Salience and Frequency of Meanings

advertisement

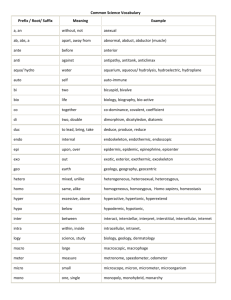

Salience and Frequency of Meanings Comparison of Corpus and Experimental Data on Polysemy Daniela Marzo, Verena Rube, Birgit Umbreit (University of Tübingen) Corpus and Cognition Workshop, Corpus Linguistics Conference 2007 Structure 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Hypotheses Evidence from other studies Production experiment Corpus analysis Comparison Résumé 2 1. Hypotheses Hypothesis 1: Frequency = Entrenchment (≈ Salience) Schmid (2000): From-Corpus-to-Cognition Principle, compare: Langacker (1991) 3 Hypothesis 2: Frequency ≠ Salience (Gernsbacher 1984, De Mauro 1980) 4 2. Evidence from previous studies Roland & Jurafsky (2002), Gilquin (2006 and 2007) - comparison of corpus studies and experiments on polysemy → differences in verb sense distributions → Evidence against Hypothesis 1 5 - But Gilquin (2007) claims that there are some links between salience and frequency: If phrasal and colloquial meanings are excluded from her analysis of to take, the ‘move’ sense is most prominent in the corpus and in the experiment. 6 - Gilquin (2007) also claims that the prototypical (= most salient) sense has to be a concrete sense. 7 3. Production experiment Sentence Generation Task (SGT) Subjects are asked to produce sentences disambiguating the meanings of the stimulus (Caramazza and Grober, 1976; Colombo and Flores d’Arcais, 1984; Raukko, 2003) Definition Task (DT) Sentences should be accompanied by definitions (Raukko 2003) 8 Questionnaire 9 Example: Disambiguation by sentences (1) Quel bimbo diventerà grande in fretta (crescere). This child will get big very soon (to grow). (2) Ha un grande appartamento (di vaste dimensioni). He has got a big apartment (of big dimensions). 10 Example: Disambiguation by sentences Two closely related meanings - ‘spatially extended’ - ‘tall, extended in height’ were disambiguated by the informants. 11 Example: Disambiguation by definition (3) Quel cantante è grande. This singer is ?. Occurrence is ambiguous: 1. ‘tall, extended in height’ ? or 2. ‘admirable, famous’ ? or 3. ‘very able, very gifted’? 12 Example: Disambiguation by definition The definition disambiguates the sentence: Quel cantante è grande (famoso). 2. ‘admirable, famous’ 13 Comparison sample 400 stimuli 20 stimuli per questionnaire 30 informants per questionnaire Comparison sample: Results for the 15 most frequent words: andare, avere, cosa, dire, dare, dovere, essere, fare, grande, potere, sapere, stare, vedere, venire, volere 14 4. Corpus Analysis (CA) Corpus of the Lessico di frequenza dell‘italiano parlato (LIP) - - - Corpus of transcribed spoken language easily accessible via the banca dati dell’italiano parlato (BADIP) ca. 490000 words 5 different types of oral texts: telephone conversations, university lectures, etc. recordings were made in 4 Italian cities: Florence, Milan, Rome and Naples. 15 Constituting the Subcorpus For each of the 15 sample words: 50 randomly selected occurrences of the Florence subcorpus (10 per text type) ~ average number of sentences in the SG&DT Only occurrences of the original stimulus! (No idioms, etc.) 16 5. Comparison (i) The most salient meanings in the SG&DT in the majority of the cases (9/15) correspond to the most frequent meanings of the CA. venire, andare, dire, dovere, essere, fare, potere, sapere, vedere 17 Comparison for sapere 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Experiment Corpus . t . f ll g sth d ou o sth stand ean te o sme uage st to uous anin w e s m r to in d o ta to lang att big me kn to f e to unde o t to am ew o f# t bl to o n a e nd no b a m to om c d oo g a ve a h to 18 Comparison for essere 50 40 30 20 10 0 Experiment Corpus s NM c ) ti tyj)ec te) red) e ofe ase anng toc ost x isiton)al lepdpensureher) ti ong)ouN i t s e n i m a t a i s ter(i dect obewehmea sa mto be lo to toofesbetoc hame(weaindi camb c ra e a m b h tobe e to (pr to ha to abb setr (s o to be t e c o + tim b t + b + o ( t to e ted ( to e( b b to oc a to l be to 19 (ii) If the most important meaning in one data type does not correspond to the most important meaning in the other data type, it is likely to correspond to the second most important meaning. Sometimes this works in both directions. cosa, avere, dare, grande, stare, volere 20 Comparison for grande 40 35 30 25 20 15 Experiment Corpus 10 5 0 t s s e p d n un ing ted ou ag ee guou tio si ty nde o n n d a # / an m e e m u i e l a h e t t t f g i b a a i g n m S b ~ # ex ,t hi ,i am le ig ed l ly ew e# t act b b l a n f r i i a t b t g a no bs mir suita sp be #a ad o t g bi 21 (iii) The less frequent meanings in the CA and the less salient meanings in the SG & DT usually diverge. 22 Comparison for essere 50 40 30 20 10 0 Experiment Corpus s NM c ) ti tyj)ec te) red) e ofe ase anng toc ost x isiton)al lepdpensureher) ti ong)ouN i t s e n i m a t a i s ter(i dect obewehmea sa mto be lo to toofesbetoc hame(weaindi camb c ra e a m b h tobe e to (pr to ha to abb setr (s o to be t e c o + tim b t + b + o ( t to e ted ( to e( b b to oc a to l be to 23 Importance of concrete meanings In the cases of result (ii): Experiment: most important meaning = “concrete” meaning Corpus: most important meaning = “abstract” meaning e.g. cosa Corpus: ‘object #abstract’ 84 % Experiment: ‘object #concrete’ 39 % 24 ⇒ confirmation of the claim that the “prototypical” sense is a concrete sense ⇒ the importance of concrete meanings in the cognitive system seems to inhibit the total matching of the results 25 5. Résumé The comparison study confirmed No 1:1 correspondence between experiment and corpus data ⇒ frequency ≠ salience (Hypothesis 2) BUT: In almost two thirds of the data the most important meanings in CA and in SG&DT are identical. If they do not match there is correspondence to the second most important meaning. ⇒ frequency ≈ salience (Tendency towards Hypothesis 1 ?) 26 Comparability of the evidence? Production Corpus task data = language reflection data data = language use data 27 THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION! 28 References Caramazza, A. and E. Grober (1976) Polysemy and the structure of the subjective lexicon, in C. Rameh (ed.) Semantics: Theory and Application. Georgetown University Round Table on Linguistics 1976, pp.181-206. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. Colombo, L. and G. B. Flores d’Arcais (1984) ‘The meaning of Dutch prepositions: Psycholinguistic study of polysemy’. Linguistics 22, 51-98. De Mauro, T. (1980) Guida all’uso delle parole. Come parlare e scrivere semplice e preciso. Uno stile italiano per capire e farsi capire. Roma: Editori Riuniti. De Mauro, T. and F. Mancini (1993) Lessico di frequenza dell’italiano parlato. Milano: Etas Libri. Gernsbacher, M.A. (1984) ‘Resolving 20 years of inconsistent interactions between lexical familiarity and orthography, concreteness, and polysemy’. Journal of Experimental Psychology 113, 256-81. Gilquin, G. (2006) Towards an empirically grounded definition of prototypes, Poster Presentation at Linguistic Evidence II, Tübingen, 2 4 February 2006. 29 References Gilquin, G. (2007) Universality and language specificity in prototypicality. Paper presented at the AFLiCo conference, Lille, 10 -12 May 2007. Juilland, A. and V. Traversa (1973) Frequency dictionary of Italian words. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter. Langacker, R. W. (1991) Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. II. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Raukko, J. (2003) Polysemy as flexible meaning: experiments with English get and Finnish pitää, in B. Nerlich et al. (eds.) Polysemy: Flexible Patterns of Meaning in Mind and Language, pp. 161-93. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Roland, R. and D. Jurafsky (2002) Verb sense and verb subcategorization probabilities, in Stevenson, S. and P. Merlo (eds.) The Lexical Basis of Sentence Processing: Formal, Computational, and Experimental Issues, pp. 325-46. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Schmid, H. J. (2000) English Abstract Nouns as Conceptual Shells. From Corpus to Cognition. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 30