doc

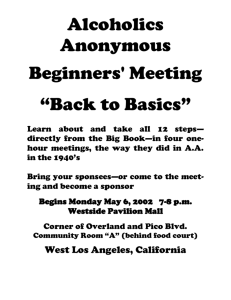

advertisement