Civil Procedure II – Smith – Spring 2012

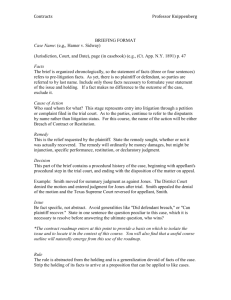

advertisement