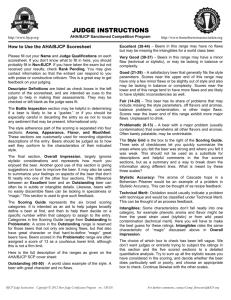

How_to_Judge_Beer

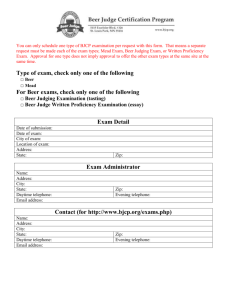

advertisement