- UVic LSS

advertisement

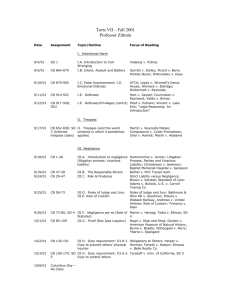

TORTS Final Outline – Winter 2014 (Galloway) Contents Negligence ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Duty of Care ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Commercial vs. social hosts ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Fetus cases ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Government cases – operational vs. pure policy decisions (per stage 2 of Anns test in finding a DOC) ........................................... 3 Recognized duties (categories are not closed) .................................................................................................................................. 3 Standard of Care .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Causation ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Remoteness ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Thin Skull Rule ............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 The Crumbling Skull Rule ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Novus Actus Interveniens (Intervening Act) ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Manufacturers, Distributors, Contractors and Remoteness – 3rd parties involved ........................................................................... 6 Defences ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Liability for Failure to Provide Information ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Duty to Warn.......................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Liability for Psychiatric Harm (Nervous Shock) .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Liability for Pure Economic Loss............................................................................................................................................................... 10 Negligent Misrepresentation ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 Negligent Misrepresentation and Negligent Provision of a Service .................................................................................................... 11 Negligent Supply of a Shoddy/Dangerous Product .............................................................................................................................. 11 Negligence A successful action in negligence requires that the π demonstrate (Mustapha): 1. ∆ owed him a duty of care 2. ∆’s behaviour breached the standard of care 3. π sustained damage 4. Damage was caused, in fact and in law, by the defendant’s breach. Includes: a. Damage caused in fact by ∆’s breach (“causation” - was ∆’s action a “necessary precondition” to damage?) b. Damage caused in law by ∆’s breach (“remoteness” of damage; causation in law) Duty of Care Duty is owed only to those within the orbit of danger as disclosed to the eye of ordinary vigilance (Cardozo in Palsgraf) - ∆ is about to act: contemplate who may be affected, in what way, and the level of risk? The fact that the ∆ ought not to ahead b/c 3rd party might be hurt does not entail that he ought not to go ahead b/c of the π Where eye of ordinary vigilance does foresee a risk, duty is owed to particular individuals (private, not public) Neighbour Principle underlies DOC (Donoghue) - (like Cardozo, emphasizes reasonable foreseeability) ***Duty is owed to your neighbour to avoid acts that you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure them*** Neighbour: persons closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to contemplate when acting Page 1 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic - Home Office v Dorset Yacht affirms applicability of the neighbour principle (unless reason for not doing so, i.e. policy, for reasonably foreseeable economic losses, or where no causation) Anns/Cooper Test (current mode of analysis) – to determine whether a DOC is owed in a “novel” case (Cooper) 1. Reasonable foreseeability + proximity >> prima facie duty π bears burden of establishing a valid cause of action and hence a DOC (Odhavji, cited in Childs) a. Foreseeability: act of wrongdoer reasonably likely to cause damage to the person harmed (neighbor)? Reduced capacity π (i.e. drunk): inability to handle situation >> ↑ foreseeability of injury (Jordan House) Intoxication alone ≠ foreseeable risk; must be additional risk factor (Stewart) b. Proximity: sufficient relationship of proximity where ∆ obliged to be mindful of the plaintiff’s interest in acting? Closeness and directness between parties >> Concerned w/ whether actions have a close/direct effect on π (rather than physical proximity) (Hill) A personal relationship (i.e. particular person? Discrete group?) is relevant but not determinative (Hill) More hesitant to find a DOC when it involves a more general relationship (Cooper) Private duty need not necessarily be personal (i.e. to all road users in Bolton) Look to: expectation, representation, reliance, nature of interest involved (mindful of π’s legit interests) I.e. Critical interest where freedom at stake: lends support to finding proximity (Hill) Three helpful themes on proximity – would it be just/fair to impose liability towards 3rd parties? (Childs): i) Intentionally inviting a person to an inherent risk that you create/control (like Crocker) ii) Paternalistic relationships: parent/child, captain/guests. One party is vulnerable – position of dependency Must be balanced w/ personal autonomy iii) Public function / commercial enterprise that includes implied responsibilities to the public at large Due to reasonable reliance Issue: public function doesn’t give rise to a tort just b/c people rely (Cooper) o May look at relevant policy factors at this stage 2. Consideration of residual policy factors: reason to negate prima facie DOC established? Once π establishes prima facie DOC >> burden to ∆ to show countervailing policy considerations (Odhavji, cited in Childs) o Policy concerns (fairness, deterrence, restitution) o Does the law already offer a remedy? o Does it create indeterminate liability (risk of unlimited liability to an unlimited class)? o Lack of control over risk is a weaker policy argument when case of physical injury rather than economic (Fullowka) o Floodgates? o Basic question: is it just and fair having regard to the relationship to impose a DOC? May be fair/just where you are the author of the risk o Effect of recognizing a DOC on other legal obligations, the legal system and society more generally Good Samaritan Act – no liability for emergency aid (*w/ exceptions) – see page 11 outline Misfeasance: actions which make the world a more dangerous place Nonfeasance: failure to negate dangers independently created Common law does not recognize that a stranger has any duty to come to assistance of another stranger. Duty may arise where relationships are recognized >> could give rise to duty to provide benefits to others Commercial vs. social hosts Social hosts do NOT owe a DOC to members of the public who may be injured by guest’s conduct (Childs) There is a precedent of a DOC owed by commercial host, BUT this is distinguished from a social host (Childs) 1. Monitoring ability (i.e. social host doesn’t know if a guest is going to the kitchen to pour another drink) o Training of alcohol servers in a commercial setting o You don’t check your autonomy at the door of a social party 2. Regulatory environment (i.e. diff. expectations from commercial establishments; bouncers/structure) 3. Incentive to over-serve in commercial establishments (i.e. more money in) Page 2 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic Fetus cases Paxton: Child born with abnormalities fits in one of 2 categories: 1. Caused by wrongful act or omission >> Doctor liable for damage 2. I.e. “But for Doctor’s negligence, I would not have been born” << not a recognized action in Canadian law (*policy) No DOC owed from Dr. to unborn child; rather, duty owed to their patient (mom), because: o Potential conflicting interests (between unborn child / mom) o Mother free to make informed choice, even with risks (*autonomy of women) o Insufficient proximity between Doctor and unborn child (necessarily indirect: “mediated” through patient) Liebig: Dr. owes DOC to infant during labor/delivery (legal status to sue only arises when child is born) Cherry: DOC owed to fetus not to cause it harm if abortion is unsuccessful (right only asserted upon birth) Government cases – operational vs. pure policy decisions (per stage 2 of Anns test in finding a DOC) Lewis: - - Gov’t may be exempted from tort liability through statute or in making pure policy decisions >> Held: gov’t is liable (operational decision requiring due care by gov’t in the highway’s upkeep; non-delegable DOC) Pure policy decisions (PPD) – Immunized from tort liability o Characterization relies on nature of the decision (not identity of the actor) o Grounded in social, economic, and pol’t considerations; discretion/weighing of factors (Imperial Tobacco) o PPD are generally made by persons of high level of authority (though not determinatively) o Budgetary allotments for gov’t are PPD, as a general rule o Decisions which are “part and parcel” of a gov’t policy decision (Imperial Tobacco) o NOTE – decision must not be irrational nor made in bad faith (which could lead to tort liability!) (Imperial Tobacco) Operational decisions – NOT immunized from tort liability (DOC applies) o Implementation of policy operationally Recognized duties (categories are not closed) Notion of precedence: case law develops categories of relationships which give rise to DOC [unnecessary to re-do test] (Cooper) Manufacturer-consumer o Duty to design and manufacture in a reasonable manner – reasonable care against defects (Donoghue) o Duty to warn about any dangerous aspects of their products (Smith v Inglis) UK: prison guards owe DOC to those in proximity to them to adequately supervise prisoners (cf Dorset Yacht) Owner/operator of a boat owes a duty to come to aid of passengers if they come into danger (i.e. fall overboard); general duty to consider own safety and that of their passengers (Horsley) Duty to rescuers as an author of risk: where own negligence induces rescue (i.e. by his fault created a situation of peril, or negligently attempted first rescue), as long as rescuer is not fool-hardy! (Horsley) Organizers of dangerous competition – duty to participants (not to allow participation when drunk) (Crocker) Commercial hosts have a positive duty to prevent injury to patron (Jordan House) o Commercial host duty extends to other motorists (3rd parties) that the patron might encounter (Stewart) Establishments which serve alcohol must either intervene in appropriate circumstances or risk liability, and this liability cannot be avoided where the establishment has intentionally structured the environment in such a way as to make it impossible to know whether intervention is necessary. Drivers owe a duty of care to other road users (Stewart) Security firm owes a DOC to miners (under their supervision) to take all reasonable safety precautions (Fullowka) Police owe a duty to particular subjects under investigation (to conduct investigation reasonably) (Hill) Chief of police owes a private law DOC to supervise (Odhavji) Mining (gov’t) inspectors owe a DOC to miners (Fullowka) – relied on legal advice, p. 18 outline Cricket club owes duty to class of road users (neighboring road) (Bolton) Employer owes duty of care to employees, to take reasonable precautions (Paris) Duty of tire-sellers to think of 3rd parties (bar sale if you know it will be used in an unsafe manner) (Good-Wear Treaders) Lawyers owe a DOC to beneficiaries to use reasonable care in preparing wills; may be held liable for negligence (Wilheim) Home-builders (construction) have a duty to take reasonable care to make sure they’re safe (Winnipeg Condo) Page 3 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic Standard of Care Standard of care in a nutshell is… (Ryan v Victoria): What would be expected of an ordinary, reasonable and prudent person in the same circumstances (Crocker) o Held responsible for one’s own incompetence: adult is held to an objective standard (Vaughan) Objective test intended to reflect ideal community standards Idea that person is only at fault when they could’ve done otherwise (Galloway: what if could not achieve?) CHILDREN Two-stage test to determine standard of care (Heisler) 1. Capacity to be negligent? Having regard to age, intelligence, experience and general knowledge/alertness, is the child capable of being found negligent? (*subjective - re: particular child) o A child who “lacks capacity to be negligent” (subjectively) will not be held liable o Perhaps child may not have capacity to apply precautions when undertaking an activity >> negligence could flow from undertaking activity in the first place (knowing of own limited capacity) 2. If yes: held to standard expected of a child of like-age, intelligence, experience (development ≠ linear) Exception: held to adult standard when engaged in “purely adult activities” (Pope) o Notion of ultra-hazardous activity (i.e. motor vehicle) o Rationale for lower standard: cannot guard against youthful imprudence even if warned (may even be hard to ascertain whether approaching risk is adult/child) >> interest in public safety o BUT: difficult to characterize an activity as adult vs. child (Nespolon) Driving (adult); dropping off at side of road / babysitting (not adult)? o Galloway: adult/child activity distinction may be somewhat arbitrary – but whether a child could’ve acted differently is valid (i.e. should they have asked an adult for help in Nespolon?) MENTALLY ILL (a subjective and personal inquiry) Should not be held to strict standard (i.e. no fault) when they have taken adequate charge of own situation (i.e. guarded against risk as possible; adequate notice – can’t guard against unexpected heart attack) (Fiala) o Tort system should not be distorted by robust compensatory goals (>> no liability where no fault) - What is reasonable depends on the facts of each case, including likelihood and severity of the injury risked (Paris) o Likelihood of a known or foreseeable harm Bolton (cricket case): greater care required when there is a stronger likelihood Substantial risk = reasonable possibility + more than a remote possibility of injury More people >> ↑ likelihood of some injury Just because it’s happened once, doesn’t mean it is foreseeable to continue to happen Entirely risk-free is too burdensome/impractical; social value may justify *some risk Only required to take action against reasonably foreseeable risks of harm (Stewart) i.e. relevant that 2 sober people at table (not required to call a taxi) o Gravity of that harm, and Regulate conduct with respect to severity of the threatened harm, taking special risk into account (Paris) o Burden or cost which would be incurred to prevent the injury (i.e. feasibility of safety measures -Rentway) Bolton: ↑ cost of remedial measures cannot justify a substantial risk which ought not be taken Duty to make it safe if inexpensive Rentway (faulty truck): cost of avoiding risk (and ultimate utility of the product) is considered and weighed against the probability of harm and severity of injury (in determining the standard of care) o May look to external indicators of reasonable conduct (custom, industry practice, statutory/regulatory standards) Burden of proof to establish customary practice is on the party raising the issue (Waldick) If custom is uncontestable, may just ask judge to take judicial notice (Waldick) Paris (one-eyed employee): π may show they are different from other members of the class, requiring a higher standard than the custom (more at stake in wearing goggles when someone has only one eye) Customs – not determinative but may be helpful (Waldick) Custom must still be found reasonable in order to be persuasive in negation of liability (Waldick) Custom does not simply oust a DOC owed by statute (Waldick) Page 4 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic Negligence may be inferred if ∆ doesn’t follow usual practice >> ∆ may rebut w/ evidence that they were not negligent (i.e. that cream wouldn’t have prevented dermatitis) (Brown) Expert Standards Consensus of experts in a field on reasonable conduct is highly persuasive (Warren) Judicial deference to expert standards unless offends logic/common sense, or gross error (Warren) Professional Standards Specialist must exercise degree of skill of an average specialist (*higher objective standard) (ter Neuzen) Dr. who follows standard practice will not be found negligent (court does not have expertise to override unless standard practice fails to include obvious/reasonable precautions readily apparent) (ter Neuzen) Professional standards are “strong evidence” but are not strictly determinative of standard of care; all of the circumstances must be considered (Kern) Statutory Standards No tort for breach of statutory duty; must bring action in negligence (Saskatchewan Wheat) But, a statutory standard may be useful in determining standard of reasonable conduct (Sask. Wheat) To support an action (for relevance), object of statute standard must be related to harm caused (Gorris) Compliance w/ statute ≠ preclude liability, but tends towards a discharge of duty where (Ryan v Victoria): The regulation is specific Facts at hand can be regarded as an ordinary case Less discretion granted in performance (b/c discretion requires care; i.e. required vs. authorized) The ordinary person - Used to determine how much respect you owe those with whom you’re in a relationship (NOT utilitarian or wealth-maximizer << economist view is inconsistent w/ relational nature of tort law). Learned Hand: Risk is unreasonable where: (seriousness of risk) x (likelihood of injury) > Cost of avoiding risk Take precautions where: (what you are risking) > Cost of avoiding risk - Side note: may be able to expose individuals to more risk in order to meet emergency needs (i.e. a firefighter speeding) Causation SCC: The “but for” test is the test for causation, subject to a fairness test (Clements) “But for” test: π must show on a balance of probabilities (more likely than not) that “but for” the negligence of the ∆, injury would not have occurred. I.e. negligence was “necessary to bring about the injury” (factual causation). o Apply BFT w/ robust pragmatic approach (more likely than not caused the injury? Don’t need proof for sure) (Snell) o Where π shows likelihood that ∆ caused harm, may shift onus of proof onto ∆ where they are in a better position to know the cause of the injury (i.e. Dr. in Snell) o Application in Clements: husband not held liable for motorbike accident where he overloaded weight + sped, because the accident would not have occurred but for the nail in the tire (cannot say his actions caused the injury) BFT is subject to fairness: where 2+ ∆’s and cannot prove which one did the “but for” action for sure >> it would be unfair to hold neither liable b/c π can’t prove on BFT >> apply the material contribution test (*only where 2+ ∆’s) (Cook v Lewis): o Where ∆’s both materially contribute to a result (proven; exclude a ∆ where action is de minimis), both will be held liable (unless can demonstrate otherwise – onus of proof reversed onto ∆) o Point is to prevent wrongdoers from escaping liability by pointing to one another o A UK case has expanded Cook v Lewis to 3 tortfeasors o A California case (Sindell) held manufacturers liable proportionate to their market share where couldn’t trace to 1 Cannot simply opt for material contribution test over BFT (BM) o BM dissent suggests the notion of causation should be relaxed where unfair… Unfair that BFT would not hold police responsible even though breached duty to public b/c the “but for” in killing was the violence of the perpetrator (not the police failure to investigate the domestic dispute) Suggests relaxing causation where: 1. Breach of duty has occurred 2. Damage arose within the area of risk which brought the duty into being 3. Breach of duty materially increased the risk that damage of that type would occur 4. Practically impossible to establish that the breach caused the loss or not Page 5 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic Remoteness The defendant’s breach of duty must be a legal cause of the plaintiff’s injury. This should be understood to mean that the injury in question must not be too remote from the defendant’s negligent conduct. I.e. an interpretation of what is “reasonably foreseeable” - Not liable for unforeseeable consequences just b/c direct (Cameron – cow escaped, upstairs in house, through floor, flood) Liability depends on whether the damage was foreseeable by a reasonable person (The Wagon Mound No 1) o If did not know and could not be reasonably expected to know of risk >> not liable Sufficient that injury was reasonably foreseeable (even if occurred in unexpected way; magnified risk) (Hughes – kid burnt) With a dangerous activity, foreseeability should not be construed narrowly (Assiniboine School – snowmobile) o Test of foreseeability of damage here is a question of what’s possible rather than probable The Thin Skull Rule = as long as some injury to the plaintiff was foreseeable, the defendant is liable for all the consequences of the injury arising from the plaintiff’s unique physical or psychological make-up regardless of foreseeability (Bishop) Liable for injuries that are un-expectantly severe owing to a pre-existing condition; you must take your π as you find him Policy: consistent w/ desire to protect plaintiffs from interference and to fully compensate The Crumbling Skull Rule = if the plaintiff has a pre-existing condition, (in assessing damages) the defendant does not need to put the plaintiff in a position as though they do not have the condition (Athey) Don’t need to compensate for effects of the pre-existing condition which the π would have experienced anyways Novus Actus Interveniens (Intervening Act) Where there’s an intervening act that breaks the causal link >> no liability except when that second act is within the ambit of risk - - Stansbie: Harm brought about by the 3rd party (theft, in this case) was one that the ∆ (decorator) was supposed to guard against (given keys; supposed to lock up) >> found liable – the intervening actor (3rd party) did not break the causal link o ∆ undertook to protect a person from 3rd party intervention and was negligent Bradford (“gas!”): the more abnormal the chain of events, the more likely that the chain of causation has been broken o Majority – no liability; idiot yelling was an intentional intervening act; not within realm of foreseeability of grease build up fire (took all reasonable precautions against the fire / put it out) o Dissent – liability b/c normal that a fire (created by negligent grease fire) would induce a panic statement Manufacturers, Distributors, Contractors and Remoteness – 3rd parties involved May be liable even where another party made the damage worse (i.e. where chain of causation not broken) Smith v Inglis: It was reasonably foreseeable to the manufacturer that the 3 rd prong could be removed (i.e. by a 3rd party intervening actor), thereby exposing the π to risk of their negligence (cutting brought the manufacturer defect into effect) >> Not sufficient to break the chain of causation as 3rd party action was reasonably foreseeable >> manufacturer liable Good-Wear Treaders: obligation (to 3rd parties) to bar a sale if you know it will be used in an unsafe manner o Cannot escape liability to others w/ a warning to purchaser (though you will escape from liability to purchaser) o No obligation to find out use, but if you know intended use is dangerous >> obligation to bar sale o Policy: this encourages wilful blindness? o Purchaser ≠ sufficient intervening cause to sever chain of causation between the manufacturer/seller and the injured 3rd party. Accident would not have happened BUT FOR seller providing tires which were improperly used Defences Even if duty, breach, causation and proximate cause are established, π may still be defeated by a recognized defence. *Focus on π’s own conduct that may limit/exclude liability for their injury 1. Contributory Negligence – sharing of liability (partial defence) π is partly responsible Results in apportionment of damages between plaintiff and defendant(s) 2. Voluntary Assumption of Risk (volenti non fit injuria) (*interpreted very narrowly) – a complete defence Contributory negligence and comparative apportionment of blame is more often employed than 0/100 liability. Page 6 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic - Based on moral policy: no wrong is done to one who consents. There would have to be CLEAR indication that you are entirely waiving liability Must agree both to the risk of injury and waive the right to seek compensation from defendant (physical & legal risk) Risk must be obvious to the plaintiff and necessary part of the activity in question Plaintiff must be fully informed Application: Analysis of Voluntary Assumption of Risk (Crocker): ⇒ 1. Crocker participated voluntarily? No, intoxicated. He also did not assume legal risk through conduct. ⇒ 2. Crocker signed a waiver form? Crocker didn’t even know what he was signing. He may have assumed the physical risk, but definitely not the legal risk. 3. Illegality or Ex turpi causa (*rare) – a complete defence As a matter of public policy , denies a claim that would subvert the integrity of the legal system If you’re engaged in wrong doing (i.e. one bank robber fails to look after the other), court won’t stand in b/c they won’t work out responsibilities owed by people engaged in activities that the court will not condone. Defence only raised in extreme situations (when administration of justice would be brought into disrepute). Page 7 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic Liability for Failure to Provide Information Duty to Warn A. Duty to Warn – what will you be held responsible for / causality 1. Both a manufacturer of a product and a doctor may be under a duty to provide information to a consumer or a patient: in what circumstances? Sources: Hollis, (287) Reibl v. Hughes (297) Hollis - manufacturer duty to warn consumers about dangers in ordinary use of product (greater the danger, the clearer the warning must be), esp. w/ medical products; given knowledge imbalance; learned intermediary implications (*doctors)! Must clearly describe any specific dangers that could result; even where product not dangerous in and of itself, obligation to consider the limited knowledge/skills of the public Duty to warn about dangers possible w/ ordinary use (implies extraordinary use may not cause mfg liability) If a patient does not know all of the information cannot truly be said to give informed consent The greater the danger (or the more likely that there will be a problem w/ ordinary use or the more serious the potential harm), the clearer the warning has to be. Higher standard of care required w/ medical products (i.e. specificity of dangers) with medical products than other types of products b/c they involve ingestion or implantation (*close connection w/ body; serious consequences) >> Galloway: label warning is easy but court also says burden to provide information is a continuing obligation (may be very onerous to inform all consumers of a defect or danger of which there was no knowledge at the time of sale) Imbalance of power: in commercial situation, mfg of product has easy access to the info vs. consumer has no access >> Imbalance places heavy burden for mfg to explain dangers (also see: Childs on the commercial environment) Often it is not a huge burden for mfg to go into what the risks are (b/c it is easy >> onus to do this!) I.e. putting a label on product is quite an easy thing to do (remember Jordan House: no big deal to get a taxi) Reibl v Hughes - Duty of surgeon to disclose to the patient all material risks attending the surgery (seriousness of result + probability) 2. What does each have to do to fulfill the duty? Sources Hollis, (287) Reibl, (297) Videto (300) Van Mol (307) Note: Manufacturers, unlike doctors are not called upon to tailor their warnings to the needs and abilities of the individual patient and are not required to make the type of judgment call that is subject to scrutiny in informed consent actions Hollis: manufacturer may discharge duty to consumer if they properly inform a “learned intermediary” (the doctor) to give them the same level of knowledge; Doctor controls access to product (it is used under their supervision) The warning given to the learned intermediary must be sufficiently detailed. Fully apprise learned intermediary of all the risks. Policy: may be unrealistic for mfg to directly communicate w/ user (barriers of communication) Reibl: Duty of surgeon to disclose to the patient all material risks attending the surgery (seriousness of result + probability) - What is a material risk is a question of fact and for the Court to decide, not medical experts. Videto: 1. Don’t use ordinary practice with what doctors normally warn patients about; job is for trier of fact to make determination 2. Obligation to inform about special or unusual risks (i.e. severity not determinative; if potential consequence would be temporary whole-head hair loss–we may want to know about this unusual risk! *patient autonomy) 3. Don’t have to talk to the patient about subjective concerns, unless specifically raised by patient. Doctor must answer but not obliged to answer special concerns all the time (i.e. “please look after my baby finger because I’m a pianist!”). >> Subjective vs. objective concern?! 4. Nature and gravity of the procedure 5. General dangers inherent to operation need not be disclosed (i.e. “this is a scalpel”, dangers of anesthesia, infection rate (when does it become too general) 6. Language barriers?! (Videto) 7. Obligation to talk about alternative treatment (Van Mol case) 8. Therapeutic privilege – i.e. “they can’t handle the truth! They have an emotional or neurological deficit such that it would be medically improper to provide them with the thorough knowledge” = paternalism. Court says that if there is a genuine Page 8 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic therapeutic reason for non-disclosure, may accept that. BUT be careful about when this is relevant! How much did you tell? Could you have told more which they could’ve handled? *a subjective criteria (about specific person) (Videto) Van Mol: Doctor must effectively inform the patient of any real alternatives to a medical procedure (industry practice, and risks of each alternative). Also: if unhappy with Doctor’s choice, advise to get a second opinion 3. How do you determine that a failure to provide information has caused injury (a) in the case of a product, (b) in the case of medical treatment? Sources Hollis (313) Reibl (322) Hollis - A subjective test: π just has to show that they personally would not have consented had the risk been disclosed. Not an unfair burden on the manufacturer b/c they can easily discharge their duty by disclosing. Tougher for manufacturer than Dr. b/c manufacturer is expected to be more self-interested and a greater risk of minimizing the risk of their products. Deal with hindsight problem by court simply determining if the π is credible or not. Manufacturer cannot argue “no causality” to avoid liability if failed to inform learned intermediary of risks CAN’T say: “even if I informed intermediary, they wouldn’t have passed info forward (perhaps they had a tendency not to)!” nor “I didn’t have to connect w/ consumer; I could’ve contacted intermediary but didn’t” Normal causation rules don’t apply w/ intermediary (presence of intermediary does not excuse mfg liability) >> In learned intermediary cases, patient does not need to prove that the intermediary would have relayed the risks on the patient if the manufacturer had properly informed them. Reibl - When establishing causation in cases involving a failure to disclose medical risks, use a modified objective test: would a reasonable person in the patient’s shoes with all of the proper information have decided to have the surgery? Factors: o The urgency of the surgery (more likely to consent despite risk if urgent), o The possibility of waiting (if possible to wait until after some other event such as getting a pension, less likely to consent). o The gravity of the risk >> If no (they would have decided against surgery) causation is established >> If yes (they would’ve anyways), there is no causal link between doctor’s failure and the actual harm incurred Evidence provided by patient will always be self-serving >> DON’T ask “what would you have done HAD the doctor…” Rather, ask what a reasonable person would’ve done. 4. A doctor fails to warn a patient about a material risk. Patient has the operation and the risk materializes. Patient concedes that they probably would have had the operation even if they had been warned - but they would have delayed having it for a few months. Will the doctor be held liable for the injury? Is this fair? (If liable the doctor will be required to compensate the patient fully for the injury) Source Martin (330) Martin: o The π only needs to prove they would not have had the surgery at that particular time, NOT that they would never have had the surgery in the future. o No need to reduce damages to the “gap” to some hypothetical future date that the surgery would have happened. o NO temporal reduction of damages. o If the PTF would not have had that surgery at that time they are entitled to full recovery. Factors: o Surgery was ELECTIVE… not necessary to have. o Timing issue… clear future plans, made this clear to the Dr. Liability for Psychiatric Harm (Nervous Shock) 1. The consumer of a product discovers that it is dangerous. The danger does not materialize but the consumer suffers nervous shock. Should the manufacturer be held liable? Why? Mustapha (338): 2. Is the decision in Mustapha consistent with the Thin Skull Rule? 3. In what circumstances would you have a duty to respect the mental well-being of another person? Facts: Person saw dead flies in bottled water supplied by ∆. Claiming damages for developing a major depressive disorder Held: No liability for psychiatric harm in this case; π’s reaction was highly unusual, individual and particular to his history and culture. Wouldn’t have foreseeably harmed a person of ordinary fortitude. Page 9 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic For tort purposes, a psychological injury must be serious, prolonged, beyond negative emotions we accept in life (i.e. more than upset, anxiety, fear, etc.) (In Mustapha, he had a recognized psychiatric illness = demonstrated harm) Remoteness: Anxiety not a foreseeable consequence of defendant’s negligence; too unusual/extreme Must be reasonably foreseeable (“real risk”) that would occur to a reasonable person in the defendant’s circumstances (not something a reasonable person would dismiss as “far-fetched” Is it reasonably foreseeable that a person of ordinary fortitude would suffer a psychiatric injury? o No liability for exceptionally frail individuals o Not to be confused w/ thin skull rule (still applicable once harm is reasonably foreseeable); we are asking about the threshold to see if this type of harm was reasonably foreseeable AT ALL Once harm is reasonably foreseeable, the thin skull rule applies and the defendant is liable for all the arm even if it is unusually serious due to precondition (thin skull rule) o Exception: if ∆ knows of π’s sensitivities, they are considered: would a reasonable person, knowing of π’s sensitivities, reasonably foresee that their actions would cause the π psychiatric harm Exposed to unjustifiable risk of physical harm but the plaintiff only suffered psychiatric harm, liability is only found if a person of ordinary fortitude would have suffered harm. Liability for Pure Economic Loss 1. When will a person be held liable for economic losses suffered as a result of a negligent misrepresentation? Sources Hedley Byrne (351) Hercules Management (357, especially paragraphs 26-28, 31-41 and 43-50) - Undertaking + reliance (Hedley) - Reliance must be reasonable; disclaimer would work to negate liability (Hercules) 2. In Haskett and Wilhelm there is liability for economic loss even though there was no reasonable reliance? Why? Haskett: Wilheim: - Plaintiff was the subject of the misrepresentation (was not the one relying); - Linking the representation to the damage: “effective assumption of responsibility by representor” - Liability where assumed responsibility for a 3rd party’s interest (*overcomes privity) 3. A person who creates a dangerous product may be liable for the economic losses incurred by another person to negate the danger. In what circumstances? Sources: Winnipeg Condo (384, especially paras 3-6, 35-41 43-52) (PowerPoint): In Dorset Yacht – the reasonable foreseeability of economic losses does not give rise to liability by itself: in a competitive world we frequently can foresee a competitor suffering economic losses yet are not responsible for them. Under the Cooper framework, take reliance, representations and expectations into account Negligent Misrepresentation Hedley Byrne: If you undertake to provide accurate information to a person, the information is inaccurate and the person relies on its accuracy, you may be responsible for the economic losses incurred. If you provide info w/ disclaimer (as in Hedley), may not be liable If info is passed to someone else who relies, you may not be liable. (Not the case in Hedley but court foresees issue) Hedley Byrne test has 5 general requirements (affirmed in Queen v Cognos, cited in Haskett v Equifax) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Must be a DOC based on a “special relationship” btwn the representor and the representee Where info provided in business setting >> more likely to infer reasonable for person to rely and ∆ knows skill is being relied on: ∆ held to have accepted a relationship w/ inquirer. I.e. possesses a special skill in assistance of another VS. social setting Representation in question must be untrue, inaccurate, or misleading Representor must have acted negligently in making said misrepresentation Representee must have relied in a reasonable manner, on said negligent misrepresentation Reliance must have been detrimental to the representee in the sense that damages resulted Hercules: for a finding of liability, reliance must be reasonable (held: not liable b/c information was not intended for the purpose that led to the economic loss); disclaimer also works Held: Anns test still properly governs incidences of negligent misrepresentation (determining DOC) Page 10 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic There is a proximate relationship when a) ∆ ought reasonably to foresee reliance (in this case, accountants did not undertake responsibility to investors) b) Reliance would be reasonable (para 43 lists 5 indicia, where 4/5 will suffice): i. ∆ has a financial interest ii. ∆ is possessed of special skill iii. Advice provided in course of business iv. Not on a social occasion; and v. In response to a special inquiry (*would be clear factor indicating an undertaking) (a) & (b) >> Prima facie DOC Galloway: you have to make an undertaking to me – too many intermediaries will preclude undertaking; degree of proximity – don’t owe a duty to everyone because policy of indeterminate liability Preliminary questions required for the first part of the Ann’s test to get off the ground (i.e. to find a duty) Ask: 1. Did you rely? 2. Was that reliance reasonable? (*look to formality of the setting) Limits: It’s not every case of reasonable reliance that you’ll be liable Haskett: linking representation to the damage: “effective assumption of responsibility by representor” >> Third party: a representor can owe a duty to a claimant who has not actually relied on a misrepresentation but has suffered detrimental consequences from a third party’s reliance on that statement (i.e. subject of credit report) Proximate relationship exists when economic interests are at stake. Presumption that is reasonably foreseeable someone will rely on the info that you give in economic situations (presumed reliance) Negligent Misrepresentation and Negligent Provision of a Service Wilheim: (case where intended beneficiary doesn’t get benefit b/c lawyer screwed up) Liability where assumed responsibility for a 3rd party’s interest (*overcomes privity), rather than focus on reliance Policy: unjust to not allow beneficiaries to sue (doctrine of privity can be unjust at times) Negligent Supply of a Shoddy/Dangerous Product Winnipeg Condo: Where mfg negligently produces a dangerous product; consumer may discover defect before danger is realized (i.e. may be suing for purchase price back or to repair shoddy product << pure economic loss). When is there liability to negate the danger? Held: Yes, you can sue for costs of repair which are traced to the negligent builder (*particularly in housing situation) based in large on policy considerations Policy: builder would be liable when physical injury occurred – only fair to hold them liable for costs of preventing this harm Specific nature of housing (i.e. can’t just throw out a bad house like you can a laundry machine) Page 11 – Torts – Galloway – Condensed Final Outline 2014 – Kaitlyn Kastelic