9 - Article

advertisement

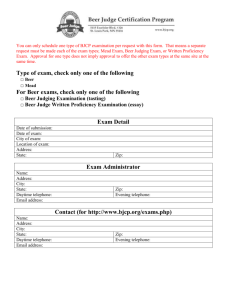

A Sommelier's Essential Beer Knowledge The following feature is co-written by Drew Larson and Sayre Piotrkowski, two Certified Cicerone ® beer directors based in Chicago and Oakland, respectively. With beer pairing dinners taking place at Michelin rated restaurants, craft-beer festivals featuring celebrity chefs, and people like Ferran Adria and James Syhabout creating proprietary brews, the integration of craft-beer into our contemporary culinary culture is taking off. Those of us who have been championing the cause of beer professionally are naturally thrilled at all of this. Even the most wine-centric Sommelier would likely agree that our guests benefit when we are able to utilize every possible tool at our disposal to enhance their experience. Today, as many ambitious Sommeliers are integrating craft beer into the experience they offer to guests, we are beginning to see craft beer climb out from its status as perhaps the most underutilized of these tools. The purpose of this piece is to provide you with our perspective, as beer-focused beverage industry professionals, watching this integration process unfold. What are some strategies we have seen that work well? What are the common mistakes we see being made? We hope to make clearer the ways in which a properly implemented beer program can help a restaurant generate larger profits and create a more complete experience for the diner. Hopefully we can provide you with a few ideas to consider when incorporating craft beer into a comprehensive restaurant beverage program. © Grant Kessler Composing a Focused and Fresh Beer Selection In our world, beer programs tend to market themselves by their size. The number of taps or bottles available often becomes the defining factor rather than any specific character or focus within the program. For example, the Hopleaf in Chicago boasts nearly 400 different bottles and 65 taps, while Monk’s Kettle in San Francisco carried and rotated over 700 different bottles on their menu in 2011 alone. As a result we have seen many proprietors and/or beverage managers think that the shortcut to a great beer list is to stock a large variety. This is a mistake and will quickly cause some obvious problems with respect to server knowledge, customer confusion, beer freshness, and manageability from a P&L perspective. The Hopleaf and Monk’s Kettle are in very specific markets and focused on a certain clientele, so their respective programs work. However, they invest in ensuring the aforementioned problems are not problems. Most restaurants will do better with very small, yet focused, beer programs. Just like any wine list, a good beer selection should have an identity. Have a reason for carrying each beer that you do. Even a small selection of 10 beers can be enough, provided you’ve focused your choices on the beers that make sense with the food you serve and the character of your establishment. Keep the size of your inventory small enough so that servers can wrap their heads around it; every beer you carry should sell quickly enough to ensure that you are pouring the freshest batch available. While there are a few exceptions, most beer is highly perishable. This is something to consider when composing your selections and ordering product. Over-stocked beer sitting around should stress out a bar manager in the same way that unsold produce bothers a chef. However, while the chef can see when the produce is bad, you and your servers may not realize that the pilsner you are serving is past its prime. Unfortunately, whether consciously or not, your guests will notice and likely not reorder. If your restaurant doesn’t sell that much beer, you might consider buying smaller kegs and/or selling those drafts in smaller pours and trimming the number of brands you offer. On the other hand, an improved beer program will see improved beer sales and product turnover. Glassware, Refrigeration, and Beer Temperature Chilled--or even worse, frozen--glasses are not the way to go. This is one of those things that makes every beer guy or gal cringe. No chilled glasses. Please, let us reiterate this: NO chilled or frozen glasses. It is unnecessary, wasteful, and detrimental to the quality of the beer you serve to your guests. Firstly, pouring beer into a frozen mug can create a micro-layer of frozen beer on the walls of the glass. As some of the water in the beer freezes the remainder of the beer's flavor will be thrown out of balance. Furthermore, as the glass warms this micro-layer of ice will be dumped back into the beer, again upsetting its balance. During the heyday of the American Light Lager in the 1970s and 80s, freezing cold was the order of the day. Even today we still see commercials talking about ice-cold beer in cans that promise to turn color when they are cold enough, meaning this perception is still something we fight against for truly quality beer. Cold temperatures mute the flavor and aroma of beer just as they do with wine. As a matter of fact, aren’t cold temperatures sometimes used to hide the poor quality in a wine? Same thing is true with beer. If you let a supermarket American Light Lager (you know the ones we are talking about) warm up, it tastes terrible. On the other hand, allowing a high quality craft beer come up to 45°-55° will help to release subtle aromas and allow more of its flavor to come across on your palate. The desire for chilled or frozen mugs stems from a belief that colder beer is better beer, and this is simply untrue. Should you find that the beers on your list are improved by being served ice-cold, the time has come to re-evaluate your selections. Another argument for keeping glassware out of your reach-in coolers is the fact that, from both a hardware and an energy costs standpoint, refrigeration is expensive. How many places have you worked that could boast an abundance of cold storage space? Probably not many. So why are we wasting this resource on things that do not need to be cold? The worst offenders are the bars or restaurants wherein the pint glasses get refrigerated, and bottled beer back-stock is exposed to high temperatures in a dry storage area. This is completely illogical and the sort of thing that gives a brewer nightmares. One frequently raised argument for placing glassware in a reach-in fridge is that the dishwasher delivers glasses that are hot to the touch and the fridge is a quick and easy way to counteract this problem. You are now expending even more energy and money in order for the cooler to bring itself down from increased internal temperatures. Should you find yourself experiencing this issue, a glass rinser is cheaper to install and cheaper to operate than a “glass fridge.” A cold-water rinse just before use provides more than enough cooling to prepare a glass for beer and also helps to ensure your glass is “beer clean.” A final point to consider here is the selection of your glasses. The same beer will show differently depending on the style of glass in which it is presented. Just as there is a difference between a glass designed for a young New Zealand white wine and one designed for vintage Burgundy, most every beer style has an associated piece of glassware. While companies like Riedel have created a glass for every conceivable wine style, in the beer world it is the breweries themselves that often produce the ideal drinking vessels for their various brands. However, just as most restaurants (with the exception of the super-elite) only use 2 to 4 different wine glasses in day-to-day service, most would do just fine with a pint glass, a tulip glass, and a goblet for beer service. These three standard styles of glassware will cover nearly the entire spectrum of potential beer styles. Hopleaf's glassware selection © Grant Kessler How to Get the Right Beer for a Guest Often customers who are apathetic about ordering unfamiliar beers from a menu--or even having a beer at all--are weary because they haven’t gotten what they asked for in the past. This is not to say that a server brought them something other than what they had ordered, but rather they thought they had requested something dark and sweet, and received a recommendation for something red and bitter instead. If we ask a Sommelier for something red, chewy, tannic, and fruity to go with a steak, he or she will likely already have 15 suggestions. However, how many diners order wine with that kind of clarity? How many of your guests actually know what tannin is, or what you might mean by describing a wine as “earthy?” In the trade we have all learned how to ask questions and “read” guests in order to better guide them toward the proper selection; the need for such a process is just as common with respect to beer. You may encounter a guest who says something like, “I am just not into hoppy beers,” and then, in his or her very next breath, says something completely contradictory, like “I love the Sweetgrass APA from Grand Teton.”--a very hoppy American Pale Ale. For this reason, you might consider training your staff to ask questions like, “What do you want your beer to taste like?” and, “Can you remember the last beer you loved?” We find that this can be much more effective technique than asking about styles, or restricting the conversation to beer specific terminology like “malty” or “hoppy.” As in the wine world, such “insider” terms are frequently misunderstood, even among customers who fancy themselves knowledgeable on the subject. It is also generally a wise move to avoid use of the word “light.” This is a classic example of a term that means something different to every beer drinker. For some, “light” indicates a mildness of flavor; for others it may indicate a low level of alcohol or calories, or a dry texture, or for others a pale color. In our experience it is best to keep the conversation related to familiar specific descriptors: sweet vs. bitter, rich vs. dry, high alcohol vs. low alcohol, and so on. Just as with wine, the trick is to find ways to get your guests speaking in terms that are familiar but also specific. The Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) publishes a free guide produced in conjunction with the Brewer’s Association that outlines all of the “accepted” styles of beer. This guide can be printed, ordered in hard copy, or even put on your smartphone as a free app. In order to get the right beer into the hands of each guest, a Sommelier should really know and understand their beer list, and the list should be logically organized. A beer list could be short, with products organized from mild to intense, or long, with options listed by country or style. If the list has a logical and natural order to it, it makes understanding easier for both the staff and guests. The BJCP guidelines can aid in this organization and give the sommelier a better understanding of beer styles. Once you know what your beer IS, you will be better prepared to find a perfect beer for each guest. Consider Beer in Pairing While we may come from establishments where beer is the primary beverage focus, we know that for most of you a good beer program is one that will support and complement your wine program. Such a selection provides delicious and interesting beer choices for devoted beer drinkers and adventurous diners looking to try something different, while also seeking to raise check averages by utilizing beer as both an aperitif and as a useful pairing asset for items that may not work as well with wine. Today restaurants often seem to be reaching for craft beer with cheese courses, charcuterie, raw bar items and dessert. This strategy leaves the main courses open for wine sales and serves as a great example of how a fully integrated beer program can add to both a guest’s enjoyment of their experience and to a restaurant’s bottom line. Locavore Meets "Loca-Pour" Since terroir does not dominate brewing the way it does winemaking, it is possible to produce beers of almost any character anywhere on the planet. There are a few notable exceptions to that statement, but they are beyond the scope of this piece. In most major markets it is possible to find a significant portion of the spectrum of potential beer characteristics within the portfolios of your local breweries. This negates the need to source draft beers from across the globe. As an example, consider this selection from a newly-opened Bay Area establishment. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. A Bavarian Style Hefeweizen A Pre-Prohibition American Pilsner A Wallonian Style Saison An Amber Lager A British Style Brown Ale An IPA A Stout A Sour Beer All of these beers are brewed within the state of California, yet this concise and 100% locally-sourced list offers guests a significant portion of the potential beer spectrum. Draft vs. Bottle In most non beer-focused restaurants draft lines are scarce. These lines should be saved for beers that truly benefit from draft dispense. Aside from price, the primary benefit of draft dispense is freshness. There are a few beer styles in which freshness is particularly critical. These include almost all contemporary IPAs, Pale and Amber Ales, and any other beer that is “dry-hopped.” Dry-hopping is a process by which hops are used as post-fermentation aromatizers. These aromatic compounds begin to break down immediately as the beer is racked off of the hops. From here it is a matter of weeks--not months--before the beer is significantly less appealing aromatically. Conversely, two styles we often see sommelier-run beer programs emphasizing do not benefit at all from draft dispense; Belgian-style Abbey Ales and Hefeweizens. These feature higher volumes of dissolved CO2, with recipes calibrated toward bottle conditioning and the intentional lack of filtration. These factors actually contribute to a beer that will suffer on tap. Many of the classic bottle-conditioned Belgian imports are not even offered in kegs. These beers tend to benefit from time in the bottle and particularly durable examples have the potential to mature beautifully for years with proper storage in a dark place no warmer than 60°F. Hefeweizen is another special case. While common commercial examples are seldom meant to age, Hefeweizen underwhelms on tap. A true Hefeweizen is dependent on the integration of its lees to achieve its signature texture, flavor, and aroma. As modern keg designs feature a down-tube that causes the beer to dispense from bottom of a keg first, any solid matter that has fallen to the bottom of the keg will be released in the first few pints. You will soon be selling a beer that is lacking its most characteristic element. The bar at Hopleaf © Grant Kessler Service Standards for Beer In a wonderfully welcome sight for any devout beer-drinker, a Sommelier serves beer as though they were pouring a 61’ Cheval Blanc in a fine dining restaurant, carefully watching the neck of the bottle to ensure that the beer was poured off its sediment if necessary. Sadly this is a rare occurrence and most wine-centric restaurants remain notoriously neglectful of beer service standards. The experience of being the one beer drinker at a table full of savvy and eager wine drinkers can be a lonely one. We feel like an unwelcome inconvenience even when we are members of a party that is receiving excellent service on the whole. If you are going to make beer a component of your beverage program, the goal must be to make your beerdrinking customers feel as special and as attended to as wine drinkers. Customers have a right to expect that their beer will be served at the proper temperature, in the proper glass, and that it will be poured in the proper manner for the style. While you don’t need to be an expert on these standards for all the beers of the world, it is entirely reasonable for a guest to expect that you and your staff are familiar with these standards for beers you’ve chosen to carry. When a beer is ordered let your guest know that his or her beverage choice is just as important as everyone else’s by placing the beer drinker’s glassware as you place stems for the wine. Bring the beer bottle to the table separately, opening and pouring just as you would in wine service. These simple gestures will help to create an environment where a beer drinker does not feel like an outcast. Couple that with a compelling selection and you might be surprised to see us returning frequently with like-minded friends. Some Useful References Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) A good link to style guidelines as discussed. http://www.bjcp.org/stylecenter.php Cicerone ® Program An educational and certifying body started by Ray Daniels and designed to create the equivalent of Sommeliers for beer. At only 4 years old the program already counts Certified Beer Servers in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, each of the Canadian provinces and a range of other countries including Australia and Britain. This program has 3 levels, the first of which is Certified Beer Server and is a great way to impart useful floor service standards for service staff. The program is preparing to grow even larger with European and Canadian chapters and a new online learning forum. http://www.cicerone.org/ Brewers Association: Draught Beer Quality Manual This is fantastic reference (pdf) discussing draught systems and is now considered the industry standard. This outlines very simply the equipment your draught system uses, when and how it should be cleaned, and how to troubleshoot problems. Do you know how much money you're throwing away when you pour foam down the drain? http://www.draughtquality.org/w/page/18182201/FrontPage Tasting Beer: An insider’s Guide to the World’s Greatest Drink by Randy Mosher This is a fantastic one-stop-shop book on beer. It discusses history, styles, serving, care, and food pairing. While there are dozens of incredible beer books, this one is a great overall reference. http://www.amazon.com/Tasting-Beer-Insiders-WorldsGreatest/dp/1603420894/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1335196819&sr=8-1 Drew Larson grew up with such an affinity for food he had his own vegetable garden as a young child. After graduating from Western Illinois University, he became an officer of the United States Army, flying Blackhawk helicopters for the Army Medical Department. During his 18 years of service he traveled all over the world gaining a true and deep passion for the culture of foods and beverages. After leaving active duty, he followed his enthusiasm for food to Kendall College of Chicago earning a degree in Culinary Arts. Throughout his travels and culinary training he found that his passion for beverages was limitless. Drew has been brewing beer for 12 years and is a Certified Cicerone ® (Beer Expert), is studying to take the Master Cicerone ® test, and has guest lectured on beer at Kendall College’s culinary program. Drew furthered his beverage studies by attending the intensive wine program at The French Culinary Institute in conjunction with the Court of Master Sommeliers where he earned his Certified Sommelier Certificate and also took and passed the Certified Specialist of Wines certificate with the Society of Wine Educators. Currently, Drew is the beverage director at Michael and Louise’s Hopleaf Bar in Chicago; an internationally renowned Belgian beer bar (also a Michelin Guide Bib Gourmand Restaurant) boasting a current selection of almost 400 different beer bottles, 65 beer taps, 60 bottles of wine, and 8 wine taps. In addition he works as an Associate Ambassador to William Grant & Sons family of spirits, which includes Balvenie and Glenfiddich Scotches, Milagro Tequila, and Hendricks Gin and will soon earn his Certified Specialist of Spirits certificate from the Society of Wine Educators. Follow Drew on Twitter at @drewdlarson