Hamlet_Essay Sample - Mrs-Murray-Class-Wiki

advertisement

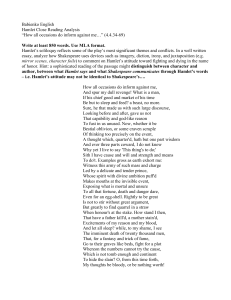

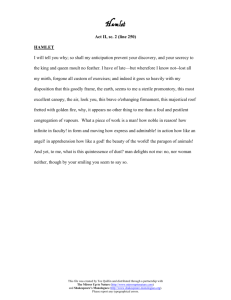

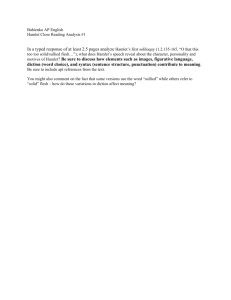

Student 1 Sample Student Murray English IV 29 March 2013 Psychological Effect on Sanity Literary analysts frequently describe Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” as an experiment, not only in regard to Shakespeare’s writing career, but referencing the life of Hamlet himself, partially due to his often-unprecedented actions. This gave rise to centuries of critical debate regarding both his sanity and the play’s overall direction. Critic Peter Strauss discusses these deliberations, saying, “What the play’s struggles amounted to when it was all said and done seem to elude one’s grasp” (Strauss). Strauss continues, describing a stylistic disconnect, which, “shifts from moment to moment, as an ongoing experiment, one that hardly resolves itself even by the end,” alleging that, “it is no wonder… T.S. Eliot described it as an artistic failure” (Strauss). However, the play conveys a surprising amount of insight. An examination of the underlying themes—namely sanity, rationality, the contrary, and their psychological relationship to corruption and revenge—in Hamlet integrally assists in understanding the piece’s overall direction. Furthermore, in a critical essay entitled, “Accommodating the Dead,” Michael Neill argues that, “Hamlet, like all revenge tragedies, embodies a fantasy of overcoming death, its perennially compelling power deriving from the idea that revenge can symbolically restore us to life by defeating the agency of our death, conveniently localized in a villain” (Neill). In the end, though, revenge destroys Hamlet. Over the course of five acts, one observes his Student 2 shift from enthusiastically attempting to right the wrongs of the world under the command of an aggressive, revenge-demanding ghost, to a hypocritically corrupt, morally humbled figure that lost both identity and life under the burden of an impossible task. Hamlet became the object of his own demise, leading many to question his sanity and rationality, as well as the two psychological components’ overall purpose. Despite an array of critical perceptions on this topic, Hamlet fails to constitute aimlessness, for the piece establishes the bold concept that worldly corruption destines its defeat. Even though Hamlet never went insane exactly, his thoughts shifted in the direction of madness because he used irrational behavior in an attempt to regain what went without restoration. In this way, he ultimately destroyed himself. Universally, insanity defines a mental illness that prevents a person from distinguishing between reality and perception, which often results in largely impulsive behavior (Howes). This slightly differs from irrationality, or the lack of consistently sound judgment. In “Hamlet,” the main character displays both insane and irrational tendencies, though not often simultaneously, thus lending to the viewpoint that his overall sanity remains intact. Examining Hamlet through a psychological perspective helps the audience better examine each character’s mindset. It also provides the most effective tools in investigating Hamlet’s level of sanity throughout the play. This becomes evident in Act I scene II, when Queen Gertrude and Claudius question Hamlet’s ‘prolonged and unmanly’ grief over the death of the former king. The queen attempts to appeal to Hamlet’s sense of logic, first reminding him that all people die eventually and later questioning why the Student 3 particular set of circumstances seemed so atypical to him. Hamlet defends his grief, saying, “These indeed “seem,” / for they are actions that a man might play. / But I have that within which passeth show, / these but the trappings and the suits of woe” (Shakespeare1.2.83-86). In this passage, Hamlet asserts that his sorrow goes beyond the devices used in false grief. In this section, he seems sane in his remorse over his father’s death and his mother’s hasty remarriage and apparent lack of grief. The ghost’s presence in the play gives rise to controversy, namely that Hamlet’s supernatural interactions exist as a testament to his level of sanity. Although one potentially dismisses the ghost itself as a figment of Hamlet’s imagination, the play opens with the guards’ discussion of its existence, where Horatio, a skeptical character, does not believe either of the other two watchmen who claim they’ve seen the king’s fully armored ghost wandering the courtyard. Though after seeing it for himself, Horatio says, “Before my God, I might not this believe / without the sensible and true avouch / of mine own eyes” (Shakespeare 1.1.54-56), thus validating its presence. After Hamlet speaks with the ghost, he decides to act insane in hopes of getting closer to King Claudius to avenge his father’s death and to appease his apparitional desires. As a result, through the remainder of the play, the audience only catches glimpses of a fully sane Hamlet. He begins breaking the rhythm of iambic pentameter and having largely out of character interactions with his former acquaintances. However, within these exchanges, Hamlet manages to portray several significant, completely sane insights to his listeners. He continues to understand the other character’s actions, particularly those that result from Claudius’ motives. For example, in Act II Scene I, Hamlet questions his childhood Student 4 friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, repeatedly asking them, “Were you not sent for? Is it your own / inclining? Is it a free visitation? Come, come, deal / justly with me. Come, come. Nay, speak” (Shakespeare 2.2.260-262).. In this passage, Hamlet’s repeated inquisition implies his awareness of the King’s investigation attempts. Hamlet’s sanity becomes even more evident when Act II closes with his selfbelittlement. He says, “This is most brave, / That I, the son of a dear father murdered, / Prompted to my revenge by heaven and hell, / Must, like a whore, unpack my heart with words” (Shakespeare 2.2.545-548). In this Act, Hamlet’s rationality, as well as his ability to recognize the negative effects of obtaining the truth with lies, overwhelmingly suggests his sanity remains intact. He continues to illustrate his remorse similarly when listing his shortcomings to Ophelia, admitting, “I am very proud, revengeful, ambitious, with more / offences at my beck than I have thoughts to put / them in, imagination to give them shape, or time / to act them in” (Shakespeare 3.1.125-128). Before their encounter, he delivers the most renowned soliloquy of the play. In saying, “To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer. The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing end them” (Act III Scene I, Line 5668), Hamlet discusses death in a way that critics often interpret as a contemplation of suicide. The controversial elucidation potentially evidences Hamlet’s insane tendencies, however, his actions appear to coincide with his rising plot in the remainder of the play. This stems the fact that Hamlet only discusses his desire to end his troubles and never alludes to ending his own life. Both of these aspects, along with his occasional tendency to revert back to speaking in iambic Student 5 pentameter—once in conversation with Ophelia and again when discussing his plan with Horatio—implies sanity. However, some of Hamlet’s behavior occasionally reveals potential psychopathy as well. In wishing suicide weren’t a sin—“he Everlasting had not fixed his canon 'gainst self-slaughter” (Shakespeare 1.2.132)—Hamlet suggests that Denmark, much like his life, compares to an unprofitable, weed-filled garden, thus divulging his occasional lapse into what appears to constitute lunacy. However, Dr. Sarah York further analyzed suicidal inpatient mental tendencies in “The Anatomy of Suicide,” ultimately suggesting that even though emotional and intellectual disturbances possess the capability to generate abnormal or insane conditions in the human mind, moral and emotional upheaval, “as a short lived condition exist separately from insanity” (York). Due both to his father’s death and the subsequent disarray in Denmark, Hamlet endured emotional and intellectual disturbances, both of which fueled his moral disjointedness, thus suggesting he wasn’t insane at all, but only emotionally conflicted. It’s interesting how Hamlet maintains his rationality when acting insane, yet occasionally disconnects from this rational state when he falls out of his act. In threatening to kill Marcellus and Horatio if they prevented him from following the ghost, Hamlet reveals irrationality penetrated his personality before he ever even decided to act upon it. In addition, he also dismisses his occasional rationality when following the king’s plans, first to depart for England, then to duel with Laertes. Hamlet’s hesitation exists clearly, and before agreeing to each request he says, “But thou wouldst not think how ill all’s here about my heart”(Shakespeare 5.2.99). Yet, Student 6 despite his uncertainty, Hamlet throws caution to the wind, and remains highly dependent on God saving him in times of mistake. However, his hastiness fails to constitute a lack of sanity; Hamlet’s mental state depended largely on the presence of sanity or rationality, either of which he consistently exhibited, thus making his sanity arguably present. Furthermore, similarly to Hamlet, many of the play’s characters display disjointedness in their rational and sane behaviors. For example, Polonius strives for status, and in his greed never achieves the worth he desires. Though no one regarded Polonius as insane, he characteristically adhered to the higher powers in his immediate presence, therefore demonstrating a quality that resulted in his conceivable irrationality at times. This becomes more and more evident when watching Polonius attempt to appeal to the person nearest him. For example, when discussing Hamlet with Gertrude and Claudius he says, “Take this from this if this be otherwise. / If circumstances lead me, I will find /Where truth is hid, though it were hid indeed / within the center” (Shakespeare 2.2.148-151). In this passage, Polonius senselessly gives the King and Queen permission to decapitate him if he provides incorrect information about Hamlet’s insanity. As Polonius’ foil, the courtier Osric arrives soon after his death, not only to illustrate the ever-present, irrational desire for the king’s favorability, but also the dispensability of such characters. When conversing with these men, Hamlet mimics their predilection for superfluous speech, creating a brief foil effect. When juxtaposed in this way, Hamlet appears highly rational in comparison, despite his feigned insanity. He posses the power both Osric and Polonius fiercely desire, but never seems overly concerned with Student 7 status roles, possibly due to his fascination with death. He regards the superficial very rationally, saying, “To what base uses we may return, Horatio. Why / may not imagination trace the noble dust of / Alexander till he find it stopping a bunghole” (Shakespeare 5.1.178-180). This indicates he recognizes that beggars and kings alike exist in fundamental equality. In this way, Hamlet’s mindset consistently remained above his companions, which made him appear as though he also operated above their mindlessly corruptive tactics. In the end though, corruption, ultimately leads to Hamlet’s demise. Throughout the play, Shakespeare follows a number of themes, each in some way attributing to Hamlet’s shift from moral to impulsive. For example, the contradictory relationship between corruption and honesty exists as reoccurring theme in the piece. The pertinence of this concept first becomes noticeable in the beginning of the second act, where in a conversation with Reynaldo, Polonius says, “Your bait of falsehood takes this carp of truth. And by indirections find directions out” (Shakespeare 2.1.63), thus introducing his theory of obtaining the truth through deception. This manipulation of words and, in turn, the truth, becomes an interesting reference point for later in Act II, when Hamlet says, “The play’s the thing wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king” (Shakespeare 2.1.566), thus indicating his use of a similar tactic to discover if Claudius really murdered his father. In the same act, Rosencrantz also told Hamlet, “the world’s grown honest” (Shakespeare 2.1.226), which introduced an interesting contradiction, because, despite Hamlet’s constant inquisition, neither Rosencrantz nor Guildenstern ever truthfully explained their visit. Hamlet later faces a similar encounter with Ophelia, where he prefaces his Student 8 interrogation, asking her, “Are you honest” (Shakespeare 3.1.105). In the same scene, he asks, “Where’s your father” (Shakespeare 3.1.131), and like Guildenstern and Rosencrantz, Ophelia dishonestly responds to Hamlet, and tells him that her father stayed at home. Throughout the play, the characters display a tendency to emphasize truth, yet unabashedly act in opposition, while Hamlet, despite his display of insanity, remains remorseful over his indirect attempts. This suggests that his behavior, though sane, became an irrationally hypocritical attempt to right the more evident wrongs of his immediate society. As the themes develop, Hamlet displays less and less remorse over his shortcomings. The effect of revenge on corruption most definitively accounts for Hamlet’s newfound limitations. In her analysis, Critic Camille Paglia confirms, “The ghost is a oppressive paternal presence. His aggressive demand for revenge is an energy-sapping burden that usurps Hamlet’s life and identity… and makes him a prisoner of the past” (Paglia). The kingdom became corrupt under the reign of Claudius, but in binding himself to Old King Hamlet’s ghost’s desire for revenge, Hamlet creates his own corruption, and single handedly destroys himself as a result. In discussing the reciprocal qualities of revenge, Francis Segar’s The School of Vertue, asserts, “If malice thee move to revenge thy call, dead almighty God, and danger of lames…contention and strife are the chief fruits of an evil life” (Segar). In this passage, Segar makes a more modernized claim against revenge, indicating that it results in little more than villainy. Evidenced by the deaths of Hamlet and Laertes, The School of Vertue, is useful in the interpretation of Shakespeare’s piece as a Student 9 statement against revenge, Although Hamlet appears to preserve his sanity to his death, he also manages to reach a certain acceptance to his surrounding world. Throughout the play, Hamlet used his own tactics, hoping to use revenge to justify the harsh realities of the world, or more specifically, the murder of Old King Hamlet. Laertes represents a foil character for Hamlet, which emphasizes both characters’ differences as much as their similarities. Laertes tends to take action, while the less morally ambivalent Hamlet takes the time to ensure the nature of his acts. However, as the play continues, Hamlet’s character begins to shift. This initially becomes noticeable in Act Five Scene Two when he tells Horatio, “Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well / when our deep plots do pall, and that should teach us. / There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, / rough-hew them how we will—“ (Shakespeare 5.2.10-12). In this passage, Hamlet suggests certain favorability lies with arbitrary actions as opposed to precisely planned arrangements. He also appears to rely on a higher power to guide him in the correct direction despite any failure that arises from impulsive action. In the same scene, he casually dismisses the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, saying, “They are not near my conscience. Their defeat does by their own insinuation grow” (Shakespeare 5.2.62). His dismissive justification of his betrayal and subsequent murder of his childhood friends indicates his transformation from a character floundering in selfrecrimination to a mechanism of the very evil he attempted to destroy. Paglia further explores this concept, writing “Hamlet takes the roles of detective and prosecutor, microscopically studying Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s ambiguities of response, forcing them along a track of self exposure until they are helpless” Student 10 (Paglia). As Hamlet becomes more and more distrustful, he fallibly dejects emotions and bonds of his former life. His moral ponderings of the previous scenes suggested that he felt above the dishonorable struggles occurring in Denmark. For example, in Act Two, he criticized Polonius for acting like a ‘fish monger,’ or using lies to obtain the truth (Shakespeare 2.2.168). He continues to regard the King’s actions as dishonorable in the beginning of Act 5 when he tells Horatio, “Does it not, think thee, stand me now upon—He that hath killed my king and whored my mother, popped in between th' election and my hopes, thrown out his angle for my proper life” (Shakespeare 5.1.70). However, Hamlet feigned madness, betrayed Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, committed three unprovoked murders, as well as led Ophelia to her death, altogether demonstrating that Hamlet failed to act above dishonor, instead managing to get swept into it. In attempting to right the wrongs of the corrupt king, Hamlet created his own irreversible corruption and his own sense of harsh reality. Additionally, of the four deaths in the final scene, only half were preconceived, an indication of both the consequences of arbitrary actions and the unpredictability of death itself. At the end, Hamlet, potentially still haunted by the ghost’s final words ‘Remember me,” uses his dying words both to forgive Laertes and to request that Horatio tells his story. He says, “Had I but time (as this fell sergeant, Death, / is strict in his arrest), O, I could tell you /—But let it be. —Horatio, I am dead” (5.2.330-333). In death, he accepts and ascertains the restrictions of both human action and judgment. Hamlet’s irrational attempts to restore Denmark to its initial state, not his mental inhibitions, ultimately led to his destruction. Student 11 In the end, even centuries after its publication, “Hamlet” continues to inspire debate. Though considered a directionless failure by some, it impudently addresses revenge and its subsequent effect on psychological competence. Despite Hamlet’s altruistic interpretations that rivaled superficiality and all of his futile attempts to reverse worldly corruption, he hypocritically became yet another instance of the misfortune he tried to prevent. As the final act concludes with an empty stage, Shakespeare leaves his audience with a harsh depiction of irreversible and corruptive devastation. Though Hamlet never loses his sanity, he instead instigates his own corruption, due both to conflictions of deceit and the absence of an alternative for the unadulterated world he wished to reinstate. Student 12 Works Cited F, S., and Robert Crowley. "Against Anger, Envy, and Malice (2)." The School of Vertue And Book of Good Nurture; Teaching Children and Youth Their Duties. Newly Perused, Corrected and Amended. Hereunto Is Added a Briefe Declaration of the Duties of Each Degree Also Certain Prayers and Graces, Compiled by R.C. London: Printed for M.W. and George Conyers, at the Sign of the Golden-Ring upon Ludgate-Hill, over against the Old Baily, 1687. N. pag. Print. Howes, Ryan. "Psychotherapy: Perseverance vs. Preservation." Psychology Today. Heathprofs.org, 27 July 2009. Web. 14 Mar. 2013. Neill, Michael. "Accommodating the Dead: Hamlet and the Ends of Revenge." Issues of Death, Mortality, and Identity in English Renaissance Tragedy. Oxford Scholarship Online, 1997. Web. 21 Apr. 2013. Paglia, Camille. “Stay, illusion’: Ambiguity in Hamlet.” Ambiguity in the Western Mind. Ed. Craig J. N. De Paulo,Patrick Messina, and Marc Stier. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. 117-130. Rpt. in Shakespearean Criticism. Vol. 111. Detroit: Gale, 2008. Literature Resource Center. Web. 19 Apr. 2012. Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. The Bedford Introduction to Literature. 8th ed. NY: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2008. 1589-686. Print. Strauss, Peter. "Hamlet: an experiment without an outcome?" Shakespeare in Southern Africa 14 (2002): 27. Literature Resource Center. Web. 30 May 2011. York, Sarah. "Suicide, Lunacy and the Asylum in Nineteenth-Century England." University of Birmingham Research Archive. University of Birmingham, Dec. 2009. Web. 21 Apr. 2013.