outside factors, though these objections also had criticisms (Lourenco and Machad 1996). A key concept was the idea that new learning occurs through accommodation and assimilation of knowledge and experience: 10 (Pollard 2002) Piaget viewed the progression of the learner’s cognition as being linked to their own desire for growth. He felt that intellectual development was sequential to moral development and as one progressed so did the other as the learner moved through each stage. (Piaget, J. 1977) He believed that the process of ‘adaption’ led the learner through these stages as with each new experience and interaction with the world the learner would mature in their understanding. The strategies through which the learners adapted are referred to as ‘operations’. These were the new skills and mental activities used by the child to find the solution and could only be learned sequentially. For example, a child cannot learn to add or subtract without first learning to count. Piaget felt that at any one time a learner had a particular view of the world and only with experience could the learner realise the issues with their views and change it to become closer to the truth. (Bartlett and Burton 2000, p113). One test he did to show this was the three mountains test in which children were asked to describe what they could see and then switch point of view to 11 the opposite and again describe what they saw. This most children could achieve easily however when asked to describe what the person (doll) across from them could see they could not to as they were unable to imagine the view from someone else’s perspective. At this point the child is working within a particular schema (a cognitive framework or concept that helps organise and interpret information) which has certain characteristics about how the world works as discovered through the child’s experience of the world. As the child has only experienced the world from their own viewpoint and is a victim of ‘egocentric illusion’ (Donaldson 1978) it is difficult to imagine the scene from someone else’s perspective however if the child is able to acknowledge that there is a difference in the view from each side then they can change their logic to create a new schema and a new stage in their cognition can be reached. Thus the child has progressed there cognition through the process of assimilating information and changing their schema to accommodate this new change as a result of their new experience (Piaget 1970). http://www.cog.brown.edu/courses/cg63/images/3_mountains.gif 12 However one issue with this idea of assimilation and accommodation is the idea that age can be assigned to these experiences; it does not take into consideration individual differences, social context or modes of learning (Bartlett and Burton 2000, p114). It disregards the notion that each child has a different level of interaction with the world and therefore applying age related stages rather than experience labelled stages may be unjust to some children. This is in particular an issue when considering the education and cognitive development of children from different socio-economic and cultural back grounds. If one child does not receive information which they can assimilate and accommodate at the same stage as another are they to be considered any less able to achieve cognitive development? How can their life experiences be compared and analysed? (Donaldson 1978). Lourenco and Machad (1996) describe ten common criticisms of Piaget’s theory: 1. Piaget's Theory Underestimates the Competence of Children 2. Piaget's Theory Establishes Age Norms Discontinued by the Data 3. Piaget Characterizes Development Negatively 4. Piaget's Theory Is an Extreme Competence Theory 5. Piaget's Theory Neglects the Role of Social Factors in Development 6. Piaget's Theory Predicts Developmental Synchronies Not Corroborated by the Data 7. Piaget's Theory Describes but Does Not Explain 8. Piaget’s Theory Is Paradoxical Because It Assesses Thinking Through Language 9. Piaget's Theory Ignores Post-adolescence Development 10. Piaget's Theory Appeals to Inappropriate Models of Logic However their text titled ‘In Defense of Piaget's Theory: A Reply to 10 Common Criticisms’ then goes on to systematically defend Piaget’s work against each of these claims. They generally find the objections to Piaget’s 13 work are of a small nature or are due to a misunderstanding of the intentions and meanings of Piaget’s work. They tend to agree with Beilin that any view of Piaget’s work as being lacking is more due to a lack of understanding or research on the part of the critic rather than on Piaget’s part – it is "highly ironic that a number of otherwise astute investigators, in a short-sighted view of our history, have faulted Piaget for underestimating the cognitive competencies of young children" (Beilin 1992, p202). Other criticisms include critiques of the methodology used in Piaget’s research e.g. dissatisfaction with the sample size, lack of empirical analysis and issues with the tests which are used at each stage. However it could be argued that Piaget saw this methodology as appropriate for his time; he never claimed that his theories were universal and could be applied to every child’s cognitive development, only those involved in his research and others like them (Sutton-Smith 1966). Since Piaget conducted his original tests many others have carried out similar studies, though in some ways varied, and the majority have mostly concurred with his findings (Raven’s Coloured Progression Matrices, Otaala’s studies in Uganda and other repetitions of cognitive developmental exercises). Piaget did write on social interaction and its role in cognitive development, though he seemed to feel that it had little or no relevance because he believed that the most important source of cognition is the children themselves. Piaget emphasised the role of an inbuilt (biological) tendency to adapt to the environment, by a process of self-discovery and play and viewed the child as a ‘little scientist’. He argued that after initial input from an 14 adult or more knowledgeable other the child had to learn for themselves from their own desire to understand the world around them; this is a major way in which Piaget differed from other theorists. The table below shows the differences between the various theories on how children acquire knowledge and improve their cognitive development. The behaviourist view, as taken by theorist such as Pavlov and Skinner emphasises a focus on knowledge being passed down from the facilitator to the child. In this way children take a more passive role in their learning and are simply expected to absorb the information they are provided. The Constructivist approach and the Social Constructivist approach are similar in many ways as they believe children construct their cognition gradually through experience, the main difference being that constructivists such as Piaget believe in independent experience as being of predominate importance whereas Social Constructivists such as Vygotsky emphasise the importance of an adult or more knowledgeable other in the child’s progress through a more back and forward system of trying, feedback and trying once again. Vygotsky believes that language is a sign of early socialisation (Long, 2000) as language is a key skill picked up at a young age which suggests that being able to communicate is key to our lifestyle. An argument against this could be that communicating needs is essential, social communication is not necessarily a primary function of language. Vygotsky also emphasised the role of culture and experience because he believed that what drives cognitive development is social interaction – a child’s experience with other people. He claimed that it is culture which is needed to shape cognition which can be referred to as viewing the ‘child as 15 apprentice’ in contrast to Piaget’s view of the child as a ‘little scientist’. Piaget’s idea of accommodation and assimilation worked off the principle that cognitive development is a constructive process where individuals construct their own understanding through ‘…building up structures by structuring reality’ requiring very little feedback after the initial contact with the facilitator (Piaget, 1971, p.27). (POLLARD 1990) Evaluation of both the constructivist and behaviourist approaches would suggest that a constructivist approach is most productive as it allows learners to have a more active role in their own learning rather than simply memorising information, however whether or not they learn better through the ‘active individual’ or ‘active social’ is still debatable. In current educational practices in the UK examples of all three of these approaches 16 can be seen in the way learners are taught. In primary school students are often taught the alphabet and basic mathematics through a behaviourist approach of repetition and memorising however once these basic skills have been learnt they are more able to be creative with their new knowledge and investigate it independently (little scientists/ active individual) or through trial and error with facilitator feedback (little apprentice/ active social). This would suggest that all three approaches have some validity in enabling the cognitive development of learners, although the presence of classroom practices such as ‘circle time’ do seem to suggest that importance is placed upon the role of social interaction as ‘quality circle time provides the group listening system for enhancing self esteem, promoting moral values, enhancing social skills and building teamwork’ (Mosely 2005). This also takes the emphasis off mere academic learning and focuses on other skills learned within an educational setting such as social skills, moral code and self-awareness. Can these things be taught through a behaviourist approach? Overall though Piaget’s theories do have their criticisms they seem to be most useful when considering how children should be taught and the only valid objection to be made is the concern expressed over learners who are left to their own devices without experiencing enough help in the ‘area of work and activity negotiated’ stage of learning and their lack of understanding is unnoticed for some time they will be at a strong disadvantage. However it can also be noted that an overbearing facilitator is a risk with Vygotsky’s ‘little apprentice’ approach and this could easily turn into a behaviourist method in which the learner is merely passively receiving 17 information. As long as it is thoroughly checked that the child has been given accurate assistance and information at the start of their attempt to progress a Piagetian approach is the most suitable to encourage a child to learn for themselves as it creates the desire to learn which will assist the child to become an independent learner and look beyond the information they are provided. 18 Ugandan History and Education – a literary review To consider the educational history and practices of Uganda one must first define what is ‘education’ and what is the difference between policies and practices. Education is the process by which information and skills are passed from one person (a more knowledgeable other or a facilitator) to another lesser knowledgeable learner (Bartlett and Burton 2000). These skills and pieces of information take many forms and are generally believed to be of importance to the learner’s life and cognitive development. Educational policy is the term used to refer to the guidelines and rules which are set out by an authoritative organisation, usually the government, which control or monitor the practices and progress of education. Uganda has a decentralized system of governance and several functions have been ceded to the local governments. However, 'the central government retains the role of making policy, setting standards, and supervising' (Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006, p1). The ‘practice of education’ refers to the manner in which the teachers or facilitators impart knowledge to the learners. The difference between this and policy is that while policy can cover the monetary/financial and academic achievement standards the practice refers only to the manner in which the students are taught (usually based on work by educational theorist e.g. Piaget, Vygotsky, Skinner). 19 The system of education in Uganda has a structure of 7 years of primary education,6 years of secondary education (divided into 4 years of lower secondary and 2 years of upper secondary school), and 3 to 5 years of postsecondary education (Pascal Al Amin 2012). IN 1997 the UPE act – Universal Primary Education Act meant that for four children in every family primary education would be provided for free. While this did lead to an increase in the number of students attending primary education it was also found that the system would need many improvements in order to be able to provide for its pupils at upper levels. ‘The central conclusion of the multilevel analysis was that equality of access to formal primary education did not necessarily translate to equality of outcomes’ (Leibbrandt and Zuze 2010). People from lower socio-economic backgrounds are still struggling to pay for the added necessities that accompany an education such as uniform and books or other provisions. This is particularly an issue for families with higher numbers of children as other than through passing down of clothes and provisions there are few ways they can save on the cost of education in order to be able to send all of their children to school – ‘because of the narrow definition of free education, households were still required to make substantial contributions to schooling’ (Leibbrandt and Zuze 2010). In addition to this, the 2005 MOES report showed that the number of teachers and schools increased by 41% while the student number increased by 171% between 1997 and 2004. This shows that the percentage of students increased by over four times the percentage of teachers and suggests that this could mean teachers were then attempting to teach up to four times more students. Some classes class sizes go up to seventy pupils 20 and more per classroom, most especially in lower classes (Nakabugo Et Al 2008) where ‘class sizes grew to over 100’(Buczkiewiczand Carnegie 2000) compared to classes in England which are classified as being ‘large’ if they have above 25-30 students (Smith & Warburton 1997). Problems for teachers can be issues of management, lack of flexibility and student diversity. For the students the issues experienced could be related to minimum teacher attention and access to materials, hesitation to ask questions and the need for individual effort challenge the students (Ives 2000). If students feel that the teacher is not giving them the attention they deserve, or alternatively if students feel the lack of attention they are given means they do not need to try hard, then this could discourage students from putting in the effort required for satisfactory learning. Research shows that classes smaller than 20 in the early years of primary school lead to improved performance. However, this number is not realistic in developing countries and is even beyond the resources of some industrialised countries (O’Sullivan 2005), This suggests that it is not simply enough to provide the access to education but also the government needs to work on ensuring that the level of education provided is adequate to provide the students with a basic education that will be enough to get them into the next stage of learning, whether that is more studies or life skills. Studies have shown that educational level is strongly associated with contraceptive use, fertility, and the general health status, morbidity, and mortality of children (Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006, p23). 21 Another possible issue with the UPE scheme is the manner in which the grants are awarded. Currently the grants are given to each primary school based on how many pupils it has. This could possibly encourage schools to take on high levels of students or even to hold students back in order to receive maximum funding and salary for the teachers. While there is no evidence that this has been an incentive for schools as of yet, the possibility remains and therefore it might be advisable to modify the funding to avoid this (Nishimura, Takashi and Sasaoka 2006). In particular those who are struggling to receive an adequate education are those in rural areas. Often children will need to walk great distances to get to and from school, as well as having domestic responsibilities whilst at home. This can tire out the students and discourage some from attending. As well as this some families may need their children to assist with the care of other children or work around the home/farm (Mutonyi and Norton 2007. Most policies and curriculum materials in Uganda view educational communities as homogeneous groups and do not take into account the social and political histories of different local settings, particularly with respect to discrepancies between rural and urban settings (Mutonyi and Norton 2007, p 267). Despite the recent changes in policy and the efforts to increase attendance and education in primary aged students there are still many children who do not make it to school at age six. There are more males then females amongst those who have never been to school; nearly one in four females (23%) age six years or older in Uganda has never been to school, compared with 12%of males (Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006, p23). Many of these children do not attend in the rural areas due to the reasons 22 listed above. To counter this the government needs to make more changes such as providing more local schools or improving the parental awareness of the importance of a good education so that they are more inclined to encourage their children to attend. Uganda, like many countries in the developing world, faces enormous challenges of poverty, political instability, gender inequities and HIV/AIDS. In 2001, the population below the poverty line was estimated at 35%, and the literacy rate was approximately 70%, with males at 80% and females at 60% (UBOS, 2002). The Ministry of Education and Sports has begun efforts to pay special attention to schools in the “ hard-to-reach” areas, they have topped-up salary and improved the provision of housing for teachers; though internal inefficiency, such as delayed enrolment and repetition, remains a major problem in primary education (Nishimura, Takashi and Sasaoka 2006). Ugandan education could also be suffering due to a lack of technology which many classrooms in better-developed countries make use of in every day teaching. Whilst 14% of the world’s population was using the Internet by 2004, over half the population in developed regions had access to the Internet, compared to 7% in developing countries and less than 1% in the 50 ‘least developed countries’ (UNDESA, 2006). This lack of access to internet information could be reducing the productivity of teaching and a plan to initiate more internet involvement in Uganda would be advisable, particularly as outside of developing countries the internet and computers are used for almost all aspects of work and life. 23 The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda 1995 promotes the notion of education as being a basic human right and the government’s requirement to facilitate this in the following statements: All Ugandans enjoy rights and opportunities and access to education, health services, clean and safe water, work, decent shelter, adequate clothing, food security and pension and retirement benefits. (p16 ) The State shall promote free and compulsory basic education. The State shall take appropriate measures to afford every citizen equal opportunity to attain the highest educational standard possible. Individuals, religious bodies and other nongovernmental organisations shall be free to found and operate educational institutions if they comply with the general educational policy of the country and maintain national standards.( P17) 30. Right to education - All persons have a right to education (p31) Whilst these notions are admirable some Ugandan people feel that the changes made to enable free primary education were unjustly forced upon them as a condition of debt relief. Some feel that the increased number of students able to learn has put pressure on the education system and when combined with the MDG (Millennium Development Goals – a list of eight key goals which need to be met) this pressure can only lead to a crumbling of the system (Bunting 2012). This can be compared with the UK governments insistence on achieving higher GCSE’s pushing teachers to focus more on grade-achievements than the actual learning or the government’s aims to have 50% of students reach Higher Education without creating enough spaces for them. Policies created simply for the effect of looking good on government agendas are not for the best of the people the government is supposedly trying to help. In Uganda only 35% of post-secondary pupils are able to secure a place at university due to the lack of universities. Makerere University takes on 95% of all university students whilst the remaining 5% 24 are left to find places at smaller universities leaving 65% of post-secondary students looking for alternative options (EdUniversalRanking 1999). Overall, whilst the Ugandan government has done well to increase access to education at primary levels it needs to focus on ensuring this education is of a good standard and that students are provided with the opportunity to progress to secondary and post-secondary education. 25 Applying Piaget to Ugandan Education For this section it will be assumed that the issues outlined in the previous section will have been rectified and that the only concern for education is the manner in which the students are taught. To begin with one must question why there is any need for any form of theory to be applied to the classroom, surely the important thing in the classroom is for the children to be given information to learn so they can do well in exams and progress there education. Piaget would argue against this and suggest that an education system which focuses only on results is not correctly supporting its learners. He feels that children should be encouraged to learn by creating within them a desire for knowledge. This will enable them to continue to learn and grow cognitively even outside the classroom or after their time with education has passed. ‘There are two places we can look for ideas about education. One is the future: what kind of world are today’s young people going to inhabit; and what skills and qualities will they need to thrive therein? And the second source of practical inspiration is theory: what are the best ideas available about the potentialities of the human mind and spirit, and about how minds and spirits grow?’ (Wells & Claxton 2002, p1). Piaget’s concern with the mechanisms of biological adaptation and the higher form of scientific thought, the epistemological interpretation being his focus, meant that he was not simply concerned with finding the best way to enable learners to progress, but also with how and why they progress and 26 the effects this can have on them after they leave the learning arena. (Piaget 1977) He wished to create learners which were ‘little scientists’ and who were led by their own desire to learn rather than students who were made to learn in order to achieve grades (Alexander and Potter 2005). In relation to Uganda this approach could be of much use to the students due to the large class numbers and the common lack of an educated sibling or parent to encourage the learning. In these situations the students must strive to learn from their own desires for knowledge and not because they are told to. In Uganda there is a particular issue with more educated elders as during the 20 year tirade of war and destruction by Joseph Kony many of the Ugandan people neglected their education to focus on things which were deemed more important such as staying safe or fighting. This unfortunately led to a generation which had many uneducated members who could either not understand their children’s learning or came to view it as unimportant which led to a lack of support for the learners. For this reason encouraging independent learning is crucial to maintaining the learners focus on their education. Whilst it could be said that those who missed out on education in Uganda have found other ways to lead productive lives the Dakar 2000 demand for Education for All by 2015 is based on the premise that education is a human right that enables people to improve their lives and transform their societies (UNESCO, 2000, p8). This is not the same as claiming that education should be mandatory for all, but instead states that having access to education can not only improve the learner’s cognitive growth but can help them in areas of 27 their lives outside of the classroom and thus improve their lifestyles and the state of the society. Using Piaget’s theory in Uganda allows for us to draw comparisons between them and ourselves; a theory can allow us to find similarities and differences across different learning contexts– e.g. sitting in a lecture theatre at university and sitting on the carpet in a primary classroom or even sitting outside underneath a tree as many classes in Uganda still do. It allows us to consider the importance of the various roles within the classroom; those of the learners, of the teachers, of the peers and of those outside the classroom who create the policies. It is important when thinking about the notions of assimilation and accommodation to progress cognitive development that we realise that we do not need to learn the same subject matter, as long as we learn the function of adjusting our schemata whenever we realise there is a change to be made the fundamental processes will be picked up and we will progress - ‘if something is interesting you learn very quickly, if you are bored you hardly learn anything’ (Alexander and Potter, 2005). There is no reason to insist that learners have to experience the same things or be taught the same subjects in order to progress cognitively, therefore Piaget’s theories of cognitive development can be considered to be universal as long as learners are progressing through their own ambitions to learn. When considering the motivation for Ugandan citizens to focus their attention and resources on their education it is important to consider how important to their day to day lives they consider an education to be, As stated before many Ugandan people said they felt the changes to the education system had been forced upon them (Bunting 2012) and this is supported further by 28 the research of ..... which found that education came sixth in a list of factors which the Ugandan people felt it was important for their government to be focusing on. By viewing these results it is quite clear that Maslow’s theory of the ‘hierarchy of needs’ comes into play significantly. The Mosby Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, & Health Professions 8th Ed describes Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs as being ‘a hierarchic categorization of the basic needs of humans’. On the base level the most basic of needs are met such as those required for the physical needs of the body – the biological or physiological needs; these include the necessities for the continuation of life such as air, food and water. Next is the need to live safely with shelter and protection from fear and anxiety. Following this are the needs felt for the desire to ‘belong’ – to feel love, followed by the need for self esteem and finally a desire for self-actualisation. To get from one stage to the next the basic needs must first be satisfied. One cannot reach selfactualisation if they are unfed, unsheltered and have no self-esteem. (Huitt, W. 2007) 29 The prioritising of needs such as food, housing and safety over education means that currently many people in Uganda feel that they are still struggling to find their needs met on even the basic needs in Maslow’s hierarchy – ‘physiological’ and ‘safety’. Maslow states that these are the basic and most prioritised needs so until these needs are met there will be little or no desire for the feelings of belonging, esteem or self-actualisation that a structured educational environment might provide (Maslow 1999). Finally one must consider again the definition of education and learning. If education is the passing down of knowledge from a facilitator/more knowledgeable other to the learner and the learning is the picking up of this information or skill then surely it is restrictive to classify this as being something which must take place within a classroom environment. Piaget’s theory applies only to the manner in which learners acquire cognitive development; he does not specify the topic of learning or even the manner of learning (auditory, written, practical) and therefore as long as the children of Uganda continue to experience new things and adapt their schemata to assimilate to the new information they have received in order to accommodate it then surely their cognitive development will progress regardless of the setting. Right now until the needs of the Ugandan people are met on Maslow’s most basic level of the hierarchy of needs then the focus in Uganda, or at least the focus of the people of Uganda, regardless of government policy will be on 30 learning life-skills which will aid them in securing the basic necessities in order to have the luxury of seeking goals higher up the hierarchy. These lifeskills can be defined in many ways, Buczkiewiczand Carnegie (2000) described them as ‘a range of psycho-social competencies such as decision making, problem solving, critical and creative thinking, communication and interpersonal skills, empathy and self-awareness, and coping with stress and emotion’ which is a useful psychological viewpoint of the life skills required but also these can be described in more practical terms as the skills and knowledge required to provide the basic levels of need; the knowledge of how to build shelter, find or hunt food and stay safe from danger. Ultimately, as the saying goes: ‘Give a man a fish and he will eat for a day, teach a man to fish and he will eat for a life time’ (Unknown Source) As long as people are taking the constructivist approach of learning and ‘doing’ for themselves rather than the behaviourist approach of being ‘force fed’ information then Piaget is relevant. 31 Conclusion Engaging in this study brought the realisation that there are far more issues surrounding the application of theory into practice than simply ‘can it be applied?’ - One must also consider ‘should it be applied?’ Firstly from this study the question was raised whether or not the theories of Piaget are worthy of being used as a basis for educational policy decisions in any country, not just Uganda specifically. There are many critiques of Piaget’s work but mostly these apply to his manner in which he carried out his studies or the application of age barriers, not the logic in his theories. This was in some ways recovered by other theorists repeating his tests with different groups of children in more controlled settings to establish the validity of his work. In the majority it was found that further attempts to research and document the ‘stages of cognitive development’ agreed with Piaget’s initial findings (Otaala, Raven). Although some may still disagree with the use of age brackets in the ‘stages of development’ it has been found repeatedly that the majority of children will fall inside Piaget’s guidelines and arguments for changing them have had little or no premise on which to prove they are inaccurate. It was interesting to compare the constructivist theories of Piaget against the opposing behaviourist theories of people such as Skinner as I found that I was able to consider both points of view and come to my own conclusion about which I most found myself agreeing with. I discovered through this 32 study that I am inclined towards a Constructivist approach to cognitive development although my personal approach would be a mixture of active individual and active social. Secondly the concerns over the ‘life experience’ of the child affecting the progression of their cognitive development were also in some ways eradicated; through thorough examining of the criteria Piaget outlined in his theories it became evident that the experiences of the child could be varied as long as they were able to realise new things and change apply changes to their schemata at various points they would progress cognitively; they did not need to all experience the same events, merely they needed to experience life to learn that their original preconceptions and ideas about how the world worked might be flawed and in need of change. Previous to this study I had assumed that without a firm educational structure similar to that which we have in the UK Piaget’s stages could not be reached at a similar time in Uganda, however Otaala’s study showed that even without preschool or any formal learning the Ugandan children 6+ were on similar levels with Piaget’s ‘stages of development’ showing that it is experience of life, not experience of the classroom, which allows learners to move through the stages of cognition and become more able learners - they simply learnt about things more relevant to their lifestyles. I was surprised to learn that many of Piaget’s theories have already been taken into consideration within Ugandan schools; some schools were actually named after Piaget such as the Piaget Junior School. This highlighted another point about Western involvement in Ugandan education; if there is to be involvement then the outside parties wishing to become 33 involved should ensure that they educate themselves appropriately before heading into the classroom environment and initiating any changes. Had I gone to Uganda prior to this study I would have had preconceived notions of a nation in need of my ‘Western expertise’ and theoretical knowledge about education; I assumed that they would not have already established Piagetian based policies simply because of their tumultuous history. I believe that in this case I was suffering from my own state of egocentric illusion and could only view the situation in Uganda from my own outside perspective using my preconceptions to imagine what the situation would be inside Uganda instead of researching it. This study has illuminated many facts and abolished many untrue presumptions held prior to the investigation. In regards to the current educational practices in Uganda the study found that in the last two decades much effort has been put into improving the access to and standard of education provided. However it was noted that the attempts to improve access to education had several flaws which predominately led to issues with the quality of education provided. This relates directly into the notion of Piaget’s ‘little scientist’ because although Piaget does claim that children learn best independently he also acknowledges the necessity for an original input from a facilitator and in classes of 40-80 students this input could be lacking and the learner may be unable to progress. Certainly in Vygotsky’s eyes these standards would be unacceptable as the children would not be receiving enough guidance and input to allow them to be ‘little apprentices’, unless this input was given by an older more knowledgeable student. 34 Therefore it seems that the notion of applying Piaget’s constructivist theories on cognitive development is valid, however it would seem the issue is not ‘are the theories applicable?’ but rather ‘can they be applied?’ - meaning is the current level of educational provision in Uganda, particularly in its more struggling rural areas, adequate enough that teachers are able to apply his work to their teaching styles or are they likely to be swamped with high class numbers and distracted by poor living agreements. Currently the Ugandan government is working to improve conditions for both students and teachers by improving the number of schools and increasing the standard of pay and living situations for teachers. As well as this the government is aiming to improve teacher training and better equip the teachers to facilitate the learning of their students. Hopefully once these changes are complete Ugandan’s ‘little scientists’ will be able to receive an education which will enable them not only to do well in primary school but also to desire to learn and continue on through secondary school and possibly post-secondary, although there are issues also with secondary and post-secondary education which will need to be addressed. If I were able to extend this study I would like to extend it to include other countries throughout the world. In particular I am intrigued by the concept of looking at education in countries with more rigorous governmental controls and less focus on the individual such as Soviet Russia or China – does the level of governmental control affect the manner in which education is provided and does this then have a knock on effect to how children learn. Even within England it is possible to see where inappropriate teaching styles can leave children without an ability to learn for themselves; I would be 35 interested to know if any other countries still have a routine within classrooms that is so vigorously regimented and monitored that children are force-fed information to achieve results rather than encouraged to learn independently for the sake of learning. In contrast to this I would also like to look at countries were independent learning is more strongly encouraged than in the UK such as in Sweden or Norway. These pupils reportedly gain high levels of attainment in exams – could this be said to be attributed to Piaget’s theories of assimilation and accommodation? Is it better to encourage children to learn more independently and have the learning facilitators take a more back ground role in children’s’ educations? As well as this I would like to branch out the study into investigating the problem of preconceived notions held by different countries about each other. Should there be a stronger attempt to teach students about other cultures and the history of other countries. It may be possible to discover these things in particular subjects such as history or social studies but should more emphasis be placed in main subject areas to allow for the widening of knowledge about other cultures to remove the sense of ‘otherness’ we feel about countries we have not visited and their people? Or is this kind of progress not conducive to achieving high attainment in the core subjects so therefore deemed unnecessary? I would argue that broadening students’ knowledge of the world is an important factor of their education, particularly now that the world has become more of a global concept and it is much more common to experience life in other countries due to the ease of travel. Students should be taught about the world as a whole in order to make them functioning members of this wider community. It is no longer simply a case of 36 understanding your own culture and nationality; in an ever changing world which is constantly creating opportunities for travel and relations with other countries it is arguable that people should be learning more about the lifestyles of their peers in other countries. 37 References Alexander, J. and Potter, J. (2005) Education for a change – listen to students. Abingdon : Rentledge Falmer. Barrelet, J.M and Perret-Clermont, A.N. (2008) Jean Piaget and Neuchâtel: The Learner and the Scholar. East Sussex: Psychology Press. Bartlett,S. and Burton, D. (2000) Introduction to Education Studies: 2nd Ed. London: Sage. Beilin, H. (1992). Piaget's enduring contribution to developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 28, 191-204. Buczkiewicz, M and Carnegie, R. (2001) The Ugandan Life Skills Initiative. Health Education, Vol. 101 Iss: 1, pp.15 – 22. Online: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/10.1108/09654280110365190 [Accessed 18/03/2012] Bunting, M. (2008) Debate: the state of education in Uganda. http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/katineblog/2008/may/23/ugandawillachiev eitsmillen [accessed 20/02/2012] Claxton, G. And Wells, G (2002). Learning for life in the 21st century. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. National Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy: Arrangement of Objectives. http://www.justice.go.ug/docs/constitution_1995.pdf [accessed 18/03/2012] Donaldson, M. (1978) Children’s Minds. London, Fontana. EdUniversal Ranking (1999). Business, School and University Ranking in Uganda. http://www.eduniversal-ranking.com/business-school-universityranking-in-uganda.html [Accessed 20/03/2012] IMDB. (2011) Machine Gun Preacher. IMDB online. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1586752/ [accessed 28/02/2012] Invisible Children (2012). Kony 2012. http://www.kony2012.com/ [accessed 08/03/2012] Ives, S. M. (2000). A survival handbook for teaching large classes. Center for Teaching & Learning. UNC Charloote. Online: Division of Academic Affairs http://teaching.uncc.edu/articles-books/best-practice-articles/largeclasses/handbook-large-classes [Accessed 19/03/2012] 38 Huitt, W. (2007). Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Online: http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/conation/maslow.html [Accessed 14/03/2012] Jelmert Jorgensen, J. (1981) Uganda: A Modern History. London: Croom Helm Ltd. Kaguire, R and Smith, D. (2012) Kony 2012 video screening met with anger in northern Uganda. The Guardian Online. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/mar/14/kony-2012-screening-angernorthern-uganda [Accessed: 15/03/2012] Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential learning. London: Prentice Hall. Leibbrandt, M. and Zuze, T.L. (2010) Free education and social inequality in Ugandan primary schools: A step backward or a step in the right direction? International Journal of Educational Development: ElseVier. Vol31. 2, p169– 178. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.013 [Accessed 20/03/2012] Long, M. (2000) The psychology of Education. Oxon: Routledge Falmer. Lourenco, O. And Machad, A. (1996). In Defense of Piaget's Theory: A Reply to 10 Common Criticisms. Psychological Review. American Psychological Association. 103:1, p143-164. Online: http://cohort09devpsyc.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2010/01/Lourenco_1999. pdf [Accessed 18/03/2012] Maslow, A. (1999) Toward a Psychology of Being. 3rd Ed. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. Ministry of Education and Sport for the Republic of Uganda. (2007) 4th edition of the education and sports sector annual performance report (ESSAPR). Ministry of Education and Sports, MoES. Ministry of Education and Sport for the Republic of Uganda. http://www.education.go.ug/ [Accessed 23/02/2012] Mosby (2008) Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Mosby's Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, & Health Professions 8th Ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences. Mosely, J. (2005) Transforming the way we teach our children – self esteem and motivation. Oxon: Routledge Falmer. Mutonyi, H. and Norton, H. (2007) ICT on the Margins: Lessons for Ugandan Education http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.2167/le751.0 [Accessed 18/03/2012] 39 Mwamwenda, T.S. (1992) Cognitive Development in African Children. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, Vol. 118, 1992. http://www.questia.com/googleScholar.qst?docId=95180914 [Accessed 05/10/2011] Nakabugo Et Al (2008) Large Class Teaching in Resource-Constrained Contexts: Lessons from Reflective Research in Ugandan Primary Schools. CICE Hiroshima University, Journal of International Cooperation in Education.11.3, 85-102. Online: http://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/cice/113nakabugo.pdf [Accessed 23/03/2012] Nishimura, M., Takashi, Y and Sasaoka, Y. (2006). Impacts of the universal primary education policy on educational attainment and private costs in rural Uganda. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738059306001192 [Accessed 22/03/2012] O’Sullivan, M (2005) Teaching large classes: The international evidence and a discussion of some good practice in Ugandan primary schools. International Journal of Educational Development. 26.1, 24–37. Online: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.05.010 [Accessed 19/03/2012] Pascal Al Amin, O. (2012) Review of education policy in Uganda. Slideshare.net. http://www.slideshare.net/ojijop/review-of-education-policy-inuganda [Accessed 28/02/2012] Piaget, J. (1971) Science of education and the psychology of the child. New York: Viking Press Piaget, J. (1972). The psychology of the child. New York: Basic Books. Piaget, J. (1977) H.E.Gruber & J.Voné che (Eds). The Essential Piaget. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Pollard, A (1990) Learning in Primary Schools. Cassell, London Pollard, A. (2002) Readings for Reflective Teaching. London: Continuum Satterly, D. (1987) "Piaget and Education" in R L Gregory (ed.) The Oxford Companion to the Mind Oxford, Oxford University Press Smith, P. & Warburton, M. (1997). Strategies for managing large classes: a case study. British Journal of In-service Education, 23, 253-266. Sutton-Smith, B. Psychological Review: Piaget on play: A critique. Vol 73(1), Jan 1966, 104-110. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) (2002).Uganda DHS EDU Data Survey, 2001. Kampala:UBOS. 40 United Nations Development Programme. (2012) Millennium Development Goals. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/mdgoverview.html [Accessed 23/03/2012] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2000) The Dakar framework for action. Education For All: Meeting our collective commitments. Paris: UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001211/121147e.pdf [ Accessed 18/03/2012] United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (2006) ICT for Teacher Professional Development in Uganda. Impact and Scalability Assessment. Centre for Applied technology: Dot.Com documents, USAID. Wood, D. (1998) How children think and learn – 2nd Ed. London: Blackwell Publishing. 41