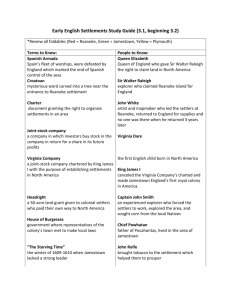

Stephen Hopkins

advertisement