Theoretical Concerns Versus Clinical Knowledge and Applications

advertisement

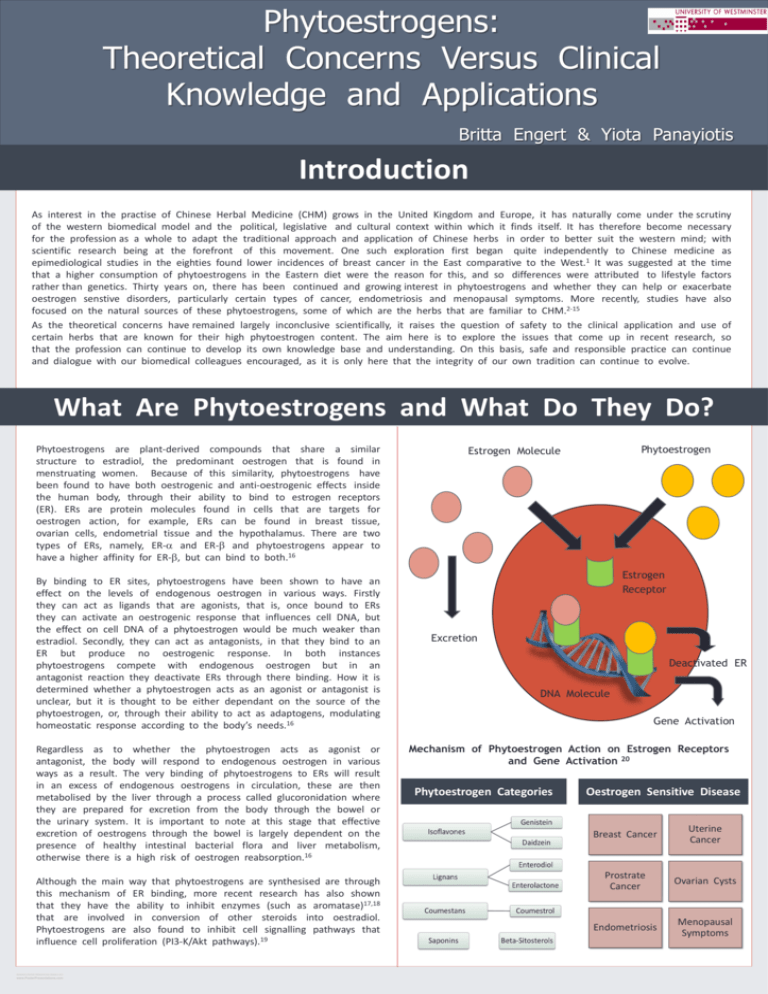

Phytoestrogens: Theoretical Concerns Versus Clinical Knowledge and Applications Britta Engert & Yiota Panayiotis Introduction As interest in the practise of Chinese Herbal Medicine (CHM) grows in the United Kingdom and Europe, it has naturally come under the scrutiny of the western biomedical model and the political, legislative and cultural context within which it finds itself. It has therefore become necessary for the profession as a whole to adapt the traditional approach and application of Chinese herbs in order to better suit the western mind; with scientific research being at the forefront of this movement. One such exploration first began quite independently to Chinese medicine as epimediological studies in the eighties found lower incidences of breast cancer in the East comparative to the West.1 It was suggested at the time that a higher consumption of phytoestrogens in the Eastern diet were the reason for this, and so differences were attributed to lifestyle factors rather than genetics. Thirty years on, there has been continued and growing interest in phytoestrogens and whether they can help or exacerbate oestrogen senstive disorders, particularly certain types of cancer, endometriosis and menopausal symptoms. More recently, studies have also focused on the natural sources of these phytoestrogens, some of which are the herbs that are familiar to CHM.2-15 As the theoretical concerns have remained largely inconclusive scientifically, it raises the question of safety to the clinical application and use of certain herbs that are known for their high phytoestrogen content. The aim here is to explore the issues that come up in recent research, so that the profession can continue to develop its own knowledge base and understanding. On this basis, safe and responsible practice can continue and dialogue with our biomedical colleagues encouraged, as it is only here that the integrity of our own tradition can continue to evolve. What Are Phytoestrogens and What Do They Do? Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds that share a similar structure to estradiol, the predominant oestrogen that is found in menstruating women. Because of this similarity, phytoestrogens have been found to have both oestrogenic and anti-oestrogenic effects inside the human body, through their ability to bind to estrogen receptors (ER). ERs are protein molecules found in cells that are targets for oestrogen action, for example, ERs can be found in breast tissue, ovarian cells, endometrial tissue and the hypothalamus. There are two types of ERs, namely, ER-a and ER-b and phytoestrogens appear to have a higher affinity for ER-b, but can bind to both.16 By binding to ER sites, phytoestrogens have been shown to have an effect on the levels of endogenous oestrogen in various ways. Firstly they can act as ligands that are agonists, that is, once bound to ERs they can activate an oestrogenic response that influences cell DNA, but the effect on cell DNA of a phytoestrogen would be much weaker than estradiol. Secondly, they can act as antagonists, in that they bind to an ER but produce no oestrogenic response. In both instances phytoestrogens compete with endogenous oestrogen but in an antagonist reaction they deactivate ERs through there binding. How it is determined whether a phytoestrogen acts as an agonist or antagonist is unclear, but it is thought to be either dependant on the source of the phytoestrogen, or, through their ability to act as adaptogens, modulating homeostatic response according to the body’s needs.16 Regardless as to whether the phytoestrogen acts as agonist or antagonist, the body will respond to endogenous oestrogen in various ways as a result. The very binding of phytoestrogens to ERs will result in an excess of endogenous oestrogens in circulation, these are then metabolised by the liver through a process called glucoronidation where they are prepared for excretion from the body through the bowel or the urinary system. It is important to note at this stage that effective excretion of oestrogens through the bowel is largely dependent on the presence of healthy intestinal bacterial flora and liver metabolism, otherwise there is a high risk of oestrogen reabsorption.16 Although the main way that phytoestrogens are synthesised are through this mechanism of ER binding, more recent research has also shown that they have the ability to inhibit enzymes (such as aromatase)17,18 that are involved in conversion of other steroids into oestradiol. Phytoestrogens are also found to inhibit cell signalling pathways that influence cell proliferation (PI3-K/Akt pathways).19 RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2011 www.PosterPresentations.com Phytoestrogen Estrogen Molecule Estrogen Receptor Excretion Deactivated ER DNA Molecule Gene Activation Mechanism of Phytoestrogen Action on Estrogen Receptors and Gene Activation 20 Phytoestrogen Categories Oestrogen Sensitive Disease Breast Cancer Uterine Cancer Prostrate Cancer Ovarian Cysts Endometriosis Menopausal Symptoms Phytoestrogens: Theoretical Concerns Versus Clinical Knowledge and Applications Britta Engert & Yiota Panayiotis Phytoestrogenic Components of Chinese Herbs In Vivo Studies 21-23 Dan Dou Chi Dang Gui Gan Cao Semen sojae preparatum Angelica sinensis radix Gycyrhizzae radix Isoflavones Isoflavones Isoflavones Coumestans Coumestans Coumestans Lignans Saponins Gan Jiang Sheng Ma Zingiberis rhizoma Cimicifuga racemosa Beta-Sitosterol Isoflavones Isoflavones Coumestans Coumestans Study name Study Design Interventions Participant Study Length Outcome Measures Results Hirata et al, 1997 2 Double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Dang gui vs placebo 71 Postmenopausal women 24 weeks 1)Endometrial thickness 2) Vaginal cell maturation 3) Vasomotor flushes No difference between treatment and placebo group Quella et al, 2000 3 Double- blind, randomized, placebocontrolled Soy tablets vs placebo 177 Breast cancer survivors 4 weeks Hot flashes Soy not more effective than placebo Davis et al, 2001 4 Double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled CHM vs placebo Vasomotor symptoms CHM was no more effective than placebo Ziegler, 2004 24 Epidemiological Study Intake of phytoestrogens (lignans and isoflavones ) 15000 Dutch women 8 Years Newton et al, 2006 5 Double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Black cohosh vs black cohosh + multi botanical vs multiBotanical + soy vs estrogens vs placebo 351 peri- or postmenopausal women Kwee et al. 2007 6 Double- blind, randomised placebocontrolled CHM vs HRT vs placebo 31 Dutch women Ge Gen Puerariae radix Lignans Huang Qi Ren Shen Shao Yao Astragalus membranacus Ginseng radix Paeonia lactiflora Beta-SitoSterol Beta-Sitosterol Beta-Sitosterol Saponins Saponins 55 12 weeks postmenopausal Australian women 1) Phyto-estrogen intake 2) Breast cancer rate No association between phyto-estrogen intake and breast cancer 12 month Vasomotor symptoms 1) Herbal intervention not different from placebo 2) Hormone therapy superior to placebo 16 weeks Vasomotor symptoms 1) HRT most effective 2) CHM more effective than placebo Rotem and Kaplan, 2007 7 Double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phyto-Complex 50 (black cohosh, pre and dang gui, milk postmenopausal thistle, red clover, women, aged American ginseng, 44–65 years chaste-tree berry) vs placebo 3 month Menopausal symptoms Phyto-Complex significantly higher reduction in menopausal symptoms to placebo D’Anna, 2009 25 Double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Genistein vs placebo n=389 24 months Hot flushes Endometrial thickness 1) Genistein reduces hot flushes 2) No difference in endometrial thickness Lipovac, 2011 8 Double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled cross over Red clover Vs placebo Postmenopausal women 187 days Mucosal status Libido Tiredness Moods Subjective improvement of all symptoms with Red clover extract Deng et al, 2012 9 Multicenter follow-up study Fufang vs placebo 194 postmenopausal women (47– 70 years old) 5 years Potential adverse events and fracture incidence Fracture incidence 2.4 fold lower in the treatment group than placebo Summary of Results Ku Shen Mo Yao Pu Gong Ying Sophorae flavenscentis radix Commiphora myrrha Taraxacum officinale Isoflavones Beta-Sitosterol Beta-Sitosterol Clinical research into the use of herbs with phytoestrogen components in patients at risk of, or with, oestrogen sensitive cancers is limited. Current evidence, which is mostly epidemiological, would not support any effect of phytoestrogens, neither positive nor negative. However, only reports in the English language have been reviewed. There may be a significant body of research reported in Chinese or Japanese language, which could not be accessed. Research into the use of CHM with phytoestrogens for menopause related symptoms would suggest good safety and efficacy for herbs in the treatment of mild symptoms, however for moderate or severe cases classic HRT is clearly more effective.5,6,7,8,9,25 Huai Hua Xi Yang Shen Sheng Di Huang Sophorae flos Panax quinquefolium Rehmannia radix Isoflavones Beta-Sitosterol Beta-Sitosterol Saponins RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2011 www.PosterPresentations.com The design of almost all clinical studies does not take into account the theory and practice of classical CHM, but applies them in isolation from their usual formulas, sometimes even only using components of single herbs, for short time frames, and outside the classical CHM diagnostic framework (pattern discrimination). Phytoestrogens: Theoretical Concerns Versus Clinical Knowledge and Applications Britta Engert & Yiota Panayiotis In Vitro Studies Study Name Study Design Intervention Outcome Measure Conclusion Results DiPaola et al, 1998 10 1) Yeast assay 2) Menopause mouse model 3) Male patients with prostate cancer PC-SPES (chrysanthemum, isatis, licorice, Ganoderma lucidum, Panax pseudoginseng, Rabdosia rubescens, saw palmetto, scutellaria) 1) Yeast proliferation rate 2) Mouse uterus size 3) Human PSA and Testosterone level Marked oestrogenic effect in vitro and in vivo Santell et al, 2000 26 Mice inoculated with MDA-MB-231 cells (breast cancer cells) Genistein diet 1) Genistein concentration required to inhibit tumor growth in vitro 2) Genistein plasma concentration in relation to diet 3) Tumor growth with Genistein diet 1) Genistein concentration required to inhibit tumor growth can not be achieved with Soy diet 2) In vivo tumor growth not inhibited by Genistein Bodinet and Freudenstein, 2002 11 Cell Preparation Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa [CR]), on estrogen-dependent mammary cancers 1) CR-extract inhibited MCF7 cell (cancer cell) proliferation 2) CR-extract inhibited estrogen-induced proliferation of MCF-7 cells 3) Proliferation-inhibiting effect of tamoxifen was further enhanced by the CR-extract 1) Non-estrogenic, or estrogen-antagonistic effect of CR on human breast cancer cells 2) Breast cancer treatment with CR – extract is safe Wang et al, 2003 12 Osteoporotic mouse model Puerariae radix diet femoral bone mineral density Puerariae radix prevented osteoporosis Bodinet and Freudenstein, 2004 13 In vitro: MCF 7 and HeLa cell line Proliferation and toxicity assay using Black cohosh, Soy, Red clover Cell toxicity and proliferation 1) Black cohosh, Soy: no cytotoxic effect Red clover: cytotoxic at high concentration 2) Soy and Red clover enhance MCF 7 proliferation, Black cohosh doesn’t Xu et al, 2011 14 Menopause mouse model Tiáo-Gēng-Tāng(TG) Vs Estrogen Estradiol, LH, FSH levels, Estrogen Receptor (ER) expression TG less effective than estrogen in balancing female hormones, but stronger upregulation of ER In vitro: inflammatory breast cancer cells SUM-149 Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) 1) apoptosis rate 2) cell invasion assay 3) Gene expression profile 1) Increased apoptosis, 2) Reduced invasivenes, 3) Downregualation of cell cycle progression MartínezMontemayor et al, 2011 15 Cell culture studies suggest that some phytoestrogens may increase oestrogen sensitive cancers. This is in sharp contrast to early epidemiological studies which suggest a reduced breast cancer rate in Asian women, possibly phytoestrogen diet related.1 Most carcinogenic effects of phytoestrogens were only observed at nonphysiological serum levels, which can not be achieved through oral intake. Often results from pre-clinical studies (cell culture, animal) can not be translated into positive results in (human) clinical studies.16 Current research into Chinese medicinal herbs with phytoestrogenic components is driven by theoretical concerns around safety and potential commercial exploitation, such as, breast cancer risks and HRT replacements that promise treatment without the oestrogen side effects. However, it is difficult to justify such concerns given the evidence. Firstly, concerns around cancer and cell proliferation from the use of CHM with phytoestrogenic components have not been confirmed by clinical data and it appears that phytoestrogenic components are safe and efficient to treat mild menopausal symptoms. Overall, research is largely inconclusive. As Carreau et al27(p183) state from their own inconclusive findings: ‘This suggests that the estrogenic and/or anti-estrogenic activity of structurally diverse natural phytoestrogens is complex, which is consistent with published data that often give contradictory results for these compounds.’ Also, one can see from both the in vivo and in vitro studies, that the scientific methods applied do not account for CHM theory and the diagnosis of an individual patients syndromes. Typically research aims to find new biomedical components for exploitation in orthodox medicine, rather than aiming to show clinical efficacy of a CHM formula. Herbs are only considered in isolation and based on their active phytoestrogenic ingredients. In contrast, classical CHM uses herbs within polypharmacy formulas, leading to enhancement and buffer effects, and an overall more balanced treatment.28 Most current research forces CHM into a western medical framework, removing all the core CHM concepts, and consequently developing conclusions of limited value to CHM practice, both from an efficacy and safety point of view. The long track record of CHM has shown good empirical efficacy for menopausal symptoms with no obvious associated cancer risk. Clinical research applying current scientific methods (randomised control trials) is necessary to further consolidate this knowledge and secure the survival of CHM in the modern world. However, this research must take into account the classical CHM diagnostic framework and prescribing methods. CHM practitioners should lead the way and promote clinical settings that facilitate modern research and move away from a mostly historical approach. Ideally, CHM hospitals need to be established and, in collaboration with individual practitioners, become centres of clinical research. References and Bibliography 1. Peeters PHM, Keinan-Boker L, van der Schouw YT, Grobbee DE. Phytoestrogens and Breast Cancer Risk. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2003;77: 171-183. http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/med/20060803-200546/Peeters_03_Phytoestrogensandbreastcancerrisk.pdf (accessed 26 October 2012). 2. Hirata JD, Swiersz LM, Zell B, Small R, Ettinger B. Does Dong Quai Have Estrogenic Effects in Post-menopausal Women? A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial ..Fertility and Sterility 1997;68(6): 981-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9418683 (accessed 26 October 2012). 3. Quella SK, Loprinzi CL, Barton DL, Knost JA, Sloan JA, La Vasseur BL, Swan D, Krupp KR, Miller KD, Novotny PJ. Evaluation of Soy Phytoestrogens for the Treatment of Hot Flashes in Breast Cancer Survivors: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2000;18(5): 1068-74. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10694559 (accessed 26 October 2012). 4. Davis SR, Briganti EM, Chen RQ, Dalais FS, Bailey M, Burger HG. The Effects of Chinese Medicinal Herbs on Post-Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms of Australian Women. The Medical Journal of Australia 2001;174(2): 68-71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11245505 (accessed 26 October 2012). 5. Newton KM, Reed SD, LaCroix Z, Grothaus LC, Ehrlich K, Guiltinan J. Treatment of Vasomotor Symptoms of Menopause with Black Cohosh, Multibotanicals, Soy, Hormone Therapy or Placebo: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 2006;145(12): 869-79. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17179056 (accessed 26 October 2012). 6. Kwee SH, Tan HH, Marsman A, Wauters C. The Effect of Chinese Herbal Medicines (CHM) on Menopausal Symptoms Compared to Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) and Placebo. Maturitas 2007;58(1): 83-90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17689896 (accessed 26 October 2012). 7. Rotem C, Kaplan B. Phyto-Female Complex for the Relief of Hot Flushes, Night Sweats and Quality of Sleep: Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind Pilot Study. Gynaecological Endocrinology 2007;23(2): 11722. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17454163 (accessed 26 October 2012). 8. Lipovac M, Gruenhut C, Gocan A, Kurz C, Benedikt N, Imhof M. Effect of Red Clover Isoflavones Over Skin, Appendages and Mucosal Status in Post-Menopausal Women. Obstetrics and Gynecology International 2011;949302: 10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22135679 (accessed 26 October 2012). 9. Deng WM, Zhang P, Huang H, Shen YG, Yang QH, Cui WL, He YS, Wei S, Ye Z, Liu F, Qin L. Five Year Follow-Up Study of a Kidney Tonifying Herbal FuFang for Prevention of Post-Menopausal Osteoporosis and Fragility Fractures. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism 2012;30(5):517-24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22722637 (accessed 26 october 2012). 10. DiPaola RS, Zhang H, Lambert GH, Meeker R, Licitra E, Rafi MM, Zhu BT, Spaulding H, Goodin S, Toledano MB, Hait WN, Gallo MA. Clinical and Biologic Activity of an Estrogenic Herbal Combination (PCSPES) in Prostrate Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 1998;339(12): 785-91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9738085 (accessed 26 October 2012). 11. Bodinet C, Fraudenstein J. Influence of Cimicifuga Racemosa on the Proliferation of Estrogen Receptor-Positive Human Breast Cancer Cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2002;76(1): 1-10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12408370 (accessed 26 October 2012). 12. Wang X, Wu J, Chiba H, Umegaki K, Yamada K, Ishimi Y. Puerariae radix Prevents Bone Loss in Ovariectomized Mice. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism 2003;21(5): 268-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12928827 (accessed on 26 october 2012). 13. Bodinet C, Fraudenstein J. Influence of Marketed Herbal Menopause Preparations on MCF-7 Cell Proliferation. The Journal of the North American Menopause Society 2004;11(3): 281-289. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15167307 (accessed 26 October 2012). RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2011 www.PosterPresentations.com 14. Xu LW, Kluwe L, Zhang TT, Li SN, Mou YY, Ma J, Sun ZJ. Chinese Herb Mix Tiao-Geng-Tang Possesses Antiaging and Antioxidative effects and Upregulates Expression of Estrogen Receptors Alpha and Beta in Ovariectomized Rats. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2011;11: 137. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22206438 (accessed 26 October 2012). 15. Martinez-Montemayor M, Acevedo RR, Otero-Franqui E, Cubano LA, Dharmawadhane SF. Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth and Expression of Key Molecules in Inflammatory Breast Cancer. Nutrition and Cancer 2011;63(7): 1085-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21888505 (accessed 26 october 2012). 16. Rice S, Whitehead SA. Phytoestrogens Oestrogen Synthesis and Breast Cancer. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2008;108(3-5): 186-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17936616 (accessed 26 October 2012). 17. Aldercreutz H, Bannwart C, Wahala K, Makela T, Brunow G, Hase T, Arosemena PJ, Kellis JT, Vickery LE. Inhibition of Human Aromatase by Mammalian Lignans and Isoflavoid Phytoestrogens. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 1993;44(2): 147-53. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8382517 (accessed 26 October 2012). 18. Chen S, Kao YC, Laughton CA. Binding Characteristics of aromatase Inhibitors and Phytoestrogens to Human Aromatase. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 1997;61(3-6): 107-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9365179 (accessed on 26 October 2012). 19. Anastasius N, Boston S, Lacey M, Storing N, Whitehead S. Evidence That Low-Dose, Long-Term genistein Treatment Inhibits Oestradiol-Stimulated Growth in MCF-7 Cells by Down-Regulation of the PI3-kinase/Akt Signalling Pathway. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2009;116: 50-55. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19406242 (accessed 26 october 2012). 20. National Cancer Institute. Understanding Cancer Series. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/understandingcancer/estrogenreceptors/AllPages. Accessed 20 January 2013. 21. Bensky D, Clavey S, Stoger E. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica. Seattle: Eastland Press; 2004. 22. Boik J. Cancer and Natural Medicine. Oregon: Medical Press Publishing; 1995. 23. Duke JA. Handbook of Phytochemical Constituents of GRAS Herbs and Other Economical Plants. Florida: CRC Press Publishing; 1994. 24. Ziegler RG. Phytoestrogens and Breast Cancer. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004;79(2): 183-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14749221 (accessed 26 October 2012). 25. D’Anna R, Cannata ML, Marini H, Atteritano M, Cancerllieri F, Corrado F, Triolo O, Rizzo P, Russo S, Gaudio A, Frisina N, Bitto A, Polito F, Minutoli L, Altavilla D, Adamo EB, Squadrito F. Effects of the Phytoestrogen genistein on Hot Flushes, Endometrium and Vaginal Epithelium in Post-Menopausal Women: A Two Year Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Menopause 2009;16(2): 301-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19034051 (accessed 26 october 2012). 26. Santell RC, Kieu N, Helferich WG. Genistein Inhibits Growth of Estrogen-Independent Human Breast Cancer Cells in Culture but not in Athymic Mice. The Journal of Nutrition 2000;130(7): 1665-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10867033 (accessed 26 october 2012). 27. Carreau C, Flouriot G, Bennetau-Pelissero C, Potier M. Enterodiol and Enterolactone, Two Major Diet Derived Polyphenol Metabolites Have Different Impact on ER-Alpha Transcriptional Activation in Human Breast Cancer Cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2008;110: 176-185. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18457947 (accessed 26 October 2012). 28. Flaws B. Chinese Herbal Medicine and Estrogen-Dependent Tumors. http://bluepoppy.com/cfwebstore/index.cfm/feature/66/chinese-herbal-medicine--estrogen-dependent-tumors.cfm (accessed 27 October 2012).