Absence management - Australian Public Service Commission

advertisement

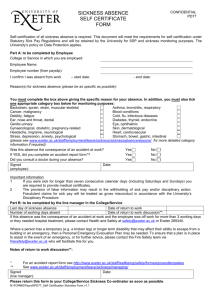

Issue 4 Absence management May 2012 APS Human Capital Matters: Absence Management May 2012, Issue 4 Editor’s note to readers Welcome to the fourth edition of Human Capital Matters for 2012—the digest for time poor leaders and practitioners with an interest in human capital and organisational capability. This edition focuses on the challenges of absence management within the public sector and between sectors. Better managing absence and increasing attendance rates has been a long-standing issue for the APS. The Australian National Audit Office’s ‘Absence Management in the Australian Public Service’ is provided a substantial review of absence across the APS (Performance Audit Report No. 52, 2002–03, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2003). The lack of a universally accepted definition of workplace absence in the APS led the ANAO to use the term ‘unscheduled absences’. The ANAO report offered no precise definition of absence, other than this dual typology—‘involuntary and unavoidable’ and ‘voluntary and avoidable’ (pp. 31–32). In 2005–06, the APSC consulted widely with APS agencies around absence management practices and developed APS-wide benchmarks that are reported through the State of the Service report, and two companion documents: Fostering an Attendance Culture: A Guide for APS Agencies (2006) and Turned Up and Tuned In: A Manager’s Guide to Maximising Staff Attendance (2006). An important contribution of Turned Up and Tuned In is the definition of workplace absence as: Absence from work in recognition of circumstances that can generally arise irregularly or unexpectedly, making it difficult to plan, approve or budget for in advance, and which is inclusive of planned medical procedures. Better managing absence and increasing attendance rates is central to improving agency capability. Absences from the workplace limit workforce capacity in terms of employee availability (how many people are available to complete the work) and performance (how productive people are at work). To sustain capability it is important that agencies have a good evidence base for understanding the of absence, a good understanding of what influences absence behaviour in the workplace, and a thoughtful and targeted approach to response to managing the issues. The articles in this issue of Human Capital Matters include cost analyses of sick leave behaviour and management in the US, Europe, the UN, and across the UK private and public sectors. A strong case for the non-financial benefits of absence management in the UK Civil Service is outlined in a report by Accenture. There is a forward looking paper arguing that changes in technology require a rethink of how workplaces manage absences. And, finally, a guide to six principal absence management challenges facing the modern workplace and several ‘strategic approaches’ to dealing with these. About Human Capital Matters Human Capital Matters seeks to provide APS leaders and practitioners with easy access to the issues of contemporary importance in public and private sector human capital and organisational capability. It has been designed to provide interested readers with a monthly guide to the national and international ideas that are shaping human capital thinking and practice. 2 Comments and suggestions welcome Thank you to those who took the time to provide feedback on earlier editions of Human Capital Matters. Comments, suggestions or questions regarding this publication are always welcome and should be addressed to: humancapitalmatters@apsc.gov.au. Readers can also subscribe to the mailing list through this email address. Accenture, ‘Absence Management in the Public Sector’ (Accenture Leadership Series), UK, 2010, 23 pp. This report is one of a series designed to address crucial challenges facing the UK’s public sector—in this case employee absenteeism—a problem acknowledged by government to be one of ‘prime importance’. Absenteeism has a significant negative effect on the national economy and, at the local level, on the public sector’s ability to deliver the consistent, high-quality public services citizens expect. In 2009, for example, the direct loss to British employers in all sectors from absenteeism was £16.8 billion; additional indirect costs were incurred equating to £465 per employee per year—for both the public and private sectors. The direct cost of public sector absence each year is around £5.5 billion and the combined direct and indirect costs annually total some £9.3 billion. The incidence of employee absence in the private sector is generally lower than that in the government sector—in 2010, an average of 5.8 days per year per employee in the private sector and 8.3 days per year per employee in the public sector. On 24 May 2010, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the newly-elected Coalition Government, Mr George Osborne, announced that better absence management across the public sector could make a major contribution to the Government’s £6 billion savings program. The report argues that effective absence management has extensive benefits other than just the financial. It has the potential to improve productivity and employee wellbeing and drive down costs—directly or indirectly—in four areas: 1. Organisational costs—direct (for example, salary bill) and indirect (for instance, medical costs, cover for absent staff and management costs). 2. Employee costs—direct (for example, reduction of wage) and indirect (for instance, increased stress). 3. Impact on customer service—indirect; and 4. Impact on the organisation’s performance—indirect. The report sets out 15 initiatives and/or approaches implemented by public sector organisations which have already proved effective in reducing these costs and addressing absence management challenges (p. 12). These include: increased compliance by organisations with legislative obligations thereby reducing litigation risks; and a more trenchant understanding of absence which allows organisations to institute better targeted measures for assisting long-term or frequent absentees in a timely manner. Accenture’s wide-ranging work with absence management in the UK has revealed that no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to the issue of unjustified absence exists; however, the report identifies five ‘building blocks’ that in Accenture’s experience are effective in addressing the problem (pp. 15–16): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Board-level commitment and tracking of absence management. Clearly defined absence management policies and procedures. Training and support for line managers. Effective management of third-party suppliers. Standard absence management data/management information (MI) collection and monitoring across the organisation. 3 Accenture is a global management consulting, technology services and outsourcing company employing some 240,000 people working in more than 120 countries. Dame Carol Black and David Frost, ‘Health at Work—An Independent Review of Sickness Absence’, HMSO, London, November 2011, 112 pp. In February 2011, the British Government announced that Dame Carol Black and Mr David Frost would undertake an independent review of the sickness absence system in Britain. Some 150 million working days are lost in the UK each year due to sickness absence alone— approximately six days for each British employee. In most cases people are able to make a swift return to work; however, over 300,000 people do not do so and become (often long-term) recipients of health-related state benefits—the cost of which has reached some £100 billion annually. The principal aims of the review were to reduce the numbers of people needlessly moving out of work to long-term reliance on the benefits system and to improve ‘the coherence, effectiveness and cost’ of existing sickness absence arrangements. The review made 13 recommendations for change, 11 of which relate to supporting employees at work and the remainder to improving the benefits system. Among the former was a call for the establishment of a new Independent Assessment Service (IAS) which would provide in-depth assessment of an individual’s physical and/or mental function. The IAS would also give advice on how an individual on sickness absence could be supported to return to work—a service to be made available when an individual’s absence has lasted around four weeks. Chapter 4 of the report (pp. 53–63) deals with public sector absence. The sector employs about 20% of Britain’s total workforce; the review found that sickness absence levels vary considerably between public sector organisations with larger departments and agencies (i.e. those employing 500 or more staff) having higher sickness absence levels than medium and small ones. The authors recommend that the Government take ‘immediate action’ to bring the worst performing parts of the public sector up to the standards of the best. Ways of doing this which the review recommends include adopting examples of absence management best practice from the private sector and elsewhere in the public sector; greater senior leadership commitment to reducing absence; and introducing reward mechanisms and accountability for all managers responsible for managing and/or monitoring sickness absence levels. Appendix D to the report (pp. 103–109) discusses international approaches to dealing with sickness absence—‘a taxonomy of sickness and disability systems’. The report identifies three approaches to sickness management for working age individuals. The first, dubbed the ‘libertarian’ (e.g. in place in the USA, Canada, Australia) places the onus strongly on the individual to provide their own sick leave by drawing on that accrued during their working life. The second approach—at the opposite end of the scale—is that pursued in the Nordic countries. In this instance, more financially generous sickness payments are made and for longer periods than in North America and Australia. The third approach—one in place in the Netherlands— places a heavy burden on employers alone to finance long periods of recuperation and/or rehabilitation (for the first two years at 70% of earnings). The authors argue that all three approaches have advantages: a libertarian system works well for those who are part of it (especially long-serving employees); a statist system can provide a good safety net for all; and an employer-based system can potentially internalise sickness costs very well. However, each also has disadvantages: a libertarian system excludes many of the most poorly paid; a statist system places significant cost on the actor least able to alleviate the problem, that is, the State; and an employer-based system encourages doing the bare minimum and also results in high-risk individuals struggling to find employment. 4 Dame Carol Black is the UK’s National Director for Health and Work; David Frost is Director General of the British Chambers of Commerce. Nikolay Chulkov, Gerard Biraud and Yishan Zhang, ‘The Management of Sick Leave in the United Nations System’, United Nations, Geneva, 2012, 21 pp. Between February and November 2011, the Joint Inspection Unit (JIU) of the United Nations (UN) conducted a review of sick leave management arrangements across UN bodies. It evaluated the manner in which international organisations record, manage and report sick leave and proposed improvements that should enable the UN system to clarify, improve and harmonise system-wide, the rules and regulations pertaining to sick leave, prevent abuse and more importantly, fulfil the UN’s duty of care with regard to the health and safety of staff. The authors make a number of recommendations designed to improve administration of sick leave. They also emphasise the necessity for managers and supervisors to be formally trained in how to respond to the needs of staff with medical problems (including mental health issues) that may affect their performance and lead to lengthy absences or require short-, medium- or longterm adjustment to work schedules. In this connection, Recommendation 4 (p. 12) calls for the Executive Heads of UN organisations, in consultation with their respective human resources departments and the relevant health services, to design and implement an absence management module aimed at assisting staff with supervisory or managerial responsibilities to better manage workplace absence. Although the authors focus on sick leave, they also discuss ways of reducing absenteeism. Two means of doing so are examined in the report. The first is flexible working arrangements (FWA), an approach in place across the UN in four manifestations: Staggered Working Hours; Compressed Working Schedule (ten days working in nine); Scheduled Break for External Learning Activities; and Work Away from the Office (telecommuting). It is the UN’s experience that FWA decreases instances of unscheduled absence—though the report makes clear that it has no comprehensive statistics which would indicate that FWA results in lower levels of sick leave absence. The second approach is based on the implementation of a newly-developed model of health and productivity management (HPM)—‘the integrated management of health and injury risks, chronic illness and disability to reduce employees’ total health-related costs, including direct medical expenditures, unnecessary absence from work, and lost performance at work’. Nikolay Chulkov, Gerard Biraud and Yishan Zhang work in the Geneva-based Joint Inspection Unit of the United Nations. Confederation of British Industry (CBI), ‘Healthy Returns? Absence and Workplace Health Survey 2011’, CBI, London, May, 2011, 35 pp. The report, which is sponsored by the global biopharmaceutical company, Pfizer, contains the results of the 24th CBI annual survey of UK workplace absence and health and wellbeing trends. It was conducted during January and February 2011, and encompassed private and public sector organisations employing over one million people. Key findings include: Average annual employee absence levels have fallen by more than a quarter since the 1980s. While absence levels remain higher in the public sector than in the private sector, 2010 saw the gap narrow. 5 Health issues are seen as the most common factor causing employees to fail to perform to their potential capacity at work. The vast majority of organisations (95%) have a formal absence management policy in place. Line managers play a central role in managing employees’ absence and their resumption of work, with return-to-work interviews emerging as the technique most widely rated as effective. Non-genuine sickness absence is believed to account for 16% of all working time lost to absence on average, at a cost of over £2.7 billion annually. The CBI found the public sector to have a much higher median absence cost per employee than the private sector—£1,040 compared to a private sector median cost of £710—a difference of 46%. As revealed in other surveys (e.g. Accenture’s discussed separately in this document), the larger the organisation the higher number of absence days recorded and almost invariably the higher the median absence cost. The CBI gives the following snapshot: 1–49 employees (£684 median cost per absent employee); 50–199 (£648); 200–499 (£672); 500–4,999 (£850); and 5000+ (£828) (p. 15). The CBI is the leading peak organisation for British industry; Pfizer is one of the world’s largest research-based pharmaceutical companies. Ellipse and Professor Cary L. Cooper, ‘Sick Notes’, London, February 2012, 16 pp. This report, which is subtitled ‘how changes in the workplace and technology demand a rethink of absence management’, sets out the findings of a survey of 1,000 employees and 250 Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) employing people across the UK. It is based on two sets of research: the first surveyed line managers (who generally have responsibility for absence management in SMEs); and the second was aimed at those whom they supervise. The report examines the main causes and effects of sickness absence and employee and line manager attitudes towards it. The authors conclude that, while technology is changing the way people work, absence management procedures have not kept pace with this trend, thereby creating serious welfare, management and productivity challenges. The report found that 26% of employees had stayed away from work—‘skived’—at least twice during the preceding year and 80% of respondents are still going to work when they are ill. The process for managing absence within SMEs is often ‘confusing, chaotic or poorly thought-out’. Seventy per cent of organisations rely on non-human resources functions (i.e. line managers) to deal with the problem; some 90% of line managers said that formal absence management procedures exist, yet 41% indicated that they did not follow them. The study also revealed that SME senior leaders are giving insufficient attention to addressing the work-life balance challenges that may be contributing to the high incidence of absenteeism, despite growing evidence that such attention is warranted; for example, 70% of line managers and 50% of employees surveyed thought that being able to work at home more often would reduce the hours lost to stress-induced sickness. However, the increasingly high level of technology-facilitated workforce connectedness may be a double-edged sword—generating increased productivity through home-based work but longer-term health problems due to fewer opportunities to switch off and relax away from workplace pressures. Eighty per cent of line managers agree that absence management affects an organisation’s ability to attract and retain employees; and 72% of employees indicated that the way an organisation treats its sick workers has an impact on their feelings for the organisation. This is especially the 6 case for 18 to 24-year-olds (85%) in contrast to those aged over 55 (63%). A mere 15% said this had no impact at all. The authors recommend five steps towards achieving better absence management: Ensure clear and simple procedures are in place to guide line managers and human resources areas in managing absence. Use technology to monitor trends. Maintain proactive contact with employees. Consider accessing external expertise when necessary. Foster a culture of employee engagement and consider introducing forms of flexible working. Ellipse is a specialist group risk insurer offering group life and critical illness insurance; Cary L. Cooper is Distinguished Professor of Organisational Psychology and Health at Lancaster University. Ilias Livanos and Alexandros Zangelidis, ‘Sickness Absence: A Pan-European Study’, Munich Personal RePEc Archive (MPRA), MPRA Paper No. 22627, May 2010, 21 pp. In this study, the authors examine the determinants of sickness absence in 26 European Union (EU) countries and their broader implications. They regard workplace absenteeism as a ‘labour market behaviour’, one much affected by demographic and workplace characteristics and institutional and societal conditions. The study identifies absenteeism trends in the EU and examines the main factors determining the level of individual sickness absence in these nations, using the European Union’s Labour Force Survey (EU–LFS) micro-data. Particular attention is given to gender differences and the role individual features and characteristics of employment contracts have in creating these absence disparities. This is the first investigation of sickness absence with a pan-European focus to enable analysis to occur at both the individual (demographic and workplace) and the multinational (institutional and societal) levels. The report found absenteeism to be at a higher level among women (especially those aged 26– 35), singles, blue collar workers, employees without higher education, shift workers and contractors. The sickness absence ratio across European nations also varies markedly. At one end of the spectrum are the Scandinavian nations with a sickness absence rate above 4%; on the other end are many Eastern European and Baltic countries (e.g. Bulgaria, Latvia) at below 1%. Other notable patterns include the seasonal variation of sickness absence within countries. In the winter and autumn months absence rates are higher than in the spring and summer months in certain countries (e.g. Austria, Denmark, Germany, the UK). The level of sickness absence increases ‘monotonically’ with age up to retirement age, though members of the 65 and over age group who remain at work generally exhibit a lower absence rate than those aged 56–64. The authors conclude by stressing the need for governments to take greater account of the financial and other costs of absenteeism in the short- and longer-term. Ilias Livanos is based at the Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick, Coventry, and Alexandros Zangelidis at the University of Aberdeen’s Business School. 7 Mercer, ‘Survey on the Total Financial Impact of Employee Absences’, Mercer (USA), Portland, OR, June 2010, 30 pp. The first such report, based on an online survey of all US sectors and conducted by Mercer and sponsored by Kronos, was published in October 2008. It focused comprehensively on the cost of workplace absences and determined that the direct and indirect costs were much higher than previously thought. The same survey was repeated in the spring of 2010 with similar results. In 2010, 276 organisations were surveyed. Health care employers constituted the largest proportion of respondents (22% of organisations); services comprised 15%; and public sector, government and public schools, 11.6%. The survey yielded six significant findings: The total costs of all major absence categories, including direct and indirect costs, average an equivalent of 35% of base payroll. The average total costs of incidental unplanned absences amount to 5.8% of payroll, and those for extended absences constitute 2.9% of payroll. The combined total costs of incidental and extended absences—the kinds of absences employers try to minimise— add up to 8.7% of payroll. The total costs for planned absences, such as vacations and holidays, average an equivalent of 26% of base payroll. Incidental unplanned absences result in the highest net loss of productivity per day (i.e. work that is not done or postponed by not being covered by others): 19%, versus 13% for planned absences and 16% for extended absences. To help manage incidental unplanned absences, 44% of organisations surveyed have Paid Time Off (PTO) banks that combine vacation and incidental sick days for non-union hourly workers, and 42% have them for ‘exempt’ employees (those granted greater flexibility under legislation to discharge their duties). The number of incidental unplanned absence days per employee per year averaged 5.4 days across all employee classifications. In order to address these issues, the report recommends that organisations focus on three approaches: 1) improve attendance and benefits policies; 2) enhance absence management and administration (e.g. streamlined processes, centralised recordkeeping and collation and review of data); and 3) tackle the array of causes underlying absenteeism—from workplace culture to ones external to the workplace. Mercer is a global human resources and financial services consulting firm operating in more than 40 countries and employing over 19,000 people; Kronos Inc. is a leading international management solutions company. TBX Benefit Partners, ‘Effectively Managing Employee Absence: Leveraging Internal and External Resources’, TBX Partners, Atlanta, Ga, Winter 2011, 9 pp. This concise but wide-ranging guide outlines six principal absence management challenges and details several ‘strategic approaches’ to addressing each of them. Challenge 1: Turning Data into Information (Many employers collect extensive employee absence data, but they often have few effective tools to consolidate these figures and convert them into methods of reducing absenteeism and improving productivity). 8 Challenge 2: Managing a Dispersed Workforce (Multi-location employers, although aware of the problems associated with managing a dispersed workforce, often struggle to develop a centralised approach to doing so; as a result human resources staff in the organisation’s different locations frequently develop their own absence management approaches, leading to inconsistencies throughout the organisation). Challenge 3: Avoiding the “Rubber Stamp” Mentality (Employers frequently view their attempts to increase employees’ efficiency through improved employee absence management as conflicting with their legal compliance obligations; however, a balance must be struck between these administrative challenges). Challenge 4: Tracking Intermittent Leave (Intermittent Leave poses a special problem for employers, arising from its frequency and the ongoing challenges for supervisors and human resources areas of tracking and recording it). Challenge 5: The Return on Investment (ROI) Objection (ROI for absence management is accurately quantifiable only on a retrospective basis, with the result that employers often struggle to develop a strong economic rationale to support the need for enhancing their internal absence management infrastructure or outsourcing the function to a third-party vendor). Challenge 6: Creating a Sustainable Process (Even employers who invest heavily in absence management strategies may notice over time that their effectiveness declines due to supervisor and employee turnover and other factors such as lack of consistent accountability processes). TBX Benefit Partners is a consultancy focusing on absence management advice and planning. 9