Kings_and_Beggars_HAMLETHAMLETHAMLET[1]. - Mrs

advertisement

![Kings_and_Beggars_HAMLETHAMLETHAMLET[1]. - Mrs](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009516748_1-3844b9165fd03c733da149dac4941f43-768x994.png)

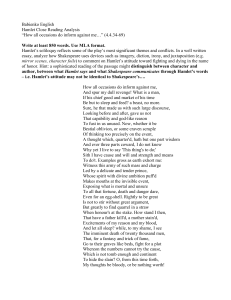

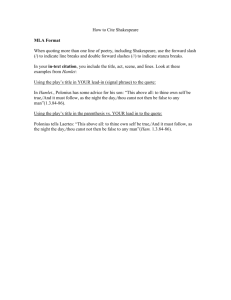

Sample Student English IV Mrs. Murray 5-31-12 Kings and Beggars: Hamlet and the Roots of Modern Egalitarian Thought The storm of media attention that the wedding of Kate Middleton, a ‘commoner’, and Prince William gathered recently is a testament to the scrutiny that the British people places on the affairs of kings. This vigorous attention isn’t new; English kings and queens have been in the public eye as long as the crown has existed, but public criticism of monarchs without reprimand would have been unheard of before the birth of the modern era (Paglia). Until the modern era, the judgment of a monarch was considered to be direct from god, under a strict hierarchical philosophy known as the “Great Chain of Being” (Fludd). Railing against the “Great Chain of Being” in the vein of modern thought, Hamlet by William Shakespeare revealed structural social and political problems with England’s system of governance during a tumultuous reformation of popular philosophy. Much like the scrutiny that modern leaders undergo, the bulk of Shakespeare’s message on politics regards how leaders should make decisions and the necessity for honesty. In Hamlet Shakespeare characterizes several leaders or potential leaders who behave in similar ways, each character having a characteristic or flaw that differentiates him from the next, and through this motif, shows his view of each flaw or virtue. Hamlet, the protagonist of the play, is devoted to righteousness and effectiveness of his tactics, planning at length, even to a fault to outwit his malicious adversaries with words instead of actions and preserve the honor of the state of Denmark. Claudius, the antagonist of the play, also schemes behind closed doors, but only for personal gain and is prone to violence, killing his brother and marrying his widow to become king. Old king Hamlet appears to his son in the play as a ghost, urging him to seek violent revenge for his murder, and in life, King Hamlet won territory from old King Fortinbras of Norway in a questionable physical quarrel (Tiffany). Finally, young Prince Fortinbras of Norway gathers a rogue army during the play and begins to fight publicly for the betterment of Norway. The close characterization of the characters in the ruling class is used by Shakespeare to reveal his image of an ideal leader. The method by which Shakespeare judges the honor and righteousness of the actions of these characters is by their fates, alive or dead. The fate of old King Hamlet was to suffer in purgatory for sins that he committed in his lifetime, but the only real knowledge that the reader has of King Hamlet’s actions is of his duel with King Fortinbras of Norway over a disputed territory. If this brash action is enough in Shakespeare’s eyes to put someone in a symbolic purgatory, although King Hamlet was not deceptive in his ruling, then Shakespeare was condemning the prideful, violent, thoughtless action of monarch, private or public. Shakespeare thought that a monarch should always know the impact of his actions on his people and act to protect their interests. Young Hamlet acted in a nearly diametric manner from Old Hamlet; he rarely acted without morality in mind, but he conducted much of his schemes in a clandestine manner. Young Hamlet, at the end of the play dies, suggesting that honesty and transparency in action was just as momentous a virtue in Shakespeare’s view as acting with the good of the people in mind. Claudius is the pure example of an improper leader in Hamlet, both conducting perfidious, violent plots, and rarely acting with the good of anyone but himself in mind, and in the end is undone by his own plotting when Hamlet forces Claudius to drink from the poisoned goblet intended for him. Claudius’s death at the hands of Hamlet further paints social and governmental progression in England through the death of a dishonorable tyrant at the hands of a much less malicious man. Unlike all of the other potential leaders of Denmark, Prince Fortinbras solely lives to take the throne, and the reason for this is his governmental philosophy. Fortinbras, unlike Prince Hamlet, actually goes to war for the rectification of wrongs, over acquisition of the land wrongfully lost by his father, but unlike old King Hamlet, he gathers an army from his home country, which is symbolic of gathering the will of the people. Instead of for vainglory, Fortinbras fights for the good of the Norwegian people. Fortinbras’s rightful actions constitute Shakespeare’s picture of what a monarch should be, an honest and dedicated public servant. Through some vicious criticism over class distinctions and heavy general public scrutiny, the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton is widely accepted. Divergence from the “Great Chain of Being” hasn’t always been accepted, however. We can trace this breaking of social bonds to early modern philosophies, and notably, William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Shakespeare’s play shows social equality through repeated emphasis of the universality of human possibility and through the tragic portrayal of the feminist power structure in his writing. Shakespeare felt that the worth of two different people was always, universally the same, regardless of their positions in life. In a conversation with the avaricious and power hungry Polonius, Prince Hamlet plays at this notion of universal equality when he mistakes the noble for a fish salesman,” ’Do you know me, my lord?’’Excellent well. You are a fishmonger.’ ’Not I, my lord’ ‘Then I would you were so honest a man.’”(2.2.174-77). In extolling the virtues of a fishmonger as greater than a noble, Shakespeare rejects the traditional value system of the “Great Chain of Being” and places value upon an individual’s integrity. In another conversation with Polonius, who, through his constant devotion to his socioeconomic betterment, is a symbol of the class-valuing old order, Prince Hamlet shows the variability in the interpretation of the shape of a cloud, ” ‘Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in the shape of a camel?’ ‘By th’ mass, and ‘tis like a camel indeed.’ ‘Methinks it is like a weasel.’ ‘It is backed like a weasel.’ ‘Or like a whale’ ‘Very like a whale’ ” (3.2.347-52). This cloud that can be interpreted as many different animals is analogous to the worth of the individual in Shakespeare’s purview. The infinite range of possibility for individual development suggested by the cloud flies in the face of a rigid class structure and favors individual rights at an unprecedented level for the time in England. Shoring up his commentary, Shakespeare notes the democratic elements of death in a scene where Hamlet reveals the location of Polonius’s body, “a man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm” (4.3.28-9) the notion that a king might pass through a peasant implies both that kings will ultimately serve the peasants, and that there is nothing heavenly to keep a king above a beggar. Ultimately, Shakespeare found no logic in the archaic precept of divine right to rule. In addition to general celebration of the individual, Hamlet emphasized the feminine struggle in the early modern world. In regards to the gender commentary in Hamlet, the literary concept of vampirism is essential. Vampirism in literature is signified generally by an older figure representing corruption and outworn values, sustaining itself through the destruction or exploitation of a younger figure, generally a female (Foster 19). In Hamlet the two main female characters are consumed by the plotting of the figures representing the old order, namely Polonius and Claudius. In the play, Ophelia and Hamlet are engaged in a love affair that the male members of Ophelia’s family do not allow because of class distinctions. Later on in the plot, Ophelia is used as a bait to flush out the reason for Hamlet’s insanity, and while she is doing the bidding of the old order, Hamlet becomes privy to her father’s scheme against him and instructs Ophelia to,” Let the doors be shut upon him, that he may play the fool nowhere but in ‘s own house”(3.1.133-34) Ophelia is driven to insanity after any chance of her relationship with Prince Hamlet is destroyed and when her father dies because of another plot against Prince Hamlet. Gertrude is killed when she drinks from a poisoned goblet that was intended for Hamlet, and some of her last words serve to cement the denial of freedom that Shakespeare commented on through the play. When told not to drink from the cup by Claudius, she remarks, “I will, my lord. I pray you, pardon me. (drinks)” (5.2.287) her resistance to male domination was met with death, and the tragic depiction of these destructions of women’s rights are a large part of Shakespeare’s thesis against rigid social order. Kate Middleton and Prince William, in getting married, may have stirred up mild controversy, but they owe the possibility of their union to the first modern individualist English philosophers. Without them, love would have had no place in their lives. Moreover, there would be no free forum for the controversy of the people if modern philosophy had never taken hold. One of the first great works of the modern era, Hamlet attacks the rigidity of the past in favor of a celebration of the inherent worth of everyone and a call for accountability in leaders. Works Cited Fludd, Robert. Urtriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet Et Minoris Metaphysica, Physica Atque Technica Historia, in Duo Volumnia Secundum Cosmi Differntiam Diuisa. Digital image. Folger Shakespeare Library. Folger Shakespeare Library. Web. 21 May 2012. <http://www.folger.edu/eduPrimSrcDtl.cfm?psid=147>. Foster, Thomas C. How to Read Literature like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading between the Lines. New York: Harper, 2003. Print. Paglia, Camille. "'Stay, illusion': Ambiguity in Hamlet." Ambiguity in the Western Mind. Ed. Craig J. N. De Paulo, Patrick Messina, and Marc Stier. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. 117-130. Rpt. in Shakespearean Criticism. Vol. 111. Detroit: Gale, 2008. Literature Resource Center. Web. 21 May 2012. Shakespeare, William. Hamlet: William Shakespeare. New York: Spark Pub., 2002. Print. Tiffany, Grace. "Hamlet, reconciliation, and the just state." Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature 58.2 (2005): 111+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 21 May 2012.