Justice Systems - National Indian Justice Center

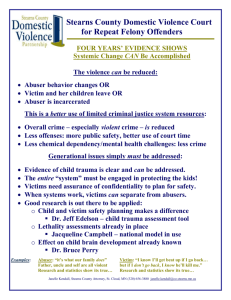

advertisement