FLL_WLdraft - Fisheries Conservation Foundation

advertisement

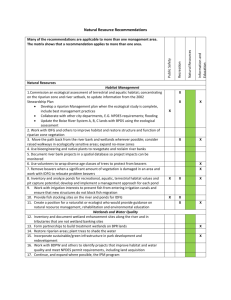

WATER LAW Robert Hirschfeld and Sarah Painter Table of Contents Part I: Introduction to Surface Water Law Part II: Riparian Rights A. Overview B. Coverage C. Principal Elements D. Administration E. Links with other Laws F. Citizen Involvement G. Effects on Aquatic Natural Resources H. Illustrative Judicial Rulings I. Limitations and Effectiveness J. Possibilities for Reform Part II: Prior Appropriation A. Overview B. Coverage C. Administration D. Principal Elements E. Links with other Laws F. Citizen Involvement G. Effects on Aquatic Natural Resources H. Illustrative Judicial Rulings I. Limitations and Effectiveness J. Possibilities for Reform References Introduction to Water Law: What is Water Law? Water law is traditionally classified as a branch of property law. It includes the legal rules explaining who can use water, in what ways, and for how long. In many settings, the use rights people possess are viewed as forms of private property, but they are unusual forms of property with features that reflect the public’s strong interest in how water is used. The defining characteristics of water make it a challenging resource to manage. Water is a fugitive resource with a myriad of uses, and it absolutely essential for life process. It is expected to fulfill many human needs, including drinking and household uses, raising farm animals, irrigation, mining, power, manufacturing, sewage, navigation, wildlife, recreation, aesthetic, and environmental values. Source: http://www.srh.noaa.gov/tae/cpm/woodruff_dam_pic.jpg Water Law Water regimes differ by region, and diverge in important ways from real and personal property law. Generally, water law is a study of property concepts as they relate to water, including: – – – – Water allocation Private and public access and use rights Transfer and termination of water rights Dispute resolution (between water users, uses, and intergovernmental entities) – Water institutions and governance Development of Water Law Developed from common law principles. (by courts) Water law in the United States developed from common law principles. This means that the law was developed by the courts, or some similar tribunal, in response to water conflicts or uncertainty, rather than through legislative or executive action. Some water law concepts, such as riparian rights, were inherited from Europe and modified by American water users and courts. Other water systems arose from the unique needs and experiences of Americans settling in the arid west. Trend toward codification Several states have now codified their water regimes into state statutes, regulations, and registration or permit requirements, and have appointed specific governmental entities to manage the water allocation system. This means that state legislatures or regulatory agencies have passed laws defining common law concepts such as the requirements for obtaining and limitations on using water rights. However, not all states have codified their water law, and even states with statutory grounding still may rely on common law standards for resolving water conflicts and policy. Source: original photo on file with author Two Major Water Law Systems Water law varies from state to states, and most states have separate systems for governing surface water and groundwater. There are two major U.S. systems for allocating surface water: Riparian rights, in which owners of land abutting water courses have certain rights to use the water, and Prior appropriation, in which water rights are established based on first-in-time diversion for a beneficial use. Generally, states in the Eastern United States where water is more abundant follow Riparian rights schemes, and arid Western states follow prior appropriation. However, several states have modified or hybrid versions of the two main systems. States with a Riparian Rights Systems for Surface Water: Alabama Arkansas Connecticut Delaware Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Iowa Kentucky Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Missouri New Hampshire New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina Tennessee Vermont Virginia West Virginia Wisconsin States with Prior Appropriation Systems for Surface Water Alaska Arizona Colorado Idaho Montana Nevada New Mexico Utah Wyoming Source: original photo on file with author States with Hybrid systems for Surface Water California Oklahoma Kansas Oregon Mississippi South Dakota Nebraska Texas North Dakota Washington Source: original photo on file with author When researching specific water law issues: This module contains only a summary of the major water law regimes, and how current water law systems affects fisheries and other aquatic natural resources conservation. When approaching a specific water law issue, it is important to research the particular state law which governs the situation. Most states have numerous statutory provisions which confer authority to use, develop, and regulate water resources on various entities. For example, in Illinois, which has not fully codified its water law into statute, there are still literally dozens of statutory provisions that confer authority on state and local entities, including the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, the Illinois Department of Agriculture, numerous principalities, public water districts, water commissions, public utilities, and sanitary districts, to use or otherwise affect water resources. Therefore, state-specific research is important. When is water law relevant to conservation interests 1) Resolving conflicts between competing users. Some water users, such as those with conservation, fish, and wildlife interests may want to maintain certain levels of instream flows. Other current or potential water users may want to divert water from the river or stream for personal or commercial use. Water law can determine which party should prevail when conflicts arise. 2) Resolving questions about ownership and use rights – Including claims of ownership by riparian owners, states, and the federal government – Questions about the rights of riparian owners and the rights of the public – Questions about a state’s ability to protect the rights of the public Effects of Water Law and Diversions on Aquatic Natural Resources Water law is largely about diverting water for human consumption, making it difficult to protect aquatic natural resources. Water Law and Diversions v. Fisheries Conservation: The Conflicts Several different groups compete for use and access to limited water supplies. - Agriculture - Cities, especially growing communities - Industry - Native American tribes - Recreation/aesthetics - Fish, wildlife, and other environmental concerns Each of these groups have different interests in how water should be allocated and used. Water laws must attempt to balance the competing interests, and more often than not, fisheries and aquatic resources are at the bottom of the list. Water Law and Diversions v. Fisheries Conservation: Problems for Fish As water is diverted and used, there are significant changes to the natural state of watercourses. – Withdrawals, dams, irrigation ditches, and land use patterns reduce instream flows, meaning there is less spawning habitat for fish. – Dams block access to habitat and spawning areas. – Lower water levels change the water temperature and flow speed which can affect fish health and survival rate. If water levels in a reservoir are particularly low, the water can be heated by the sun to the point where eggs and young fish are killed. – Some dams/diversions pump water from a river into smaller agricultural canals. Fish can be sucked into the pumps and killed. Fish ladders and fish screens which are intended to help fish navigate around dams and prevent fish from entering diversions may not be used or may offer inadequate protection – Sometimes fish swim into irrigation ditches during high flow times, and are unable to swim back out either because the ditch has dried up, or a fish screen is in place. – As water is returned to the waterway from agricultural uses, its temperature or chemical properties may be altered. Water Law and Diversions v. Fish fish ladder Drying irrigation ditch Fish screens on a dam Sources http://www.lakeoroville.water.ca.gov/about/stats/hatchery.cfm; www.historyforkids.org/.../maliirrigation.gif; www.fpi-co.com/images/applications-RiverDiver Two Major Water Law Systems With this background information about water law and diversions in mind, we will now consider the two major surface water law systems: Riparian rights and Prior Appropriation. Source: original on file with author. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Riparian Rights: Overview General Rule: Each landowner that borders on or is crossed by a water body may make reasonable use of the water on their riparian property within the particular watershed. Riparian rights are incidental to ownership of land bordering on water and pass with the transfer of property (even when not designated in a deed). Because the right attaches to the riparian land, riparian owners traditionally are not allowed to transfer the right to another place. For the same reason, riparian landowners do not lose their water rights through nonuse. Today, some state statutes now allow transfers of riparian rights to tracts off the watercourse, as long as the use is reasonable. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Coverage States with Riparian Rights Systems Alabama Minnesota Arkansas Missouri Connecticut New Hampshire Delaware New Jersey Florida New York Georgia North Carolina Illinois Ohio Indiana Pennsylvania Iowa Rhode Island Kentucky South Carolina Maine Tennessee Maryland Vermont Massachusetts Virginia Michigan West Virginia Wisconsin Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Principal Elements of a Riparian Rights System Who are riparian landowners? – Land must be contiguous (touching) the water source – The watercourse can be a stream or river in a definite and natural channel, lakes, ponds, and sometimes springs. Riparian rights normally do not arise out of artificial watercourses or diffuse surface water. (Diffuse surface water is water that has fallen to the earth, such as stormwater, but has not yet collected in channels). Source: original photo on file with author. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Nature of Riparian Rights Riparian landowners do not actually own the water body, nor do they own the water itself until they have lawfully diverted it. Instead, they “own” numerous rights to make use of the water. Modern riparian rights include: - right to waterway access - right to divert and use water (in times of shortage, water is shared by riparians, not allotted to a senior appropriator) - right to water purity (though this is now largely controlled by statute) - right to fish - right to protect the stream/river banks and riparian tract from erosion Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Doctrine of Reasonable Use Riparian doctrine: Each landowner bordering on a water body may make reasonable use of the water on their riparian property within the particular watershed. • Reasonable use is a limit on each riparian landowner’s right to the common supply. • Reasonableness is relative. It is most often determined by comparing one riparian’s water use with the interests and uses of other riparians. – This means that in determining the reasonableness of a particular water use, the use is not weighed against the possible environmental damage that the use may cause. Instead, it is compared to how other riparians are using water, and whether the particular use will impair the rights of other users. • Common law principles distinguish between natural and artificial uses. Diversions for natural uses, that is, domestic consumption, limited livestock watering, and subsistence gardening are nearly always reasonable, even if they diminish flows to the harm of downstream riparians. This is based on the assumption that natural uses seldom significantly diminish flows and are necessary for basic survival; hence they are inherently reasonable. All other uses are artificial uses. They include large-scale irrigation, manufacturing, hydropower generation, and mining. They are permissible only to the extent they are reasonable under the circumstances. Determining reasonableness requires scrutiny of their potential impact on downstream users. • State statutes may create a hierarchy of uses that affect a reasonable use inquiry, or a statute may flatly declare a use reasonable. For example, Iowa ranks “human drinking water” as the highest priority in times of water shortage, with “agricultural uses” second most important. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reasonable Use Continued When conflicts arise between two riparians and a court or administrative body determines whether a particular riparian’s use is reasonable, common factors that are considered include: - purpose of the use - suitability of use to the watercourse - compatibility of use to other uses on the watercourse - economic value of the use - social value of the use - extent and amount of harm to other riparians - practicality of avoiding harm *Note that under the reasonable use rule, a riparian owner whose use is not adversely affected by a reduction in streamflow or water quality has no basis for a legal action. This means that unless there is a riparian owner who specifically uses the water for fishing or for something else that requires a minimum instream flow or water quality level, no one can bring a lawsuit relying on water rights to protect fish. Even if there was a riparian owner to bring such a lawsuit, the court would evaluate the challenged use based on the above factors and could possibly conclude that protecting fish is not economically beneficial or compatible with existing uses. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Reasonable Use Continued: Diversion and Place of Use Limits Traditionally, there were two major limitations on riparian owners: natural flow theory and place of use restrictions. a) Natural Flow Doctrine: Early riparian rights were restricted to uses that would not diminish the natural flow of the waterway. This basically limited water withdrawals to use for domestic purposes such as drinking water. Although this rule provided better protection for fish and other aquatic natural resources because it maintained instream flows, the natural flow limitation interfered with community growth and industrialization. It was gradually replaced by the reasonable use doctrine. See, e.g., Stratton v. Mt. Hermon Boys’ School, 216 Mass. 83 (Mass. 1913). b) Place of Use restrictions: Several states which follow riparian rights water law impose place of use restrictions which prohibit riparian owners from using water off of the riparian tract or outside of the watershed. One theory behind these restrictions is that if the water is used within the watershed, it may eventually return to the waterway. Today, most states allow riparians to use water off the riparian land, or to transfer the water rights to a non-riparian user, subject to the reasonable use requirement. In other words, as long as the water use does not impair the reasonable use of other riparians, the use is valid. See, e.g., Pyle v. Gilbert, 245 Ga. 403 (Ga. 1980). Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Administration of Riparian Rights System Because water law systems vary between states, each state has different entities which may affect water law administration. Within riparian states, several tools are used to administer water law including common law principles, registration and permitting schemes, and enforcement systems. States rely on these tools to varying degrees. Some states, including Louisiana, New Hampshire, Vermont, Rhode Island, and West Virginia, continue to reply primarily on common law principles and have not enacted significant registration or permitting requirements. Other states, including Iowa, Maryland, Florida, Minnesota, Mississippi, Virginia, Kentucky, Connecticut and Delaware, have significant regulatory permitting requirements with relatively low thresholds. In such states, administrative agencies play a much greater role in administration of water law. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform a) Common law principles: • utilized in conflict resolution and policy making. Include: – Reasonable use doctrine; Natural v. artificial uses – Diversion and place of use limitations – Determinations of whether a specific waterbody gives rise to riparian rights (resolution of debates over ownership and boundaries)/ b) Registration: • used to monitor water use. • May be used statewide for all water withdrawals, or may be limited to certain types. (ex: in Illinois and Ohio, only groundwater withdrawals are registered). c) Permitting: used to control water use by attaching conditions and ensuring that proposed uses do not interfere with existing users • May supplant a state’s registration system (because water withdrawals are monitored through the permit process), or may apply to only certain parts of the state. (ex: in Illinois, permits are required for significant new withdrawals from Lake Michigan, but in other parts of the state, registration is all that is required, and only for groundwater withdrawals that exceed 100,000 GDP). • May apply to groundwater, surface waters, or both. • May apply to withdrawals (actual use) or facilities (capacity for use). • May be of limited duration. • May be tied to location or use. • Permitting requirements may only be triggered at certain volumetric thresholds. • May be linked to other regulatory processes (such as land-use and site development regulations). • Some permits have requirements to protect instream flows. • May prioritize uses. • May target specific areas for extra protection and withdrawal limitations. d) Enforcement: Enforcement schemes may or may not be effective. Even where permitting or registration systems do exist, enforcement may be largely voluntary because states do not have resources or political support to implement permitting or enforce permits to the extent implied by the law. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Major Players in Water Law Administration: The extent of any of the following entities’ involvement in water law administration will depend on the system established in a particular state. However, in most systems, each of the following individuals or entities plays some role in administration. a) State agencies: often responsible for registration or permitting programs, may have enforcement responsibilities. Agencies administer permits pursuant to legislative guidance, but may have authority to set standards and procedures for registration, permitting, and conflict resolutions. Ex: State Department of Natural Resources, State Water Control Boards, State Watermasters, Water management districts b) Riparian landowners: involved in administration because a state may rely on voluntary compliance/enforcement; conflicts may have to be resolved between individual users in a court or other administrative tribunal c) Courts: apply common law standards, formulate policies d) State Legislatures: codify water law systems, especially important as states move away from common law doctrines Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Relationship of Riparian Rights to other Laws: Regulatory Overlap and Federal Limitations Several state and federal statutes affect water rights. 1) The Clean Water Act (CWA) and the Safe Drinking Water Act, for example, provide for increasing water quality and treatment standards for surface and groundwater sources and wastewater discharges. - Riparian owners are obligated to comply with CWA standards when utilizing their riparian rights. When a riparian owner challenges another riparian’s water use as unreasonable, it may be easier to prove unreasonableness if the CWA is being violated. 2) Remediation efforts affecting water supplies are reflected in the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Recovery Act (CERCLA) and Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). 3) Species and habitat protections are contained in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the Endangered Species Act and others. - Riparians must comply with ESA and NEPA if a water use triggers the requirements of these statutes. These federal statutes highlight and exacerbate the deficiencies of common law riparianism. Environmental concerns are not a key element of the riparian water law doctrine. Water law developed simply for the purpose of allocating water for human use. Many federal environmental statutes increase the costs of securing and using water resources, increase conflicts between competing reasonable uses, and otherwise affect available supplies. Frequently, the agencies responsible for implementing these federal statutes do not coordinate with the agencies who manage state water rights. Until riparian rights systems incorporate similar environmental goals, conflicts will continue to arise. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Citizen Involvement and Remedies In riparian jurisdictions, riparian rights can only be asserted by riparian landowners. Even in states that require riparian owners to maintain instream flows, it is not clear that groups most interested in instream flows, such as environmental groups and recreationists, would have standing to sue in state courts to protect their interests. (“Standing” is the requirement that parties demonstrate to the court that they have a sufficient connection to and harm from the challenged law or action that justifies their participation in the case. To establish standing, parties must usually show 1) that they have or will imminently suffer injury from the challenged law or action, 2) that there is a causal connection between the injury and the conduct complained of, and 3) that a favorable court decision will redress the injury.) In addition, the risk and cost of water rights litigation deter many potential plaintiffs even where standing would not be a barrier. However, there are some situations in which members of the public can be involved in water law and diversion issues. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Opportunities for Public Participation a) Direct intervention in lawsuits: Appropriate state agencies or conservation groups in some cases attempt to become a party in certain riparian water disputes on the basis of ownership of riparian land (such as a state park or recreational area) adversely affected by low flows or pollution. Groups such as Nature Conservancy have utilized direct intervention as land owners. Conservation groups can also request to intervene at the court’s discretion under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24 or the state equivalent. If the court grants a group’s intervention request, the group becomes a fullfledged party to the litigation, subject to limitations placed by the court. - Drawbacks and limitations on direct intervention: risk, cost, standing b) Amicus Briefs: where direct intervention as a party is not possible, citizens may be able to file amicus curiae briefs to bring fisheries and other public interest considerations before a court deciding a case involving a conflict between water users. The decision whether to admit information submitted amicus curiae lies with the discretion of the court. Drawbacks: not actually a party to the lawsuit, varying degrees of influence and effectiveness c) Nuisance law: Sometimes, public citizens suffer a special injury and can satisfy the standing requirements to bring a public nuisance suit against a riparian owner who is causing harm to aquatic natural resources. For example, a commercial fisherman who relies on a particular waterway to maintain his living would have standing to sue under public nuisance. See, e.g., Burgess v. M/V Tamano, 370 F. Supp. 247, 250-51 (D. Me. 1973); Columbia Rivers Fishermen’s Protection Union v. City of St. Helens, 87 P.2d 195, 197 (1939). d) Public Use: the public has a right of navigation and fishing in all navigable waters. See, e.g., Public use rights may be asserted under the Public Trust doctrine. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Public Trust Doctrine When states entered the Union and took ownership of land beneath their navigable waterways, they took title subject to public use rights of fishing and navigation. As lands were transferred to riparian owners, the riparian owners also took title subject to public use rights. It has been argued that the public is entitled to sufficient streamflow to preserve the public right to navigate and fish in all navigable waters, and that that state has a duty to protect and manage water courses for these public purposes. It is unclear whether the public trust doctrine protects only rights to commercial navigation and fishing, or whether it also encompasses recreational, aesthetic, and environmental values. It is also unclear whether the public trust doctrine imposes an affirmative duty on states to protect public use rights. Source: original photo on file with author Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Effect of Riparian Law on Aquatic Natural Resources The Problems: Protecting fisheries and other aquatic natural resources is not a key component of riparian doctrine. Riparian rights exist to allow for diversion of water for human use and consumption. As water is diverted and used, there are significant changes to the natural state of watercourses. The most serious consequence of diversions to fish is the decrease in instream flows, which changes the water temperature, flow speed, and chemical properties of the water. Dams and other diversions also alter wildlife habitat and fish spawning areas. Irrigation ditches can be especially harmful because fish swim sometimes swim into irrigation ditches during high flow times, and are unable to swim back out. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Applying Riparian Law to Fish Conservation Working within existing riparian principles, there are limited methods for addressing environmental concerns. 1) Institutional mechanisms addressing environmental concerns In riparian jurisdictions, environmental concerns are largely addressed in two main forms: a) measures incorporated into state water law that integrate instream water uses into the process for allocating water among competing uses (only in states with standardized registration or permitting systems) -- Ex: restricting permits in areas ecologically sensitive areas, requiring threshold instream flows, placing fisheries and wildlife protection near the top of a hierarchy of reasonable uses b) direct regulatory measures that supplement riparian principles by restricting water development activities. -- Ex: Federal and state environmental statutes such as the Clean Water Act or Endangered Species Act which place affirmative duties on riparian users 2) Ability of riparian landowners to address environmental concerns a) Water must be shared among all riparian users. The riparian doctrine requires that the available water supply be shared among riparian owners along the course of a stream. This requirement provides some protection for instream values and aquatic natural because it ensures that no user can totally deplete the flow of a stream. b) Limitations on transfers out of watershed. The riparian doctrine’s restriction to interbasin transfers also provides protection to instream uses by limiting withdrawals. However, the fact that the doctrine is not likely to prohibit transfers where water is available in excess of the needs of the riparian landowners diminishes the significance of this protection. c) Riparian rights to fish and access clean water. Riparian landowners can sue if another riparian’s use is causing pollution or obstruction of flow that is interfering with their own riparian rights, including the right to fish. However, such complaints are analyzed by applying the vague reasonable use doctrine. Furthermore, if there are no riparian landowners with interests in instream activities, significant harm may occur to instream values without attention from the courts. Even where lawsuits are initiated, attention may be focused on competing offstream water needs with little attention given to instream uses. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Illustrative Judicial Rulings Springer v. Joseph Schlitz Brewing Co., 510 F.2d 468 (C.A.N.C. 1975). Riparian landowners sued an upstream brewery for pollution that “caused six unprecedented fish kills and otherwise impaired the quality” of the waterway. In this case, the court recognized that riparian owners have the right to “scenic use and enjoyment” of the river. In states that recognize a similar riparian right, riparians who are not actually fishers, but instead watch and enjoy wildlife, can have protections against pollution and diversions which interfere with wildlife in the waterways. As the North Carolina court explained: “[A] riparian landowner has a right to the agricultural, recreational, and scenic use and enjoyment of the stream bordering his land, subject, however, to the rights of upstream riparian owners to make reasonable use of the water without excessively diminishing its quality. Though he does not own the fish in the stream, the riparian owner's rights include the opportunity to catch them. Interference with riparian rights is an actionable tort, and a riparian owner may join several polluters as joint tort-feasors. Michigan Citizen’s for Water Conservation v. Nestle Waters North America, 479 Mich. 280 (Mich. 2007). A Water Conservation Organization and its member property owners brought an action against a spring water bottling company for an injunction against pumping groundwater. The plaintiffs alleged that by pumping groundwater, the bottling company was interfering with riparian rights of fishing, recreation, and wildlife viewing. The court of appeals entered the injunction, but the Michigan Supreme Court reversed, holding that the organization and members lacked standing. State v. Haskell, 84 Vt. 429 (Vt. 1911). This case explains that a riparian landowner “cannot lawfully kill, materially injury, or obstruct the free passage” those fish which he does not lawfully catch. Further, riparians do not have the right to unreasonably pollute or degrade the waterway because every riparian shares a common right to use and enjoy the water. Use and enjoyment includes the “right to have fish inhabit and spawn in the stream, for which purpose they must have a common passageway to and from their spawning and feeding grounds.” Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations/ Effectiveness Reform Effectiveness and Limitations of Riparian Rights The riparian system is fairly effective is fulfilling its purpose of allocating access and use rights in waters. However, the needs and priorities of the nation have changed in the many years which have passed since the riparian rights system was first established in early America. Today, there is a keen interest in protecting aquatic natural resources, but the riparian rights system has failed to incorporate conservation and ecosystem values. Major Deficiencies in the Riparian Rights System: 1) Failure to protect instream flows. Cumulative affects of several "reasonable uses" on one watercourse can result in reduced stream flows, deterioration of water quality, and the inability to protect ecosystems and wildlife habitats or recreation uses. 2) Vagueness of the reasonable use standard. The reasonable use standards provide little certainty regarding the nature and extent of water rights. It is often difficult to define with a fair degree of certainty the existing water supplies and uses, because whether a water use is reasonable is always relative to the other existing uses on a waterway. This uncertainty makes it difficult to manage water resources in times of scarcity, or to manage water for purposes such as conservation. The uncertainty also means that existing and proposed reasonable uses are not fully protected, which impedes planning, investment, and economic development that requires assured water supplies. Finally, the reasonable use standard makes it difficult to bring legal action for protection of stream flows, because a riparian can only bring an action if his own use is being impaired by another riparian’s use of the watercourse. 3) Reliance on common law litigation to resolve conflicts. (especially where only riparian owners have standing) Under the riparian doctrine, consideration of instream water quality and quantity issues may depend on the fortuitous location of a particular riparian landowner interested in maintaining instream uses. If there are conflicts between riparian landowners, or if a public right is asserted, such disputes often are resolved by courts which can reach inconsistent or contradictory results. Evidentiary presentations are controlled primarily by the litigants and fact specific situations, and there may be little or no consideration of broader public policy or conservation issues. 4) Failure to recognize the hydrologic interrelationship between groundwater and surface water. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Possibilities for Reform “Water, taken in moderation, cannot hurt anybody.” Mark Twain (1835-1910) Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photograph’s Division Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Possibilities for Reform of Riparian Rights 1) Comprehensive, natural resource based long-term planning on a larger scale. State legislatures and agencies need to move away from the idea that consumption is the highest priority for water resources to the concept that maintaining natural balance is important for securing longterm interests of the state and effectively using water resources. 2) Increased focus on protecting instream flows State agencies need mechanisms to stop diversions when necessary for conservation. Some states now include protection of instream flows as part of their regulatory system. For example, Minnesota requires cessation of downstream withdrawals if instream flows are impaired, threatening fish, wildlife, or drinking supplies. Other states have not incorporated minimum flows into water management, or have only granted limited authority to research or study the impacts of instream flows on human consumption and future human needs. 3) Greater opportunities for public participation. Standing should be expanded for parties with an interest in instream flow protection. 4) Coordinate regulation of water quality and quantity In many states, including Illinois, the authorities regulating water quality are different than those managing water quantity. Both aspects of water management are important for protecting aquatic ecosystems. 5) Trend toward statutory codification and permitting systems In response to perceived deficiencies, several riparian states have moved to, or considering moving to comprehensive permitting systems. However, comprehensive permitting also has limitations including overregulation, expense, inefficiency, and entrenchment of environmentally harmful uses. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Prior Appropriation Overview • Prior appropriation is the body of water law that governs the allocation of water resources in the western United States. The doctrine of prior appropriation was developed during the westward expansion of the 19th century to meet the needs of water users. • Water in the western United States is scarcer and less dependable than in the east, so the riparian rights system was not as practical. • Early application of prior appropriation was first by miners on public lands and later by farmers who claimed exclusive rights to water taken as necessary for their mining and farming operations. • In light of long-standing policies that economic development requires full utilization of a natural resource, rights to water have historically been given to those who took the water from its source and applied it to a beneficial use. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Prior Appropriation Overview Prior Appropriation was designed to encourage diversion of water from its source for application to agriculture in the arid west. By requiring that the water be put to use, hording was to be discouraged. Due to its scarcity in the west, water has been and remains a highly valuable resource. Exclusive control over such a precious resource, without a use requirement, would give an inordinate amount of power to those that horded it. Thus, lawmakers tied a water user’s right to a specified amount of water directly to the actual use of the water. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Prior Appropriation “ I tell you gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” John Wesley Powell 1834-1902 Limitations Effectiveness Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Prior Appropriation • The basic functioning of the prior appropriation system is very simple – first in time, first in right. • Water is generally considered to be a public resource unowned by any individual or entity. The owner of the property right has a right in the use of water once it has been diverted and applied to a beneficial use. Water, as a resource, is separated from land ownership, unlike under the riparian rights system. • The date of the appropriation determines a water user’s priority within the system. Prior appropriation recognizes superior rights in anyone who put water to use anywhere over anyone who later began using water. If water is insufficient to meet all needs, early appropriators are allotted their water first, with later appropriators receiving only some or even none of the water to which they have rights. • Once a party puts water to a beneficial use and complies with any statutory requirements, the water right is perfected and remains valid so long as it continues to be used. • This water right is transferable, with certain limitations. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Prior Appropriation Coverage • Prior appropriation, as a state property law, applies only in those states following the system. • States following prior appropriation: – AK, AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, WY • Some states use a hybrid riparian/prior appropriation system. Those states include: – CA, KS, MS, NE, ND, OK, OR, SD, TX, WA • Equitable Apportionment Doctrine – The Supreme Court of the United States has developed the “Equitable Apportionment Doctrine” to deal with interstate allocation disputes, the purpose of which is to ensure that water is apportioned equitably among the states. – The Supreme court has, on occasion, deviated from adherence to strict priority in allocations when necessary to achieve equity between states. Source: http://academic.emporia.edu/aberjame/wetland/canal/canals.htm Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Administration of Prior Appropriation • Permitting – Nearly all states now require a permit for new appropriations. – These permits are generally codifications of the traditional requirements for a water appropriation, providing a means for the state to keep track of its water resources. Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/agroblogger/2387606164/ Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Administration Continued Transfers – A water right can be transferred, under certain conditions, to another user or another use. – In order to transfer the use right, there must be a showing that the transfer will not harm the vested use rights of any junior users. • Junior appropriators have a vested right to have the conditions of the river remain as they were when their appropriations were made. Such rights make it very difficult for senior users to change the nature of their use. – This “no harm” rule is strictly interpreted. • Such a strict reading is part of a general policy for protecting junior users from interference with their water rights. • This strict interpretation practically results in the limited transferability of water rights, especially those transfers that seek to put the water to a new use. – The mere prospect of legal challenges by potentially-affected users can impair the transferability of water rights. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Administration Continued • Transfers & Changes in Nature/Place of Water Use – Simple transfers between users of a water right, without change to the nature or place of the water use are common and not problematic because they pose no threat to junior users – It is much more difficult to change the nature or place of use, whether by the original or a new user. Such changes are likely to affect the water rights of junior users Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Administration Continued • Difficulty in shutting down wasteful water uses – When water rights are first perfected, the appropriator has broad freedom to tailor that right, with very few restrictions. Most uses are considered beneficial, and few deemed wasteful. – But once use begins, the water right becomes narrowly tailored to the particular specifications set at the time of appropriation. A narrowly tailored water right is difficult to change or transfer without affecting another user in this highly interlocked system. – Because it is difficult to transfer water rights, many current wasteful water uses continue. Even if the net effect of a transfer would be positive in terms of overall efficiency of water use, the transfer is not allowed if it harms a single junior user. – Prior appropriation is structured to protect past uses, often regardless of their inefficiency and detrimental effects on landscapes and fish and wildlife. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Preferences – Many states have statutes that express preferences for certain water uses. These are public policy concerns, which can include conservation. – Preference laws primarily apply to new applicants, giving preference to particular uses among those permit applications simultaneously filed. – In times of shortage, preferred uses could potentially take priority over non-preferred senior uses. • In practice, however, preference statutes are not interpreted to allow such an application of the law as would disrupt the vested priority of uses. • Disruption of the priority system would undermine the foundational purposes and functioning of the law of prior appropriation. • Disruption of the priority system could also amount to a “taking” of the property right in the water, requiring compensation to be paid to those senior users whose water was given to junior users.. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Elements of a Valid Appropriation To appropriate, water must be diverted with an intent to appropriate it for a beneficial use • Traditional Elements/Requirements – Intent to apply water to a beneficial use – Actual diversion of water from a natural source – Application of water to a beneficial use within a reasonable time • Many states now require a permit from an administrative agency in order to newly appropriate an amount of water. – These state procedures assure compliance with the common law rules (traditional elements/requirements) for establishing the water use right. – Public interest concerns such as conservation may be weighed during the permitting process. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Diversion To appropriate, water must be diverted with intent to apply it to a beneficial use • Diversion, generally, is an alteration of part or all of a stream’s flow away from its natural course. – Historically, diversion has meant an actual physical diversion of the water such as damming or channeling. Such a requirement is problematic for claiming a water right for the purpose of maintaining the instream flows necessary for fish and wildlife habitat. – Some states have begun to recognize the need to maintain minimum instream flows, and have carved exceptions to the physical diversion requirement – see the next slide. • Due Diligence – A would-be appropriator must finish construction, divert, and apply water within a certain amount of time, depending on state law, and individual circumstances. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Diversion To appropriate, water must be diverted with intent to apply it to a beneficial use • Some states no longer require actual, physical diversion from the stream in order to establish a new water use right. – Some states have recognized the need to maintain minimum instream flows for various reasons including energy, aesthetics, recreation, and conservation of fish and wildlife habitat. – States may thus recognize an instream right to water, which requires that a specific amount of water be allowed to flow through the stream at particular places. – In many such states, instream flows can only be appropriated by the state or a state agency, though the state may act at the request of a private party or other entity. – Relaxing the requirements for what constitutes “diversion” for the purpose of appropriating a water right is one of the major areas where reform of the prior appropriation system is possible and necessary if fish habitat is to be protected. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Beneficial Use To appropriate, water must be diverted with intent to apply it to a beneficial use. • • • • • Traditionally, “beneficial use” meant offstream consumptive use. Historically, instream uses were deemed inherently wasteful as the purpose of the prior appropriation system was to foster economic development through actual agricultural, industrial, or municipal use. Since there is no duty to abate use or share with other appropriators during a time of drought, this consumptive, offstream interpretation of “beneficial use” has often resulted in streams being pumped dry or very low, severely degrading fish habitat. Water may be appropriated for any use that the state deems beneficial. More economically or socially useful purposes are generally not preferred over less useful purposes in regards to meeting the “beneficial” requirement and maintaining the water right. Beneficial Use is now specifically defined in most state statutes. All prior appropriation states consider domestic, municipal, agricultural, and industrial uses to be beneficial uses. Some states have more recently accepted recreation, aesthetics, and conservation as beneficial uses. State statutes can setup a hierarchy of preferred uses, as discussed in the Administration section above. These preferences are used administratively to determine the allocation of new permits for water rights. Preferences are sometimes used to allow holders of rights for preferred uses to condemn less preferred uses for compensation. – e.g. During a time of drought, a municipality may be able to condemn an agricultural water use right in order to provide water to the populace. Compensation would have to be given to the farmer whose use was condemned. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Beneficial Use Continued • The right to use water does not include the right to waste it. In practice, this provision often lacks real force as few uses are actually considered wasteful. Much of the irrigation in the western United States is grossly inefficient in terms of economy and ecology, and yet it is the single largest water use and remains the gold standard for the concept of “beneficial use.” • Is “beneficial use” an evolving concept? – In determining what “beneficial use” is, lawmakers may look to what was beneficial at the time the water was first appropriated, or they may judge the usage under more contemporary constructions or interpretations of this concept. – In order for the “no waste” provision to have any teeth, beneficial use must be considered an evolving concept. This could put an end to water practices that have become wasteful, either trough changed natural conditions, or through increased knowledge of the hydrological system. – An evolving concept of beneficial use could also allow for instream, non-consumptive appropriations and uses of water under the law. Since the single greatest threat to fish populations in western states is lowered water level due to diversions, there must be some way to end wasteful diversions and keep water in the watercourses if the fish are to survive. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Beneficial Use Continued • Once water is put to a beneficial use, the water right is perfected – Senior use rights can defeat more socially important, efficient, or economically valuable junior use rights. This often results in the problem of climatically unsuitable senior agricultural uses in arid regions taking precedence over junior municipal or domestic use. – Statutes can setup a hierarchy of preferred uses. These preferences are generally administratively to determine priority of simultaneously filed applications for water permits. These preferences could also be used to allow preferred junior users, such as municipalities, to condemn less beneficial senior uses. – As detailed above, under modern interpretations of beneficial use, the right to use water does not include the right to waste by excessive applications. However, irrigation of climatically inappropriate crops does not generally fall within this definition of waste • The property where water is applied need not be adjacent to the water source, and usually does not even need to be within the source’s watershed. The purpose and functioning of prior appropriation law was to take water from scattered and limited sources and apply it to beneficial uses wherever they may be. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reasonable time, Using Reasonable Diligence • The extent of the appropriative right is a quantity of water that can be put to beneficial use within a reasonable time, using reasonable diligence. • While reasonable is a vague and pliable term, the result is that the incentives are placed to divert water quickly in order to perfect the right, and not to allow water to remain in the stream. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Loss of Right: “Use it or lose it” • Long term failure to use the appropriated right can result in the loss of that right. – i.e. failing to use the amount of appropriated water for the purpose for which it was appropriated. • Intentional disuse may be construed as abandonment with the amount of water abandoned reentering the river system and available for new appropriation. • Unintentional disuse results in forfeiture in some states. • The incentives are for full and sustained consumptive use of water, depriving river systems of instream flows and damaging fish habitat. Even in times of heavy rainfall where the full amount of water appropriated is not necessary to meet the needs that it was originally appropriated for, the right holder may need to continue to withdraw their full amount in order not to lose it. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Interaction with Other Laws Wild and Scenic Rivers Act – The purpose of the Act is to preserve in a free-flowing condition certain rivers possessing outstanding “scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, and other similar values…” – The effect is to protect instream flows by prohibiting projects that would affect flow. – The Act is prospective, blocking future projects, and does not have force over prior appropriators. • Removing water from the appropriation system to maintain instream flows would be a taking of the senior appropriator’s private property right. Such rights must be purchased and would be quite expensive. Source: original photo on file with author Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Federal Reserve Water Rights Doctrine • • • When the United States sets aside lands for special use such as a park, military base, national forest, or Indian Reservation, it also reserves an amount of water sufficient to fulfill the purposes of that reservation. Priority is determined as of the date of the reservation, with the right vesting in the government, whether or not the water has ever been used since that date. Since the government can claim a superior right to water that it may not have historically used, but currently needs, this doctrine can cause rights dislocation among those who appropriated after the date of the reservation. – Thus, courts have narrowly construed the extent and scope of federal reserved rights. In United States v. New Mexico, the US Supreme Court rejected the claim that Congress intended to reserve minimum instream flows for aesthetic, recreational, and wildlifepreservation purposes (for the particular National Forest in question) despite strong evidence to the contrary. – Federally reserved rights are also quantified in state courts, and the states may have a strong interest in minimizing the amount of water reserved to the federal government. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Citizen Involvement • Citizens are primarily involved with western water law as appropriators or would-be appropriators. Citizens can, of course, always become politically involved at the level of the state legislature, putting pressure on lawmakers and seeking change to prior appropriation laws. Certain changes necessary for protecting fish habitat, such as redefining beneficial use to include instream use and to exclude wasteful agricultural practices, are incumbent upon the political will of the people of a state. In states where instream appropriations are allowed, citizens can get together to appropriate (or lease from an appropriator) an amount of water for instream use, or put pressure on the state government to do so. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Effects on Aquatic Resources • The law of prior encouraged almost two centuries of diversions from watercourses. • These diversions have dramatically altered the habitat of the fish and wildlife living in and around these watercourses, principally by lowering the amount of water. Landscape-scale problems with water use in the West • Too much water is wasted for ill-conceived purposes and through inefficient methods of delivery. • Too much water is used for irrigation of crops not suited for western growth. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform In re Adjudication of the Existing Rights to the Use of All the Water – This case before the Montana Supreme Court details the common law elements of prior appropriation water law as well as evidencing how this law can be changed to maintain instream flows for the benefit of fish and wildlife. – This opinion overrules a previous case, holding that “beneficial use” for the purpose of a valid water appropriation claim can include uses for fish, wildlife, and recreation, and that non-diversionary uses for these purposes are valid under the law.. Source: original photos on file with author. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations/ Effectiveness Effectiveness and Limitations of Prior Appropriation • The prior appropriation system is very effective at what it purports to do, moving water out of streams and applying it to consumptive use. It is not effective at keeping instream the water necessary for maintaining the health and integrity of watercourse ecosystems. In order to do so, reform will be necessary. • The emphasis on protecting the vested rights of junior users results in great difficulty in transferring use rights to more valuable or efficient uses. • “Beneficial use” and “waste” are largely meaningless concepts, especially in the context of irrigation for agriculture. However, simply by their existence in the law, the framework is in place for more strictly regulating the efficiency and true beneficence of water uses. Redefinition and reinterpretation is necessary. • So long as the primary purpose of western water law is to protect prior users at all costs and regardless of the nature of use, thee law will remain part of the problem to fisheries. Reform Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Possibilities for Reform of Prior Appropriation • Give real meaning to the “beneficial use” requirement – This would serve to eliminate many currently allowed, but highly wasteful water practices in the west. The vast majority of water in the west is used to irrigate crops. Many of these crops are not suited for growth in that particular climate. If there was also an expended conception of the meaning of waste under the law, so that it included inefficient irrigation practices, enough water could be freed up to provide for population centers as well as to remain in watercourses. – Maintenance of instream flows could also be construed as a beneficial use, and not as waste. There is a wealth of reasons why maintaining minimum flows is beneficial, conservation of fisheries not least among them. The law needs to recognize this. • Allow for private condemnation for preferred uses. – If the state creates a hierarchy for preferred uses based on the public interest, water rights could be more easily transferred and moved to better and more efficient uses when parties are willing to pay for those rights. Overview Coverage Administration Principal Elements Links with other Laws Citizen Involvement Effects on Aquatic Resources Illustrative Rulings Limitations Effectiveness Reform Protecting Minimum Flows under Prior Appropriation • Some states and state agencies have set up regulations requiring minimum instream flows. There are two possible methods for this. – 1. Removing a certain amount water from the appropriation system • Under the current law, this would upset the strict priority system, and would bring takings challenges by water users whose rights were interrupted or taken away. If the state decided to pay rights holders for removing this amount of water from the appropriation system, the cost would be enormous. – 2. Newly appropriating water for instream flows • This can only be done if diversion is not actually required, and beneficial use is defined within the state so as to allow instream use. Even where permitted, it is often only the state or a state agency that can appropriate water for instream use. To give greater protection for instream flows, private parties could be allowed to appropriate instream use rights. • New appropriations would still be junior to all previously-existing water rights, and would thus not address the problems of long-standing wasteful uses. • Ultimately, wasteful water practices must be ended, and the law must encourage reallocation of water rights to higher and better purposes. References Cases: Burgess v. M/V Tamano, 370 F. Supp. 247, 250-51 (D. Me. 1973). Columbia Rivers Fishermen’s Protection Union v. City of St. Helens, 87 P.2d 195, 197 (1939). National Sea Clammers Assn. v. City of New York, 616 F.2d 1222, 1234-35 (3d Cir. 1980). State of La. ex rel. Guste v. M/V Testbank, 752 F.2d 1019, 1030 (5th Cir. 1985). Munninghoff v. Wisconsin Conservation Comm’n, 255 Wisc. 252 (1949). Other Sources: - Anderson, Terry L. & Pamela S. Snyder. Priming the Invisible Pump, Property & Envtl. Research Center Policy Series, Feb. 1997. - Beck, Robert et al., Assessment of Illinois Water Quantity Law: Final Report, July 1996, available at http://www.isws.illinois.edu/iswsdocs/wsp/IlWaterQuantityLaw.pdf. - Caponera, Dante A. Principles of Water Law and Administration. 1992. - Foran, Paul G. et al, Survey of Eastern Water Law: A Report to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Sept. 1995, available at http://www.isws.illinois.edu/wsp/law.asp. - Freyfogle, Eric T. Natural Resources Law: Private Rights & Collective Governance. 2007. - Freyfogle, Eric T. and Dale D. Goble. Wildlife Law: Cases and Materials. 2002. - George A. Gould, et al. Cases and Materials on Water Law. 2005. - Getches, David. Water Law: In a Nutshell. 2d ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co., 1990. - Gillian, David M. and Thomas C. Brown. Instream Flow Protection: Seeking a Balance in Western Water Use. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1997. -Pharris, James K. and Tom McDonald. An Introduction to Washington Water Law, Office of the Attorney General, Jan. 2000, available at http://www.ecy.wa.gov/pubs/0011012.pdf. - Pomeroy, John Norton and Henry Campbell Black. A Treatise on the Law of Water Rights (2008). - Reisner, Marc and Sarah Bates. Overtapped Oasis: Reform or Revolution for Western Water. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1990. - Sax, J.L. et al. Legal Control of Water Resources: Cases and Materials. 4th ed. 2006. - The Water Report: Water Rights, Water Quality and Water Solutions in the West. http://www.thewaterreport.com/ - Bibliography on water resources available at http://www.ppl.nl/index.php?option=com_wrapper&view=wrapper&Itemid=82. The End